Continuing Education Activity

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF) is an idiopathic granulomatous disease predominantly affecting facial skin. This unique dermatosis, often challenging to diagnose and manage, shares features with other granulomatous disorders, such as rosacea and sarcoidosis. Despite being uncommon and of unclear etiology, LMDF's clinical presentation and histopathological characteristics set it apart, posing complexities in treatment.

This activity covers the intricacies of LMDF, providing insights into its etiology, pathophysiology, and management. Learners can expect an in-depth exploration of LMDF, starting with its elusive etiology and immune-mediated mechanisms proposed in current literature. Clinical presentations, specifically symmetrical red-to-yellow-to-brown papules on the central face with potential eyelid involvement, are thoroughly discussed. Histopathological findings, including caseous necrosis within granulomas, will aid in distinguishing LMDF from other facial granulomatous disorders. Various treatment courses, their efficacy, and potential challenges are explored to equip learners with a comprehensive understanding.

A key focus of this course is recognizing the integral role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with LMDF. Dermatologists, pathologists, rheumatologists, and other healthcare professionals are crucial in the comprehensive care of individuals with this condition. This collaborative learning experience aims to prepare healthcare professionals for effective teamwork in addressing the challenges LMDF poses.

Objectives:

Identify the characteristic clinical features of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei for prompt and accurate diagnosis.

Evaluate the severity and progression of lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei through standardized assessment tools, guiding appropriate treatment adjustments.

Develop the differential diagnosis and features that distinguish lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei from other facial granulomatous disorders.

Facilitate seamless care coordination among healthcare professionals managing lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, ensuring a cohesive and patient-centered approach.

Introduction

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF) is primarily an idiopathic granulomatous disease affecting facial skin, particularly the eyelids.[1][2] Nosologically, this condition is on a spectrum of facial granulomatous dermatoses and shares overlapping features with rosacea and sarcoidosis; however, a differentiating feature is the presence of caseous necrosis (separating it from sarcoidosis) and the lack of photoaggravation and erythema (separating it from rosacea).[3] In most cases, this disorder resolves spontaneously within several years but can leave potentially disfiguring scarring.

The diagnosis was reportedly first noted in 1878 by Fox and colleagues.[4] The name derives from a historical association with tuberculosis based on its clinical and histopathologic appearance of granulomas. More recent authors have proposed adopting the term facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution instead of the entrenched LMDF. However, a name change has not appeared to be widely accepted.[5] Older terms for a similar facial granulomatous dermatosis include micropapular tuberculid, Lewandowsky eruption, and lupoid rosacea.[6] Acne agminata has been used to refer to similar lesions in the axilla. However, most authors consider LMDF a unique entity separate from other diagnoses.

Etiology

The etiology of LMDF is uncertain, and there are around 200 cases reported in the literature.[4] The earliest reports presumed that lesions of LMDF were related to tuberculosis based on similar clinicopathologic findings to other tuberculids. The term tuberculid was historically used for reactive conditions associated with tuberculosis, in which the infectious agent is present elsewhere and is not found in the skin lesions. However, LMDF does not arise in association with pulmonary tuberculosis and does not generally respond to anti-tuberculous medications, though they have been reportedly used in some cases. Tuberculin skin testing is often negative in these patients.[7] Moreover, investigations, including histochemical staining for mycobacteria and tissue cultures and polymerase chain reaction-based studies, have consistently failed to demonstrate evidence of M. tuberculosis organisms within the LMDF granulomas.[8][9] A possible relationship with an unknown non-tuberculous mycobacterium has not been completely excluded.[8] Other organisms, such as Cutibacterium acnes and Demodex species, have been thought to play a role, as they do have a role in the related diseases acne vulgaris and rosacea, although these connections are not entirely elucidated.[4]

Similar to other facial granulomatous eruptions, it is often postulated that initial immune-mediated damage to the hair follicle leads to its subsequent rupture and provokes an allergic or foreign body granulomatous response to keratin, sebum, or microbial components in the dermis.[10] This hypothesis is supported by observations that the granulomatous infiltrate is often centered around a follicular structure, which can sometimes be seen on serial histologic sectioning if not initially evident.[5] Whether altered antigenicity of the hair follicle or sebaceous gland structures with subsequent T-cell mediated destruction or other disruption of the pilosebaceous unit is the inciting event is unknown. A relationship with hormonal effects on the pilosebaceous unit, as seen in certain acneiform variants, has not been shown.[5]

Epidemiology

LMDF is uncommon, although precise incidence rates are unknown (approximately 200 cases have been reported).[4] LMDF can be seen across a wide range of ages, with the most common occurrence in young adults (the average age in one series was 33 years) and is rare in older adults, although there are cases of young children and older adults with the condition.[9] A clear gender predilection has not been established. However, in a retrospective review, the average age of women (43 years) was older than men (23 years), and all patients beyond their mid-30s were women; the lack of gender specificity is also thought to separate this condition from rosacea, which does show a gender predominance.[4][11]

Pathophysiology

Some have considered LMDF as a variant of granulomatous rosacea, whereas other authors make the case for LMDF as a distinct entity.[12] The different clinical manifestations of rosacea are thought to result from the same underlying inflammatory pathways, including abnormalities of the innate immune system and neurovascular aberrations.[13] However, these vascular abnormalities are not seen in patients with LMDF. Demodex folliculorum mites are often found in skin biopsies from patients with rosacea. These mites may play an etiologic role, but they have not been consistently observed in skin biopsies from patients with LMDF.[5][8]

The biopsies of some patients with LMDF have shown a ruptured follicular infundibular cyst in the histologic sections.[8] Using a polymerase chain reaction assay, one study of 9 patients with LMDF demonstrated higher levels of Cutibacterium acnes bacteria within granulomatous areas separated by microdissection compared with normal-appearing skin regions. The authors suggested that the presence of C. acnes in the dermis around a disrupted hair follicle, in combination with host factors, may play a role in pathogenesis.[14]

Histopathology

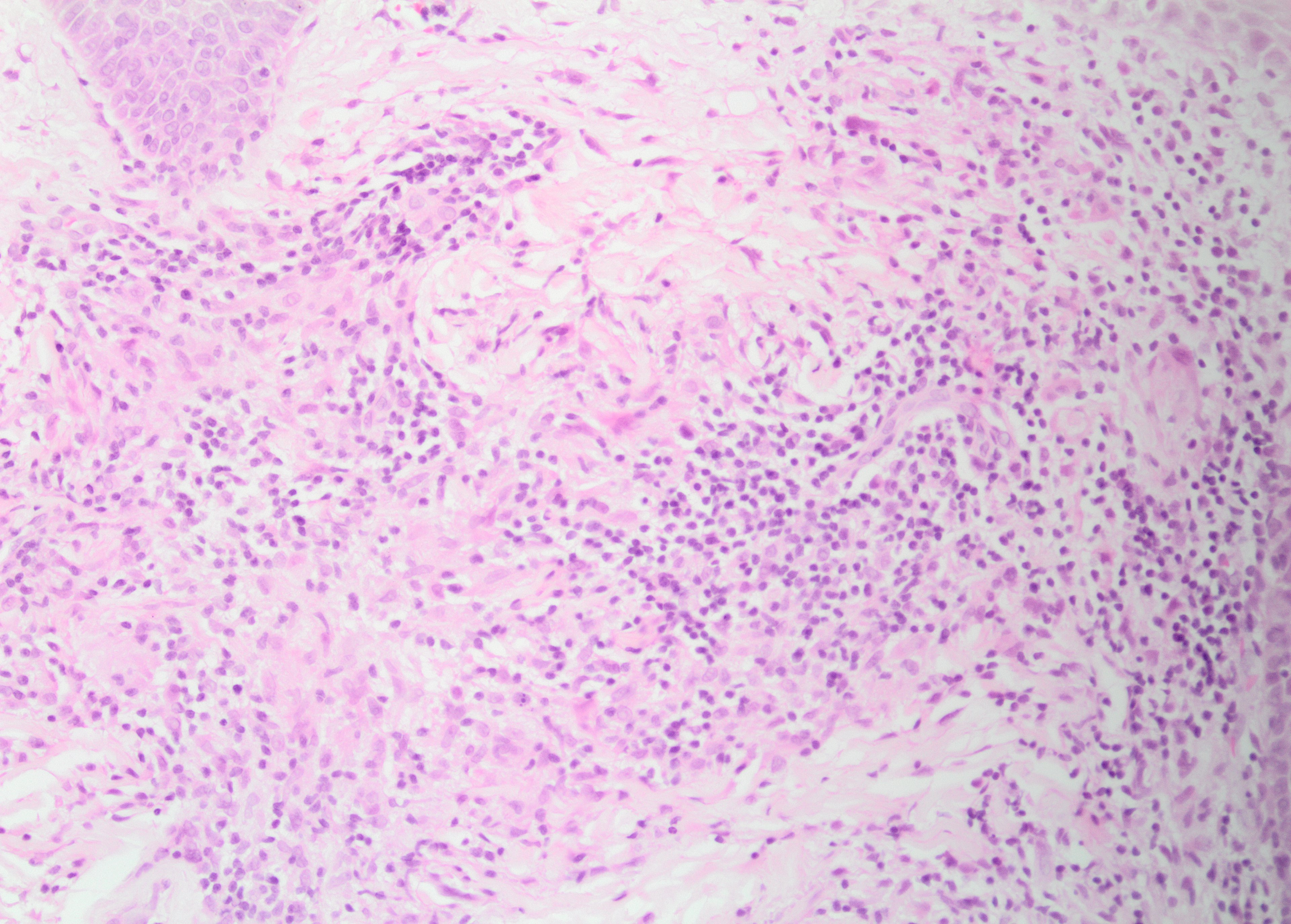

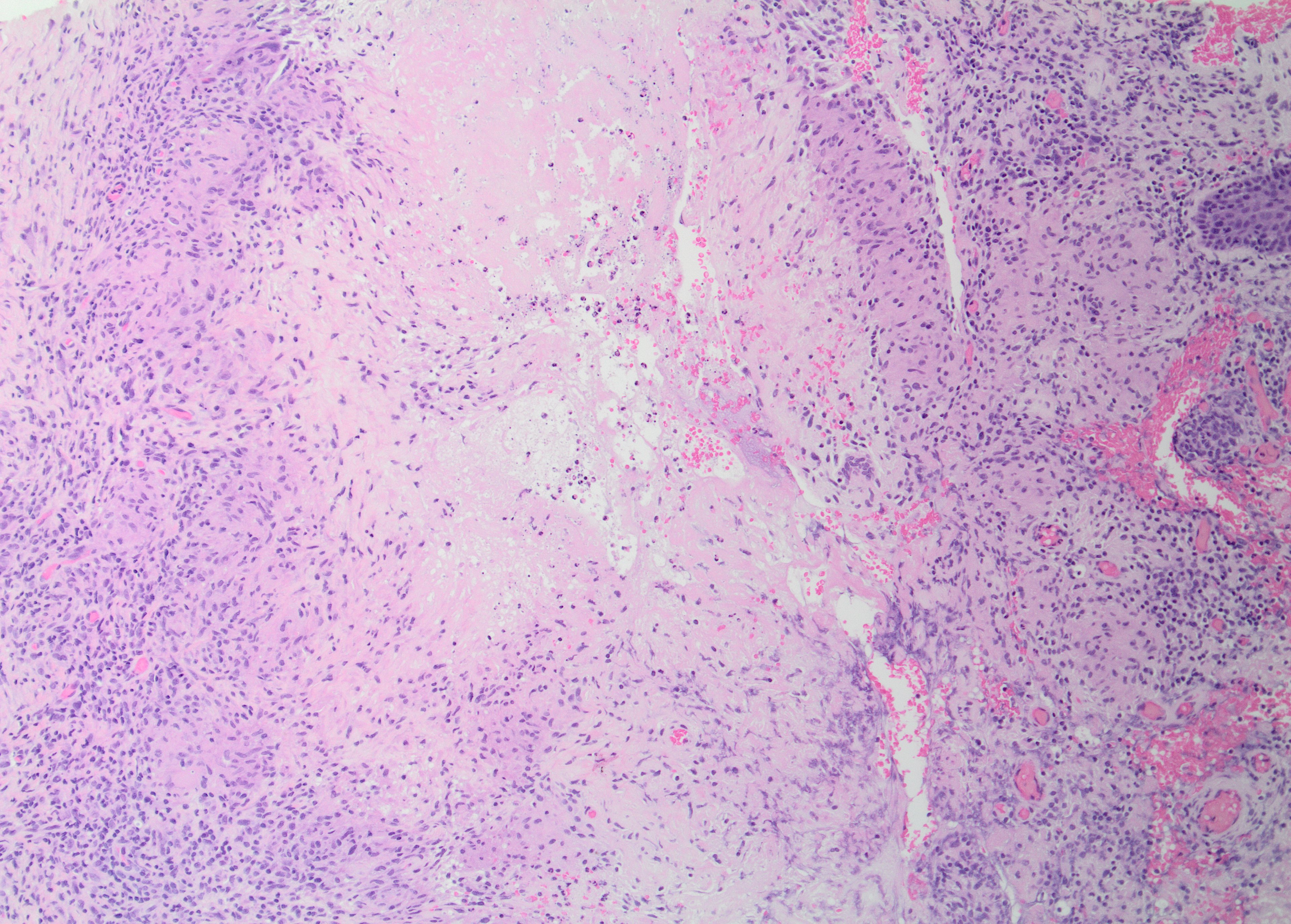

The histologic hallmark of LMDF is a granulomatous infiltrate, in some cases centered around hair follicle structures.[3] Both sarcoidal (non-caseating) and tuberculoid (with central caseation necrosis) granulomas have been observed (see Images. Granulomatous Inflammation Without Caseation and Caseating Granuloma), as have diffuse infiltrates of lymphocytes and histiocytes without well-formed granulomas.[15] The latter may be characteristic of early lesions and demonstrate a peri-adnexal pattern. Accompanying neutrophils with or without neutrophilic microabscesses have been variably observed, and some lymphocytic infiltrates may be observed.[4] Fibrosis is seen in late lesions, correlating with clinical scar formation.[4] Significant histologic overlap exists with granulomatous rosacea and other granulomatous disorders affecting the face.[5]

History and Physical

Patients often present with a relatively abrupt onset of asymptomatic discrete red, yellow, brown, or skin-colored papules or nodules, which are occasionally pustular and symmetrically distributed predominantly on facial skin; these often predominate in the central face and are follicular or nonfollicular.[16][4] The lower eyelids are most characteristically involved (see Image. Erythematous Papulonodules, Facial Eruption), and the forehead, cheeks, nose, upper lips, ears, chin, or neck involvement is common.[8] Extra-facial involvement is uncommon but has been reported in some cases, including on the trunk, extremities, and genital skin.[6] Co-morbidities have not generally been reported in association with LMDF.

Evaluation

Symmetrically distributed inflammatory papules or papulopustules with histologically confirmed granulomatous inflammation on biopsy of the affected tissue should lead to consideration of the diagnosis. A background of erythema, telangiectasias, or a propensity for flushing would favor a diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea, as would exacerbation of disease by such triggers as steroid use, sunlight, alcohol, or spicy foods.[5][9] Excluding an infectious etiology by histochemical stains (eg, Ziehl-Neelson stain) or tissue cultures is often prudent—although the sensitivity of these tests is imperfect. Many authors have included serum calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels in their workup, with or without chest x-ray and ophthalmologic exam, to help exclude sarcoidosis.[6] Serologic assays for tuberculosis and treponemal infection may also be considered.[8]

Treatment / Management

Monitoring the disease without medical therapy could result in spontaneous resolution in 12 to 24 months; however, this will likely involve significant scarring.[4] The evidence for treatment of LMDF is limited to case series and retrospective reviews and should be considered even though the disease course is usually self-limited. This disease tends to be poorly responsive to topical or systemic therapies that are first-line for granulomatous rosacea. The efficacy of oral tetracyclines is poor, whereas the response to isotretinoin is mixed.[12][15][17] In one series, patients responded better to oral prednisolone (administered at starting doses of 10 mg daily) or oral dapsone (100 mg daily).[5] Combining these 2 agents seemed especially effective in patients who had failed monotherapy with either alone. In the same series, combining oral dapsone with topical tacrolimus produced an excellent response in 7 of 7 patients.[5] Results from other studies also report good responses to systemic corticosteroids.[18] Other treatments could include clofazimine, anti-tuberculous medications, carbon dioxide laser with chemical peel, or topical tacrolimus in combination with a 1450 nm or 1565 nm nonablative laser.[4][19][20] Early, effective treatment may reduce the risk of significant scarring.

Differential Diagnosis

As previously discussed, cutaneous tuberculosis or other infections, especially fungal, mycobacterial, treponemal, or leishmanial, should be considered. A bilateral, symmetric, relatively rapid onset in an otherwise well patient without associated symptoms makes an infectious etiology less likely. If an infection is excluded, the clinical and pathologic differential may include granulomatous rosacea at one end of the spectrum and cutaneous sarcoid at the other.

Granulomatous variants of rosacea, like LMDF, can present with bilateral, symmetric facial papules with similar morphology. There is considerable histologic overlap, including a relationship to pilosebaceous units. However, LMDF may have larger granulomas that are more prone to caseation necrosis and are not expected to have actinic damage, vascular dilation, or the presence of Demodex mites.[9] The clinical features and course may help discriminate these entities. Notably, LMDF occurs without phymatous changes, ocular involvement, or vascular manifestations of rosacea, such as background erythema, flushing, or telangiectasia.[4] Compared to rosacea, LMDF tends to affect adults at a younger age, including some cases in adolescents and exceptional cases in children; this may affect men more commonly, though other studies note there may not be a gender disparity in LMDF compared with rosacea.[4][9] The involvement of eyelids, upper lips, and neck is more common in LMDF. Extra-facial involvement can also occur.[6] LMDF is more likely than rosacea to resolve spontaneously within several years but is more prone to significant pitted scarring. As discussed above, LMDF responds somewhat differently to treatment than rosacea, being less successfully treated with antibiotics and more successfully treated with corticosteroids.[5][6][8]

Sarcoidosis should be excluded by clinical or laboratory investigations, especially in those whose disease is slow to regress or shows progression.[10] While LMDF has also been proposed as a possible forme fruste of sarcoid, it lacks clinical, laboratory, or radiographic evidence of extracutaneous manifestations and does not progress to visceral involvement. Histologically, the granulomatous infiltrate of LMDF is more prone to caseation and is often associated with pilosebaceous units.[6] Deep-seated, annular, or solitary lesions, or lesions involving the scalp or only a part of the face, should raise concern for the possibility of sarcoidosis.[10]

Syringomas can also present on the eyelids and face, though these are sweat gland tumors and are thus histopathologically distinct from granulomatous facial dermatoses. Other facial granulomatous disorders may also be considered in the differential, including granulomatous perioral dermatitis, facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption, and other deep fungal infections; caseous necrosis may lead away from these diagnoses.[4][21][22]

Prognosis

LMDF is a skin-limited disease. The natural history of the disease is typically spontaneous involution over months to several years, with a mean duration of 18 months in one series.[11]

Complications

The primary long-term complication is facial scarring that can be significant and disfiguring. Early treatment may prevent or minimize considerable scarring.[5]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Unlike rosacea, there are no documented lifestyle risk factors for LMDF. Once the diagnosis is made after the appropriate workup as described above, patients should be reassured about the skin-limited nature of the disease, the expected eventual resolution, and the potential for treatment to reduce the risk of permanent scarring.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with LMDF benefit from management by an interprofessional team approach to improve outcomes. Primary care providers and dermatologists should be involved. Specific treatment options, including dapsone and systemic corticosteroids, require careful education and monitoring, which should be reinforced by and coordinated with nursing and pharmacy professionals.