Continuing Education Activity

Lymphadenopathy refers to the swelling of lymph nodes which can be secondary to bacterial, viral, or fungal infections, autoimmune disease, and malignancy. This activity outlines the evaluation and treatment of lymphadenopathy and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Summarize the etiology of lymphadenopathy.

Outline the typical presentation in lymphadenopathy.

Explain the management of lymphadenopathy.

Introduction

The lymphatic system is a complex component of the immune system involved in filtering substances in the body. Lymphocytes are the integral agents involved in searching for target proteins and travel through lymph nodes, which are diffusely placed throughout the body. Lymphadenopathy is a term that refers to the swelling of lymph nodes. Lymph nodes are small glands that are responsible for filtering fluid from the lymphatic system. They are divided into sections known as follicles, which are subdivided into B zones and T zones, which represent the base location of lymphocytic maturation.

Abnormal proliferation of lymphocytes may be a result of inflammation, infection, or malignancy, and thus, clinicians must perform a detailed history and physical to screen for lymphadenopathy. When inspecting for lymphadenopathy, one should carefully examine all pertinent anatomic regions, including the neck, supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal regions. In general, the size of a normal lymph node in the adult population should be less than 1 cm; however, there are exceptions to this rule.[1]

Etiology

Lymphadenopathy, while pertinent, may be nonspecific. There are several potential causes of lymphadenopathy, ranging from infectious, autoimmune, malignant, and lymphoproliferative.

There is a wide range of infectious etiologies, including bacterial, fungal, viral, mycobacterial, spirochetal, and protozoal organisms. Autoimmune disorders that may contribute include but are not limited to sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Malignant diseases like lymphoma, leukemia, metastatic cancer, and head and neck cancers are also common causes of lymphadenopathy. Lymphoproliferative disorders such as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis can also manifest with the enlargement of lymph nodes.

Lymphadenopathy can be localized or diffuse. About 75% of most lymphadenopathies are localized, and about 50% of those occur in the head and neck regions. Generalized lymphadenopathy, which involves two or more non-contiguous regions, is reported to occur in 25% of lymphadenopathies.[2]

Elucidating the etiology of lymphadenopathy can be challenging. A thorough history and physical exam are one of the most important steps in determining the underlying cause of lymphadenopathy.

Etiologies can be determined based on lymph node groups. Submental and submandibular lymphadenopathy commonly is infectious in origin, often presenting with viral prodromes. Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy can arise from localized bacterial and viral infections, as well as lymphoma.[2] Axillary lymphadenopathy can also be related to lymphoma or breast malignancy but can be involved by infections such as cat-scratch disease. Lastly, inguinal lymphadenopathy can be impacted by local sexually transmitted infections, lymphoma, and pelvic malignancies.

Epidemiology

A majority of patients with lymphadenopathy will have a benign etiology. Age is an important factor in characterizing the epidemiology of lymphadenopathy, and thus, can be divided into children and adults.

Children more commonly appear to have benign causes of lymphadenopathy. To better understand this, a study completed by Knight PJ et al. reviewed 239 children who underwent a peripheral node biopsy and found that the most common etiology noted was reactive hyperplasia of unknown etiology, followed by granulomatous infections, cancer, and dermatopathic lymphadenopathy.[3]

Adults also appear to have a low prevalence of malignancy. To further characterize this, a study was completed in a family practice setting where only 3% of 249 patients with lymphadenopathy underwent biopsies. Of these patients, no one was found to have a debilitating illness.[4]

A Dutch study also revealed that of 2556 patients that presented with unclear lymphadenopathy to their family physicians, 10% were referred for a biopsy, and only 1.1% were found to be related to malignancy.

These findings are mirrored by two case series completed in family practice departments within the United States that demonstrated that 0 of 80 patients and 3 of 238 patients had malignant causes of lymphadenopathy, respectively.

It is important to remember that endemic regions such as South Africa or India have increased rates of lymphadenopathy due to tuberculosis, parasitic infections, and HIV.[2]

Pathophysiology

Lymph nodes are a part of the reticuloendothelial system, which includes monocytes of the blood, macrophages of the connective tissue, thymus, spleen, bone marrow, bone, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue of visceral organs, lymphatic vessels, and lymphatic fluid found in interstitial fluid.[1]

Lymphatic fluid moves throughout the lymphatic system, transitioning from the organs to lymphoid capillaries, lymphatic vessels, and finally lymph nodes for foreign antigen filtration. Foreign substances are presented to the lymphoid cells, which lead to cellular proliferation and enlargement. Under microscopy, cellular proliferation in lymphoid follicles may be identified as several mitotic figures.[5] As lymphatic capsules stretch due to increased activity, patients may experience localized tenderness.

The development of B-cells originates from pluripotent stem cells from the bone marrow. B cells that successfully build their immunoglobulin heavy chains migrate to the germinal centers to allow for antibody diversification by somatic hypermutation.[6] B-cell lymphomas are believed to be a result of alternations in somatic hypermutation and chromosomal translocations.

The development of T-cells also begins from pluripotent stem cells, which mature within the thymic cortex.[7] While in the thymic cortex, T cells begin specific rearrangements at the T-cell receptor. It is understood that chromosomal translocations at the level of T-cell receptors lead to T-cell lymphomagenesis.

Lymph nodes follicle necrosis may occur as a result of many different conditions, be it inflammatory, infectious, or malignant. The predominance of neutrophilic infiltrates suggests bacterial infection, while lymphocytic predominance may suggest viral infection. However, clinicians must remember that etiologies may vary; lymphomas, leukemias, tuberculosis, or even systemic lupus may be more appropriate diagnoses in the appropriate clinical context.[8]

Histopathology

Histology of lymph nodes can vary when there are endogenous insults. Histology can provide further information regarding the cause of lymphadenopathy when etiology is not clear during initial history taking, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation.

Below is a list of common causes of lymphadenopathy with associated histological findings:

- Bacterial lymphadenitis: Predominately neutrophilic infiltrate can be found within the sinus and medullary cords. Follicular hyperplasia can be seen as well.[9][10]

- Viral lymphadenopathy: Infiltration by macrophages and lymphoid hyperplasia. Necrosis can be seen in those who are immunocompromised.[11]

- Sarcoidosis: Non-caseating granulomas that replace the normal architecture of the lymph node

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: There is partial or widespread loss of the lymph node by a single cell lineage. Lymphoid cells can either proliferate in a disorderly manner or as those that mimic follicular center structures.

- Hodgkin lymphoma: Can be classified by the histological appearance noted below. These histological types are listed in order of most common to least.[12]

- Nodular-sclerosing

- Mixed cellularity

- Lymphocyte-rich

- Lymphocyte-depleted

History and Physical

A history and physical must be completed in a systematic form. One must always remember all components of a complete history and physical examination.

History involves the following:

1. History of Presenting Illness: location, pain - if so intensity, quality, onset, precipitating factors, alleviating factors

2. Review of Systems: This should include a system-based review of all organ systems, including constitutional systems (fever, chills, night sweats, changes in weight, fatigue).

3. Past Medical History: It is imperative to know the patient's previous medical history, as this could clue into the reason for lymphadenopathy (i.e., HIV/AIDs, remote history of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma)

4. Medications: Some medications can cause reversible lymphadenopathy (i.e., cephalosporins, phenytoin [13])

5. Social History: It is vital to know living conditions, chemical exposures, use of alcohol, tobacco, recreational drugs, pets, animal exposures, recent travel

6. Sexual History: It is pertinent to know the number of sexual partners, sexually active with males, females, or both; use of protection, history of sexually transmitted infections, and partners with known sexually transmitted infections

7. Surgical History: Inquire about which surgeries and when they occurred, how soon the lymphadenopathy occurred (i.e., post-operative lymphadenopathy)

8. Family History: It is imperative to know if a family history exists of cancer

Physical examination involves the following:

1. Vital signs: Temperature, Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation are all of significance to help determine if the patient is hemodynamically stable. This can help differentiate sepsis from benign conditions.

2. A head-to-toe exam must to conducted including inspection of the head, ears, nose, throat, and thyroid gland. Auscultation of lungs, heart, and palpation for splenomegaly and hepatomegaly. A thorough inspection should be done of the skin, palpating when necessary, looking for rashes, lesions, nodules.

3. When palpating lymphadenopathy, one must keep in mind location, size, firmness, and pain.

- Location:

- Anterior cervical lymph nodes are superior and inferior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Posterior cervical lymph nodes are posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

- One should also inspect for supraclavicular, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy bilaterally.

- Local lymphadenopathy suggests a more localized disease as compared to widespread lymphadenopathy.[1]

- Size:

- Cervical lymph nodes and axillary nodes are atypical if > 1 cm, as compared to supraclavicular > 0.5 cm, and inguinal nodes >1.5 cm.

- Firmness:

- Generally, if a lymph node is readily mobile, it is less concerning for a malignant condition.

- Pain:

- Pain can be a sign of inflammation, an acute reaction to an infection, and is less concerning for a malignant process.

Evaluation

Listed below is a diagnostic approach that may help clinicians evaluate lymphadenopathy:

1. Laboratory evaluation: blood chemistries including complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic panel, lactate dehydrogenase, fungal serologies (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis), laboratory evaluation of Syphilis, HIV, CMV, EBV, HSV, HBV, QuantiFERON for tuberculosis.

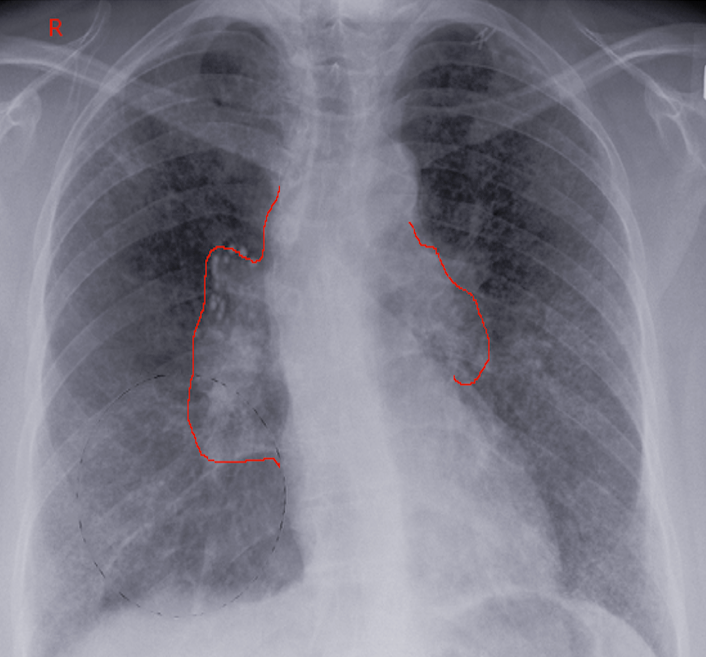

2. Imaging: Computed Tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis can be used to further substantiate the location of lymphadenopathy, pattern, and size. This can also guide a biopsy if needed.[14]

3. Lymph node biopsy: The need for a lymph node biopsy depends on the etiology of lymphadenopathy. An excisional node biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis.[15]

Treatment / Management

Treatment differs depending on the etiology of lymphadenopathy. Simply put, the following generalizations can be made:

1. Malignant: Surgery +/- radiation therapy +/- chemotherapy.

2. Autoimmune: Immune therapy, systemic glucocorticoids.

3. Infectious: Antibiotic therapy, antiviral therapy, or antifungal therapy.

4. Medication: Discontinuation of medication with re-evaluation is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

The variability in causes of lymphadenopathy can often present diagnostic challenges to clinicians. To reduce confusion and to improve diagnostic accuracy, it is important to obtain a thorough history and physical, create a set of differentials, and organize them in accordance with their presentation.

Causes of lymphadenopathy include but are not limited to:[2]

- Malignant: If the history and physical examination are consistent, lymphadenopathy may be concerning for diagnoses like metastatic breast cancer, Kaposi sarcoma, leukemias, lymphomas, metastatic disease (i.e., gastric cancer), malignant disorders of the skin.

- Autoimmune: Several conditions that are characterized by a highly active immune system may result in lymph node abnormalities, including dermatomyositis, Kawasaki disease, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, Sjogren syndrome, Still disease, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Infectious: Many different infections can contribute to benign changes in the lymph nodes. Health care providers may consider several different subcategories of infection, including bacterial, viral, and other:

- Bacterial: brucellosis, cat-scratch disease, bacterial pharyngitis, syphilis, tuberculosis, tularemia, typhoid fever

- Viral: cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, herpes simplex, HIV, mononucleosis, rubella, viral pharyngitis.[16]

- Other: bubonic plague, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, toxoplasmosis

- Medications: Often, medical therapies may incite the benign growths of lymph nodes. These therapies include but are not limited to allopurinol, atenolol, captopril, carbamazepine, cephalosporins, gold, hydralazine, penicillin, phenytoin, primidone, pyrimethamine, quinidine, sulfonamides, and sulindac.[2]

The aforementioned causes may be subdivided into a mnemonic “MAIM,” which may help as a useful memory tool for recall of the vast amount of differentials that may contribute to lymphadenopathy. These differentials lead to changes in lymph node size and/or consistency and require further investigation with history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing.

Staging

Staging is a process in oncology that allows health care providers to determine the extent of disease burden from its primary locations.

It should be known that malignant lymphadenopathy can occur from both primary lymphomas or from metastatic cancer.

Most, but not all, cancers use the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging system. A tumor refers to the primary involvement by the neoplasm and the depth of involvement. Node describes the local lymph nodes that are involved by the disease process, and metastasis defines distant sites of involvement.

The staging of non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma is based on the Lugano classification, which is based on the Ann Arbor system.[17]

- Stage I: Lymphoma found in 1 lymph node or in only one lymphoid organ

- Stage II: Lymphoma is found in 2 or more groups of lymph nodes on the ipsilateral side of the diaphragm

- Stage II: Lymphoma involvement bilaterally in reference to the diaphragm

- Stage IV: Lymphoma has metastasized to one organ beyond the lymphatic system

Prognosis

Generally, lymph node enlargement in younger populations (for example, children) tends to be benign and usually related to infection. There are exceptions to the rule, particularly if the patient’s history and physical are concerning for chronic infection, malignancy, or autoimmune conditions. Other risk factors that may be poor prognostic indicators include but are not limited to advanced age, length of duration of lymphadenopathy (> 4 weeks is concerning), generalized lymphadenopathy, male sex, lack of resolution of node size, and systemic signs (such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly).[18]

Complications

While lymphadenopathy itself may not lend itself to complications, unaddressed lymphadenopathy may lead to worsening progression of an underlying condition, the most concerning of which is sepsis or metastatic cancer. For lymphadenopathy related to autoimmune disorders, progressive autoimmune disease may lead to cancer or dysfunctional immunity, which may lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education remains critical in mitigating concerning lymphadenopathy. Abating interactions with modifiable risk factors such as alcohol, environmental toxins, recreational drugs, and/or tobacco may significantly reduce the risks of malignant lymphadenopathy. Immunizations and safe sex practices may help reduce the risk of infectious lymphadenopathy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Health care providers like nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians all need to be cognizant of the significance of lymphadenopathy. Most cases of lymphadenopathy are nonspecific, and thus, the provider caring for a patient needs to be aware of these signs in addition to advising patients to monitor for any abnormal growths or any inconsistencies in regional lymph node sites.