Continuing Education Activity

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the central measure of left ventricular systolic function. LVEF is the fraction of chamber volume ejected in systole (stroke volume) in relation to the volume of the blood in the ventricle at the end of diastole (end-diastolic volume). Stroke volume is calculated as the difference between EDV and end-systolic volume (ESV). This activity reviews the calculation of LVEF, its clinical relevance and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with depressed LVEF.

Objectives:

- Identify the parameters required to calculate the left ventricular ejection fraction.

- Describe conditions associated with a depressed left ventricular ejection fraction.

- Recall the clinical relevance of knowing the pathophysiology of left ventricular ejection fraction.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance management of patients with a depressed LVEF and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the central measure of left ventricular systolic function. LVEF is the fraction of chamber volume ejected in systole (stroke volume) in relation to the volume of the blood in the ventricle at the end of diastole (end-diastolic volume). Stroke volume (SV) is calculated as the difference between end-diastolic volume (EDV) and end-systolic volume (ESV). LVEF is calculated from:

LVEF: [SV/EDV] x 100

Normal ranges for two-dimensional echocardiography obtained LVEF as per the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging are:

LVEF (%) among the male population:

- 52% to 72% normal range

- 41% to 51 mildly abnormal

- 30% to 40% moderately abnormal

- Less than 30% severely abnormal

LVEF (%) among the female population:

- 54% to 74% normal range

- 41% to 53 mildly abnormal

- 30% to 40% moderately abnormal

- Less than 30% severely abnormal

[SV: Stroke volume, EDV: End-diastolic volume][1]

The simplest classification as per the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that is used clinically as follows:

- Hyperdynamic = LVEF greater than 70%

- Normal = LVEF 50% to 70% (midpoint 60%)

- Mild dysfunction = LVEF 40% to 49% (midpoint 45%)

- Moderate dysfunction = LVEF 30% to 39% (midpoint 35%)

- Severe dysfunction = LVEF less than 30%

Documentation may be quantitative (ejection fraction value) or qualitative (eg, "moderate dysfunction" or visually estimated ejection fraction).

Qualitative results should correspond to the numeric equivalents as above.

Indications

The accurate measurement of LVEF is very important for managing patients with cardiovascular disease. LVEF also has a prognostic value in predicting adverse outcomes in patients with congestive heart failure, after myocardial infarction, and after revascularization.[2][3][4]

LVEF plays an important role in assessing the severity of a decrease in the systolic function of the heart and thus is helpful in directing the management of various cardiovascular diseases.

Indications for measuring LVEF include:

- Defining the anatomy and function of the left ventricle

- Assessing global and segmental left ventricular function: qualitative and quantitative

- Assessing patients with signs and symptoms suggestive of cardiovascular diseases

- Identifying the category of heart failure, i.e., heart failure with preserved (HFpEF) or reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)

- Ventricular arrhythmias to assess for structural etiology

- Planned or prior exposure to potentially cardiotoxic therapy

- Evaluation before a procedure for which left ventricular systolic function may be a risk factor or contraindication

- Assessing congenital heart disease

- Assessing valvular disorders

Technique or Treatment

LVEF can be calculated using various modalities, either subjectively by using visual estimation or objectively by quantitative methods. The preference is to employ quantitative measures to assess LVEF to minimize variability and favor more precision and accuracy in the measurement.

Non-invasive Assessment Modalities

- Echocardiography

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Computed tomography (CT)

- Gated equilibrium radionuclide angiography (multiple-gated acquisition [MUGA] scan)

- Gated myocardial perfusion imaging with either single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET)

Invasive Assessment Modalities

- Left ventricular contrast ventriculography during invasive catheterization

Echocardiography

Currently, various methods can be used to measure LVEF using echocardiography. The methods used differ from each other based on the type of echocardiographic image used (M-mode, two-dimensional, or three-dimensional) and the equations used to determine left ventricular (LV) volumes. The measurements obtained can be linear (one-dimensional), area (two-dimensional), or volume (three-dimensional) measurements. Lack of ionizing radiation works in favor of echocardiography. The biplane method of disks (modified Simpson’s rule) is the currently recommended two-dimensional method to assess LVEF. Other methods listed below which rely heavily on geometric assumptions (i.e., modified quinones, ellipsoid model, hemisphere-cylinder model) are no longer recommended in clinical practice for the estimation of LVEF.

M-mode and Two-dimensional Echocardiography

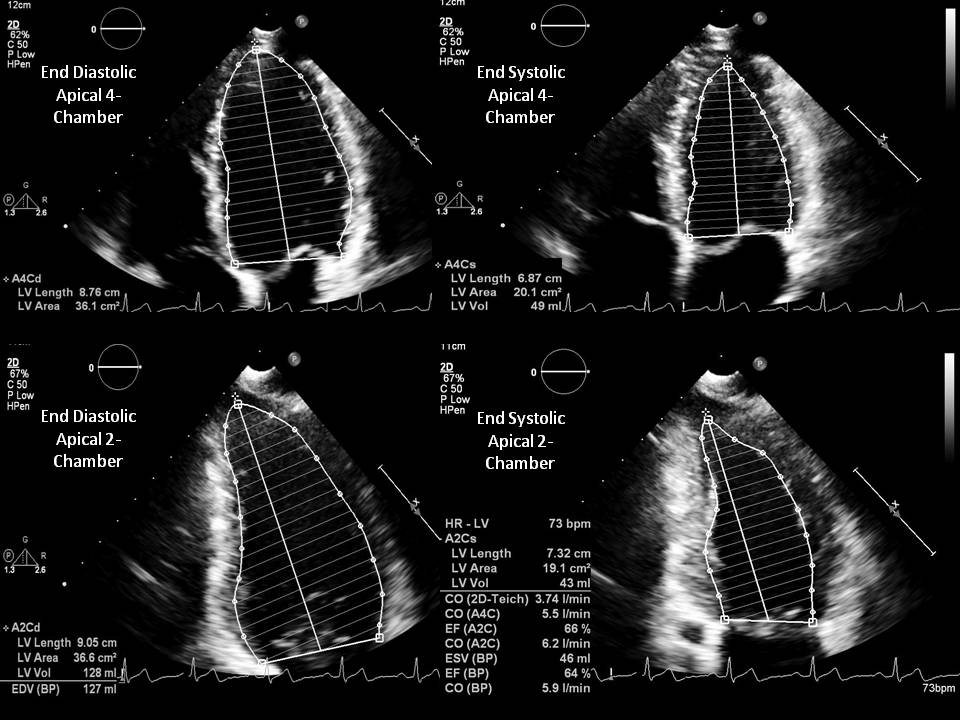

- Modified Simpson method (biplane method of disks) is a modality requiring area tracings of LV cavity. The American Society of Echocardiography recommends this method for measuring LVEF. This method requires the measurement of LVEF by tracing the endocardial border in both the apical four-chamber and two-chamber views in end-systole and end-diastole. These tracings eventually divide the LV cavity into a predetermined number of disks (usually 20). Disk volumes are based on the tracings obtained from the study. When compared to the modified Quinones method, fewer geometric assumptions of the LV shape are necessary. This modality directly measures the contribution of longitudinal contraction. Since the entire tracing of the LV cavity border is not done, some geometric assumptions need to be made.

- The modified Quinones method utilizes linear measurements. This method employs single measurements of the LV cavity in the mid-ventricle in both end-diastole and end-systole and can be employed using either M-mode or two-dimensional imaging. Volume calculations derived from linear measurements may be inaccurate because they rely on the assumption of a fixed geometric LV shape, such as a prolate ellipsoid, which does not apply in a variety of cardiac pathologies. Quinones method for calculating LV volumes from LV linear dimensions is no longer recommended for clinical use.

Algorithms from which Total LVEF, EDV, and ESV can be Calculated

- Modified Simpson’s rule: The left ventricle is considered the sum of a cylinder (from the base of the heart to the mitral valve), a truncated cone (from the level of the mitral valve to the level of the papillary muscles), and another cone attributed to the cardiac apex. These three sections were assumed to be of equal height.

- An ellipsoid model using biplane data: Two perpendicular echo planes (the mitral valve and apical view) were substituted for two angiographic projections. The apical plane minor (septal-posterolateral) axis is derived from the image area and its longest length. For this model, the mitral plan is assumed to midway between the base and apex. The mitral plane minor axis is derived from the area and the septal-posterolateral dimension of the mitral leave image.

- An ellipsoid model using single-plane data: Area and length from the apical echocardiographic image were substituted into the standard single=plane area-length equation.

- A hemisphere-cylinder model using biplane data: The cross-sectional area at the mitral valve level and long axis from the apical view were used to solve for the volume of a cylinder capped on one end by a hemisphere with a base area and height equal to that of the cylinder.

- A modified ellipsoid model using unidimensional data: The septal-posterior wall dimension was substituted into a formula described by Teichholz based upon an ellipsoid model where the major axis is a variable function derived from the measured minor axis, D. 2(7.0/2.4+D)D. This formula is meant to compensate for the deviation from the ellipsoid model seen in both unusually large and small ventricles. The Teichholz method for calculating LV volumes from LV linear dimensions is no longer recommended for clinical use.

Three-dimensional Echocardiography

Because three-dimensional echo does not require geometric assumptions, it is felt to be the optimal way of measuring LVEF using echocardiography. LVEF derived from this modality would mostly require the data to be obtained over several heartbeats using special three-dimensional imaging probes. Unlike other M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiographic techniques, three-dimensional methods give a minimal explanation about the shape of the LV cavity. Compared to other echocardiographic methods, three-dimensional modality is known to be more accurate and far less variable because the entire LV cavity is detected.

MRI

LVEF can be obtained with MRI using manual, semi-automated or automated methods. Simpson disk summation method uses the short-axis cine steady-state free precession images of the LV to obtain LVEF. During the end-systole and end-diastole phase, short-axis images are obtained. LV endocardial borders are manually traced on each short-axis image to obtain the ventricular cavity area for each slice. Multiplying the area of the tracing for each image slice by the slice interval (image gap + slice thickness) gives the volume of the slice. LV volume is then derived by the addition of the volumes of the slices. LV shape needs to be determined in this technique as the entire LV cavity is traced. A well-defined endocardial border can be obtained with the use of high contrast. Calculation of LVEF with MRI does not necessarily require the use of ionizing radiation or contrast material.

CT

Lack of contrast results in poor differentiation on non-contrast CT images. As a result, iodinated contrast is used, which helps in differentiating blood and endocardial borders. The automated methods are used, which depend on Hounsfield unit measurements. These measurements and contrast play an important role in differentiating the LV cavity from the endocardium. LVEF can be calculated using the Simpson method. This involves generating and tracing reconstructed short-axis cine images of the heart. Determining the LV shape is essential as this technique involves the tracing of the entire LV cavity using the Simpson method. The definition of the endocardial border is directly related to the timing of the contrast bolus. Unlike the MRI, CT images are obtained with single breath hold. However, one has to take into consideration the patient's poor renal function and contrast allergies while using the contrast material, which can limit the use of this modality.

Nuclear Cardiac Imaging

There are different techniques available to calculate LVEF. The two most commonly employed nuclear cardiac imaging modalities to calculate LVEF are gated equilibrium radionuclide angiography (multiple-gated acquisition [MUGA] scan) and gated myocardial perfusion imaging with either single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET) radionuclide angiography.

Radionuclide Angiography

This is a technique in which a patient's red blood cells are labeled with technetium 99m pertechnetate. Planar images of the left ventricle are obtained. However, SPECT images can also be obtained. Planar imaging to calculate LVEF calculation requires differentiation of left and right ventricle with left anterior oblique projection. LV region of interest is determined, following which the radioactivity counts within that region are analyzed. Analyzing radioactivity counts within that identified region is important as this technique studies the changes in radioactivity in the left ventricle between the end-systolic phase and end-diastolic phase instead of truly measuring volumes of the left ventricle. ECG guidance is used to gate image acquisition over multiple cardiac cycles. Each cardiac cycle is later separated into a predetermined number of intervals (16 or 32), relating to the number of frames (images) per cardiac cycle. Frame with the highest count represents the end-diastole, and frame with the lowest count represents the end-systole.

LVEF can be calculated from the following equation: Net counts in the end-diastolic frame - net counts in the end-systolic frame/net counts in end-diastole. Net counts are determined by subtracting counts from a background region of interest (next to the left ventricle) from measured LV counts. This technique can be performed especially in patients whose body habitus limits the use of other modalities. It can be used in the course of cardiotoxic chemotherapy and/or subsequent to radiation to the anterior or left chest when echocardiography has not been helpful. Radionuclide angiography is also recommended when echocardiography has proven inadequate (e.g., COPD, obesity) or in the presence of significant resting wall motion abnormalities or distorted geometry. There are no contraindications to this modality.[5]

Gated Myocardial Perfusion Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography and Positron Emission Tomography Technique

Radiolabelled myocardial perfusion agent such as technetium 99m-radiolabelled sestamibi or tetrofosmin is initially injected into a patient. Ammonia, rubidium, or fluorodeoxyglucose can be used as imaging agents. LVEF can be calculated along with a myocardial perfusion study. This helps in analyzing function and perfusion with one test. Imaging agents enter the myocardium once injected into the patient. ECG-gated images are obtained. The ECG gating helps in dividing the cardiac cycle into a pre-calculated number of frames (images) per each cycle (could be 8 or 16). Automated edge detection software plays an important role in analyzing reconstructed three-dimensional data to determine LVEF. This technique will require a three-dimensional data set as a result of which assumptions of the LV cavity need to be determined. The border between the high LV myocardium and the count poor LV cavity can be differentiated by the software used in the technique. EDV and ESV are the two important variables that can be obtained by calculating LV cavity volume during every cardiac cycle frame.

Left Ventricular Contrast Ventriculography During Invasive Catheterization

This technique requires a pigtail catheter to inject a contrast medium into the ventricular cavity. This position opacifies the cavity from the basal part up to the apex, does not hinder the mitral subvalvular apparatus, and causes little ventricular ectopic activity. Thirty degrees right oblique and 60 degrees left anterior oblique are the most commonly used views. The right anterior oblique view is cheaper and uses less radiation, and thus, is more commonly used. Various geometric methods have been developed that help in determining LVEF. These methods are based on determining ventricular volumes using mathematical models that assume that the ventricular cavity is symmetrical. Initially, ESV and EDV are calculated, which later help in determining the LVEF. The disk method (Simpson’s rule) and the Dodge-Sandler area-length method are the most commonly used mathematical methods. Dodge-Sandler area-length method is the most commonly used method because LV in the 30 degrees right anterior oblique view and 60 degrees left anterior oblique view resembles an ellipse. This makes the longitudinal axis of the ventricular cavity to coincide with the longitudinal axis of this shape. Ventricular volume is obtained by calculating the volume of the ellipsoid.

Clinical Significance

Left ventricular ejection fraction is a powerful predictor of cardiac mortality. In clinical practice, LVEF has become the primary criterion used for defibrillator placement. The MADIT II (Second Multicenter Automated Defibrillator Implantation) trial has demonstrated a significant reduction in sudden cardiac death and all-cause mortality after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator device (ICD) placement among patients with previous myocardial infarction and LVEF of less than 30%. LVEF now occupies a central position in guidelines for the use of ICD when recommended for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.[6][7][8][9]

Higher LVEFs were associated with a linear decrease in mortality up to an LVEF of 45% among heart failure patients. However, increases above 45% were not associated with further reductions in mortality. Although LVEF is a strong independent predictor of mortality in heart failure patients, the prognostic value of LVEF should be interpreted in the context of other established risk factors. Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend the routine assessment of LVEF in heart failure patients to guide therapy but fall short of defining a relationship between LVEF and prognosis.[10][11]

LVEF is an important parameter to monitor LV function in the course of cardiotoxic chemotherapy. Echocardiography is the method of choice for the evaluation of patients before, during, and after cancer therapy. LVEF<53% at baseline should prompt cardiology consultation to discuss the risk/benefit ratio. The integrated approach of LV function assessment also recommends measurements of global longitudinal strain and troponins. If during chemotherapy, LVEF decreases > 10% from baseline to a final LVEF below 53%, patients must be referred to the cardio-oncology unit to consider heart failure therapy and cancer treatment strategy reevaluation. [12]

In patients with valvular diseases, LVEF is also used as one of the criteria to determine management. Aortic valve replacement is recommended for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis or chronic severe aortic regurgitation and LVEF less than 50%. Mitral valve surgery is considered for asymptomatic patients with LVEF ≤ 60%.[13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with abnormal or depressed left ventricular function are best managed by an interprofessional team that includes primary care providers, cardiovascular nurses, dieticians, and pharmacists. The majority of these patients may have chronic heart failure or ischemic heart disease. The treatment varies depending on the cause, but a low ejection fraction correlates with a poor prognosis in many cases.