Continuing Education Activity

Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled structures that may be simple or complex. They are common findings usually discovered incidentally on physical examination or imaging. Ovarian cysts can cause complications, including rupture, hemorrhage, and torsion, which are considered gynecological emergencies. Therefore, it is essential to promptly diagnose and treat them to avoid high morbidity and mortality. This article reviews the evaluation, treatment, and complications of ovarian cysts and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of the different types of ovarian cysts.

- Outline the typical presentation and most common physical exam findings for patients presenting with ovarian cysts.

- Review the criteria for conservative versus surgical management of ovarian cysts.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and highlight the interprofessional team's role in evaluating and treating patients affected by life-threatening complications of ovarian cysts.

Introduction

The adnexa is a set of structures adjacent to the uterus, consisting of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Even though the fallopian tubes are one of the major adnexal structures, this article will focus on the ovaries and the different types of cysts that can form within the ovary. The ovaries are suspended laterally to the uterus via the utero-ovarian ligament, covered by the mesovarium, which is one of the three components of the broad ligament, and connected to the pelvic sidewall via the infundibulopelvic ligament, which is also known as the suspensory ligament of the ovary. The blood supply to the ovaries comes directly from the ovarian artery, a direct branch of the aorta. The venous drainage is unique as the right ovarian vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava, whereas the left renal vein drains the left ovarian vein. In premenopausal women, the ovaries produce numerous follicles a month, with one dominant follicle maturing and undergoing ovulation.

As a result of ovulation, a fluid-filled sac known as an ovarian cyst can form on one or both ovaries. Adnexal masses or ovarian cysts are not uncommon, with 20% of women developing at least one pelvic mass in their lifetime. Various subcategories have characterized more than thirty types of ovarian masses, and management is determined by the characteristics of the lesion, the age of the patient, and the risk factors for malignancy. In women of reproductive age, most ovarian cysts are functional and benign and do not require surgical intervention. However, ovarian cysts can lead to complications such as pelvic pain, cyst rupture, blood loss, and ovarian torsion that require prompt management.[1]

Etiology

The etiology of ovarian cysts or adnexal masses ranges from physiologically normal (follicular or luteal cysts) to ovarian malignancy.[2] Ovarian cysts can occur at any age but are more common in reproductive years and increase in menarchal females due to endogenous hormone production.[3] Simple cysts are the most likely to occur in all age groups, and mixed cystic and solid and completely solid ovarian lesions have a higher rate of malignancy than simple cysts. Although most ovarian cysts are benign, age is the most important independent risk factor, and post-menopausal women with any type of cyst should have proper follow-up and treatment due to a higher risk for malignancy.[4][5]

Risk factors for ovarian cyst formation include

- Infertility treatment- Patients treated with gonadotropins or other ovulation induction agents may develop cysts as part of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.[2]

- Tamoxifen. [3]

- Pregnancy- In pregnancy, ovarian cysts may form in the second trimester when hCG levels peak.[6]

- Hypothyroidism[7]

- Maternal gonadotropins- The transplacental effects of maternal gonadotropins may lead to the development of fetal ovarian cysts.[8]

- Cigarette smoking[9]

- Tubal ligation- Functional cysts have been associated with tubal ligation sterilizations.[10]

Epidemiology

The actual prevalence of ovarian cysts is unknown, as many patients are believed to be asymptomatic and undiagnosed, and the prevalence depends on the population studied. Approximately 4% of women will be admitted to the hospital for ovarian cysts by age 65. In a random sample of 335 asymptomatic 24 to 40-year-old women, the prevalence of an adnexal lesion was 7.8%.[11] Another study that examined ovarian cysts in postmenopausal women showed a prevalence of 2.5% for a simple unilocular adnexal cyst.[12] In a survey of 33,739 premenopausal and postmenopausal women, 46.7% had an adnexal cyst on transvaginal ultrasound, with 63.2% showing resolution of the abnormality on subsequent ultrasounds.[13][14]

In postmenopausal women, 18% can develop one or more Graffian follicles, which appear as cysts on imaging.[11][15][16] Most of these cysts are benign. Mature cystic teratomas or dermoids represent more than 10% of all ovarian neoplasms. Ovarian cysts are the most common tumor in infants and fetuses, with more than 30% prevalence.[17] In the United States, ovarian carcinomas are diagnosed in more than 21000 women annually, causing 14,600 deaths.

Pathophysiology

During the normal menstrual cycle, the follicular phase is characterized by increasing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) production. That leads to the selection of dominant follicles for priming to release from the ovary. In a normal functioning ovary, estrogen production from the dominant follicle leads to a luteinizing hormone surge (LH), resulting in ovulation. After ovulation, follicular remnants form a corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. This inhibits FSH and LH production. If pregnancy does not occur, the progesterone declines, FSH and LH rise, and the next cycle begins.

Functional Cysts

Follicular and Corpus Luteal Cysts

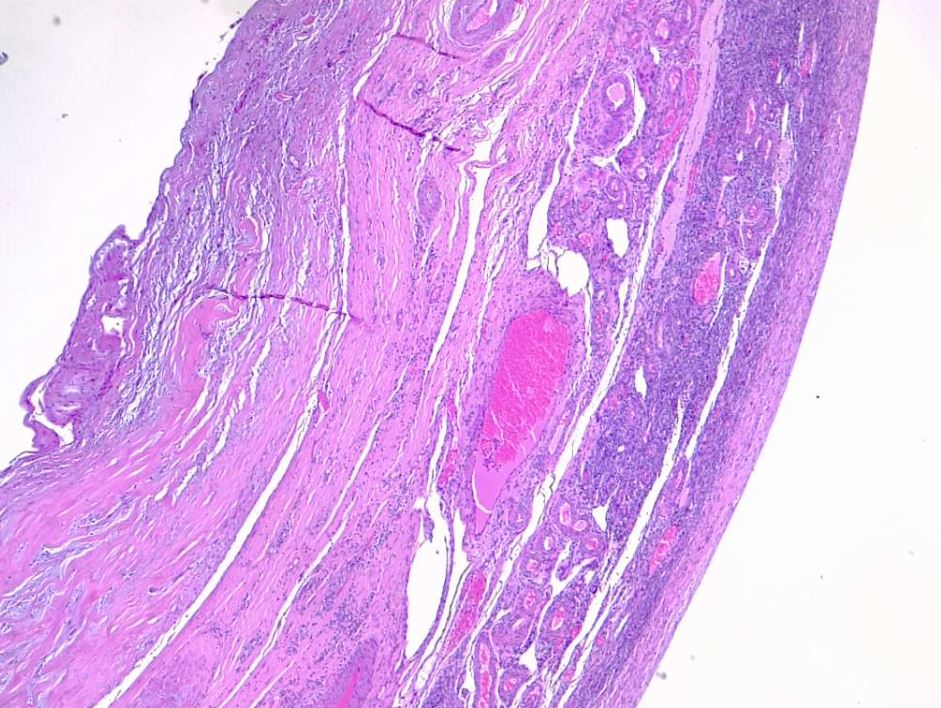

Follicular and corpus luteal cysts are considered functional or physiologic cysts, and both occur during the normal menstrual cycle. Follicular cysts arise when follicles fail to rupture during ovulation and can appear smooth, thin-walled, and unilocular. In the follicular phase, follicular cysts may form because of a lack of physiological release of the ovum due to excessive FSH stimulation or the absence of the usual LH surge at mid-cycle just before ovulation. These cysts continue to grow because of hormonal stimulation. Follicular cysts are usually larger than 2.5 cm in diameter. Granulosa cells lead to excess estradiol production, which in turn leads to decreased frequency of menstruation.

Without pregnancy, the life span of the corpus luteum is 14 days. If the egg is fertilized, the corpus luteum continues to secrete progesterone until its dissolution at 14 weeks, when the cysts undergo central hemorrhage. If the dissolution of the corpus luteum does not occur, it may result in a corpus luteal cyst, which usually grows to 3cm. Corpus luteal cysts can appear complex or simple, thick-walled, or contain internal debris. Corpus luteum cysts are always present during pregnancy and usually resolve by the end of the first trimester. Both follicular and corpus luteal cysts can turn into hemorrhagic cysts. They are generally asymptomatic and spontaneously resolve without treatment.[18]

Theca Lutein Cysts

Theca lutein cysts are luteinized follicle cysts that form as a result of overstimulation in elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels. They can occur in pregnant women, women with gestational trophoblastic disease, multiple gestation, and ovarian hyperstimulation.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

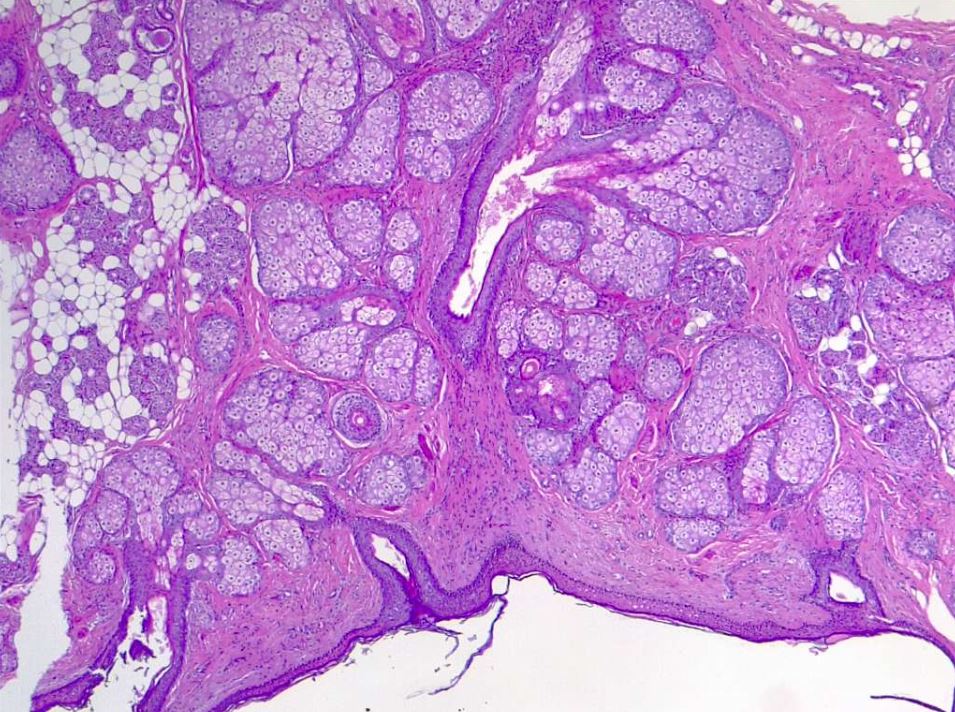

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a disorder affecting 5 to 10% of women of reproductive age and is one of the primary causes of infertility. It is associated with diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease most of the time. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) appears as enlarged ovaries with multiple small follicular cysts. The ovaries appear enlarged due to excess androgen hormones in the body, which cause the ovaries to form cysts and increase in size.[19]

Neoplastic Cysts

These cysts arise from the inappropriate overgrowth of cells within the ovary and may be malignant or benign. They may arise from the surface epithelium, and the benign lesions include serous and mucinous tumors. Other cystic lesions can include stromal or germ cell elements. Stromal masses are more often solid. Germ cell tumors are more often complex. Malignant cysts arise from all ovarian subtypes. These most frequently arise from the surface epithelium and are partially cystic. Epithelial malignancies include serous carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and malignant Brenner tumors. Malignant germ cell tumors include immature teratoma, endodermal sinus tumors, embryonal carcinoma, and polyembryoma.

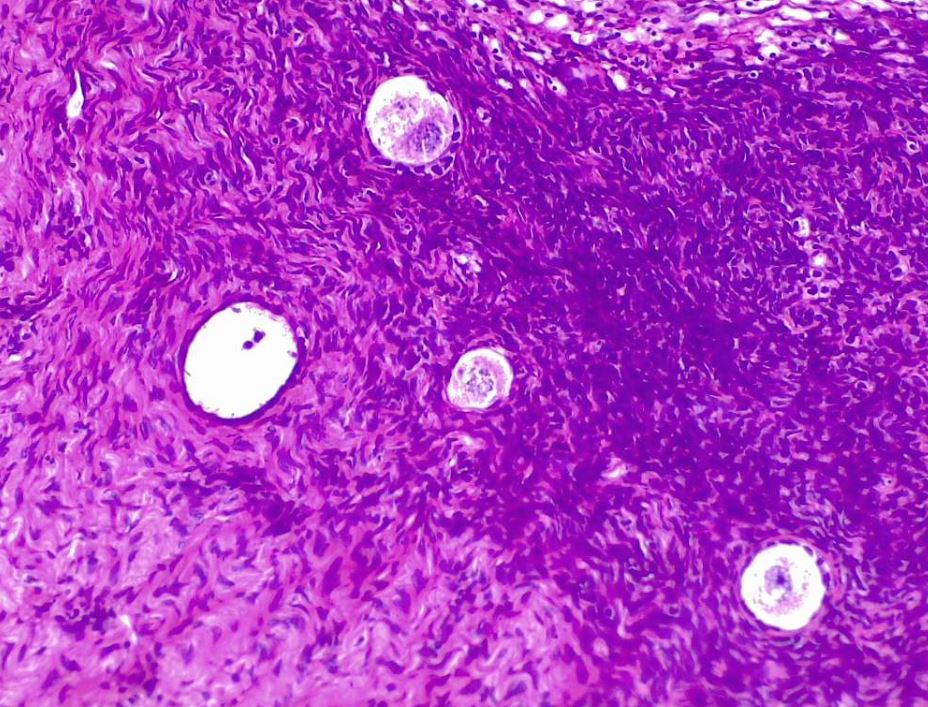

Dermoid cysts or mature cystic teratomas contain elements from all three differentiated germ layers (ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal) and appear complex but can have a variety of appearances due to the tissue they contain. Struma ovarii is a specialized teratoma that consists predominately of mature thyroid tissue and is present in approximately 5% of ovarian teratomas. Although mostly benign, dermoid cysts can undergo a malignant transformation in 1 to 2% of cases.[20][21]

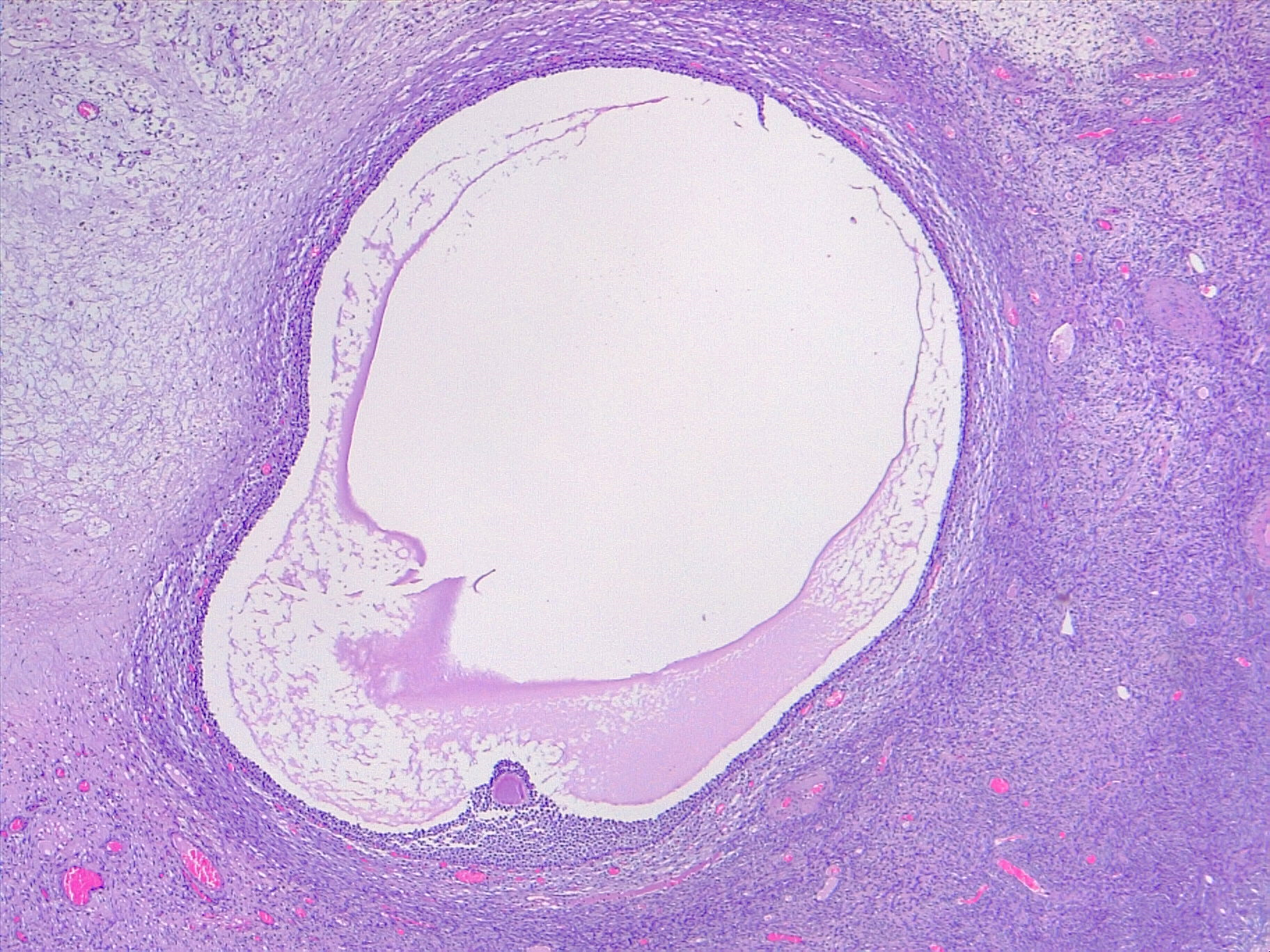

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma at extrauterine sites, with the ovary being one of the most common sites. Endometriomas (common in endometriosis) arise from ectopic growth of endometrial tissue and are often referred to as chocolate cysts because they contain dark, thick, gelatinous aged blood products. They appear as a complex mass on ultrasound and are described as having “ground glass” internal echoes. Endometriomas can be classified into two types. Type I consists of small primary endometriomas that develop from surface endometrial implants. Type II arises from functional cysts that have been invaded by ovarian endometriosis or type I endometriomas. Although the overall risk of malignant transformation is low, endometriomas increase this risk in women with endometriosis.[22][23][24]

History and Physical

Although the majority of ovarian cysts are incidental findings on physical exam or at the time of pelvic imaging, a detailed medical history with particular attention placed on gynecological history, family history, and physical examination should still be performed at each visit. Ovarian cysts can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptoms that women may experience include unilateral pain or pressure in the lower abdomen. Pain may be intermittent or constant and characterized as sharp or dull. If an ovarian cyst ruptures or ovarian torsion is present, the patient may experience a sudden onset of acute severe pain, possibly associated with nausea and vomiting. The menstrual cycle can become irregular, and abnormal vaginal bleed may occur.[25]

On physical examination, palpation of the ovaries on the bimanual exam should help determine location, shape (regular or irregular), size, consistency, level of tenderness, and mobility. The ovaries can be difficult to palpate depending on the patient’s body habitus, provider experience, and pelvic anatomy; therefore, the pelvic examination has limited ability to diagnose ovarian cysts.[5]

Evaluation

When an ovarian mass is suspected, the provider should first determine whether the patient is pre or postmenopausal. If the former is true, the first step is to perform a serum beta hCG or urine pregnancy test. Once pregnancy is ruled out, imaging should be done for further evaluation. A complete blood count should focus on the hematocrit and hemoglobin levels to evaluate for anemia caused by acute bleeding. Urinalysis should be obtained to rule out urinary tract infections and kidney stones. Endocervical swabs should be collected to assess for pelvic inflammatory disease. Cancer antigen 125 (CA125) is a protein present on the cell membrane of healthy ovarian tissues and ovarian carcinomas. A blood level of less than 35U/ml is taken as normal. CA125 values are raised in 85% of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, while it is raised in 50% of patients with stage I cancer confined to the ovary. The finding of an elevated CA 125 level is most useful when combined with an ultrasound while evaluating a postmenopausal woman with an ovarian cyst.[11][15]

Due to the proximity of the transvaginal probe to the ovaries, the most common imaging modality used for an initial evaluation is transvaginal ultrasonography. It is the imaging of choice when attempting to differentiate between benign or malignant mass. Abdominal ultrasonography can be used in conjunction if pelvic anatomy is distorted due to previous surgeries. Ultrasound evaluates for laterality, size, the composition of the mass (cystic, solid, or mixed, septations, papillary excrescences, mural nodules), presence of pelvic free fluid, and assessment of blood flow and vascularity via color doppler. Ultrasound findings consistent with benign cysts in any age group are thin, smooth walls, an absence of septations, solid components, and internal flow on color doppler.

An important concern for patients with pain and adnexal mass is the possibility of torsion, which can lead to necrosis and loss of the ovary. It is important to note that the presence of blood flow on the doppler exam cannot rule out adnexal torsion. This is evident in a case-control study performed with 55 confirmed cases, and 48 controls showed normal doppler flow in 27% of left ovarian torsion cases and 61% of right ovarian torsion cases. The persistence of normal Doppler flow in suspected torsion can be due to intermittent torsion or to the double blood supply of the ovary.[26]

Cyst size greater than 10 cm, complex multilocular mass, papillary excrescences or solid components, irregularity, thick septations, evidence of ascites, and increased vascularity on color doppler should raise suspicion for malignancy and requires further evaluation.[5] Additional imaging studies like magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography can be performed but are not recommended as part of the initial evaluation. Gynecologic oncology consultation should be considered in these cases.[27][28][29]

Treatment / Management

There are several different treatment options available, but ultimately management depends on the patient's age, menopausal status, the size of the cyst, and whether the cyst has characteristics suspicious of malignancy. Unilocular cysts less than 10 cm are usually benign regardless of patient age; therefore, if the patient is asymptomatic, she can be monitored conservatively with serial transvaginal ultrasound since the majority of cysts resolve spontaneously without intervention. If a cyst does not resolve after several menstrual cycles, it is unlikely to be a functional cyst, and further workup is indicated.[30]

Fetal ovarian cysts are caused by hormonal stimulation. Also, an association between fetal ovarian cysts and maternal diabetes and fetal hypothyroidism has been found. Most fetal ovarian cysts are usually small and involute during the first few months of life and are of no significance. These cysts are diagnosed in the third trimester of pregnancy, and most tend to resolve at 2 to 10 weeks postnatally.[8]

Most pregnancy-associated cysts, both corpus luteal and follicular, resolve spontaneously by 14 to 16 weeks of gestation, allowing conservative management.[31] The resolution of cysts is less likely when larger than 5cm or with complex morphology. Simple cysts smaller than 6 cm have only less than 1% risk of malignancy.[32]

In women of all ages, endometriomas should have followed up sonograms 6 to 12 weeks after initial imaging, then yearly until surgically removed. Dermoid cysts should also have a yearly follow-up with ultrasound until surgical removal.

Surgical indications include suspected ovarian torsion, persistent adnexal mass, acute abdominal pain, and suspected malignancy. Surgery in pre-menopausal women prioritizes fertility preservation, and every attempt is made to remove minimal ovarian tissue. Pregnant patients can have cysts that may require surgical management. Although laparoscopy is safe in all trimesters of pregnancy, ideally, it is recommended to perform surgery in the second trimester.[33]

Differential Diagnosis

The ovarian cyst has a broad range of differential diagnoses, broadly classified into gynecological and nongynaecological subcategories.

Gynecological

- Benign: Functional cyst, endometrioma, tubo-ovarian abscess, mature teratoma, serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, para tubal cyst, hydrosalpinx, leiomyomas

- Malignant: Epithelial carcinoma, germ cell tumor, sex cord or stromal tumor, metastatic cancer

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ectopic pregnancy

Nongynecological

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Pelvic kidney

- Gastrointestinal cancer

- UTI

- Nephrolithiasis

- Psoas abscess

Prognosis

Most ovarian cysts are found incidentally, are asymptomatic, and tend to be benign with spontaneous resolution leading to an overall favorable prognosis. Overall, 70% to 80% of follicular cysts resolve spontaneously. The potential of benign ovarian cystadenoma to become malignant has been postulated but remains unproven. Less aggressive tumors of low malignant potential run a benign course. The overall survival in these cases is 86.2% at five years.[31] Malignant change can occur in a few cases of dermoid cysts (associated with extremely poor prognosis) and endometriosis. If an ovarian cyst is suspected to be malignant, the prognosis is usually poor since ovarian cancer tends to be diagnosed in the advanced stages.

Complications

There are three classic complications of ovarian cysts that commonly present to the emergency department:

- Rupture

- Hemorrhage

- Torsion

The fifth most common gynecological emergency is ovarian torsion, defined as the complete or partial twisting of the ovarian vessels resulting in obstruction of blood flow to the ovary. The diagnosis is made clinically with the assistance of a history and physical examination, bloodwork, and imaging and is confirmed by diagnostic laparoscopy. The latest evidence supports a conservative approach during diagnostic laparoscopy, and detorsion of the ovary with or without cystectomy is recommended to preserve fertility. Ovarian cysts can also rupture or hemorrhage, with most of these being physiological. Most cases are uncomplicated with mild to moderate symptoms, and those with stable vital signs can be managed expectantly. Occasionally, this can be complicated by significant blood loss resulting in hemodynamic instability requiring admission to the hospital, surgical evacuation, and blood transfusion.[11]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

When a patient needs surgical management, laparoscopy or laparotomy can be performed, and both have significant advantages and disadvantages. Laparotomy is usually preferred when the patient is hemodynamically unstable since it allows for faster entry and direct visualization of the involved structure but results in larger incisions and increased duration of post-op pain, hospital stay, and recovery time. Laparoscopies are more lengthy procedures with smaller incisions with less risk of infection and blood loss when compared to laparotomies. However, the longer time spent in surgery leads to increased exposure to general anesthesia and increases the risk of damage to internal organs and blood vessels. When laparoscopy is performed, the hemodynamically stable patient is usually discharged home on the same day of surgery with typical post-surgical precautions and proper follow-up scheduled.

Consultations

The management of patients with the ovarian cyst is multidisciplinary, and teamwork is necessary between the following specialties:

- Obstetrician/gynecologist

- Infertility and reproductive endocrinologists

- Gynecologic oncologist

- General surgeon

- Radiologist

- Pathologist

Patients at high risk for ovarian malignancy should have their case reviewed with a gynecologic oncologist for further assessment and determination of optimal surgical management. Specific guidelines can help gynecologists differentiate when to refer patients with an adnexal mass. Typically, postmenopausal women with an elevated CA-125 or premenopausal women with significantly high CA-125, ultrasound characteristics suspicious for malignancy, nodular or fixed pelvic mass, ascites, evidence, or abdominal or distant metastasis should be referred to gynecologic oncology. Ultrasound findings that are suspicious for malignancy include cysts larger than 10 cm, irregularity of cyst, high color Doppler flow, papillary or solid components, and presence of ascites.[5]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled sacs that can present within the ovary and are most commonly benign functional cysts that regress spontaneously. They are commonly found incidentally on examination or imaging. In certain instances, they may become so enlarged that the increased weight may cause the ovary to rotate on itself, cutting off the blood supply and resulting in a gynecologic emergency known as ovarian torsion, which requires surgical management.

Ovarian cysts can also rupture and cause life-threatening hemorrhage. Large cysts should be removed to prevent complications. If one may experience a sudden onset of unilateral moderate to severe sharp lower abdominal pain, associated with or without nausea and vomiting and strenuous activity such as sexual intercourse or exercise, prompt evaluation is mandatory.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Although ovarian cysts are mostly benign and resolve spontaneously, they can sometimes lead to complications such as rupture, hemorrhage, and torsion that require urgent medical or surgical treatment. The evaluation aims to determine the most likely etiology of the patient's symptoms whenever an ovarian cyst is present. Acute lower abdominal pain is a common presentation to the emergency room and can be associated with various generalized symptoms. The differential diagnosis is broad, and it can be challenging to determine the exact cause without proper imaging studies. Transvaginal ultrasound is the recommended first-line imaging modality for a suspected or incidentally identified pelvic mass. [Level 1]

Findings that raise the level of suspicion for malignancy include cyst size of more than 10 cm, presence of ascites, papillary excrescences or solid components, irregularity, and high color doppler flow. [level 1]. Surgical intervention for mature ovarian teratomas or endometriomas is warranted in the masses are large, symptomatic, and growing in size on serial imaging studies or if malignancy is suspected. If, however, expectant management is employed, follow-up surveillance is warranted.[28][29] [Level 2]

As mentioned above, proper diagnosis and management of ovarian cysts require an interprofessional healthcare team that includes physicians (MDs and DOs), specialists, mid-level practitioners (NPs and PAs), and nurses, all sharing patient information and keeping the rest of them informed regarding status changes, new developments, and therapeutic improvement or failure. The interprofessional paradigm will result in better patient outcomes with fewer adverse events. [Level 5]