Continuing Education Activity

Altered mental status is a common presentation. It is important to recognize the early signs of altered mental status, identify the underlying cause, and to provide the appropriate care to reduce patient morbidity and mortality. The differential diagnosis is broad, and health care providers should be aware of this breadth. Underlying etiology can be as subtle as a urinary tract infection and as life-threatening as an embolic or hemorrhagic stroke. This activity outlines the approach toward differential diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment plans for patients presenting with altered mental status.

Objectives:

- Summarized the importance of history taking and physical exam in the formation of a differential diagnosis.

- Outline the differential diagnosis for altered mental status in different age groups.

- Explain when the assessment of the Glasgow coma score should be done in conjunction with a mental status exam.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance patient care in the hospital and at the time of discharge for patients with mental status changes.

Introduction

The evaluation and management of altered mental status are broad and require careful history and physical examination to eliminate life-threatening situations. Changes in consciousness can be categorized into changes of arousal, the content of consciousness, or a combination of both. Arousal includes wakefulness and/or alertness and can be described as hypoactivity or hyperactivity, while changes in the content of consciousness can lead to changes in self-awareness, expression, language, and emotions [1] [2].

Changes in mental status can be described as delirium (acute change in arousal and content), depression (chronic change in arousal), dementia (chronic change in arousal and content), and coma (dysfunction of arousal and content) [2].

Delirium is typically an acute confusional state, defined by impairment of attention or cognition that usually develops over hours to days. Some patients may experience rapid fluctuations between hypoactive and hyperactive states, that may be interjected with periods of intermittent lucidity. A nearly pathognomonic characteristic of delirium is sleep-wake cycle disruption, which leads to “sundowning,” a phenomenon in which delirium becomes worse or more persistent at night [3][4].

Depression is characterized by personal withdrawal, slowed speech, or poor results of a cognitive test. Patients rarely have a rapid fluctuation of symptoms and are usually oriented and able to follow commands [1][4][3].

Dementia is a slow, progressive loss of mental capacity, leading to deterioration of cognitive abilities and behavior. There are multiple types of dementia, but the most common are idiopathic (also referred to as Alzheimer disease) and vascular dementia. Idiopathic dementia is defined by the slow impairment of recent memory and orientation with remote memories and motor and speech abilities preserved. As the disease progresses, patients exhibit decreased performance in social situations, the inability to self-care, and changes in personality. Vascular dementia is similar to Alzheimer disease, although patients may have signs of motor abnormalities in addition to cognitive changes, and may exhibit a fluctuating step-wise decline, as multiple vascular events have an additive effect on the patient’s function [1][4][3].

Coma is a complete dysfunction of the arousal system, in which patients do not respond to basic stimuli but often retain brain stem reflexes [2].

Etiology

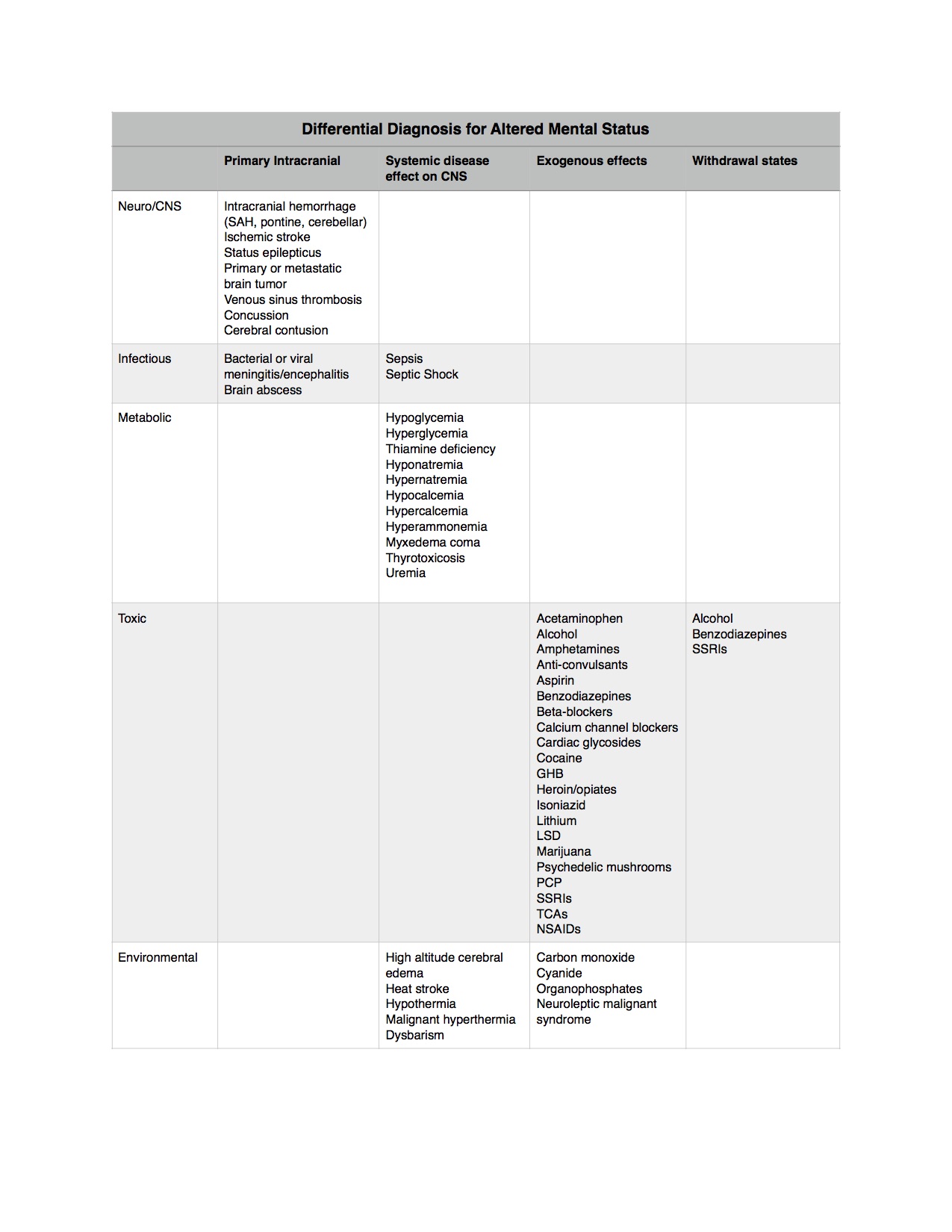

Differential diagnosis is vast, but can typically be sorted into the following categories: primary intracranial disease, a systemic disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS), exogenous toxins, and drug withdrawal. Please see the table for further classification of differential diagnoses.

Epidemiology

In infants and children, the most common causes of altered mental status include infection, trauma, metabolic changes, and toxic ingestion. Young adults most often present with altered mental status secondary to toxic ingestion or trauma. The elderly most commonly will present with altered mental status due to stroke, infection, drug-drug interactions, or alterations in the living environment. In the elderly, nearly 10% to 25% of hospitalized patients will have delirium at the time of admission [1][3][4].

Pathophysiology

The ascending reticular activating system is the anatomic structure that mediates arousal. Neurons of the ascending reticular activating system are located in the midbrain, pons, and medulla, and control arousal from sleep. Metabolic conditions, likely hypoglycemia or hypoxia, can decrease acetylcholine synthesis in the central nervous system, which correlates with the severity of delirium.

Alzheimer dementia is characterized by a reduction of neurons in the cerebral cortex, increased amyloid deposition, and production of neurofibrillary tangles/plaques; vascular dementia is characterized by evidence of cerebrovascular disease with multiple infarctions.

Coma can be secondary to a deficiency of substrates needed for neuronal function, such as in glucose in hypoglycemia or oxygen in hypoxemia, or can be secondary to direct effects on the brain, such as an increase in intracranial pressure in herniation syndromes. The cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is dependent on the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the intracranial pressure (ICP). Therefore, as the ICP rises due to the mass occupying lesion (such as in intracranial hemorrhage or brain mass), the cerebral perfusion decreases unless the blood pressure is increased (CPP equals MAP minus ICP). The resultant decrease of CPP results in coma.

Additionally, malignant arrhythmias or hypotension can decrease the MAP enough to decrease perfusion to the brain. Remember that cardiac output equals stroke volume times heart rate, and changes in the rate or the stroke volume can reduce the cardiac output enough to alter the MAP. [1][3][4]

History and Physical

When eliciting a history from a patient who presents for altered mental status, it is important to obtain information both from the patient and from collateral sources (e.g., parents, children, friends, emergency management services, bystanders, the patient’s primary physician). This information can provide more insight regarding the chronicity of the change, precipitating factors, exacerbating or relieving factors, and recent as well as chronic medical history.

It is important to obtain detailed medication history, including over the counter and herbal supplements, to rule out drug interaction as a cause of altered mental status. Similarly, a history of illicit substance use (e.g., nicotine-containing products, alcohol, drugs such as heroin, marijuana, cocaine, club drugs like 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)), including frequency of use, typical dose, and last use.

When performing a physical exam, start with a primary survey (assessing the patient’s airway, spontaneous respirations, pulses and heart rate, the level of consciousness). Make sure to expose the patient and check their back and extremities for signs of trauma (ecchymosis, deformities, lacerations) or infection (cellulitis, rashes). Then, perform a secondary survey, with careful attention to the pupillary and neurologic exam.

Consider using a diagnostic tool for evaluation of mental status, such as the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE), the Quick Confusion Scale, or the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) [2][5][6].

Evaluation

Initially, evaluate the airway, breathing, and circulation, and stabilize as necessary. If the patient has a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of less than 8, no gag reflex, or other concerns for an ability to protect their airway, perform rapid sequence intubation. Similarly, if heart rate or blood pressure is slow enough to decrease CPP, consider external pacing, defibrillation, or vasopressors, as indicated.

At the bedside, check vital signs, ECG rhythm, and glucose. Consider empiric administration of a “coma cocktail” - naloxone for opiate overdose, dextrose for hypoglycemia, and thiamine for Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome or beriberi.

If the history or physical is suggestive of trauma, consider cervical spine immobilization. If there are signs of impending herniation (e.g., Cushing reflex or a unilateral blown pupil), elevate the head of the bed to 30 degrees, increase the respiratory rate, and consider mannitol and neurosurgical decompression. If there are no signs of impending herniation, consider head CT and appropriate neurosurgical consultation for any lesions identified on CT.

If the patient has signs concerning for infectious sources, give antibiotics, appropriate weight-based fluid boluses, and consider pulse dose steroids in the steroid-dependent.

If there are no signs of trauma and no suspicion for infection, consider toxic or metabolic causes, including medication overdose, withdrawal states, or the effects of drug-drug interaction.

Consider lab evaluation of serum electrolytes, hepatic, and renal function, urinalysis. Consider imaging with a chest x-ray to rule out pneumonia as a cause of altered mental status and/or head CT for concern of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). If none of these explain the cause of altered mental status, consider an evaluation of thyroid function, serum B12 levels, syphilis status. Additionally, lumbar puncture can be performed to rule out meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of altered mental status is targeted at the underlying cause, including symptomatic management, like intubation or external pacing for abnormal respiration or cardiac output, antibiotics and volume resuscitation for sepsis or septic shock, glucose for hypoglycemia, or neurosurgical intervention for intracranial hemorrhage.

In the delirious patient, consider environmental manipulation, such as lightning, psychosocial support, minimization of unnecessary noise, and mobilization to prevent worsening of sundowning behavior. If acute sedation is needed, consider haloperidol (5 mg to 10 mg by mouth, intramuscularly, or intravenously, but consider reduced dosing in the elderly). Most sources recommend against the chronic use of benzodiazepines in the elderly, as it can often worsen sundowning behavior due to the amnesiac and disinhibitory effects, but in the acute setting, treatment with benzodiazepines (typically lorazepam 1 mg to 2 mg by mouth, intramuscularly, or intravenously) can be useful.

For chronic maintenance of a patient with dementia with elements of sundowning, consider donepezil (5 mg/day) or atypical antipsychotics (mostly commonly risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine)[7][8].

Differential Diagnosis

- Intracerebral haemorrhage

- Large hemispheric strokes

Pearls and Other Issues

Consider patient safety at home when deciding if inpatient evaluation is appropriate.

Be cautious with special evaluation populations, especially the elderly who may have possible drug-drug interactions or infections, and immunocompromised individuals, for example, those with HIV/AIDS, those receiving chemotherapy, or those who are immunosuppressed as part of therapy for transplant or chronic medical illness.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with a change in mental status are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a neurologist, internist, psychiatrist, a radiologist, and an emergency department physician. Because there are numerous causes of mental status changes, a thorough history is necessary. While the patient is being worked up, the patient with acute mental status changes needs to be monitored by a nurse. The nursing staff should update the team about changes in the condition of the patient. The pharmacist should have a list of patient medications that may alter mental status. Specialized toxicology pharmacists may be consulted. Close communication should be made with the other healthcare professionals so that no serious cause of mental status changes is missed. [9][10]