Continuing Education Activity

Hollenhorst plaques, named after the American ophthalmologist Robert Hollenhorst, are microscopic cholesterol emboli that can be found in the small blood vessels of the retina. These tiny, yellowish fragments typically originate from atherosclerotic plaques in larger arteries, breaking off and traveling through the bloodstream until lodging in the retinal vessels. Hollenhorst plaques are often associated with systemic vascular diseases, particularly atherosclerosis, and their presence in the retinal circulation can have significant implications for the patient's overall health. Identifying these plaques during a retinal examination is crucial, as it may serve as a clinical indicator of underlying cardiovascular conditions, prompting further investigation and intervention to manage the patient's vascular health. Understanding the significance of Hollenhorst plaques is essential for healthcare professionals in ophthalmology, cardiology, and general medicine, as it underscores the interconnectedness of ocular and systemic health.

This activity provides a comprehensive exploration of Hollenhorst plaques, spanning presentation recognition, evaluation, and management. The paramount role of Hollenhorst plaques as the primary cause of ocular ischemic syndrome post-retinal artery occlusion will be reviewed. Participants gain insights into improving patient outcomes and aligning management strategies with evolving standards in the field. The critical importance of an interprofessional team approach in delivering optimal care to affected patients will also be addressed.

Objectives:

Assess patients for the presence of Hollenhorst plaques, considering risk factors such as age, hypertension, and atherosclerosis to enable early detection and intervention.

Differentiate between Hollenhorst plaques and other retinal pathologies during ocular examinations, utilizing diagnostic skills to accurately identify these cholesterol emboli.

Implement evidence-based strategies for managing patients with Hollenhorst plaques, including initiating appropriate medical interventions and referrals to specialists in cardiology and vascular medicine for comprehensive care.

Collaborate with an interprofessional team to ensure a multidisciplinary approach to managing patients with Hollenhorst plaques, addressing both ocular and systemic aspects of their health.

Introduction

Stroke is the third most common cause of death in the United States. Eighty percent of all strokes are due to vessel occlusion secondary to atherothrombosis or embolus. Hollenhorst plaque (HP) was discovered in 1961 by Dr. Robert Hollenhorst. He defined them as tiny emboli caused by cholesterol plaques and found in the retina's small blood vessels. The appearance of these emboli indicates that they are yellow, refractile, and typically located at an arterial bifurcation.[1][2] Hollenhorst plague is the most common cause accounting for the ocular ischemic syndrome (OIS) following retinal artery occlusion (RAO).[3]

History

In 1927, T. Harrison Butler first mentioned a bright retinal embolus involving the inferior temporal arteriole. Hollenhorst, Witmer, and Schmid described this lesion in 1958.[4] Hollenhorst postulated that the cholesterol ester is the fundamental component of the lesion, and he proposed a temporal relationship, foreseeing the risk of subsequent cerebral ischemic events on the side ipsilateral to symptomatic carotid disease. He also confirmed that this plague was mobile upon manual ocular pressure.[4] In 1961, Hollenhorst detailed the characteristics of these vivid, orange-appearing plaques in his paper titled "Significance of Bright Plaques in Retinal Arterioles." These plaques were identified in 11% of cohorts with carotid disease and 4% with vertebrobasilar diseases. The plaques rarely obstruct arterioles, instead frequently migrating to distal vessels and ultimately dissipating through fragmentation.[4] Hollenhorst and Jack Whisnant reproduced retinal plaques mirroring those observed in humans through the injection of cholesterol crystals and human atheromatous material into the carotids of experimental animals. This was validated in 1963 from an autopsy of a patient who had similar appearing retinal plaques and who had died following carotid endarterectomy (CEA).[4]

Etiology

HPs tend to originate from carotid arteries or the aorta. This finding is consistent with carotid disease originating from atherosclerotic lesions. Upon discovering an HP, eye care professionals initially assumed that it originated from the stenosed, ipsilateral internal carotid artery (ICA). The direct anatomical route between the ICA and the central retinal artery (CRA) supports this assumption. The ophthalmic artery is the first branch of the ICA, which then leads into the CRA.[5][6]

Epidemiology

The Blue Mountains Eye study stated that the prevalence of retinal emboli is 1.4% in the general population older than 49 years.[7] The prevalence increases with age. Retinal emboli are significantly more prevalent in men than in women. HPs make up 80% of retinal emboli. An estimated 10% of carotid emboli reach the retinal arteries.[8]

In the Beaver Dam Eye Study, comprising almost 5000 patients, the prevalence of HPs was 1.3%, and the 5-year incidence was 0.9%.[9] In a study of 130 consecutive patients with a diagnosis of HP alongside central or branch RAO, the mean age of the patients was 68 ± 16 years, and the incidence of symptomatic patients was 61%.[10]

The incidence of asymptomatic retinal emboli is 1.4%. Cholesterol emboli are more prevalent in men than women (2.2% vs 0.8%).[11][12] Eighty percent of all retinal emboli are of the cholesterol type.[4][11] Significant links with hypertension (odds ratio [OR], -2.2), vascular disease (OR, -2.4), past vascular surgery (OR, -3.5), and current smoking history (OR, -2.2) or any smoking history (OR, -2.6) have been observed.[11]

Pathophysiology

Ulcerated plaques just distal to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery into its external and internal branches may be a source of retinal emboli that can be asymptomatic or produce transient monocular blindness.[13][14] Cholesterol plaques are seen in the retina owing to their relatively small size and decreased velocity while traveling through the internal carotid system.

History and Physical

HP is a marker of past embolic events but is a poor predictor of future events. These plaques may or may not cause an RAO. The discovery of asymptomatic emboli has a greater concern for a patient’s systemic health than visual health. Most HPs are discovered incidentally during funduscopy. They often dislodge and are not noted on subsequent fundus examinations.

An HP is a clinical sign, commonly a contributing factor in diagnosing RAO. The plaque must completely obstruct the vessel for an HP to cause an RAO. RAOs can occur in the central retinal artery (CRAO) or one of its branches (BRAO). HP is a possible cause of a CRAO/BRAO and should not be considered synonymous.

As noted in the differential diagnosis, other types of emboli can occlude the relevant vessels. There are also nonembolic causes of RAO, including nocturnal arterial hypotension and transient vasospasm. HP, like other types of retinal emboli, may not stay in 1 place. The plaque may dislodge and move to a smaller diameter vessel before it gets lodged again, or the plaque may dissolve completely. The presence of an HP is a confirming diagnosis; however, the absence of a plaque does not rule out the possibility of embolic occlusion.

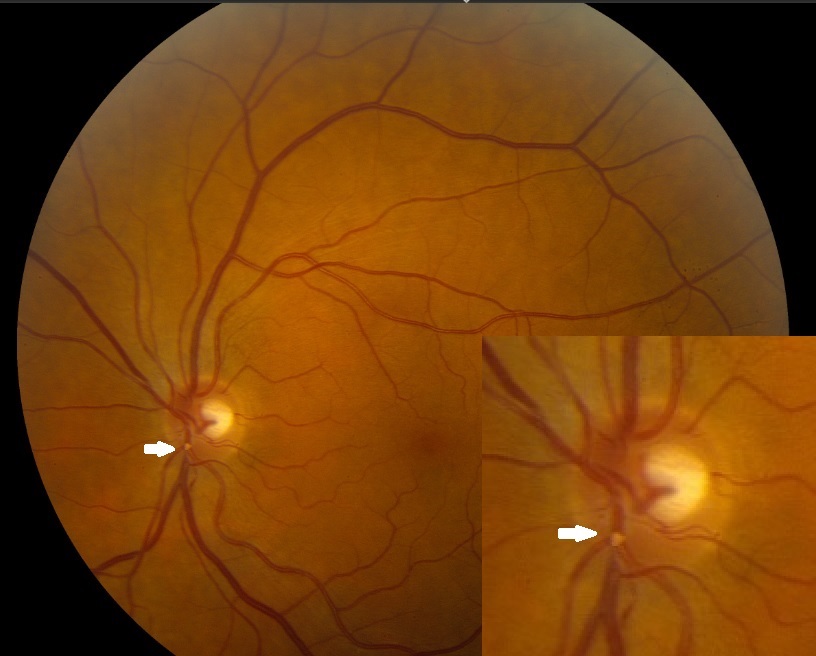

If an RAO occurs, the most common symptom is sudden, painless vision loss. The fundus will display typical ischemic signs, such as retinal whitening around the occluded vessel (see Images. Hollenhorst Plaques). The macular area will remain “cherry-red” due to its secondary outer retinal blood supply. If the plaque only partially occludes the vessel, blood can still flow through the lumen, and no damage occurs. A single eye can undergo more than 1 transient RAO.

Evaluation

Diagnostic tools which may be employed in the evaluation of HPs include the following:

Auscultation of the ipsilateral carotid for the presence of a bruit.

Blood pressure measurement to rule out hypertension or hypotension.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) for atrial fibrillation (AF).

Carotid duplex study- A significant stenosis is characterized by a diameter reduction of 80% to 99%, a peak systolic velocity of >125cm/sec, and an end-diastolic velocity of>140cm/sec alongside extensive spectral broadening. Carotid bifurcation stenosis was <30% in 68% of the patients, between 30% and 60% in 22% of the patients, and >60% in only 8% of the patients.[10] Significant carotid internal artery stenosis was detected in 7% to 20% of patients with asymptomatic retinal emboli and 20% to 25% of patients with BRAOs.[15]

Echocardiography (ECHO) study for determining the cardio-embolic source.

CT or MRI 4-vessel carotid angiography to evaluate for stenosis, dissection, and/or dysplasia. CT angiography has a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 93%.[16]

Blood test for ruling out any hypercoagulopathy.

Fluorescein angiography shows delayed or absent fill in the retinal artery (most specific sign), prolonged arteriovenous transit time (most sensitive sign), and capillary nonperfusion (loss of endothelial cells, pericytes, and lumen obliteration). Staining of retinal vessels (endothelial cell damage due to chronic ischemia), macular edema, and hyperfluorescence within the optic disk in OIS are also observed, caused by leakage from the disk and capillaries.[3][17] Indocyanine green angiography shows prolonged arm-to-choroid and intrachoroidal circulation times and slow filling of the watershed zones.[3]

Visual-evoked potentials (VEP), electroretinography (ERG), and ophthalmo-tonometry are seldom used.[3] Electroretinography shows reduced amplitudes of both the a- and b-waves.[18]

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows thick, hyperreflective inner retinal layers with blocked outer retina reflectivity. Eventually, the retina is thinned out and appears atrophic. This also demonstrates a reduction in the foveal avascular zone and improved vessel density in all retinal layers after carotid artery stenting for OIS.[19]

B-scan ultrasonography or orbital computed tomography (CT) scan to rule out compressive lesions.

Treatment / Management

Immediate ocular massage may help dislodge the emboli.[17] Irreversible retinal damage occurs within 240 minutes of central RAO.

Surgical embolus removal was first attempted in 1990 by Peyman and Gremillion. This was achieved in 87.5% with reperfusion and improved visual acuity in 4 of 6 patients in 1 study.[17]

The treatment decision for carotid stenosis is primarily based on the degree of stenosis and associated symptomatology.

For patients with <50% stenosis - antiplatelet therapy is advocated in the form of:

- Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor- Aspirin

- Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitor- Clopidogrel and

- ADP reuptake inhibitor- Dipyridamole

This minimizes the risk of a 5-year stroke rate by almost 50%. Subgroup analysis in the Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels trial revealed that atorvastatin reduced the risk of both cerebrovascular and cardiovascular adverse events.[20]

For patients with >70% stenosis - are considered for surgical interventions in the form of either CEA or carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS). Both are safe and effective, with increased odds of myocardial infarction following CEA and an increased risk of stroke following CAS. They also have a comparable risk for fatal or disabling stroke.[21] Evidence is poor for purely ocular transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) showed that surgical intervention was markedly effective with cohorts with 70% to 99% stenosis.[22] This significantly reduced the 2-year risk of ipsilateral stroke rate compared to medical management alone (9% vs 26%) among symptomatic cohorts presenting with transient monocular visual loss, transient ischemic attack, or nondisabling strokes. Comparable findings were observed among symptomatic patients within the European Carotid Surgical Trial.[23] A meta-analysis comprising 5223 patients with asymptomatic moderate to severe stenosis and low perioperative risks favored CEA (relative risk, 0.69). CAS is also comparable to endarterectomy in terms of risk of procedural stroke (2.9 vs 1.7%) and survival (87.1% vs 89.4%). The 5-year stroke-free survival was similar (93.1% vs 94.7%).[24]

For patients with 50% to 69% stenosis - there was a considerable drop in the benefits following surgery.

The Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study and Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial showed a risk reduction of 53% and 46% among cohorts with 60% stenosis with CEA.[25] Guidelines recommend CEA when the risk of perioperative stroke, myocardial infarction, or mortality is considerably low.

No ocular treatment is necessary unless an HP completely obstructs a vessel, causing an RAO. All patients with retinal emboli should be referred to the patient’s primary care provider for a bilateral carotid duplex study. The management considers the following:

- Patient education on HA as primarily an underlying etiology

- Lifestyle modifications and combating risk variables (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sedentary lifestyles, obesity, cigarette smoking) and

- Aspirin for arteriosclerosis

Differential Diagnosis

Types of Retinal Emboli:

- Calcific emboli- appear whitish, involve the central retinal artery, do not dissolve, and originate from cardiac valves or aorta calcification.

- Fibrinoplatelet emboli- appear dull white within the retinal arteriole and arise from carotid thrombus.

- Talc emboli- observed in patients with an intravenous drug and/or cocaine addiction, are relatively small and appear parafoveally.[26]

- Metastatic tumor cells

- Septic emboli- following bacterial endocarditis

- Fat emboli- occur following long bone fractures and have concomitant scattered retinal microinfarcts and hemorrhages.[27]

- Amniotic fluid emboli [28]

- Air emboli [17][29]

Prognosis

The atheromatous disease of the ICA can be associated with HPs and is usually an indicator of potential stroke. Carotid stenosis increases stroke risk by 1.18 times for every 10% increase in stenosis. This risk of stroke rises <1% per year for a vessel that is <80% stenosed. On the contrary, a vessel >90% stenosed raises the stroke risk by 4.8% per year.

Almost 75% of HPs are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic HP, however, is a poor predictor of future embolic events.[12] However, 25% of these cohorts have carotid stenosis of >40%.[4] Symptomatic patients were more likely to harbor carotid stenosis >69% when compared with asymptomatic patients (25% vs 9.2%).[12]

Patients with retinal cholesterol plaques had a higher incidence of stroke compared to their healthy counterparts (8.5% vs 0.8%).[12] Cholesterol emboli have a 15% risk of mortality at 1 year, 29% at 3 years, and 54% at 7 years.[12] Hollenhorst observed that survival reduced by almost 15% and 40% at 1 and 8 years, respectively, in patients with retinal cholesterol embolism.[4] These patients have increased odds of stroke-related deaths (hazard ratio, 2.61).[9] The cumulative mortality was 56% with retinal emboli and 30% without retinal emboli.[4] The risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction or vascular death was 7.7% (4.9% among controls).[30]

Asymptomatic retinal cholesterol embolism is a risk variable for cerebral infarction.[30] In a meta-analysis of 1343 patients with asymptomatic cholesterol emboli, 17.8% had a history of either cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or TIAs at presentation. Twelve percent of these patients evolved to stroke, TIAs, or death during their follow-up.[31] The evidence suggests that these patients warrant referral for medical optimization of pertinent cardiovascular risk factors.

Currently, no recommendation exists to support CEA in patients with HPs or retinal emboli alone.[31] In a study with 159 patients with CRAO, 284 with BRAO, and 85 with HP, mortality and cerebrovascular events were statistically significantly higher in only the CRAO and BRAO groups.

Complications

Complications of HPs include the following:

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO)

- Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO)

- Ischemic strokes [32]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education play pivotal roles in addressing the implications of HPs and promoting vascular health. Clinicians engaging in deterrence strategies focus on identifying and managing risk factors associated with plaque formation, such as hypertension and atherosclerosis. By emphasizing lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining a heart-healthy diet, regular exercise, and smoking cessation, healthcare providers contribute to preventing HPs and related vascular issues.

Concurrently, patient education is a cornerstone in empowering individuals with knowledge about the significance of these cholesterol emboli, potential risks, and available preventive measures. Educating patients on recognizing early symptoms, the importance of regular eye examinations, and adherence to prescribed medications fosters proactive involvement in their own healthcare, facilitating early detection and intervention to mitigate the impact of HPs on both ocular and systemic health. Together, deterrence and patient education create a foundation for informed decision-making and collaborative efforts in preserving overall vascular well-being.

Pearls and Other Issues

HPs are yellow and refractile, typically located at the carotid artery bifurcation. They tend to originate from carotid arteries or the aorta secondary to atherosclerotic lesions. The salient features include the following:

- HPs are considered to be the most common form of emboli.

- HPs are a common finding in the aging population.

- Approximately 75% of HPs seen in ophthalmic practice are asymptomatic.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Even though there are several other causes of HPs, the most problematic diagnosis is atherosclerosis of the ICA. Often, the presence of an HP indicates an impending stroke, especially in older individuals. Once an HP has been diagnosed, the management generally involves a neurologist, ophthalmologist, cardiologist, vascular surgeon, interventional radiologist, nurse, and pharmacist, functioning as a cohesive interprofessional team.

Healthcare professionals managing patients with HPs need refined clinical skills for accurate diagnosis, including proficiency in ophthalmic examinations and the interpretation of retinal findings. Advanced practitioners, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, may play a crucial role in gathering comprehensive patient histories and conducting initial assessments.

The patient should undergo a duplex ultrasound of the neck to determine the presence of atherosclerotic disease at the carotid bifurcation. If the lesion is ulcerated and has >70% stenosis, the patient should be referred to a vascular surgeon or an interventional radiologist for either CEA or CAS. The patient should be encouraged to lower his blood pressure and cholesterol, discontinue smoking, and take aspirin while awaiting surgery. The nurse should educate the patient on possible stroke symptoms and when to return to the emergency room. When patients with carotid artery atherosclerosis are managed with elective surgery or stenting, the morbidity and mortality rates are <3%.[6][10] This type of interprofessional collaboration will foster improved results.

For patients with symptomatic HP, risk factors and cost-utility analyses are justified.[9] Despite asymptomatic emboli, a medical referral is beneficial. HP with concurrent venous stasis retinopathy confers more conclusive evidence for the same.[33] Positive predictive values of carotid stenosis for the ocular signs/symptoms of amaurosis fugax (18.2%), HPs (20.0%), and venous stasis retinopathy (20.0%) have been observed. Patients with carotid duplex showing ulcerated atheromatous plagues causing >70% stenosis should be referred for either CEA or CAS.

Developing a cohesive strategy for managing patients with HPs involves aligning diagnostic and treatment approaches among the healthcare team. Physicians, in collaboration with pharmacists, can strategize effective medication regimens for managing underlying vascular conditions contributing to plaque formation. Advanced care practitioners may contribute to the development and implementation of patient care plans, ensuring continuity and consistency.

Effective communication among healthcare professionals is essential for delivering patient-centered care. Team members must share relevant information, discuss treatment plans, and collaborate on interventions. Clear and open communication ensures that all team members are aligned in their understanding of the patient's condition and goals of care. A coordinated approach ensures that patients with HPs receive holistic and timely care across different healthcare settings.

A multidisciplinary approach involving physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals is crucial for enhancing patient-centered care, improving outcomes, ensuring patient safety, and optimizing team performance in managing patients with HPs. Effective communication and coordinated interprofessional team efforts contribute to a comprehensive, patient-focused care strategy.