Continuing Education Activity

The paramedian forehead flap is a highly versatile surgical technique utilized in nasal reconstruction, particularly for addressing extensive or intricate defects spanning multiple nasal subunits. This approach leverages the robust axial blood supply provided by the supratrochlear artery, facilitating dependable tissue transfer and optimal wound healing. The procedure demands meticulous planning and execution, emphasizing precise flap design, elevation, and inset to ensure vascular integrity and achieve desirable aesthetic outcomes. Despite potential complications such as flap necrosis or venous insufficiency, successful reconstruction with minimal morbidity and satisfactory cosmetic results is attainable through proper patient selection and perioperative management.

Through active participation in this course focused on paramedian forehead flap reconstruction, clinicians are equipped with comprehensive knowledge and skills essential for proficiently performing this intricate procedure. Learners delve into the intricacies of vascular anatomy, flap design principles, surgical techniques, and strategies for managing potential complications. Furthermore, collaboration with an interprofessional team comprising surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals enhances patient outcomes by facilitating seamless coordination throughout the surgical journey. Effective communication and collaboration among team members enable thorough patient assessments, personalized treatment planning, and vigilant monitoring postoperatively.

Objectives:

Identify the vascular anatomy relevant to paramedian forehead flap surgery.

Differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate candidates for paramedian forehead flap reconstruction.

Implement proper surgical techniques for paramedian forehead flap harvest, transfer, and inset.

Collaborate with all interprofessional team members to provide efficient, safe, and coordinated care for patients undergoing paramedian forehead flap transfer to maximize functional and aesthetic outcomes while minimizing complications.

Introduction

Interpolated flaps, rotation, and transposition flaps comprise the pivotal flap category of facial reconstruction techniques.[1][2][3] Interpolated flaps differ from other pivotal flaps in that the flap's base (or pedicle) is not contiguous with the defect and necessarily passes across intervening tissue between the defect and the flap harvest site. Many surgeons would classify interpolated flaps as regional flaps rather than local flaps, given that the tissue used to reconstruct the defect when an interpolated flap is transferred is not originally adjacent to the defect.

While numerous interpolated flap options may be employed in facial reconstruction (nasolabial flaps, temporoparietal fascia flaps, pericranial flaps, inferior turbinate flaps, facial artery musculomucosal flaps, and temporalis muscle flaps, among others), the forehead flap has remained a workhorse technique since Gillies popularized it during World War I.[4] Gillies' protégé, Millard, was the first to describe basing the flap in a paramedian position to include a single set of supratrochlear vessels as an axial blood supply.[5] Nevertheless, the flap's origins stretch back to at least 600 BC, when it was described in the Indian medical text Sushruta Samhita as a midline forehead flap for repair of nasal defects arising from punitive mutilation.[6][7] The sebaceous gland quality and thickness of central forehead skin closely resemble those of the nose, and the flap's vascularity is highly reliable, which is why this technique has been selected for nasal reconstruction so consistently throughout history.[8][9]

Using the paramedian forehead flap in nasal reconstruction typically requires at least a 2-stage procedure, with operations usually separated by 3 weeks. Some surgeons prefer to utilize a third stage to permit further refinement of the flap's contour.[10][11][12] Even though flap harvest necessarily leaves a vertical scar on the forehead, it is not always particularly conspicuous—and the ultimate cosmetic and functional outcomes tend to be very acceptable to patients and surgeons alike.

Anatomy and Physiology

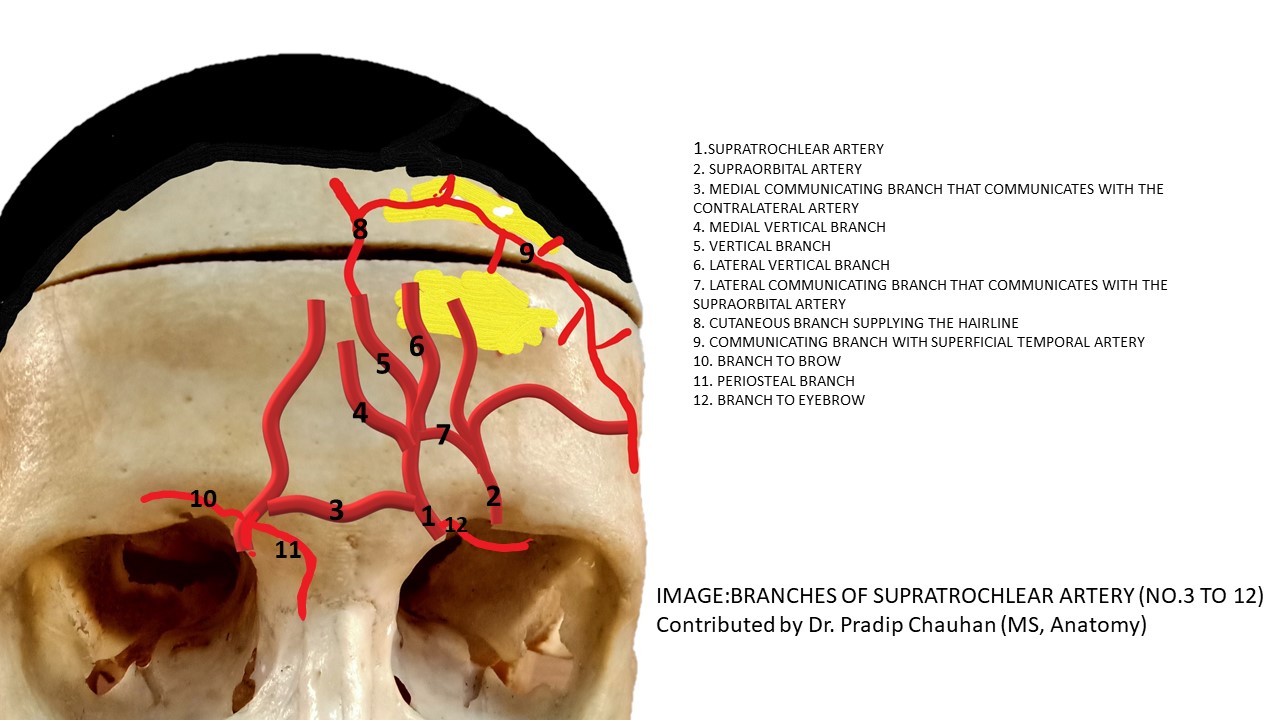

When considering paramedian forehead flap reconstructions, conceptualize the forehead in 3 distinct regions, each with different blood vessels: central, lateral, and temporal. The central forehead tissue can be transferred as a paramedian forehead flap based upon a unilateral pedicle with enough skin to resurface an entire nose. The flap is perfused entirely by branches of the supratrochlear artery and drained by their corresponding veins, thus giving the flap a specific axial blood supply rather than requiring it to rely upon random perfusion via the subdermal plexus.[13] Understanding the vascular anatomy ensures adequate tissue perfusion and awareness of soft tissue planes facilitates efficient flap elevation.

Deep to the dermis is a thin layer of subcutaneous fat, underneath which lies the frontalis muscle (the only elevator of the brows), and this becomes contiguous with the galea aponeurotica superiorly, near the hairline. Deep to the frontalis muscle is a loose areolar plane that separates it from the underlying pericranium and frontal bone. Inferiorly, near the superior orbital rim, the orbicularis oculi muscle is directly adherent to the deep surface of the dermis without a significant amount of fat intervening between the 2 layers. The corrugator supercilii muscle, which depresses the medial brow and causes vertical glabellar lines, is situated deep to the orbicularis oculi, which closes the eye and depresses the lateral brow. The procerus muscle, which produces horizontal rhytides, is superficial to the corrugators, extending from the midline of the glabella into the nasal radix.

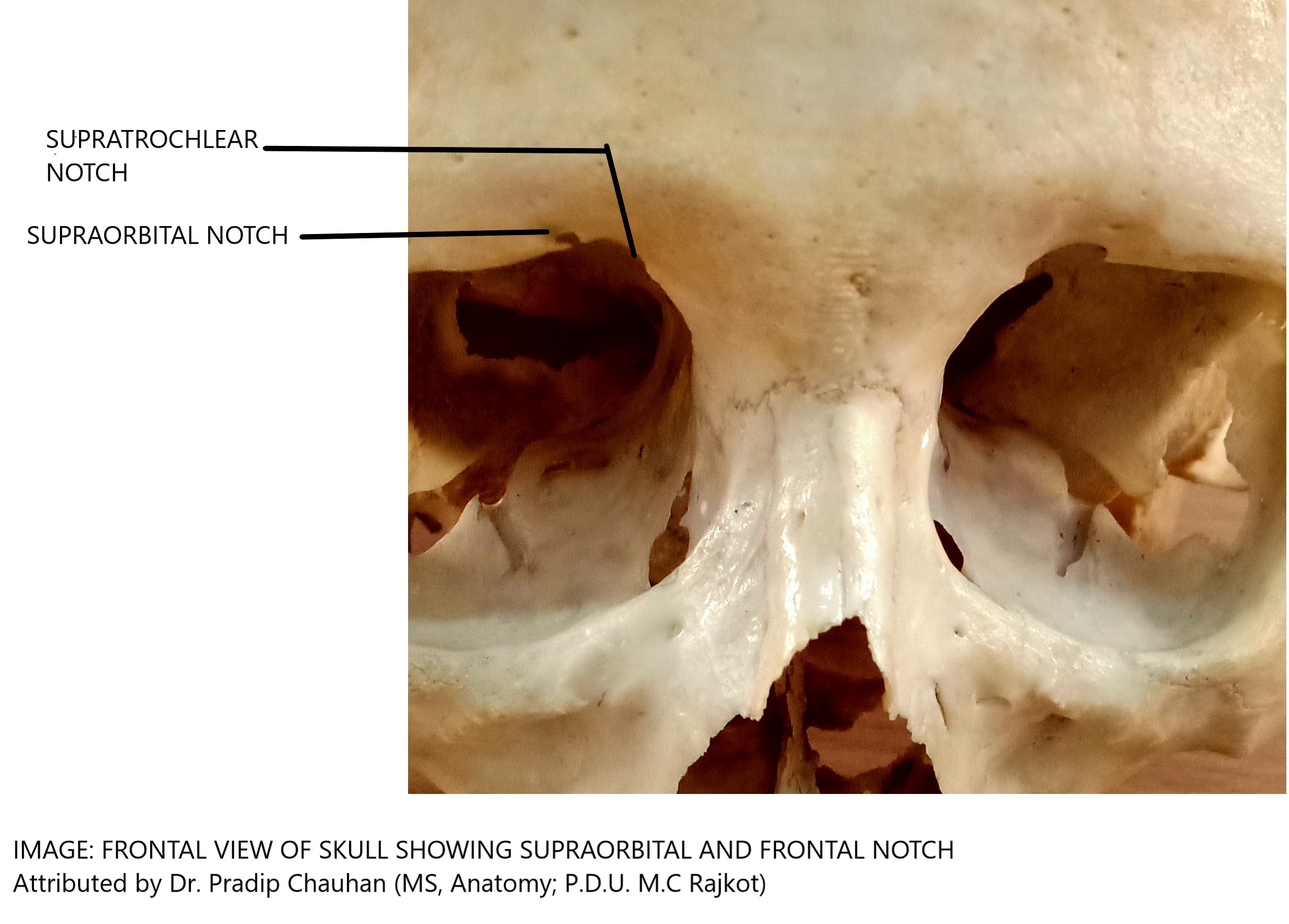

Perfusion of the forehead comes from a network of arterial anastomoses among the supratrochlear, supraorbital, superficial temporal, and dorsal nasal (a branch of the angular artery) vessels (see Image. Supratrochlear Artery Branches). The supratrochlear artery exits the orbit through the orbital septum and passes between the orbicularis oculi (superficially) and the corrugator supercilii (deeply).[14] The supratrochlear artery arises from the internal carotid arterial system via the ophthalmic artery, exits the superior medial orbit 1.7 to 2.2 cm lateral to the midline, accompanied by the supratrochlear nerve, and continues vertically, with the medial head of the eyebrow approximating where the artery pierces the orbital septum and crosses the superior orbital rim (see Images. Supratrochlear and Supraorbital Notches and Supraorbital and Supratrochlear Neurovascular Bundles).[15]

Immediately after reaching the forehead, a periosteal branch diverges from the main artery, which may be used to perfuse a pericranial flap.[16][17] Coursing superiorly, the supratrochlear artery then passes between the orbicularis oculi and the frontalis muscles (on its superficial surface) and the corrugator supercilii (on its deep surface).[18] This artery runs deep to the frontalis for 2 to 3 cm before traversing the muscle and becoming a subcutaneous vessel for the remainder of its course.[19][20][21] Therefore, the paramedian forehead flap should be designed to include the supratrochlear blood supply, including deep tissue at the most inferior 3 cm, where the vessel's course deep to the frontalis muscle, and more superficial tissue superior to that point because the vessels run in a subdermal plane towards the vertex of the scalp.[15] The supratrochlear vein provides venous outflow to the medial forehead, superior orbital margin, and glabella.[22] This vein courses alongside the supratrochlear artery and drains into the angular vein, as does the supraorbital vein.[23]

Indications

The primary indication for employing a paramedian forehead flap is the reconstruction of sizable nasal defects, although its utility extends to periocular and skull base reconstruction.[24][25] Typically, defects exceeding 1.5 to 2 cm in diameter are best suited for this technique, as smaller defects can often be managed with single-stage approaches like bilobed flap transfer or skin grafting.[26] However, skin grafting is limited in cases where substantial perichondrium or periosteum loss precludes the establishment of a vascularized wound bed necessary for graft healing.[27]

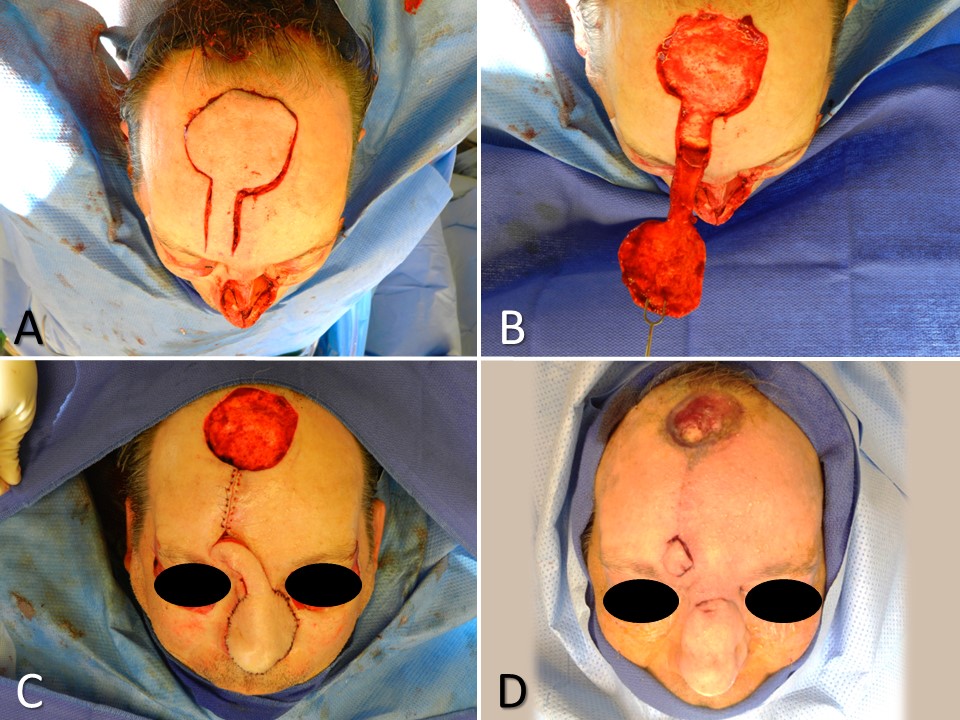

Paramedian forehead flaps offer ample skin coverage to replace multiple nasal subunits, particularly beneficial when over 50% of a subunit is lost, warranting full subunit replacement for optimal aesthetic outcomes.[8] Commonly reconstructed subunits with paramedian forehead flaps include the nasal tip, columella, soft tissue triangles, alae, and dorsum. Yet, alternatives like Rieger flaps for dorsum or nasolabial flaps for reconstruction may be preferred in isolated cases.[28][29] For extensive defects like rhinectomies, paramedian forehead flaps are a viable alternative to free tissue transfer, such as radial forearm flaps (see Image. Paramedian Forehead Flap for Nasal Reconstruction). Some surgeons also perform complex, multistage, and multilayer procedures in which paramedian forehead flaps are folded or wrapped around structural elements like bone, cartilage, or titanium plates to reconstruct total nasal defects.[30][31][32]

Contraindications

While the paramedian forehead flap is a versatile option for nasal defect reconstruction, certain patient factors may deem it less suitable. These include smoking habits, which can impair healing due to vasculopathy, reluctance to accept a forehead scar, and patients with low hairlines, which can potentially cause excessive hair growth on the flap. Concurrent forehead wounds, infections, lesions, and disrupted supratrochlear blood supply from prior surgeries also warrant alternative approaches. Additionally, patients who are cognitively unable to participate in self-care between surgical stages, and especially those prone to manipulating the flap's pedicle, are likely better served with a different reconstructive option.

Equipment

Equipment required for flap elevation, transfer, inset, and pedicle division is very similar and should include, at a minimum:

- Surgical marker

- Local anesthetic (1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine or similar) and hypodermic syringe with a fine needle (27- or 30-gauge)

- Foil suture packet or similar material for use as a flap template

- Surgical sponges

- Doppler ultrasound probe

- Measuring tape or calipers

- #15 blade scalpel and #3 Bard-Parker handle

- Electrocautery (monopolar or bipolar)

- Dissecting scissors (Kaye blepharoplasty, strabismus, or small Metzenbaum)

- Forceps (Adson-Brown or similar)

- Needle driver (Halsey or similar)

- Suture scissors (Mayo or similar)

- Periosteal elevator (Freer, Cottle, or Joseph)

- Skin hooks

- Sutures for closing the flap harvest site and for insetting the flap

Personnel

Personnel requirements for paramedian forehead flap transfer are minimal, typically involving a surgeon, nurse, and assistant or surgical technologist. An anesthesia provider may be necessary if sedation or general anesthesia is required for larger or more complex cases. Additionally, specialized nursing or support staff may be needed for preoperative preparation and postoperative care. The presence of a multidisciplinary team ensures optimal patient safety and outcomes throughout the surgical procedure.

Preparation

Patient Counseling

Patient education and counseling are critical to a successful outcome, mainly because of the inconvenience and potential social consequences of the flap pedicle's appearance between the initial and final stages of the procedure. Patients should be informed about potential postoperative effects such as bruising, swelling, bleeding, infection, and the eventual scar's appearance. Emphasis should be placed on understanding the presence of the flap pedicle between the forehead and nose, especially if a delay occurs before division. Additionally, education on wound care for the donor site and pedicle, smoking cessation, follow-up appointments, reconstruction goals, and outcome expectations is essential for optimal patient understanding and cooperation.

Preoperative Preparation

Before surgery, precise measurements of the defect and careful consideration of the flap's dimensions are crucial. Evaluating the height of the anterior hairline and assessing forehead laxity are also vital steps. In smokers, a thorough examination of the supratrochlear artery using a Doppler probe is necessary to detect any obstructions. Local anesthetic is administered, and the patient's face, extending into the hairline, is prepped with an antiseptic solution, typically povidone-iodine.

Technique or Treatment

Lidocaine 1% with 1:100,000 epinephrine, either alone or in combination with bupivacaine 0.25% in equal parts, is injected deeply across the entire forehead. In addition, the nose's dorsum and the flap's base are injected. Before flap elevation, any necessary debridement and incision along the margins of the nasal defect, perpendicular to the wound bed, are performed using a scalpel to remove the remaining affected aesthetic subunit.

Flap Elevation and Inset

The paramedian forehead flap is meticulously designed to encompass the supratrochlear vessels within its base and pedicle, utilizing surface landmarks and Doppler ultrasonography when necessary. A customized wound template is fashioned, often from the foil of a suture packet, to shape the skin paddle at the flap's distal end on the superior forehead. For patients with low anterior hairlines or those for whom the flap will be used in columellar reconstruction, the flap may be designed with a lateral curve to avoid using hair-bearing skin on the distal aspect of the flap. However, when the flap extends into hair-bearing scalp areas, meticulous dissection in a subcutaneous plane is employed to identify and remove hair bulbs. If the defect is large, elevation in a subcutaneous plane can also be advantageous because it will expedite healing by secondary intention, compared to a donor site wound extending down to the galea or periosteum. On the other hand, if the nasal defect is deep, elevating the flap in a submuscular/subgaleal plane will provide more bulk to the reconstruction. Elevation proceeds from superior to inferior, carefully approaching the origin of the supratrochlear vessels at the superior orbital rim.

When complex nasal defects involve bone, cartilage, or mucosa alongside skin, various advanced techniques are available for reconstruction. Chimeric paramedian forehead flaps combine different tissue types for comprehensive repair. In the absence of the mucosal lining due to a full-thickness defect, options like inferior turbinate or septal mucosal pivot flaps can be incorporated.[33][34] Alternatively, the paramedian forehead flap may be prelaminated, a procedure in which the flap is elevated, and a split-thickness skin graft is placed on its deep surface for future use as the mucosal component of the reconstruction.[35][36] The flap is then replaced into the forehead and transferred to the defect 3 weeks later as though it were the first stage of a non-prelaminated flap. Allowing time between the placement of the skin graft and transfer of the flap both permits the skin graft to adhere to the flap and develop a vascular supply as well as delaying the flap itself, ie, improving perfusion of the distal aspect of the flap by providing time for choke vessels to open before the pedicle is stressed by rotation.

Prelamination may also include placement of split calvarial bone or septal, auricular, or costal cartilage grafts during the first stage of the operation.[30] Depending upon surgeon preference, these grafts may also be placed at an intermediate stage. On the other hand, some authors prefer to transfer 2 paramedian forehead flaps, 1 to reconstruct the skin and 1 for the mucosal lining, or a paramedian forehead flap for the skin and a pericranial flap for the mucosa.[37][38] A single, large paramedian forehead flap may also be elevated and then folded upon itself to produce 2 mucosalized surfaces to reconstruct skin and mucosa.[39] For the larger defects that require these types of complex reconstructions, a 3-dimensional-printed scale model of the patient's nose may assist the surgical team with intraoperative flap design if a computed tomography scan can be completed before the creation of the defect.[40]

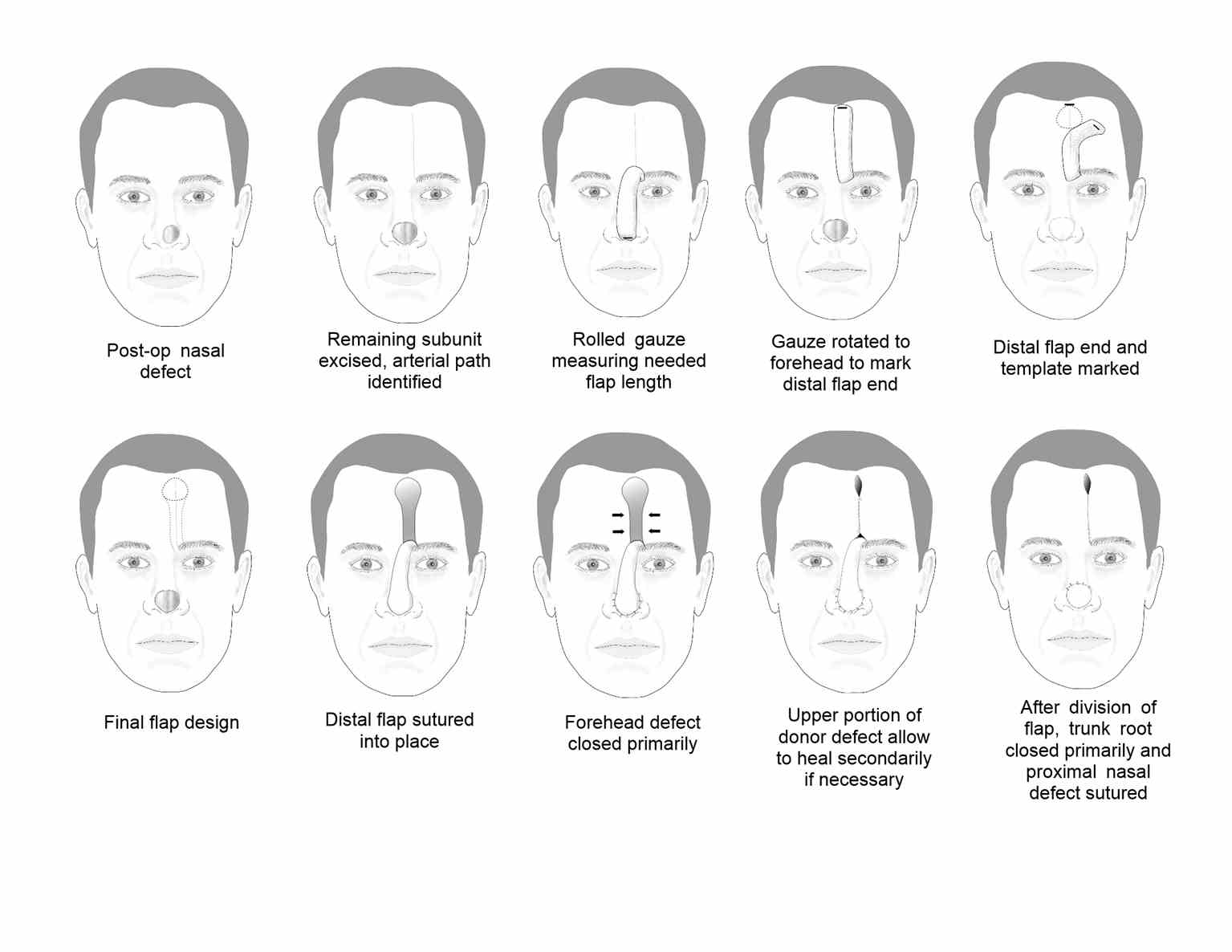

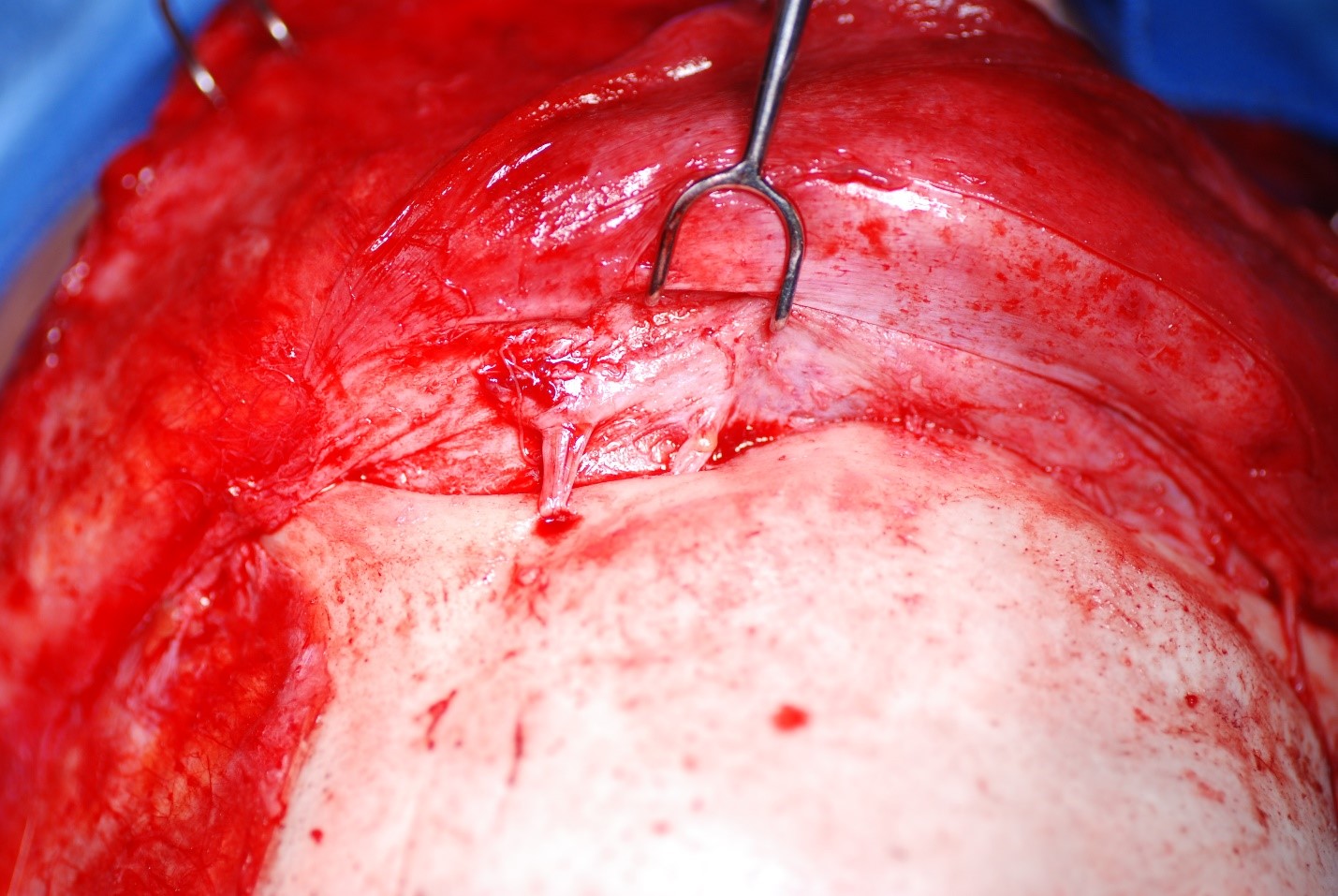

The pedicle of the paramedian forehead flap is meticulously elevated in a submuscular plane beneath the frontalis muscle, ensuring optimal vascular integrity. A delicate balance must be struck to achieve an ideal width centered on the supratrochlear vessels, typically 1.5 to 2 cm. A narrow pedicle risks incomplete vessel inclusion, while excessive width increases the likelihood of kinking during rotation, compromising perfusion. Surgeons estimate pedicle length using a surgical sponge, anchoring 1 end at the medial eyebrow and the other rotated down to the defect, which will give the surgeon an idea of how much length will be lost during the 180° flap rotation (see Image. Forehead Flap Summary Diagrams). Flap orientation, contralateral to the larger defect portion (if the defect is not perfectly midline and symmetric), minimizes pedicle kinking and reduces vascular compromise risks, enhancing flap viability.

The flap elevation progresses to a subperiosteal plane approximately 3 cm above the superior orbital rim to encompass the supratrochlear vessels deep into the frontalis muscle. Careful dissection is crucial, especially when extending inferiorly beyond the orbital rim to enhance flap length or mobility, as the supraorbital artery may be at risk of injury. Following elevation, nasal skin around the defect periphery is undermined, and the flap is rotated into position. Thickness adjustment ensures a proper fit, minimizing the risk of a pincushion deformity before suturing.

If the nasal defect approaches within 5 mm of the alar margin, placing a rim graft of harvested septal or auricular cartilage is recommended to prevent postoperative alar notching. Following this, the flap is sutured into the defect with careful attention to wound edge eversion. The proximal aspect of the flap near the nasal dorsum is left unsutured until pedicle division in a subsequent procedure. Closing the forehead donor site involves undermining and multilayer suturing to reduce tension and prevent widened scars or postoperative headaches. If part of the wound is left to heal via secondary intention, scar revision may be necessary later. For patients willing to undergo a prolonged and uncomfortable treatment regimen, however, a tissue expander may be placed several weeks before elevation and transfer of the flap, which will facilitate both obtaining sufficient tissue to reconstruct even substantial nasal defects as well as primary closure of the donor site, thus minimizing the postoperative scar.[41]

Optionally, some surgeons place a skin graft on the pedicle's exposed submuscular/subgaleal surface to promote hemostasis and prevent the patient from enduring 3 weeks of drainage. If a skin graft is not placed, petrolatum gauze may be wrapped around the pedicle instead.

Intermediate Stage

After 3 weeks, the skin flap can be carefully lifted from the defect and further thinned to improve contour by removing muscular and subcutaneous tissue.[42] This recontouring is typically well tolerated since the flap has undergone a 3-week delay. Cartilaginous support may also be placed at this time. Three weeks after the intermediate stage, the pedicle may be divided.

Pedicle Division

In the final stage of reconstruction, conducted 3 weeks later, the flap's pedicle is divided, and any unused portions are excised except for a triangle of skin used to restore the medial aspect of the eyebrow from which the flap was harvested. Precise repositioning of the pedicle's base into the eyebrow is critical for optimizing aesthetic outcomes. Care must be taken to ensure that the remaining skin triangle does not protrude above the eyebrow level upon reinsertion into the glabella, thus avoiding a peninsula-like appearance. Wide undermining and meticulous suturing are employed to prevent a trap door deformity, ensuring proper closure of the brow.

A notable innovation in paramedian forehead flap transfer is the single-stage procedure, where the pedicle is de-epithelialized and buried, eliminating the need for a second stage for pedicle division.[43] This technique involves creating a tunnel under the nasal dorsum soft tissue to connect the defect to the flap's pedicle base, akin to pedicled pericranial flap transfer for nasal septal reconstruction.[44] The primary advantage is the absence of a visible pedicle across the midface for weeks, potentially improving healing outcomes by preserving the axial blood supply. The drawback, however, is the additional bulk of the pedicle that runs underneath the dorsal nasal soft tissue; that said, revision surgery for dorsal recontouring appears infrequent.[43] This single-stage approach can also be applied to periocular reconstruction, particularly of the medial canthus and eyelid.[45]

Final Revisions

Further interventions should be deferred for several months to allow the flap's scarring, contraction, and maturity to evolve. Dermabrasion, contouring, and depilation may be performed at a later date.

Complications

In 2019, Chen et al conducted a study involving 2175 patients who underwent paramedian forehead flap transfer, revealing infection as the most prevalent complication, affecting 2.9% of patients. Postoperative bleeding was the second most common complication, occurring in 1.4% of patients.[46] Bleeding typically occurs within the first 12 hours after surgery at the raw borders of the pedicle but can be prevented through intraoperative cauterization and patient counseling to avoid strenuous activities. Likewise, placing a skin graft on the raw surface of the pedicle or wrapping it in petrolatum gauze also decreases bleeding. While bleeding may lead to hematoma formation, evacuation is advised to prevent infection and reduce pressure on the flap, improving circulation and viability. Despite the flap's robust axial blood supply, flap ischemia and necrosis can still occur in less than 1% of cases.

Flap necrosis often stems from venous insufficiency, triggered by pedicle kinking, tension, or supratrochlear venous damage. Venous congestion manifests as firmness, edema, and ecchymosis, with dark blood upon pricking. Venous congestion can be treated with serial needle pricks or medical leeches to remove the stagnant blood, or a return to the operating room may be required to adjust the flap. A fluoroquinolone antibiotic should be administered prophylactically to prevent soft tissue infection with Aeromonas hydrophila if leeches are applied. Timely recognition and prompt correction of venous insufficiency is paramount, as prolonged venous congestion will ultimately obstruct arterial inflow.

Arterial insufficiency presents as a cool, pale flap with diminished capillary refill and minimal, if any, bleeding upon needle pricking. Nitroglycerin paste may help if vasospasm is the cause, but caution is warranted in patients with heart conditions.[47] If an intraoperative arterial injury occurs, the flap may need to be discarded and another transferred from the other side. In any case, skin necrosis should be managed with minimal debridement and application of antibiotic ointment. Even if epithelial sloughing occurs, the deeper tissue of the flap may still facilitate healing of the defect, and the eschar can serve as a biological dressing in the interim.

Patients with tobacco use, hypothyroidism, hypertension, or those undergoing auricular cartilage grafting or additional tissue transfer may require overnight admission. Those experiencing postoperative bleeding, neurological disorders, or alcohol use disorder are more likely to return to the emergency room or be readmitted within 48 hours after surgery.[46]

In the long term, scarring of the forehead or distortion of the nose or eyebrow may occur, which can often be addressed with revision surgery or skin resurfacing procedures. Laser hair removal or electrolysis may be necessary if scalp hair grows on the flap. In some cases, contraction of the wound bed beneath the flap or transfer of a flap too large for the defect may result in a "pincushion" deformity, where the flap raises above the surrounding skin in a rounded, pincushion-like fashion. Triamcinolone injection is typically used initially to manage this, but revision surgery may be needed. Similarly, the "trap door" deformity, characterized by the flap elevated above the surrounding skin, particularly along its inferior border due to compromised lymphatic and venous drainage, may require steroid injection, skin resurfacing, or edge camouflage with serial Z-plasty.[48]

Clinical Significance

The paramedian forehead flap is generally employed as a staged, interpolated flap and is most commonly used to reconstruct larger nasal defects. Widely considered a workhorse in facial reconstruction, it may also be employed outside the nose, eg, in the periocular region and the anterior skull base.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Successfully treating patients undergoing paramedian forehead flap procedures requires a collaborative effort among various healthcare professionals, including physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other team members. Physicians and advanced practitioners should possess advanced surgical skills and expertise in facial reconstruction techniques to ensure precise flap elevation, transfer, and inset. They should also employ strategic planning when designing the flap, considering the patient's unique anatomy and the extent of the nasal defect. Interprofessional communication is essential for effective care coordination, with open dialogue among team members regarding patient status, surgical plans, and postoperative care protocols. Nurses play a crucial role in patient education, preoperative preparation, and postoperative monitoring, while pharmacists ensure appropriate medication management, including prophylactic antibiotics and pain management. Close collaboration with pharmacists can help prevent drug interactions and adverse reactions. By fostering a patient-centered approach, leveraging each professional's expertise, and emphasizing communication and coordination among healthcare team members, patient outcomes, safety, and team performance can be optimized in paramedian forehead flap procedures.