Continuing Education Activity

Mallory-Weiss syndrome is one of the common causes of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding and is characterized by the presence of longitudinal superficial mucosal lacerations (Mallory-Weiss tears). These tears occur primarily at the gastroesophageal junction and may extend proximally to involve the lower to mid-esophagus or distally to involve the proximal portion of the stomach. This activity reviews the etiology, pathogenesis, evaluation, and management of Mallory-Weiss syndrome and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Describe exam findings consistent with Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Outline the treatment and management options available for Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to improve outcomes for patients affected by Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Introduction

Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) is one of the common causes of acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, characterized by the presence of longitudinal superficial mucosal lacerations (Mallory-Weiss tears). These tears occur primarily at the gastroesophageal junction; they may extend proximally to involve the lower or even mid esophagus and at times extend distally to involve the proximal portion of the stomach.

Though Albers first reported lower esophageal ulceration in 1833, Kenneth Mallory and Soma Weiss in 1929, more accurately described this condition as lower esophageal lacerations (not ulcerations) happening to patients with repetitive forceful retching and vomiting following excessive alcohol intake.[1]

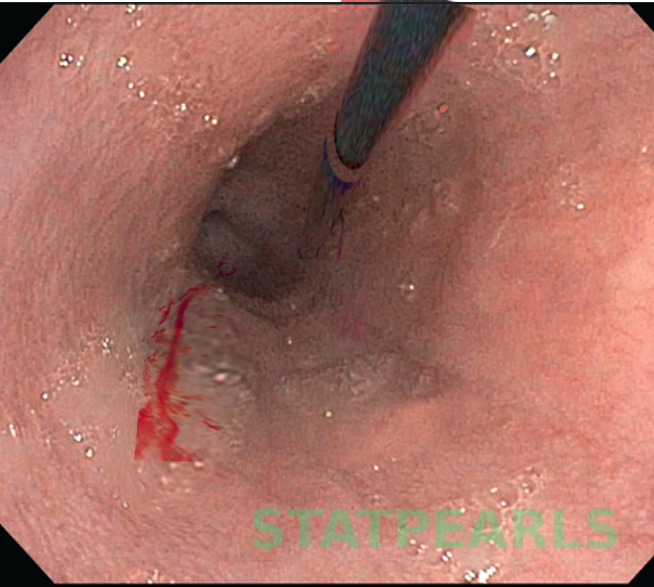

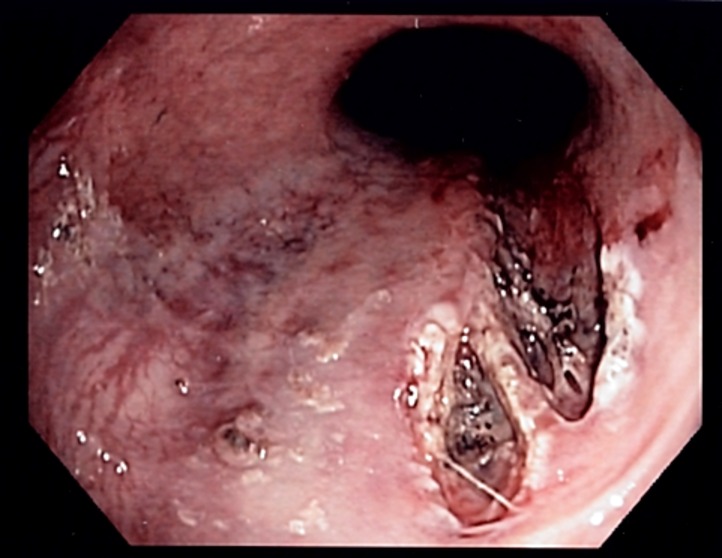

The diagnosis of MWS is usually confirmed with endoscopy. There is only a split of the mucosa near the GE junction. The average tear is about 2-4 cm in length and most patients have only one tear. the tear is just beneath the GE junction on the lesser curvature.

Etiology

Heavy alcohol ingestion is considered to be one of the most important predisposing factors as about 50% to 70% of the patients diagnosed with Mallory-Weiss syndrome have a history of the same.[2] The severity of the upper GI bleeding with Mallory-Weiss syndrome is also reported to be higher with the concurrent presence of portal hypertension as well as esophageal varices.

The relationship between a hiatal hernia (protrusion of an organ, usually the upper part of the stomach into the chest cavity through the esophageal opening of the diaphragm) and Mallory-Weiss syndrome is still a matter of debate. A hiatal hernia was found in a considerable number of cases with Mallory-Weiss syndrome, while a case-control study conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Florida found no difference in the incidence of a hiatal hernia between patients with Mallory-Weiss syndrome and the control group.[3]

Other risk factors include bulimia nervosa, hyperemesis gravidarum, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). All these conditions involve regurgitation of gastric contents into the esophagus. However, in a considerable number of patients (around 25% of cases), none of those mentioned above risk factors were identified.

The condition is precipitated by repeated acts of a sudden increase of the intraabdominal pressure such as retching, vomiting, straining, coughing, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), or blunt abdominal traumas.

Iatrogenic Mallory-Weiss syndrome is generally uncommon. However, it can occur as a complication of invasive procedures like upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE).[4] Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy procedure as such has only 0.07% to 0.49% complication rates to develop Mallory-Weiss syndrome, and hence the risk is low.

Epidemiology

MWS accounts for 1% to 15% of the causes of upper GI bleeding in adults and less than 5% in children in the United States. The age of highest incidence is between 40 and 60 years.[5] Males are 2 to 4 times more likely to develop Mallory-Weiss syndrome than women for unclear reasons. Hyperemesis being a frequent etiology for Mallory-Weiss syndrome in young women, pregnancy testing should be considered in such patients.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism by which Mallory-Weiss tears occur is still unknown. The suggested theory is that when the intraabdominal pressure suddenly and severely increases (as in cases of forceful retching and vomiting), the gastric contents rush proximally under pressure into the esophagus. This excess pressure from the gastric contents results in longitudinal mucosal tears which may reach deep into the submucosal arteries and veins, resulting in upper GI bleeding. These tears tend to be longitudinal, and not circumferential, possibly because of the cylindrical shape of the esophagus and stomach.[6]

History and Physical

The condition may be asymptomatic in mild cases. In 85% of cases, the presenting symptom is hematemesis. The amount of blood is variable; ranging from blood-streaked mucus to massive bright red bleeding.

In case of severe bleeding, other symptoms such as melena, dizziness, or syncope can be manifested. Epigastric pain is usually present and denotes the presence of a predisposing factor such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

There are no physical signs specific to Mallory-Weiss syndrome, and the signs are similar to any other hemorrhagic conditions or shock. During a physical examination, clinicians must check signs of severe bleeding and shock, including but not limited to, tachycardia, thready pulse, hypotension, dehydration, reduced skin turgor, and capillary filling time and intervene immediately if they are present. The rectal examination could show signs of melena.

Evaluation

At presentation, all patients with hematemesis should receive immediate attention and care as appropriate. After obtaining a history and performing the physical examination, they should be triaged by the severity of bleeding. Some patients might have significant internal bleeding, and hence, proper history and examination for signs of shock are vital. Lab tests include complete blood count (CBC), hemoglobin and hematocrit, coagulation profile (bleeding time, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count). Chronic alcoholism results in low platelet count.

The lab tests should also include kidney functions to recognize the presence of renal failure by measuring blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine. The presence of renal failure would be most likely from pre-renal azotemia unless the patient had previous coexisting chronic kidney disease. Ruling out myocardial ischemia or infarction by measuring cardiac enzymes and performing a bedside electrocardiogram (ECG) is also essential.

Upper GI endoscopy is the gold standard for definitively diagnosing Mallory Weiss tears, and managing simple active esophageal bleeding. It may demonstrate active bleeding, a clot, or a fibrin crust over the tear. In most cases, a single linear tear found in the proximal part of the lesser curvature of the stomach just below the cardia, confirms the diagnosis. Upper GI endoscopy is also useful in discovering other causes of bleeding including esophageal varices, gastric or duodenal ulcers among others. Most Mallory Weiss tears measure about an inch in length.

Barium studies should be avoided due to their low diagnostic value and their interference with the endoscopic diagnosis.

Angiography is indicated in actively bleeding tears in case of failure or inaccessibility of endoscopy to locate the site of the bleeding tear and to stop the bleeding.

Treatment / Management

Since Mallory-Weiss syndrome is mostly self-limited and recurrence is uncommon, the initial management aims at stabilizing the general condition of the patient, and a conservative approach would be appropriate in most of the patients.

Immediate resuscitation of patients with active bleeding should be started at the time of admission. We assess hemodynamic stability by checking airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC protocol). Establishment of a good central or peripheral intravenous (IV) access (usually 2 lines) along with fluid replacement could be life-saving in patients with severe bleeding. Packed RBCs infusion is indicated if the hemoglobin level is less than 8 gm/dl or if the patient presents with signs of shock or severe bleeding.

Nasogastric decompression using nasogastric tube could be performed, especially in patients suspected to have concomitant esophageal varices, before gastric lavage. Electrolyte imbalance, if present, should be corrected appropriately. Coagulation factors need to be optimized before proceeding with endoscopy. Most patients managed conservatively are typically hospitalized until hemostasis is achieved and symptoms are resolved.

Pharmacological Treatment

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers are given to decrease gastric acidity as increased acidity hinders the recovery of gastric and esophageal mucosa. Intravenous PPIs are given initially to patients who are expected to undergo endoscopic examination. Anti-emetics such as promethazine and ondansetron are given to control nausea and vomiting.

Endoscopic Treatment

Esophagogastroscopy is the investigation of choice in all cases of upper GI bleeding.[7] If bleeding had already stopped at the time of endoscopy, no further intervention is generally needed. In situations with ongoing active or recurrent bleeding, there are different modalities of endoscopic treatment. Epinephrine local injection (1:10,000 to 1:20,000 dilution) stops the bleeding through vasoconstriction.[8][9] Multipolar electrocoagulation (MPEC), injection of a sclerosant agent, Argon plasma coagulation (APC), or endoscopic band ligation are other options in such situations.

Angiotherapy

Angiography with either injection of a vasoconstricting agent such as vasopressin or transcatheter embolization with gel foam to obliterate the left gastric or superior mesenteric artery is considered when endoscopy is not available or has failed.[10]

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is rarely necessary and is deemed necessary after the failure of endoscopic procedures or angiotherapy to stop the bleeding. Laparoscopic over-sewing of the tear under endoscopic guidance has been performed with excellent results.[11]

Sengstaken-Blakemore tube compression is the last resort in the treatment of a bleeding Mallory-Weiss tear in debilitated patients.[5] It is the least preferable option since the bleeding is mostly arterial and the pressure in the balloon is not enough to overcome the pressure in the bleeding artery.

Differential Diagnosis

Mallory Weiss syndrome should be differentiated from other causes of upper GI bleeding;

- Boerhaave syndrome: A severe condition that shares the same predisposing factors with Mallory-Weiss syndrome, but the pathology is perforation of the esophagus

- Peptic ulcer: A peptic ulcer is the most frequent cause of upper GI bleeding. It has its characteristic clinical picture and is diagnosed definitively by endoscopy.

- Esophageal or gastric neoplasm

- Esophageal varices: Dilated tortuous vessels around the lower esophagus, mostly as a complication of portal hypertension. Esophageal varices may also coexist with Mallory Weiss syndrome.

- Arteriovenous malformations

Prognosis

For most patients, the outcomes are good. Bleeding usually stops spontaneously in most patients and the tear usually heals within 72 hours. The degree of blood loss does vary but blood transfusion is not common.

Complications

Complications are related to the degree of blood loss, such as hypovolemic shock, metabolic disturbance, and myocardial infarction.[12] Death occurs if the bleeding is not controlled. Esophageal perforation and recurrence in Mallory Weiss syndrome are rare complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although the condition is not very common, patients should be aware of the hazards of excessive alcohol drinking that include Mallory Weiss tears. It is important to counsel patients with previous episodes of hematemesis to avoid the precipitating factors that lead to esophageal tearing despite the rarity of recurrence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Mallory Weiss tear is not a rare presentation and its diagnosis can be difficult without endoscopy. The condition may be frightening because of the blood but most patients only need conservative care.

Collaboration and effective communication with the other supporting healthcare teams are crucial to ensure excellent patient service. Gastroenterology, interventional radiology and surgery consultations should be appropriately obtained when necessary to provide the best treatment options and to ensure hemodynamical stability. The best approach that will lead to the most favorable outcome includes a coordinated an interprofessional team made up of nurses, primary care, and specialists. Nurses should closely monitor these patients as some may develop hypotension, ongoing bleeding, and shock. Aggressive hydration is the key. The patients need to be closely monitored because in rare cases there may be perforation of the stomach, which does require surgical intervention. Close communication between the team members is vital to ensure improved outcomes.

The condition is generally very self-limited, and around 90% of the cases require only conservative management.[5] Healing of the tears occurs spontaneously with conservative treatment within 48 to 72 hours. Recurrence is very unlikely. Mortality from Mallory Weiss syndrome has significantly decreased due to the recent advances in the management of acute hemorrhage and shock.