Continuing Education Activity

Ultrasound is a critical noninvasive diagnostic modality for the detailed evaluation of the female pelvis. This modality allows ready and portable imaging of the uterus, ovaries, and other structures at a reasonable cost without ionizing radiation or contrast. The absence of radiation is important since the ovaries are particularly sensitive to radiation.

Pelvic ultrasound plays a critical role in diagnosing conditions such as ovarian cysts, fibroids, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancies, as well as monitoring pregnancy and guiding procedures. An essential tool for evaluating reproductive and gynecologic health, this imaging modality ensures accurate diagnoses and facilitates the effective management of many conditions. This activity outlines the technique, indications, and contraindications for the procedure. This activity also highlights the role of the interprofessional team in enhancing the care of patients undergoing pelvic ultrasound.

Objectives:

Identify the indications for a pelvic ultrasound.

Apply the techniques involved in performing a pelvic ultrasound, differentiating between transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound approaches based on clinical indications.

Assess the clinical significance of pelvic ultrasound.

Select interprofessional team strategies for enhancing care coordination and communication to advance the use of pelvic ultrasound and improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Ultrasound is a key modality for the evaluation of the contents of the female pelvis. It allows ready and portable imaging of the uterus, ovaries, and other structures at a reasonable cost and without ionizing radiation. Lack of irradiation is important since the ovary is particularly sensitive to radiation in young patients and those of reproductive age.[1]

Pelvic ultrasound is performed via the transabdominal or transvaginal approach.[2] A gel is placed on the skin above the bladder, allowing transducer contact without intervening air on the skin surface. A urine-filled bladder helps lift small bowel superiorly out of the pelvis, creating an optimal acoustic window and preventing bowel air from refracting or degrading the ultrasound beam.[3] The ultrasound traverses the pelvis unimpeded through bladder fluid, insonating pelvic contents and returning to the transducer to be processed by the machine.

Images are obtained in the midline sagittal plane and parasagittal planes angled to the periphery of each hemipelvis. Similarly, transverse plane images are obtained by angling superiorly and inferiorly from a mid-bladder position. Real-time ultrasound allows the transducer to obtain the best anatomic images with subtle angling, even if the structures are not in perfect longitudinal or transverse plane alignment.[4] The uterus is typically located in the midline, and the ovaries and adnexa are usually found lateral to the uterus. However, just as a uterus may not be midline, the position of the ovaries is somewhat variable, possibly in the low, mid, or upper pelvis. They may also be seen in the midline, superior to the uterus.

Anatomy and Physiology

Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the female pelvis is essential for accurate pelvic ultrasound interpretation, as it enables clinicians to identify normal and abnormal structures. Key components such as the uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and surrounding tissues must be carefully evaluated to ensure proper diagnosis and management of gynecologic and obstetric conditions. Although limited, pelvic ultrasound may also be utilized for some male indications.

Uterus/Cervix

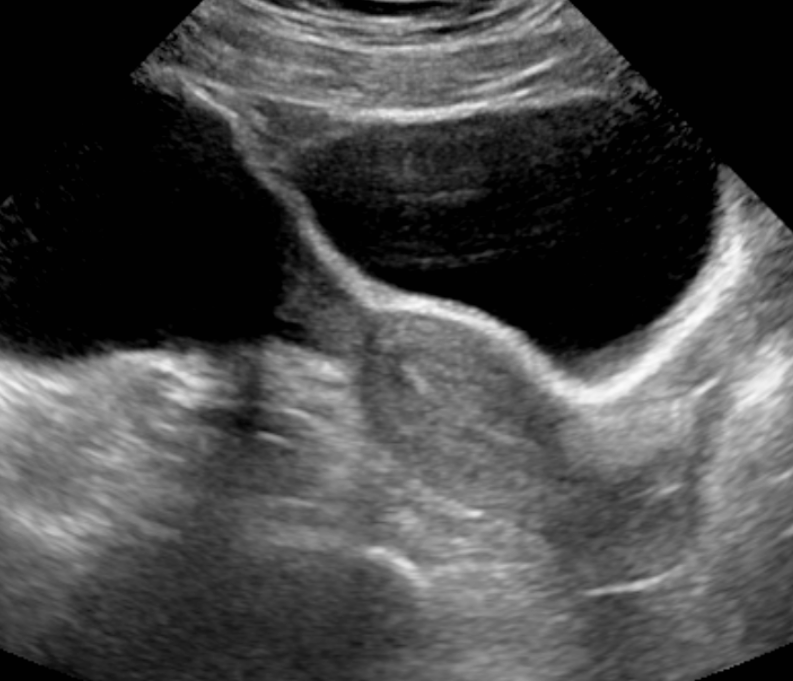

The midline and parasagittal views are utilized to demonstrate the uterus from the fundus to the cervix. The addition of transverse views allows for a complete assessment of size and contour, and the anatomy can be evaluated for abnormalities such as masses, typically benign leiomyomas. The uterine endometrial cavity may show contents of variable echogenicity if obstructed (eg, from cervical stenosis in an older woman status post radiotherapy or a child with hematometrocolpos). Otherwise, the uterine walls are covered, and the endometrial lining is visualized with a different echogenicity than the rest of the uterus, which often varies by hormone levels, patient age, and time in the menstrual cycle.[5] Classically, the endometrial lining is echogenic with a trilaminar morphology in the first half of the menstrual cycle or proliferative phase. The lining is homogeneously echogenic in the cycle’s second half (secretory phase). The thickness of the endometrial lining in a postmenopausal patient should not measure >5 mm (unless treated with tamoxifen). Endometrial myomas, endometrial polyps or other masses may account for a prominent endometrial cavity, particularly in postmenopausal patients with unexplained bleeding.[6][7] Ultrasound can help assess the endometrial contents via fluid injected through the cervix, a methodology known as sonohysterography performed with transvaginal sonography (TVS).

Ovaries

The adnexa includes the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and associated vasculature and soft tissue support structures. The ovaries appear almond-shaped, typically lateral to the uterus and anterior to the internal iliac vasculature. Ovarian morphology, including the presence and number of contained follicles/cysts, varies with age, endocrine function, and time in the menstrual cycle. Knowledge of normal volumes for various ages is important when evaluating a patient for ovarian torsion.[8] Torsed ovaries can enlarge to 3 to 4 times the normal ovarian volume. The contralateral ovary allows for size comparison. Pelvic inflammatory disease may enlarge both ovaries, but usually to a far less extent than the unilateral enlargement seen in ovarian torsion. TVS allows for better analysis of adnexal mass morphology by utilizing higher ultrasound frequencies.[9]

Adnexa/Other Structures

Fallopian tubes may appear as dilated fluid-filled tubes (hydrosalpinx) due to obstruction, usually as a sequela of chronic infection. Unusually, a fallopian tube may torse without concomitant ovarian torsion.[10] A complex adnexal cyst or mass may be indicative of an ectopic pregnancy. Pelvic ultrasound can assess other structures within the pelvis.[11] Hernias in the inguinal region or into the labia or canal of Nuck may be seen.[12] Free fluid can also be demonstrated in the abdomen and pelvis. Triangular echoless areas, particularly in the posterior cul de sac, may be due to ascites or be physiologic fluid. Fluid with heterogeneous echogenicity or septation suggests a more complex component, such as hemorrhage, infection, or proteinaceous fluid. Various other pathologies, including appendicitis, diverticulitis, and gastrointestinal malignancy, such as appendiceal mucoceles, can also be visualized at times.[13]

Male Pelvis

Ultrasound use for the male pelvis is limited. The presence of free abdominal fluid can be assessed. Undescended testes in the groin and hernias can be seen using high-frequency linear array transducers. Magnetic resonance imaging is supplanting transrectal sonography (TRS) for the evaluation of the prostate and seminal vesicles. Transabdominal sonography (TAS) can allow visualization of the dilated urethra in posterior urethral valves, and occasionally, a valve itself can be seen in real-time. Inferiorly angled midline views are most helpful. Transperineal sonography (TPS) can also be utilized to diagnose posterior urethral valves, assess pelvic floor muscles, and guide prostate biopsy.[14][15]

Indications

The main indications for pelvic ultrasound are as follows:

- Diagnostic examination of the female pelvic organs, including the uterus, ovaries, and adnexal structures.

- Obstetric evaluations Early pregnancy diagnosis and dating, fetal anatomy, placental location, and amniotic fluid assessments are routinely performed. Pelvic ultrasound is the ideal imaging technique for pregnant women as it does not entail using contrast or x-rays.[16] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Obstetric Ultrasound," for more information.

- Masses palpated on physical examination Some commonly palpated masses include large ovarian tumors, congenital abnormalities of uterine shape (often noted in pregnancy), and uterine fibroids.

- Pelvic pain Often, the diagnoses of pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancy, and normal pregnancy are made with the help of pelvic ultrasound. Less often, during pelvic ultrasound, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or diverticulitis is diagnosed. Please see StatPearls companion resources, "Ectopic Pregnancy, Ultrasound," and "Pregnancy Ultrasound Evaluation," for more information.

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding Possible pregnancy, known pregnancy, menses, precocious puberty, and postmenopausal bleeding can be evaluated.

- Evaluation for appropriate positioning of an intrauterine device.[17]

- Evaluation for polycystic ovarian syndrome and infertility.[18] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Sonography Gynecology Infertility Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation," for more information.

- Diagnosis or assessment of ascites or other free fluid. Guidance in performing procedures, including amniocentesis, needle biopsies, and aspiration of free fluid.

- Evaluation of the prostate and seminal vesicles in the male patient The prostate, particularly when looking for malignancy, is best assessed with a transrectal probe.[19]

Contraindications

Pelvic ultrasound is generally a safe and noninvasive procedure, but some contraindications must be considered. In cases of severe pelvic infections, recent pelvic surgery with open wounds, or active vaginal bleeding, ultrasound may need to be deferred or carefully evaluated by the healthcare provider to avoid complications or inaccurate imaging. TVS may be relatively contraindicated in late pregnancy or in high-risk patients (ie, patients with premature rupture of membranes or placenta previa).

Equipment

Pelvic ultrasound requires specific equipment to ensure high-quality imaging. This includes a portable or stationary ultrasound machine with a high-frequency transducer, gel for proper contact between the transducer and skin, and a monitor for real-time image visualization. Lower frequencies allow better penetration. Higher frequencies allow better near-field resolution. Transabdominal probes are typically lower in frequency than transvaginal probes. In TAS, a full bladder may be necessary to optimize image quality, while TVS uses a specialized probe for closer examination of pelvic structures.

Personnel

The personnel involved in pelvic ultrasound typically include sonographers trained in performing the imaging and physicians, such as obstetricians, gynecologists, or radiologists, who interpret the results. Advanced practitioners, such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants, may also assist in patient preparation and follow-up care, ensuring a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and management.

Preparation

Preparation for performing a pelvic ultrasound involves several important steps to ensure accurate imaging and patient comfort. For TAS, patients are typically instructed to drink water before the procedure to fill the bladder. This helps lift the bowel out of the pelvic area and creates a clearer acoustic window for better visualization. For TVS, the bladder is usually emptied before the procedure, and the patient is advised to lie in a lithotomy position. The sonographer or clinician applies a gel to the abdomen or vaginal probe to facilitate smooth contact and the transmission of sound waves. Patients are also informed about the procedure, including any potential discomfort, to ensure they feel comfortable and relaxed during the examination.

Technique or Treatment

Pelvic ultrasound utilizes various techniques to obtain high-quality images of the pelvic organs, with the choice of approach depending on the clinical indication. In addition to TAS and TVS, other methods like 3D imaging and Doppler ultrasound are also employed to assess blood flow and enhance visualization of complex pelvic structures.

Transabdominal

The transabdominal technique typically consists of midline sagittal and parasagittal images angled from the midline to the periphery of both hemipelves. Transverse plane images start at the midline overlying the bladder and angle superiorly and inferiorly to image the pelvis. If there is limited fluid within the bladder, especially in young children, the transducer can be placed over the lateral aspect of the bladder and directed to the contralateral side for imaging. This technique helps provide a larger amount of fluid for the ultrasound beam to traverse and a better working acoustic window.

Transvaginal

Transvaginal scans use elongated transducers with higher frequency elements in the range of 7 MHz to 8 MHz compared to those used for routine transabdominal imaging (around 3.5 MHz). The transducer is placed into the mid to upper vagina (covered by a condom) to obtain coronal and sagittal views that allow for high-resolution imaging of the uterus and its contents, helpful in obstetrical imaging as well as the analysis of the ovaries and adnexa. With its introduction in the late 1980s, TVS revolutionized the evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. The higher frequency transvaginal transducer can be used, and there is no need to traverse a fluid-filled bladder or fat on the anterior abdominal wall.

Other Techniques

Postprocessing software is available for many ultrasound machines, which allows 3-dimensional reconstruction of typical greyscale ultrasound images to create surface and volumetric images. This method has been used to reconstruct the vagina, cervix, and uterus for evaluation of müllerian duct system anomalies.

At times, the vagina and uterus may be evaluated by TPS with the placement of a transducer on the labia in the longitudinal or transverse plane. This alternative has allowed the analysis of vaginal obstructions, especially in virginal patients. The technique has also been used for placenta previa analysis when the use of an intravaginal probe is deferred.

Doppler

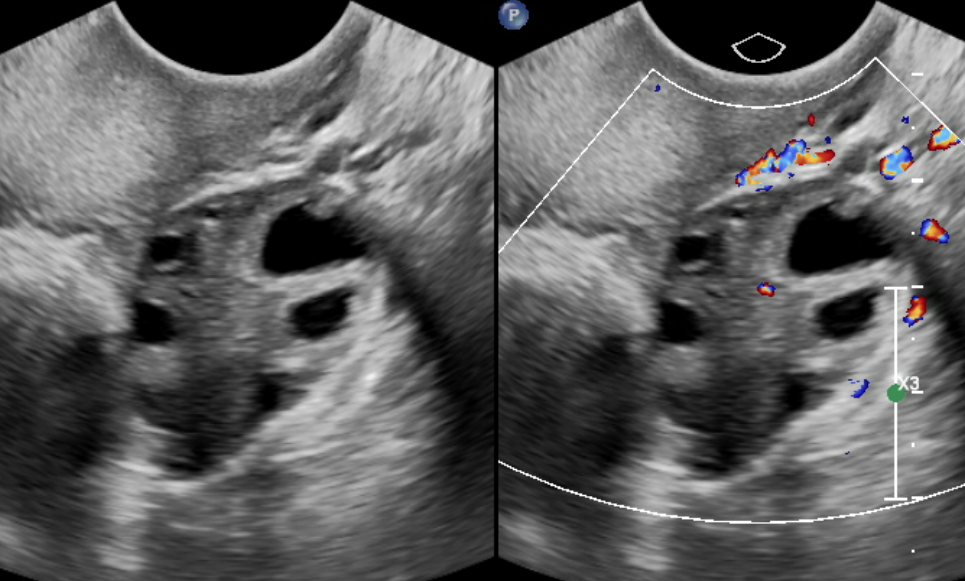

Whether routine color Doppler or power Doppler imaging is used, cystic structures can be analyzed for their degree of vascularity. Color Doppler readily displays iliac vessel flow, often in a plane posterior to the ovaries. Spectral Doppler can be utilized to evaluate vessels for abnormalities in venous or arterial flow signals. Pseudoaneurysms, although not typical in the pelvis compared to the groin, might display the typical neck of the lesion with a yin-yang color flow pattern. When evaluating the presence or degree of vascular flow, power Doppler can also be utilized in situations where color Doppler may be suboptimal (very low or slow flow).

Color Doppler can reveal dilated or clotted gonadal veins and can also be used to demonstrate vascular flow to the ovary. However, due to the dual blood supply of the ovary and the known findings of peripheral and central vascular flow in surgically proven torsed ovaries, the usefulness of color Doppler is limited. The greyscale morphologic findings of the ovary for the diagnosis of torsion are more sensitive than the flow-related findings seen with color Doppler. For the evaluation of testicular torsion, color Doppler is diagnostic.[20]

Complications

Pelvic ultrasound is generally considered a safe procedure with minimal risks. However, complications can occasionally arise, particularly with TVS. These may include mild discomfort or pressure during the insertion of the probe, especially in patients with pelvic sensitivity. In rare cases, infection may occur if proper hygiene protocols are not followed. Additionally, if the procedure is performed in patients with certain conditions, such as active vaginal bleeding or recent pelvic surgery, the risk of complications may be increased, requiring careful consideration and potential deferral of the procedure.

Clinical Significance

Extensive clinically significant information is discovered when imaging the pelvis with ultrasound. These results include information about the uterus, its shape, size, and characteristics of the endometrial cavity and its contents. Identification and evaluation of ovarian size and morphology help determine if there are any abnormalities in the ovary for a given age. Ultrasound can identify masses in structures other than the uterus and ovaries, such as adnexal cysts. Ovarian neoplasms can be assessed for size, morphology, and growth over time. Ovarian teratomas with their usual cystic and solid (Rokitansky nodule) contents, including bone or calcium, can be visualized. Rectal contents can be evaluated, especially in neonates or young children. Thick bowel walls of chronic inflammation or tumor may be noted at times. Urethral cysts may be seen, particularly in adult females. Rarely, an abnormality of the bony pelvis may also be noted.[21][22][23]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective utilization of pelvic ultrasound in patient care requires a collaborative approach, with each healthcare professional bringing their expertise to enhance diagnostic accuracy, optimize outcomes, and ensure comprehensive, patient-centered care. Physicians are responsible for interpreting results, diagnosing, and providing appropriate referrals or treatments. Advanced practitioners, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, support the assessment and follow-up care of patients, ensuring continuity. Nurses provide patient education and support during procedures, while pharmacists may assist with managing medications related to diagnostic or therapeutic interventions.

Physicians, sonographers, nurses, and other health professionals must collaborate and communicate ultrasound results in real-time, allowing for timely interventions and care adjustments. Routine discussions and case reviews foster mutual understanding and improve patient care delivery. A comprehensive strategy to improve outcomes includes implementing standardized protocols for ultrasound imaging, training clinicians across specialties, and integrating ultrasound results into clinical decision-making. Collaborating with a multidisciplinary team ensures that all aspects of the patient’s care are addressed, from diagnostics to follow-up and treatment plans. By coordinating care across specialties, patient safety is maximized, and the quality of care is improved.