Introduction

The orbits are bony structures of the skull that house the globe, extraocular muscles, nerves, blood vessels, lacrimal apparatus, and adipose tissue. Each orbit protects the globe, while the supportive tissues allow the globe to move in three dimensions (horizontal, vertical, and torsional).[1][2] The anatomy of the orbit is a complex topic vital for understanding the communication between the eye and the central nervous system and the potential for the spread of malignancy or infection. Certain surgical emergencies, such as severe fractures, are often intricate because of the delicate anatomy of the orbit and its contents.[1][2] The following article will provide insight into the structure and function of the different components of the orbit and will explain the importance of understanding orbital anatomy and physiology in relation to pathology.

Structure and Function

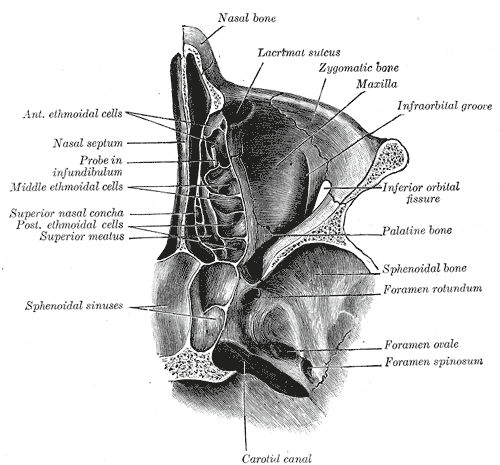

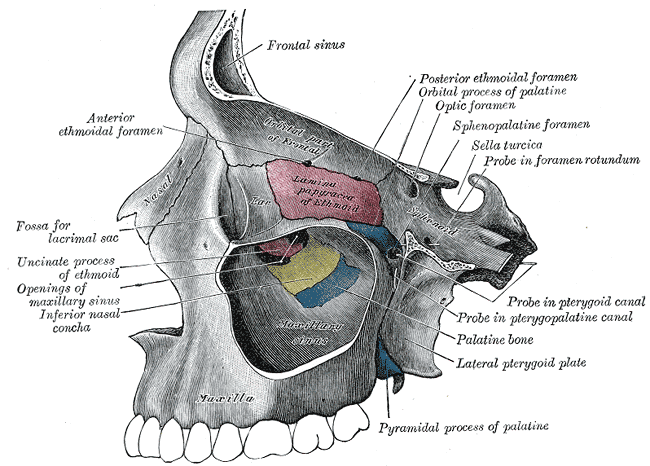

The orbits are symmetrical paired structures separated by the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Seven bones form each orbit: frontal, sphenoid, maxillary, zygomatic, palatine, ethmoid, and lacrimal. The orbital roof is formed by the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone and the frontal bone. The lateral wall comprises the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and zygomatic bone. The medial orbital wall comprises the lacrimal, ethmoid, maxillary, and lesser wing of the sphenoid bones. Finally, the orbital floor comprises the maxillary, palatine, and zygomatic bones.[1][2] The lateral wall is the strongest of the four orbital walls.[2] The walls of the orbit function as a physical barrier from blunt trauma to the eye, an anchor for muscles and ligaments to attach, and additionally serve as a window for neurovasculature to travel through.

Connective tissue structures within the orbit aid in support and protection of the orbital contents. Orbital fat, which surrounds the extraocular muscles and the globe itself, serves as a cushion and facilitates the movement of the eye. The orbital septum is a connective tissue structure that acts as an anterior border between the facial skin and fat and the orbital contents, impeding the spread of infection into the orbit.[2]

The lacrimal gland, a secretory gland comprising acini and ducts, produces tears and maintains the microenvironment of the eye. The location of the main lacrimal gland is near the lateral aspect of the anterior orbital roof, and it comprises two lobes, the orbital and palpebral lobes. Each lobe contains a duct that opens into the superior conjunctival fornix. The accessory lacrimal gland is smaller and is found within the lamina propria of the conjunctiva, with ducts opening onto the conjunctival surface.[3]

Embryology

Orbital development begins in the third week of embryonic life. The optic pits appear first as an invagination of the diencephalon, eventually forming the orbit after contributions from many embryonic cell populations. The cranial neural crest cells are thought to be the fundamental cells of orbital embryogenesis, but the complex interactions between these cells have not been fully elucidated.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

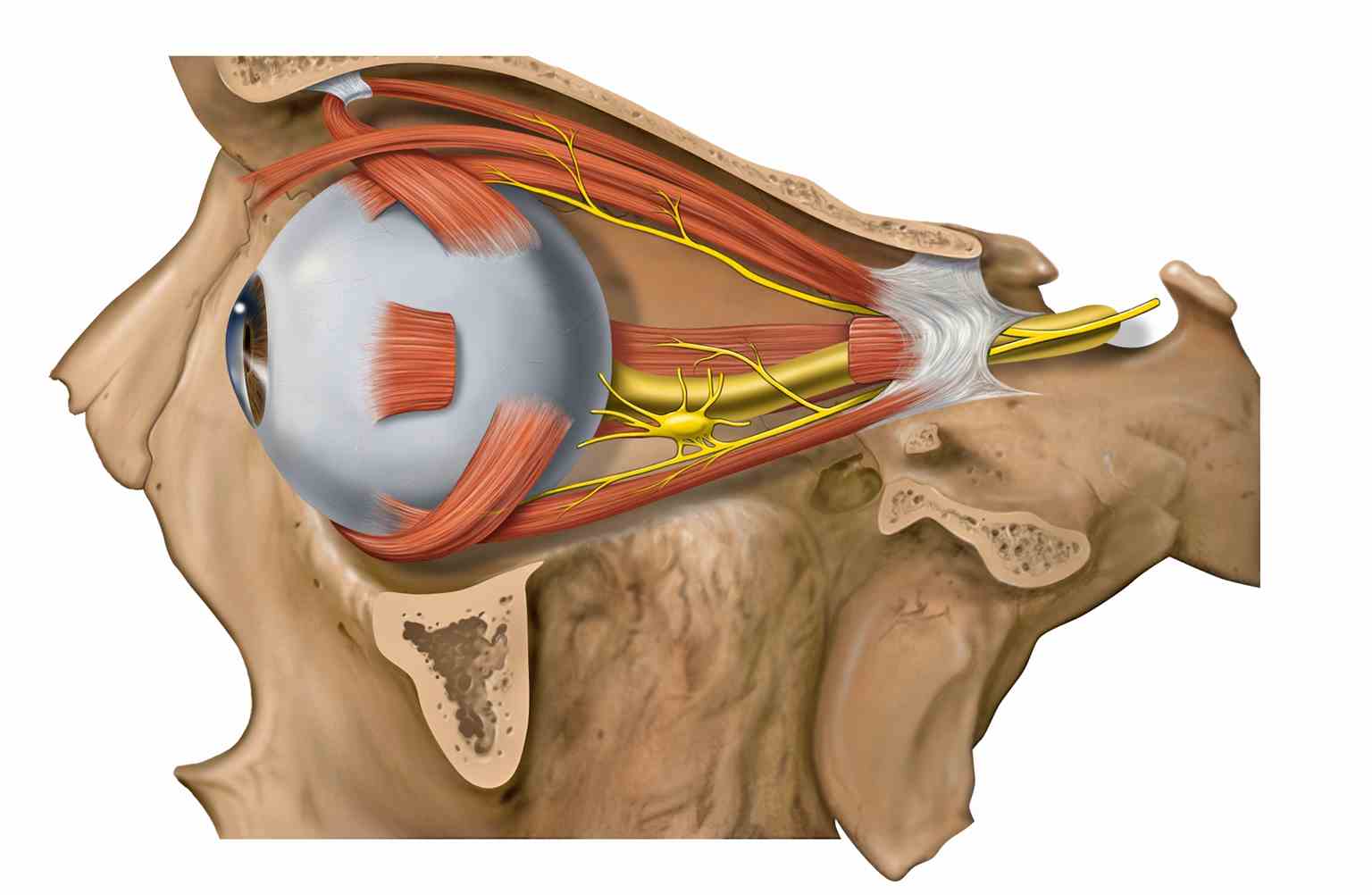

The ophthalmic artery is a branch of the internal carotid artery that courses through the optic canal of the sphenoid bone. Once it enters the orbit, the ophthalmic artery has pierced the dura of the optic nerve where it continues anteriorly. It supplies the central retinal artery (which enters the globe), the lacrimal artery (supplying the lateral rectus muscle, lacrimal gland, eyelids, temporal fossa, and cheeks), and the superior and inferior muscular arteries (which supply the superior rectus and superior oblique muscles, as well as the inferior rectus and medial rectus muscles, respectively).

The infraorbital artery, a branch of the maxillary artery, and the infraorbital vein, which drains into the pterygoid plexus, course through the inferior orbital fissure through the infraorbital canal alongside the infraorbital nerve. These vessels emerge anteriorly from the infraorbital foramen of the maxilla.[1][2]

The superior and inferior ophthalmic veins course through the superior orbital fissure. These veins communicate with the facial veins anteriorly and the cavernous sinus posteriorly. Their exact course is variable, see the "Physiologic Variants" section below.

The eyelids and bulbar conjunctiva use the orbital lymphatic system to drain the preauricular nodes. Controversy exists over the clinical significance of the lymphatic system surrounding the optic nerve and lacrimal gland, however.[3]

Nerves

The infraorbital nerve, a branch of the trigeminal nerve that provides sensation to the maxillary region of the face, courses anteriorly from the inferior orbital fissure. This fissure is located at the posterior aspect of the orbit and meets the infraorbital canal of the orbital floor. The infraorbital nerve courses through the canal and emerges facially from the infraorbital foramen of the maxilla.

The superior orbital fissure allows for the passage of cranial nerves (CN) originating from the cranial fossa to enter the orbit. CN III (oculomotor nerve), CN IV (trochlear nerve) and CN VI (abducens nerve) innervate extraocular muscles, while the first division of CN V (ophthalmic branch), provides sensation to the upper face, mucous membranes, and scalp. CN III innervates the superior rectus muscle, medial rectus muscle, inferior rectus muscle, and inferior oblique muscle. CN IV provides innervation to the superior oblique muscle, and CN VI innervates the lateral rectus muscle.

The optic canal is located medially to the superior orbital fissure and transmits the optic nerve (CNII). The optic nerve transmits visual input from the retina to the brain.[1]

Muscles

The levator palpebrae superioris muscle, which receives nerve supply from CN III, elevates the upper eyelid. It is superior to the superior rectus muscle at the roof of the orbit, and these two muscles join in a common aponeurosis anteriorly. This intimate muscular relationship explains why the eye elevates as the upper eyelid is retracted.

The extraocular muscles and their actions are as follows:[2]

- Superior rectus: Elevates, adducts and rotates medially

- Medial rectus: Adducts

- Inferior rectus: Depresses, adducts and rotates laterally

- Lateral rectus: Abducts

- Superior oblique: Depresses, abducts, and rotates medially

- Inferior oblique: Elevates, abducts, and rotates laterally

Physiologic Variants

Several variant neural connections exist in the orbit. A significant proportion of these neural connections involve the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) and extraocular muscles. These communications include branches of V1 merging with: inferior and superior divisions of CN III, CN IV, CN VI, carotid plexus, superior rectus muscle, medial rectus muscle, and levator palpebrae superioris muscle.[5]

The venous system of the orbit is also highly variable, as a dense anastomotic network is typically present. There is no single venous correlate to the ophthalmic artery. Instead, there is a superior ophthalmic vein and a variable inferior ophthalmic vein. The two ophthalmic veins may drain to the cavernous sinus independently or join first before entering the cavernous sinus.[2]

Surgical Considerations

One must take extreme care during orbital surgery to preserve the delicate anatomy of the orbit. Entering the orbit surgically is performed via the potential space between the walls of the orbit anteriorly and the probate. Because of the proximity of the orbit to the intracranial cavity, it takes care to avoid introducing infection through several foramina and apertures of the orbital walls.[2]

Clinical Significance

The facial veins communicate directly with the ophthalmic veins and serve as a conduit for infection from the face towards the cavernous sinus.[2]

Severe fractures that extend into the optic canal can lead to hemorrhage from the ophthalmic artery or blindness from damage to the optic nerve.

Extraocular Muscle/Neurologic Pathology:[2]

- Patients with a "down and out" gaze may have oculomotor nerve palsy

- Patients unable to abduct their eye may have a lateral rectus/CNVI palsy