[1]

Chaudhary P, Bhadana U, Singh RA, Ahuja A. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2015 Sep:41(9):1137-43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.04.022. Epub 2015 May 14

[PubMed PMID: 26008857]

[2]

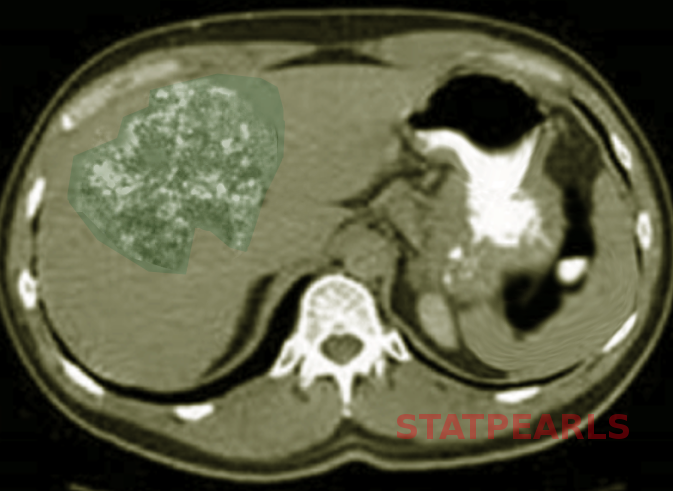

Yi LL, Zhang JX, Zhou SG, Wang J, Huang YQ, Li J, Yu X, Wang RN. CT and MRI studies of hepatic angiosarcoma. Clinical radiology. 2019 May:74(5):406.e1-406.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.12.013. Epub 2019 Jan 25

[PubMed PMID: 30686504]

[3]

Chien CY, Hwang CC, Yeh CN, Chen HY, Wu JT, Cheung CS, Lin CL, Yen CL, Wang WY, Chiang KC. Liver angiosarcoma, a rare liver malignancy, presented with intraabdominal bleeding due to rupture--a case report. World journal of surgical oncology. 2012 Jan 26:10():23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-23. Epub 2012 Jan 26

[PubMed PMID: 22280556]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Tripke V, Heinrich S, Huber T, Mittler J, Hoppe-Lotichius M, Straub BK, Lang H. Surgical therapy of primary hepatic angiosarcoma. BMC surgery. 2019 Jan 10:19(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12893-018-0465-5. Epub 2019 Jan 10

[PubMed PMID: 30630447]

[5]

Elliott P, Kleinschmidt I. Angiosarcoma of the liver in Great Britain in proximity to vinyl chloride sites. Occupational and environmental medicine. 1997 Jan:54(1):14-8

[PubMed PMID: 9072028]

[6]

Tran Minh M, Mazzola A, Perdigao F, Charlotte F, Rousseau G, Conti F. Primary hepatic angiosarcoma and liver transplantation: Radiological, surgical, histological findings and clinical outcome. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology. 2018 Feb:42(1):17-23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2017.02.006. Epub 2017 Apr 14

[PubMed PMID: 28416360]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[7]

Averbukh LD, Mavilia MG, Einstein MM. Hepatic Angiosarcoma: A Challenging Diagnosis. Cureus. 2018 Sep 11:10(9):e3283. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3283. Epub 2018 Sep 11

[PubMed PMID: 30443453]

[8]

Millan M, Delgado A, Caicedo LA, Arrunategui AM, Meneses CA, Villegas JI, Serrano O, Caicedo L, Duque M, Echeverri GJ. Liver Angiosarcoma: Rare tumour associated with a poor prognosis, literature review and case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2016:28():165-168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.09.044. Epub 2016 Sep 29

[PubMed PMID: 27718433]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Lee SW, Song CY, Gi YH, Kang SB, Kim YS, Nam SW, Lee DS, Kim JO. Hepatic angiosarcoma manifested as recurrent hemoperitoneum. World journal of gastroenterology. 2008 May 14:14(18):2935-8

[PubMed PMID: 18473427]

[10]

Tsunematsu S, Muto S, Oi H, Naka T, Kitagataya T, Sasaki R, Taya Y, Baba U, Tsukamoto Y, Uemura K, Kimura T, Ohara Y. Surgically Diagnosed Primary Hepatic Angiosarcoma. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2018 Mar 1:57(5):687-691. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9318-17. Epub 2017 Nov 20

[PubMed PMID: 29151516]

[11]

Kim HR, Rha SY, Cheon SH, Roh JK, Park YN, Yoo NC. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of advanced stage primary hepatic angiosarcoma. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2009 Apr:20(4):780-7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn702. Epub 2009 Jan 29

[PubMed PMID: 19179547]

[12]

Matsumoto M, Tamura M, Komiya T, Aridome G, Narita R, Hisaoka M, Ohtsuki M, Otsuji Y. Hepatic angiosarcoma: a rare liver tumor in a hemodialysis patient. Clinical nephrology. 2009 May:71(5):590-2

[PubMed PMID: 19473625]

[13]

Forbes A, Portmann B, Johnson P, Williams R. Hepatic sarcomas in adults: a review of 25 cases. Gut. 1987 Jun:28(6):668-74

[PubMed PMID: 3623214]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[14]

Huang NC, Kuo YC, Chiang JC, Hung SY, Wang HM, Hung YM, Chang YT, Wann SR, Chang HT, Wang JS, Ho SY, Guo HR. Hepatic angiosarcoma may have fair survival nowadays. Medicine. 2015 May:94(19):e816. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000816. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25984668]

[15]

Huang IH, Wu YY, Huang TC, Chang WK, Chen JH. Statistics and outlook of primary hepatic angiosarcoma based on clinical stage. Oncology letters. 2016 May:11(5):3218-3222

[PubMed PMID: 27123094]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence