Introduction

Appropriate patient position can facilitate proper physiologic function during pathophysiologic processes and access to certain anatomical locations during surgical procedures. Multiple factors should be considered when choosing the patient's position. These factors include patient age, weight, size, and past medical history, including respiratory or circulatory disorders.

Structure and Function

The most common patient positions with common indications and concerns include the following.

Supine Position

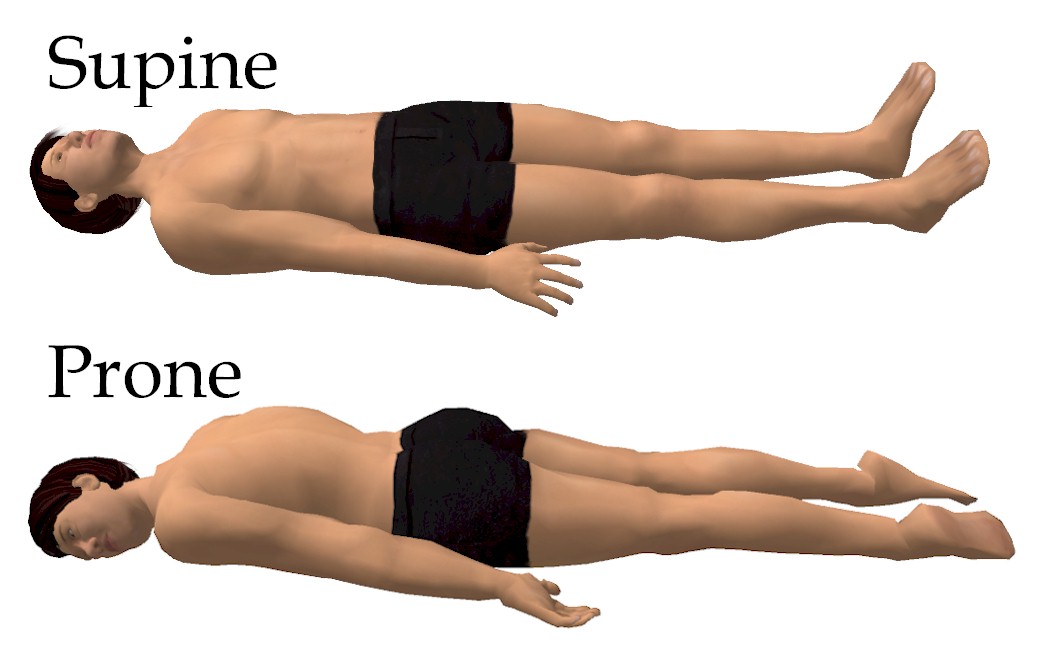

This is the most common position for surgery with a patient lying on his or her back with head, neck, and spine in neutral positioning and arms either adducted alongside the patient or abducted to less than 90 degrees. Arm abduction maintained under 90 degrees prevents undue pressure of the humerus on the axilla, thereby preventing brachial plexus injury. Arm adduction with hands and forearms maintained in a neutral position with palms facing the body or supinated decreases external pressure on the ulnar nerve and prevents injury. A “draw sheet” that passes under the body and over the arm before tucking under the torso can hold the arm in proper position against the body. See Image. Supine and Prone Positions.

Supine Position Variations

Lawnchair position: A variation of supine in which the hips and knees are slightly flexed and above the level of the heart relieves pressure on the back, hips, and knees, facilitates venous drainage from the lower extremities, and reduces tension on the abdominal musculature

Frog-leg position: This variation of supine in which the hips and knees are flexed and externally rotated facilitates access to the perineum, groin, rectum, and inner thigh. However, the knees must be supported to avoid stress and dislocation of the hips.

Trendelenburg position: A variation of supine in which the head of the bed is tilted down such that the pubic symphysis is the highest point of the trunk facilitates venous return and improves exposure during abdominal and laparoscopic surgeries. Hemodynamic changes, including increased venous return and cardiac output, are temporary, with most hemodynamic variables returning to baseline within ten minutes. Respiratory changes, including upward displacement of the abdominal contents into the diaphragm, decrease functional residual capacity and respiratory compliance, requiring higher airway pressures to maintain ventilation. Gravitational changes from prolonged head-down positioning can increase intracranial pressure, intraocular pressure, and swelling of the face, larynx, and tongue, increasing the risk for postoperative airway obstruction. Sliding and shifting of a patient in Trendelenburg positioning are often prevented with shoulder braces. However, caution must be used to prevent undue pressure, potentially resulting in compression or stretch injury to the brachial plexus.

Reverse Trendelenburg position: This variation of supine in which the head of the bed is tilted upward so that the head is the highest point of the trunk facilitates upper abdominal surgery. Hemodynamic changes include decreased venous return, which can result in hypotension. Gravitational changes, in concert with hemodynamic changes, can result in decreased cerebral perfusion, and invasive arterial monitoring should be considered. Sliding and shifting a patient in reverse Trendelenburg positioning can increase pressure over the posterior calcaneus.

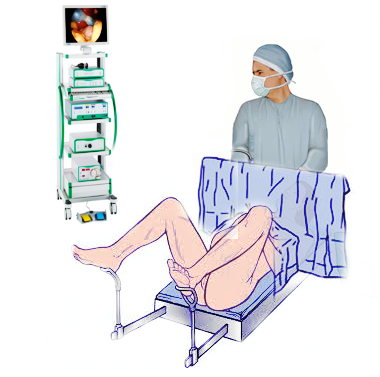

Lithotomy Position

Commonly used during gynecologic, rectal, and urologic surgeries with a patient lying supine with legs abducted 30 to 45 degrees from midline with knees flexed and legs held supported with the foot of the bed lowered or removed to facilitate the procedure (see Image. Lithotomy Position). Legs are raised and lowered in concert to prevent spinal torsion and muscular injury. Prolonged procedure time increases the risk for lower extremity compartment syndrome secondary to inadequate perfusion; recommendations include periodically lowering the extremities throughout prolonged procedures. Lower extremity padding prevents nerve compression against leg supports; common peroneal nerve injury is most common as the peroneal nerve wraps around the head of the fibula, which rests against leg supports. Hemodynamic changes include increased venous return and transient preload and cardiac output increases. Respiratory changes result from cephalad displacement of abdominal contents, which decreases lung compliance, functional residual capacity, and tidal volume.

Lateral Decubitus Position

Commonly used during surgery requiring access to the thorax, retroperitoneum, or hip with a patient lying on the nonoperative side and carefully positioning the extremities. The lower extremities are carefully padded between the knees and below the dependent knee to avoid excessive external pressure over bony prominences. The dependent lower extremity is somewhat flexed to avoid stretching or compressing the lower extremity nerves. The upper extremities are placed in front of the patient, with neither arm abducted more than 90 degrees to prevent brachial plexus injury; an axillary roll should be placed below the axilla to prevent compression of the brachial plexus and axillary vascular structures. The dependent upper extremity is flexed at the shoulder, slightly flexed at the elbow, and secured on a padded arm board with padding under bony prominences; invasive arterial monitoring should be placed in the dependent arm to detect compression of the axillary vascular structures better. The non-dependent upper extremity is flexed at the shoulder and slightly flexed at the elbow. It is often secured with a suspended armrest, with care not to abduct the arm more than 90 degrees and to pad the bony prominences. The head and neck are maintained in a neutral position to prevent lateral rotation and stretch injury to the brachial plexus; care must be given to avoid folding or rolling the dependent ear or undue external pressure on the dependent eye. Respiratory changes from the lateral weight of the mediastinum and cephalad displacement of abdominal contents result in decreased pulmonary compliance, and lateral decubitus positioning favors ventilation of the nondependent lung. See Image. Lateral Decubitus Position.

Prone Position

Commonly used during surgery requiring access to the posterior fossa of the skull, posterior spine, buttocks or perirectal area, or lower extremities with the patient lying on his or her front with head, neck, and spine maintained in a neutral position; the patient is turned from supine to prone while maintaining the neutral position of the head, neck, and spine. The risk of monitors and tube dislodging can be minimized by disconnecting as many monitors, lines, and catheters as possible before turning the patient; temporary disconnection of the ventilator from the endotracheal tube prevents dislodgement. Many commercially available headrests and pillows are designed to support the forehead and malar regions with openings for the eyes, nose, and chin, preventing external pressure on these structures; special caution must be taken to avoid undue pressure on the eyes as perioperative vision loss is an avoidable complication of the prone position. Respiratory changes result in alveolar recruitment and increased oxygenation without affecting cardiac output. Therefore, it is a useful maneuver in severely hypoxemic patients with early acute respiratory distress syndrome. See Image. Supine and Prone Positions.

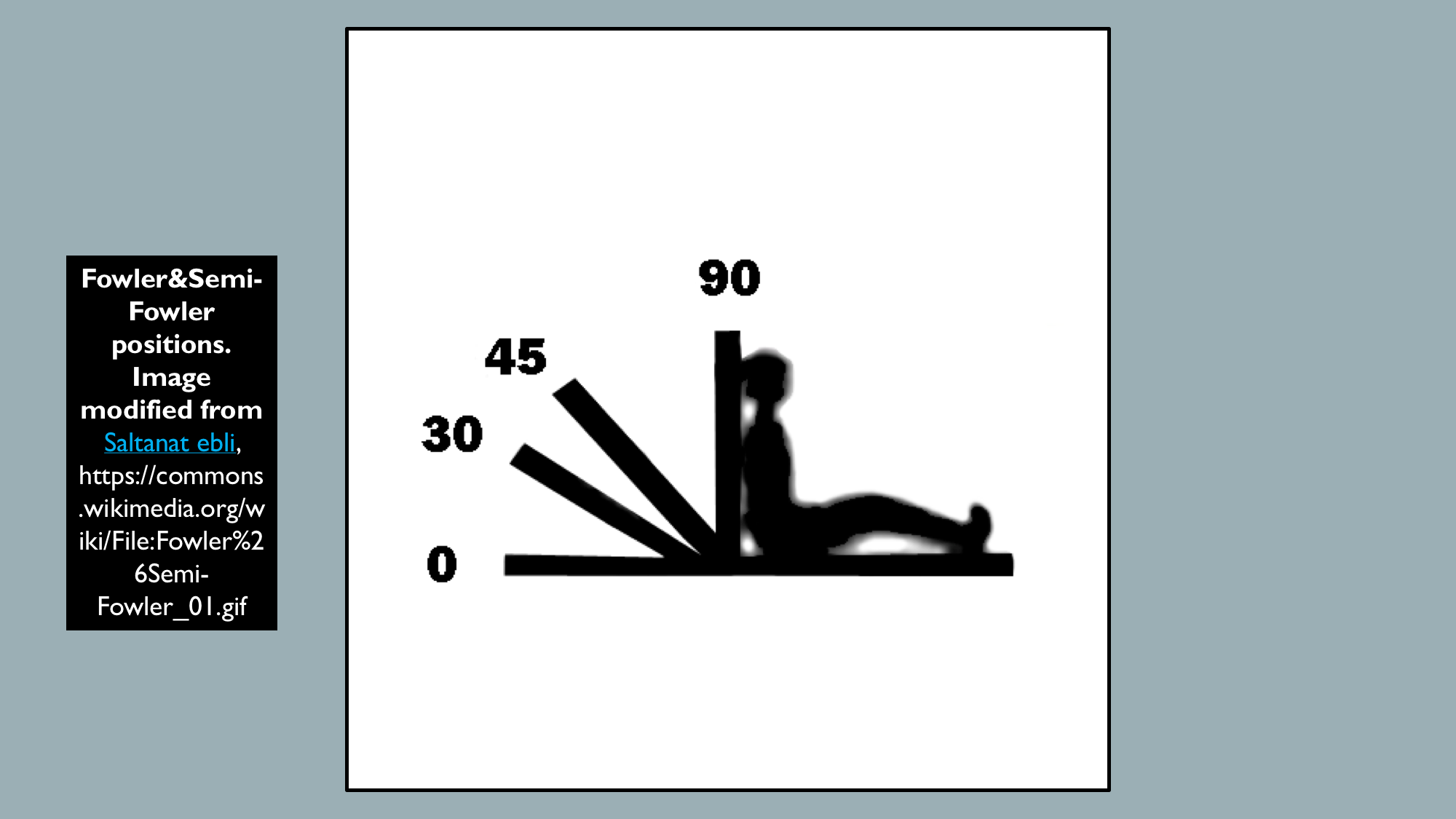

Fowler's Position

This is the most common position for a patient resting comfortably, whether in an inpatient or in the emergency department: knees either straight or slightly bent and the head of the bed between 45 and 60 degrees (See illustration, Fowler and Semi-Fowler Positions). Respiratory changes result in increased oxygenation by maximizing chest expansion, minimizing abdominal muscular tension, and minimizing the effects of gravity on the chest wall; therefore, they are useful maneuvers for patients with mild to moderate respiratory distress. High Fowler's position with the head of the bed between 60 and 90 degrees is useful during placement of orogastric and nasogastric tubes as it decreases the risk of aspiration.[1][2][3][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Lower extremity compartment syndrome is a rare but serious complication of the lithotomy position resulting from inadequate perfusion of the lower extremity. The resulting tissue ischemia, edema, and muscle breakdown increase facial compartmental pressure. Recommendations include periodically lowering patients' legs in lithotomy position during prolonged procedures to promote perfusion.

Nerves

Nerves are most commonly injured during surgical procedures secondary to external compression or stretch. The most commonly injured nerve is the ulnar nerve from malpositioning of the upper extremity in the supine position. Ensure that the arm is supinated or in the neutral position to avoid ulnar nerve compression and abducted no more than 90 degrees from the body to prevent stretch injury to the brachial plexus.[5][6][7][8] Lower extremity nerve injuries are less common, though precautions can still be taken. Common peroneal nerve compression can result from direct compression over the fibular head in the lithotomy position; ensure proper padding between bony prominences and supports. Sciatic nerve stretch can result from flexion at the hip in the lithotomy position; take care when positioning the patient to move the lower extremities in concert with one another and prevent hyperflexion at the hip.[9][10]

Muscles

Muscle strain is a less common side effect of patient positioning but can result from the patient’s inability to react to the movement of the extremities. Take care, especially with the lower extremities, to move simultaneously to avoid muscle and joint injury.

Surgical Considerations

Compression and damage to underlying nervous and vascular structures are significant considerations for patient positioning, especially during prolonged surgical procedures. Common surgical positions and frequently associated complications can be found above. Providers should ensure that all bony prominences and foreign bodies held against the patient are appropriately padded to avoid undue pressure on the skin and soft tissues.

Clinical Significance

Proper patient positioning can facilitate access to anatomical locations during surgical procedures and promote appropriate physiologic function during pathologic states, such as the Trendelenburg position, to increase the venous return in a hypovolemic patient. Care to position the patient properly both facilitates procedural aims and aids in preventing subsequent complications.