Introduction

The anal canal is the terminal part of the gastrointestinal tract that conveys material from the rectum to the anus. While it is typically around 2.5 to 4 cm in length, it is more complex than it seems. The anal canal plays a vital role as a defense against organisms that might enter the body, it differentiates between solid, liquid, and gas, and it contributes to fecal continence. Often not evaluated in the absence of symptoms, pathologies of the anal canal may be treated with wide-ranging measures as conservative as a sitz bath to as significant as surgical resection or radiation.

Structure and Function

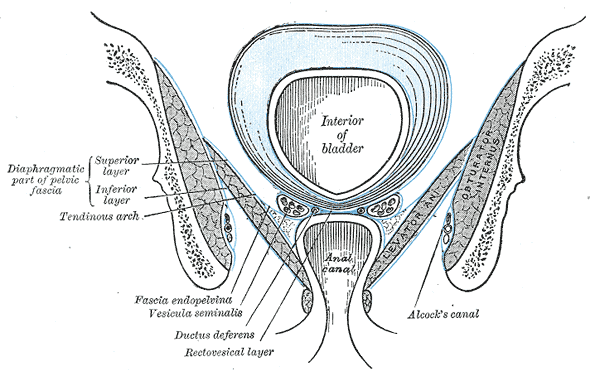

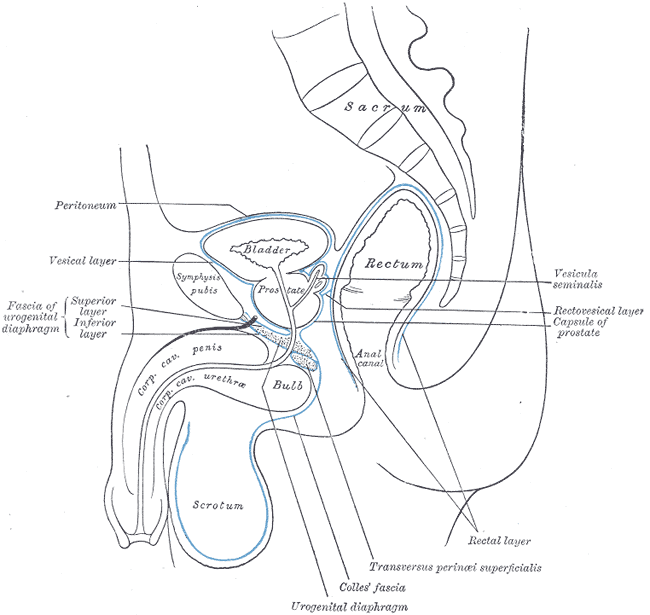

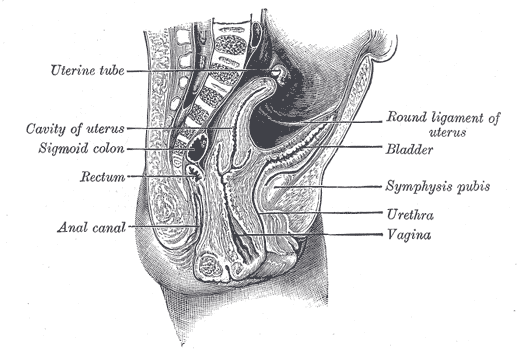

The anal canal serves as a channel connecting the rectum to the end of the gastrointestinal system, the anus. It is located within the anal triangle of the perineum and in between the fat-filled and wedge-shaped ischioanal, or ischiorectal, fossae that accommodate its expansion for the passage of fecal material. The transition from the rectum to the anus can be identified by the anorectal junction, or anorectal ring, which appears as a bend in the gastrointestinal tract and is supported by the puborectalis muscular sling. The anorectal junction is also the site where muscular fibers of its two sphincters blend superiorly with those of the puborectalis muscle.

The two functionally and anatomically distinct sphincters surrounding the anal canal are the internal anal sphincter and the external anal sphincter.[1][2] The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is involuntary. Its function is dependent on the integrity of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR), which involves the reflexive relaxation of the internal anal sphincter in the presence of rectal distension. It maintains a resting pressure in the absence of rectal distension. Thus, the internal anal sphincter's resting pressure is widely used as a direct measure of its functionality and is often assessed when evaluating a variety of pathologies. The external anal sphincter (EAS) is under voluntary control. The external anal sphincter maintains its tone to keep the orifice of the anal canal closed and relaxes upon defecation. While the rectoanal inhibitory reflex causes the internal anal sphincter to relax in the presence of rectal distension, the external anal sphincter works to keep stool in the anal canal until one is ready to defecate.

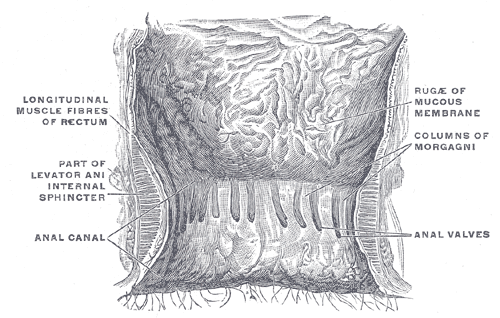

The anal canal is typically divided into superior and inferior segments by the pectinate, or dentate, line. The pectinate line is a visible zig-zagging line formed from the inferior aspect of longitudinal folds known as the anal columns or anal valves. The pectinate line demarcates the superior two-thirds of the anal canal from the inferior one-third. It also serves as an embryologic landmark that explains the differing arterial supply, venous drainage, lymphatic drainage, and nervous supply of the segments of the anal canal.

Embryology

As with its structure and function, the embryology of the anal canal differs superior and inferior to the pectinate line. Above the pectinate line, the anal canal is the terminal portion of the hindgut and is endodermally derived. As with the rest of the hindgut, the superior anal canal is lined by columnar epithelium. Below the pectinate line, the anal canal is ectodermally derived and is lined with stratified squamous epithelium.

At birth, the external anal sphincter is not yet fully developed or under complete voluntary control. An individual usually achieves voluntary control of the external anal sphincter near the ages of 18 to 24 months.[3][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

An excellent approach to understanding the arterial supply, venous drainage, and lymphatics of the anal canal is to consider the supply above and below the pectinate line and the area of overlap.[5]

Arterial Supply and Lymphatic Drainage

Above the pectinate line, the anal canal is supplied by terminal branches of the superior rectal artery, a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. Lymphatic fluid from this region is conveyed to the inferior mesenteric lymph nodes.

Below the pectinate line, the anal canal is served by the middle and inferior rectal arteries. The middle rectal artery is a branch of the internal iliac artery, while the inferior rectal artery is a branch of the internal pudendal artery that arises from the internal iliac artery. The lymphatic drainage below the pectinate line is primarily to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Venous Drainage

The venous drainage of the anal canal superior to the pectinate line is to the superior rectal veins, which drain into the inferior mesenteric vein. These veins are part of the hepatic portal venous system, conveying oxygen-poor, nutrient-rich blood to the liver for processing. The venous drainage of the anal canal below the pectinate line is to the internal pudendal veins, which convey their contents to the internal iliac vein. These veins are part of the systemic venous system that transports oxygen-poor, nutrient-poor blood to the heart. Anastomoses of the portal and systemic venous systems within the anorectal canal allow for potential collateral circulatory routes. In patients with portal hypertension, anorectal varices may be apparent. Not unique to the anal canal, these portosystemic anastomoses are also present elsewhere in the body.[6]

Nerves

Similar to the blood supply and lymphatics, it is also useful to discuss the nervous system of the anal canal from the perspective superior and inferior to the pectinate line. These two regions are distinctly innervated and respond to different stimuli. [7]

Above the pectinate line, the anal canal receives autonomic innervation from the inferior hypogastric plexus. The parasympathetic innervation inhibits the tone of the internal anal sphincter and evokes a peristaltic contraction to allow defecation. Sympathetic innervation works in opposition to maintain the tone of the internal anal sphincter and preserve continence. Given viscerosensory signals return from this region, the superior aspect of the anal canal is most sensitive to stretch or distention.

Below the pectinate line, the anal canal receives somatic innervation derived from branches of the pudendal nerve. As a result, the inferior aspect of the anal canal is highly sensitive to pain, temperature, and touch.

Physiologic Variants

Little anatomic variation of the anal canal exists in the literature. Multiple case reports have discussed anal canal duplication in which a neonate is born with an extra anal canal, either superior or posterior to the main canal. Individuals with a duplicated anal canal tend to have a fairly typical accessory anal canal; however, it ends in a blind pouch with no connection to the rectum. Currently, this condition is treated with surgical excision to avoid the accessory anal canal acting as a potential nidus of inflammation, fistulization, or malignancy.[8]

There is some variation of the anal canal that relates to aging. The internal anal sphincter increases in thickness as individuals age. The effect is usually more pronounced in females over 50. Current guidelines consider maximal internal anal sphincter thickness greater than 4 mm as abnormal in patients under 50 years of age and 5 mm in those over 50 years of age. This becomes important when identifying patients with hypertrophy of the internal anal sphincter.[9]

Surgical Considerations

During surgery involving the anal canal, the surgeon has a variety of techniques available to identify the transition between the upper portion and lower portion of the anal canal. Identifying the region of the pectinate line is vital to understanding the vascular supply and drainage and innervation of the segments of the anal canal for surgical considerations.

The tight space and compact anatomy of the anal canal contribute to a difficult compartment for surgical procedures. For instance, the anatomy of the anal canal makes sphincter-saving surgery during cases of lower rectal cancer very challenging. These surgeries have the potential for negative outcomes, such as anal sphincter compromise with incontinence or permanent colostomy. Given the limited window available for surgeons within the anal canal, other approaches have been explored, such as transvaginal, transperineal, trans-sacral, and abdominal.[10]

Clinical Significance

Incontinence

The anal canal and its muscles maintain fecal continence; consequently, any failure of the anal canal musculature may result in fecal incontinence. The current guideline for patients with fecal incontinence is to suggest anal manometry to assess sphincter tone. Positive manometry revealing a dysfunction of sphincter tone is usually followed by anorectal imaging to evaluate structural integrity.[11]

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are a common anal disorder that involves the engorgement and potential prolapse of veins in the lower part of the anus and rectum. A variety of factors predispose individuals to develop hemorrhoids, such as pregnancy, age, diarrhea, chronic constipation, sitting for too long (especially on the toilet), heavy lifting, anal intercourse, obesity, and genetics.

There are two main types of hemorrhoids: internal hemorrhoids and external hemorrhoids. Internal hemorrhoids are deep within the anal canal, superior to the pectinate line, and are usually painless because of the visceral sensations from that region. These hemorrhoids often present with painless bleeding and, upon straining, may prolapse out of the anus. External hemorrhoids exist below the pectinate line and are in close proximity to the anal opening. Given that external hemorrhoids occur in the inferior anal canal, served by somatosensory signals, they are often painful and itchy.

Hemorrhoids often resolve spontaneously, but patients may relieve the discomfort using dietary fiber, stool softeners, and daily sitz baths. It is also important to advise these patients about adequate fiber intake, decreased straining in the washroom, and decreased time spent sitting on the toilet. Large or bothersome hemorrhoids may be treated with banding or surgical hemorrhoidectomy in the office.[12][13]

Anal Cancer

Anal cancer is a disease in which the normal cells of the anus become malignant. Most cases are related to the human papillomavirus virus (HPV). Factors that enhance the risk of anal cancer include smoking and immunodeficiency. The prognosis of anal cancer is mostly dependent on the size of the tumor and whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes. Following the identification of anal cancer, it is staged from 0 to 5 based on size and spread, with stage 5 carrying the worst prognosis. Treatment of anal cancer often includes surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or some combination of these methods.[14]