Introduction

Intrathecal therapy began to emerge in the late 1970s when the World Health Organization (WHO) placed attention on a more careful treatment of cancer pain. Later on, the interest in the use of intrathecal catheters for intrathecal administrations of drugs increased after the clinical demonstration of the efficacy of intrathecal morphine. In 1978, indeed, Wang et al. and later, Ventafridda et al. demonstrated that subarachnoid injections of morphine attenuated pain in patients with cancer.[1][2] The next step was the intrathecal administration of morphine through implantable reservoirs. The first to describe the use of an implantable pump for the administration of intrathecal drugs was Onofrio, in 1981, followed by several clinical cases and several clinical investigations.[3][4][5]

With proven efficacy, intrathecal therapy quickly came into use for the management of intractable pain for both cancer and non-cancerous pain.[6] An intrathecal catheter can also be used to prevent post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) following an accidental dural puncture during epidural anesthesia (e.g., in parturients).[7] Through this approach, the catheter can be used to provide analgesia (local anesthetics) and gets removed after at least 24 hours. Finally, since 1984, intrathecal therapy has also been used for severe spasticity in individuals affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), spinal cord injury (SCI), cerebral palsy (CP), and in patients with acquired brain injury (stroke). In the management of spasticity, baclofen is the recommended pharmacological treatment of choice.[8] Attempts have also been made to use intrathecal baclofen for the treatment of tetanus spasticity.[9]

In summary:

- The advantages of intrathecal therapy include better analgesia with fewer side effects and a lower dose of drugs administered as the drug is taken directly to the receptors with a good impact on severe spasticity in adults and children.

- The disadvantages include the risks associated with the procedure, infections, side effects of the drugs administered, and costs.

Anatomy and Physiology

The oral or parenteral administration of drugs is limited, mainly due to the shielding effect of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) on the macromolecules. In contrast, intrathecal therapy allows releasing drugs directly into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through which they reach the site of action such as the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thus eluding first-pass metabolism and the filter of the BBB. The CSF delivery involves a reduction in doses and, thanks to limited interaction with systemic receptors, reduces the potential occurrence of drug-induced adverse effects. In the case of opioids, these drugs act at the level of the dorsal horn; here, opioids interact with mu and delta (mainly) metabotropic G-protein coupled receptors in a presynaptic position between the primary and secondary neurons and on the body of the postsynaptic neuron. The activation of these receptors involves the inhibition of the release of substance P and other neurotransmitters. Again, the action on the postsynaptic neuron further enhances this inhibitory effect on the central transmission of the impulse that via the spinothalamic tract reaches the ventral posterolateral nucleus (VPL) of the thalamus. Opioid drugs also act directly on periaqueductal gray (PAG) in the midbrain, where there is a particular expression of opioid receptors. PAG plays a pivotal role in modulating pain through an influence on the descending path. In particular, PAG functionally connects to the serotoninergic raphe nuclei, which project to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This descending system interacts with inhibitory enkephalinergic interneurons into lamina II of the medullary gray matter (Rolando's gelatinous substance). In turn, the activation of these interneurons induces the release of the endogenous opioids enkephalin and dynorphin that bind to the mu-opioid receptors on the C and A-delta fiber axons that carry pain signals from peripheral nociceptors.

Indications

Indications for intrathecal therapy through a catheter are:

- Cancer pain. Treatment of refractory pain in patients with cancer and with inadequate pain relief due to ineffective analgesia with drugs administered in other ways, e.g., severe and intractable side effects from oral/transdermal opioids.

- Non-cancer pain conditions. Failure of interventional and surgical techniques such as failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), and lumbar post-laminectomy syndrome. Difficult to manage painful conditions, including complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and causalgia (CRPS type 2), phantom limb pain, plexopathy such as brachial plexopathy, and lumbosacral and radiation-induced plexopathy are other indications.

- Severe spasticity. Intrathecal baclofen is indicated for the management of spasticity in patients with serious side effects or with an unsuccessful response to the maximum doses of oral baclofen, tizanidine, and/or dantrolene.

Good circulation of CSF and informed consent are mandatory.

Pain Management

Persistent chronic pain is frequent in patients with cancer and has a severe impact on their health-related quality of life (HR-QOL). A recent systematic review found that 38% of patients with cancer rated their pain as moderate or severe. Furthermore, pain prevalence was 39.3% after curative treatment, 55% during anticancer therapies, and 66.4% in advanced, metastatic, or end-stage disease.[10] According to the WHO guidelines, pain management includes various treatments, pharmacological and non-pharmacological, or both combined. Pharmacological treatments vary on the type of pain. Management of neuropathic pain involves the use of different drugs such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, opioids, antiepileptic drugs (such as carbamazepine, gabapentin, and pregabalin), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), muscle relaxants, ketamine, local capsaicin, cannabinoids, used alone or more often, in combination. Undoubtedly, systemic opioids are the most commonly used agents, but many studies have shown that up to 80% of opioid-treated patients will have at least one side effect (mostly nausea, vomiting, constipation, respiratory failure) and, more importantly, effects such as dependence, tolerance, and immunosuppression. Again, efficacy is often limited in chronic pain conditions, especially those featuring neuropathic pain. Indeed, despite full compliance with the WHO analgesia guidelines, for many patients with cancer, pain control remains inadequate. For this reason, a multimodal and an interprofessional approach is needed to obtain the most effective but also the safest therapy.[11] In this context, the intrathecal route of drug delivery can be an effective option for the management of chronic refractory pain. By placing a catheter in the CSF, indeed, the intrathecal therapy allows drugs to be brought directly to the receptors of the central nervous system (CNS), reducing side effects and significantly reducing the systemic doses. An external programmable pump or surgically positioned device in the subcutaneous tissue acts as a drug reservoir and release mechanism and allows the administration of a variety of opioid and non-opioid agents.

Spasticity

Spasticity is a motor difficulty featuring tense or rigid muscles with impairment of voluntary muscle movements. It is a serious concern for many individuals affected by MS, SCI, CP, and acquired brain injury such as stroke. Increased muscle tone and spasm impair mobility and interfere with the normal activities of daily life. Spasticity can also combine with significant pain and discomfort, rupture of the skin, contracture, and sleep disorders.

The goals of the treatment are a reduction of spasticity, energy expenditure, and pain, with the aim of improving movement, walking, and autonomy in daily activities or rehabilitation therapy. Current treatments include physical therapy, oral medications, botulinum toxin, or surgery. Alternatively, or in combination with these approaches, intrathecal treatment is widely used; for this purpose, baclofen is the prescribed drug.

Contraindications

- Patients with coagulopathies

- Immunodepression. The risk of infection after implantation is a critical risk, especially in immunocompromised patients with cancer.

- Patients with a limited life expectancy (less than three months). They are more suitable for the positioning of a system (e.g., a port-a-cath device) connected to an external infuser.[12]

- Epidural metastases. Although they are not absolute contraindications, epidural metastases associated with spinal stenosis can limit the spread of drugs by inhibiting the spread to nerve roots and the spinal cord.

- Patient refusal

According to the 2017 PACC recommendations, intrathecal analgesia should be avoided in cases of widespread pain and shows poor efficacy against headaches or facial pain. Yet, ischemic heart disease or heart failure and a concomitant cerebrovascular disease should exclude the procedure.[13]

Equipment

Drugs

Three drugs: morphine, ziconotide, and baclofen, are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for intrathecal administration. However, several other opioids such as hydromorphone, fentanyl, sufentanil, and non-opioid (bupivacaine, clonidine) used alone or in combination also have indications for intrathecal administration by the Polyanalgesic Consensus Conference (PACC) recommendations for intrathecal analgesia.[14]

Morphine

Morphine-targeted opioid receptors are present in high density within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This opioid binds to receptors on primary afferent fibers (pre-synaptic) and postsynaptic neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (hyperpolarization). This binding inhibits the release of neurotransmitters such as substance P and the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), finally causing the inhibition of nociceptive transmission. Intrathecal morphine, when compared with systemic morphine, has a better analgesic effect and causes fewer side effects. Compared to lipophilic opioids (e.g., fentanyl), due to its hydrophilic nature, morphine remains localized in the intrathecal space, spreading to different levels of the spinal cord. These pharmacokinetic features lead to better pain control combined with a significant reduction in drug toxicity. Moreover, the continuous intrathecal infusion allows the drug to reach and maintain a steady-state, which results in a better therapeutic effect. In contrast, patients taking oral opioids usually experience fluctuations in the plasma level of opioids, with potential peaks in the toxic range and lowering of concentrations that lead to increased pain. Consequently, intrathecal therapy should lead to better results in terms of pain relief.[5]

Because the dose of opioids and the occurrence of adverse events are directly related, according to the paradigm 'start slow and go slow,' the doses of morphine must be kept as low as possible. The dosing of intrathecal morphine is obtainable based on the test dose (see dose titration). However, the recommended doses correspond to 1/300th of the dose of oral morphine (oral morphine equivalent dose, MED),[15] although excellent effects are achievable with much lower doses.[16] On the course of therapy, however, the maintenance of analgesia may require increased dosing as tolerance develops.

Morphine-induced side effects include respiratory depression, pruritus (due to histamine release), nausea and vomiting (due to effect on chemoreceptor trigger zone in the fourth ventricle), sedation (effect on the thalamus, limbic system). Compared to the parenteral route, the intrathecal administration of morphine can lead to an increased occurrence of urinary retention due to inhibition of the sacral parasympathetic system and, in turn, relaxation of the detrusor muscle. Although in some cases, urinary catheterization is necessary, urinary retention often resolves with the cessation of the infusion (24-hour half-life) and with the administration of naloxone.

The association of local anesthetics with opioids can potentiate the analgesic effect of morphine, also reducing its consumption. Furthermore, bupivacaine-induced side effects, such as hypotension and muscle weakness are rarely observable. Thus, it is possible to obtain good pain control through a synergistic effect of the two drugs (bupivacaine and morphine) with minimal side effects through careful patient selection, combinations of drugs for intrathecal infusion, and their dosage. Although the mechanisms of synergism remain somewhat unclear, the hypothesis is that it is due to the modulation of the electrochemical gradients of sodium and potassium and, therefore, to the subsequent release of neurotransmitters in the spinal cord with consequent improvement of cholinergic transmission in the nociceptive system. Nevertheless, the clinical effect of the association and the role of the local anesthetic infusion alone requires additional investigation. A recent randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial, indeed, demonstrated that in cancer pain, the continuous intrathecal administration of the bupivacaine alone could lead to better analgesia than the association of the local anesthetic with morphine.[17]

Ziconotide

Ziconotide is a non-opioid analgesic that selectively binds to N-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels (Cav2.2) and causes analgesia by blocking the release of pro-nociceptive neurotransmitters from nociceptive afferent nerves in the spinal cord dorsal horn. It is a peptide composed of 25 amino acids derived from the omega-conotoxin of the marine gastropod Conus magus. This medication was approved for analgesic use through intrathecal administration by the US FDA in December 2004 and, later on, the 2012 PACC guidelines recommend it as first-line intrathecal therapy for neuropathic and nociceptive pain.[18] While the most recent PACC update (2017) did not distinguish between the types of pain, it stressed that intrathecal therapy for analgesia purposes must be guaranteed not only as a rescue therapy after the failure of the high-dose systemic therapy.[19] Of note, ziconotide shows no cardiopulmonary side effects when delivered intrathecally. Again, this medication does not cause respiratory depression or physical dependence, and experience has not demonstrated symptoms of interruption of therapy. On the contrary, it is contraindicated in patients with pre-existing psychiatric disorders such as psychosis and can induce predictable increases in creatinine kinase plasma levels.[14][20]

Because ziconotide has a narrow therapeutic window, the dose titration must be accurate. The dose of ziconotide administered continuously should start with less than or equal to 1.2 mcg/day, followed by a slow upward titration with dose increases of less than or equal to 0.5 mcg/day every 4 to 7 days up to a dose maximum of 19.2 mcg/day to minimize the occurrence of adverse events.[21][22] Contrary to the intrathecal administration of morphine and other opioids, because tolerance does not develop with ziconotide, dose escalation is generally not necessary, and doses may be reducible over time.

The most frequent side effects (greater than or equal to 25%) of ziconotide are dizziness, nausea, confusion, nystagmus. Less often (less than 5%) it is possible to observe urinary retention, vision blurred, diplopia, gastrointestinal disorders (diarrhea, vomiting, constipation), pain in limb, muscle spasm, general disorders (pyrexia, asthenia, anorexia) as well as nervous system disorders (ataxia, anorexia, drowsiness, tremor, dysgeusia), and psychiatric/psychological manifestations such as anxiety, insomnia, depression, depression aggravated, and rarely psychosis with hallucination and paranoia. There have been reports of acute renal failure, atrial fibrillation, and convulsions in approximately 2%, and suicide attempts in less than 1% of patients. If side effects occur, it is advisable to reduce the dose by half.

Morphine and ziconotide are both recommended in intrathecal monotherapy against neuropathic and nociceptive pain. The choice of one rather than the other must take into consideration the characteristics of the patient as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each drug. For instance, ziconotide can be used in patients with opioid hyperalgesia or patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Baclofen

Baclofen (beta-[4-chlorophenyl]-GABA) is a muscle relaxant and antispasmodic drug, it was introduced initially as an anticonvulsant drug, in 1962. Subsequently, its use was abandoned due to adverse effects. It is an analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and acts as an agonist at the GABA-B neurons at the spinal cord level and brain. In turn, the effect is the inhibition of stretch reflexes and a decreased muscle tone.

Since when baclofen is administered orally only a limited fraction of the original dose crosses the BBB and acts on receptors in the CNS, research has demonstrated that about 25 to 30% of patients with spasticity due to SCI and MS fail to respond to therapy.[23] Intrathecal baclofen therapy s in 1tarted984, and it was shown that the application of baclofen directly in the intrathecal space has greater efficacy and fewer side effects compared to the oral route.

Intrathecal administration of baclofen usually initiates through dose titration. The patient receives a single dose (e.g., 50 mcg baclofen) and is evaluated for 5 to 10 hours to assess its efficacy. The testing dose that allows obtaining a positive response for almost 24 hours will then double. Moreover, daily dose adjustments are usually made by increments of 10 to 30% for spasticity of spinal cord origin and 5 to 15% for spasticity of cerebral origin until achieving the optimum daily dose.

The main adverse effects of baclofen include sedation, excessive muscle weakening, nausea, dizziness, mental confusion, and drowsiness, although they are less clear with intrathecal administration.[24] Furthermore, these adverse effects seem to be dose-related, and although the reported rate of treatment discontinuation due to adverse effects in up to 27% of patients, they can be prevented by starting the treatment at low doses and titrating the dose gradually upwards. In a recent retrospective analysis, conducted on intrathecally baclofen therapy for the treatment of spasticity in children, the authors proved that this therapeutic approach is also viable in children and those under 6 years of age.[25]

Device

- Programmable pump. It contains and infuses the drug. Through a dedicated software and algorithm, it stores all patient and system data

- Catheter. Positioned in the intrathecal space of the spinal cord

- External device (programmer). It allows an extra dosage of medication when needed

The pump is a mechanical pump with adjustable flow, powered by a lithium battery that has an average life of 5 to 7 years, and comes equipped with an antenna that allows communication via computer with the programmer. The pump contains the drug reservoir, which has a capacity of 20 to 40 ml. The reservoir is refillable with a thin needle introduced through the skin. According to the FDA recommendations, the reservoir should be refilled every 6 months. However, the interval varies depending on the type of disease and the drug and dose used.

The pump allows different infusion modes:

1) Continuous (fixed) infusion mode. It will enable administering the drug continuously throughout the 24 hours.

2) Flexible infusion mode. It permits the clinician to change the daily dosage of the drug; increasing or decreasing it at any time during the 24 hours, to deliver variable quantities at different times of the day, to customize the therapy based on the patient's needs.

3) Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) infusion mode. It allows, in addition to continuous administration, the administration of prefixed doses "on-demand" by the patient, such as in case of incident pain (e.g., breakthrough cancer pain).

Preparation

The test dose preceding the procedure is fundamental and allows the patient to be enrolled and to verify the dose for the titration. It can be performed continuously through a catheter connected to an external pump, or through a single bolus (0.1 mg of intrathecal morphine). Test positivity is indicated by pain reduction of at least 50% compared to the baseline. The single bolus is repeatable after 24 hours (test dose + 0.1 mg morphine) and in case of failure to respond, at a distance of 24 hours (test dose + 0.2 mg) and then 48 hours (test dose + 0.3 mg). The lack of a clinical response must lead to a re-evaluation of the patient. The effective test dose may represent the starting dose. However, to limit post-implant drug-induced side effects, the initial daily dose can be achieved by reducing the screening test dose to which the patient responded positively by 20% and thus increasing it by 20% after 3/5 days, to reach the test dose. If necessary, it is possible to increase of 10 to 20% until obtaining a correct attenuation of the pain.

Usually, the intrathecal dose of morphine can be increased gradually as in cancer pain dosages grow rapidly in the first six months and then stabilize. On the contrary, in non-cancer pain dosage increases are usually more gradual and continue over time. Of note, several studies showed that an escalation of the dose does not necessarily indicate the development of tolerance, but only that the progression of the disease, changes in the affective state, or underdose may require an increase in the dose.[4]

The preparation of the enrolled patient continues with the administration of antibiotics (e.g., cephalosporins) as prophylaxis and the preparation of surgical instruments.

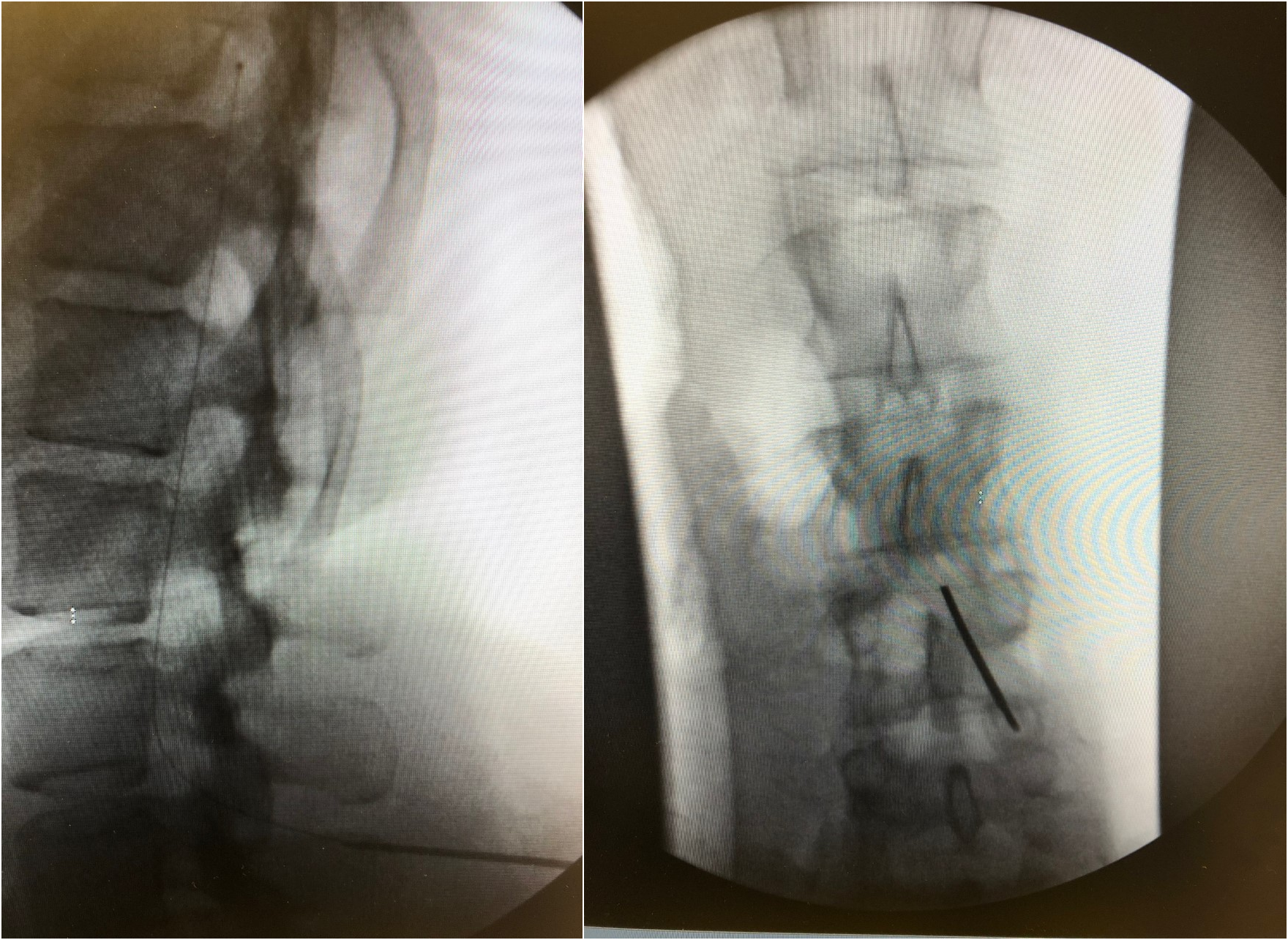

Technique or Treatment

The procedure is performed under local anesthesia with procedural sedation or general anesthesia in the operating room. General anesthesia or excessive sedation may mask potential neurological symptoms (e.g., from needle puncture) during the procedure. Aseptic precautions, including skin preparation, and sterile draping must be guaranteed. The patient is in a prone position, although some authors prefer lateral positioning. Under the guidance of X-ray fluoroscopy, an introducer needle is advanced obliquely (to avoid catheter kinking) at an angle of about 30 degrees at the point of entry of the skin (paramedian access). The choice of catheter entry site depends on the location of cancer and the related pain. Head-neck tumors may require cervical positioning; painful thoracic neoplasms (e.g., breast and lung cancers) catheters in the thoracic segment of the spinal cord, whereas lumbar catheters are generally inserted for abdominal tumors such as colorectal tumors. However, puncture at lower medullary levels is also possible and the catheter positioning can be adjusted according to need. Nevertheless, too far upwards inserted catheters can induce secondary malpositioning. For the administration of baclofen, the lumbar approach is sufficient.

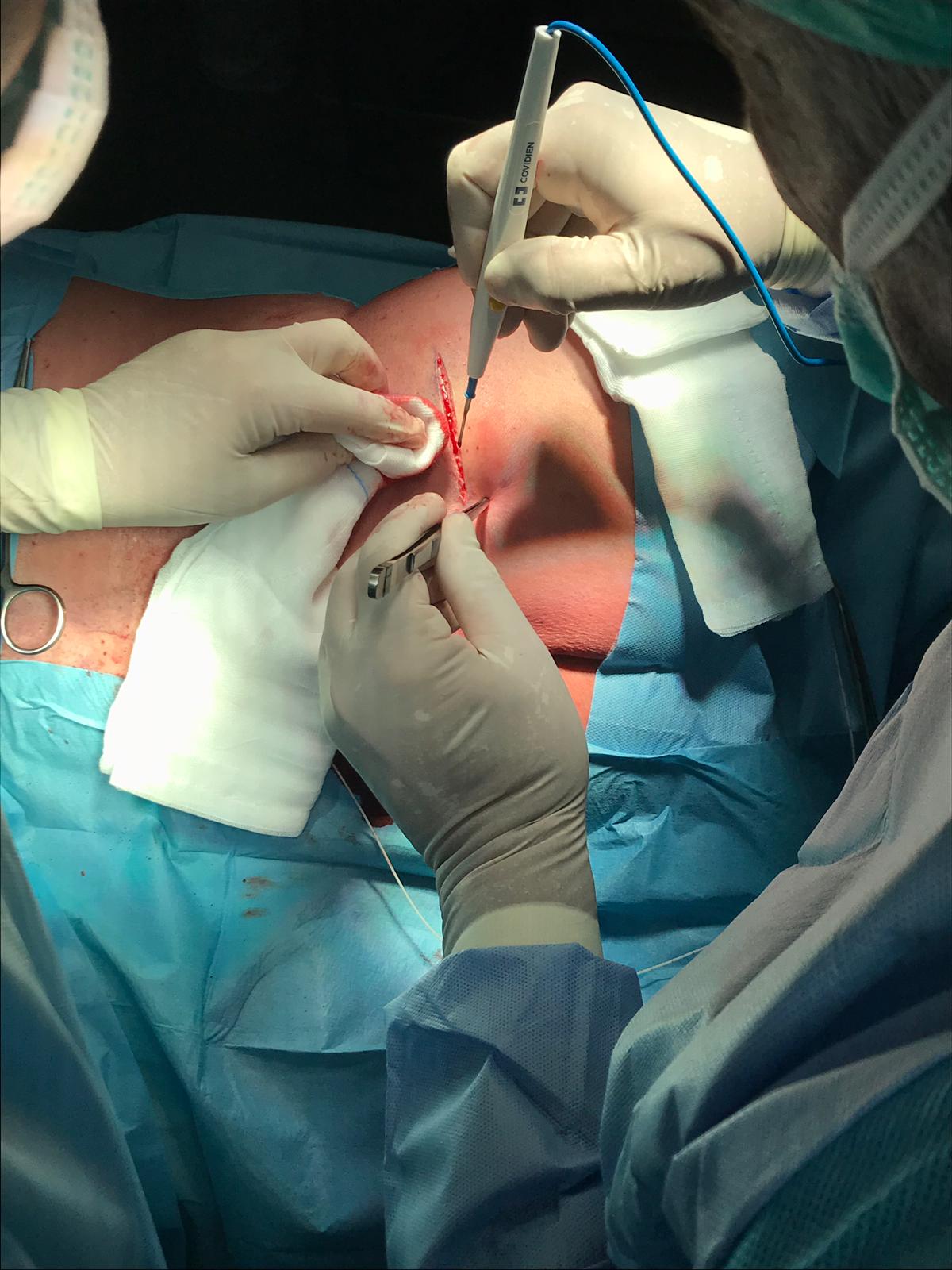

After the needle has gained access to the CSF (free flow of CSF indicates the right intrathecal positioning of the needle), the intrathecal catheter is inserted and its ascent is assessed in the subarachnoid space. After confirmation by fluoroscopy (the tip of the catheter is radiopaque) through oblique projections, the needle is generally withdrawn by about 1 cm so as to protect the catheter during subsequent maneuvers and the insertion site is enlarged by about 2 cm. After a blunt dissection, the needle is removed and the catheter is thus fixed to the paravertebral fascia through an anchoring system with non-absorbable points. The next step is the preparation of the pocket (generally in the lateral abdomen) for the positioning of the reservoir. If the patient is initially in the prone position, the decubitus position must be changed to the lateral position, perfecting the surgical field. The subcutaneous pocket is parallel to the costal arch on the anterior axillary line in the lower abdomen. If necessary, other sites can be provided (e.g., high gluteal region, Figure 1). Tunneling of the catheter in the subcutis, insertion of the reservoir in the pocket, the connection of the catheter to the reservoir (it is advisable to loop the catheter below the pump), the closure of the pocket with resorbable points and the puncture site, complete the procedure.

If the positioning of the subcutaneous pump is not foreseen, a device for the administration of drugs through a needle puncture (port-a-cath) is placed. Due to the device chamber's small size, the procedure is less complex, as well as much less expensive. This approach, however, seems to be in disuse as it exposes the patient to greater risks of infection and complicates clinical management.

Complications

Complications related to intrathecal therapy include technical or biological (infections) factors or issues related to the drugs administered.

Technical Complications

- The inaccurate subarachnoid puncture could cause radicular or medullary lesions.

- The insertion of the catheter in the subarachnoid space may involve the risk of headache (post-dural puncture headache), epidural hemorrhage and hematoma, spinal cord compression, and/or neurological conditions such as paresis.

- Occlusion (fibrin sleeve formation), lesions, dislocations, or disconnection of the catheter: catheter lesions during the procedure as well as twisting or migration of the catheter, can cause changes in the pain relief effect. Catheter kinking and dislodgements can be minimized by adopting some precautions during the procedure. These include a mid-to-upper lumbar dural entry-level, a shallow-angle paramedian oblique insertion trajectory, and accurate catheter anchoring and tunneling techniques.

- Persistent pain at the catheter or pump implantation site.

- Seroma at the pump implantation site although it can be evacuated with a simple puncture.

- Allergic reaction or rejection against implanted materials.

- Pump displacement (e.g., overturning) and/or skin erosion locally can also occur.

Catheter granuloma. A special issue among complications concerns the catheter granuloma, also referred to as catheter-associated inflammatory mass. It is a noninfectious inflammatory mass around the tip of the catheter, which is formed after a long time of positioning. The complication is generally asymptomatic, although it involves a decrease in the therapeutic effect of the device. However, when it increases its volume, a spinal cord compression that mimics a spinal epidural hematoma may occur.[26][27] Although the reduction in the dose and concentration of the drug (morphine) associated with the withdrawal of the catheter by a couple of centimeters may be effective in limiting the growth of the mass, the most serious cases indicate a neurosurgical excision of the mass. For this reason, when possible lumbar access below the medulla is preferable.

Infections

The risk of infection after implant ranges from 0.8% to 9%.[28] The risk merits consideration in immunocompromised patients with cancer. A careful aseptic technique during the whole procedure is of paramount importance. Infections include meningitis, epidural abscess, pocket infection, tunnel infection.

Drug-related Side Effects

Side effects related to the drug are mainly dose-related. In the case of morphine, these side effects include itching, nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, urinary retention, and cognitive side effects. Signs and symptoms of baclofen overdose include drowsiness, lightheadedness, dizziness, drowsiness, respiratory depression, convulsions, rostral progression of hypotonia, loss of consciousness, which progresses to a coma. Abrupt withdrawal of baclofen can be life-threatening. The symptoms are high fever, altered mental status, the exaggerated rebound effect of spasticity, and muscle stiffness. A not-treated suspension can lead to rhabdomyolysis, multiple organ failure, and death.

Clinical Evaluation

Patients must be carefully monitored at each visit and checked for new neurological signs or symptoms, including progressive change of type, quantity, or intensity of pain or spasticity, especially despite the increase in dose, sensory changes such as numbness, tingling, and burning, hyperesthesia and/or hyperalgesia. Other local (catheter insertion site, tunnel, pocket) and general symptoms (e.g., fever) require investigation.[29]

Symptoms that require immediate diagnosis and treatment include constipation, urinary retention, myelopathy, cauda equina syndrome symptoms (weakness, tingling, or numbness in the legs, saddle anesthesia, lower back and/or pelvic pain, bladder or bowel incontinence), gait disturbances, or difficulty walking, paraparesis or paralysis, respiratory depression, hypotonia, confusion, and excessive sedation.

If an inflammatory mass is suspected (catheter granuloma), the recommended evaluation should include an analysis of the patient's medical history combined with a neurological evaluation and radiological diagnostic procedures.[29]

Clinical Significance

Several randomized controlled trials, as well as prospective and retrospective studies, have shown that intrathecal therapy is safe and effective for controlling cancer-related and non-cancer pain as well as severe spasticity. However, intrathecal treatment is not without risk. For this reason, it must be managed in specific centers, by a multi-disciplinary team that can adequately select the patient by evaluating the risks and benefits of an invasive therapy, as well as the complications and costs, to obtain the best results. A team that involves the collaboration of an oncologist, radiologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, palliative care and pain medicine, and nurses would be desirable. The selection of the patient, the timing of implantation of the catheter, the management of the patient to quickly identify any complications, and side effects are crucial for the success of the therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The continuous administration of drugs by the intrathecal route is a viable and relatively safe option for the treatment of chronic painful conditions associated or not with oncological pathology, and for the treatment of severe spasticity, also in children. Further research and expert opinions are needed to improve our current knowledge about the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model of intrathecal drug administration and to evaluate the use and safety of other drugs not currently indicated for this purpose. Results from these investigations will undoubtedly lead to a widening of indications. Furthermore, in patients with cancer, the life expectancy of fewer than three months sets a limit to the execution of the procedure. This indication, probably dictated by the last costs of the procedure, should be revised since the major target of palliative therapy is the improvement of the HR-QOL regardless of the life expectancy.

Finally, the formation of a dedicated interprofessional healthcare team is mandatory for the success of this therapy. The possibility of having qualified personnel is fundamental to the success of the procedure. This team includes specialty-trained pain management nursing staff or a palliative nurse, for administration and monitoring and continuously evaluate the progress of the therapy, performing the necessary dosage changes, and evaluating potential side effects. This approach requires knowledge of advanced devices and appropriate algorithms. The pharmacist will prepare the doses and should verify dosing ordered and check for potential interactions, reporting their findings to the treating clinicians. All this should happen under the aegis of a clinician specializing in pain management, so that the entire interprofessional team is well-versed in the parameters and monitoring of this therapy, and can direct patient outcomes optimally. [Level V]