Continuing Education Activity

In the United States, hip dislocations are responsible for significant morbidity and potentially mortality with deleterious consequences to the surrounding anatomy, neighboring joints, and an individual's functional ability. In the evaluation of posterior hip (femur) dislocation, whether the patient has a native hip versus a prosthetic hip joint is the first question any examiner should answer as the clinical approach varies significantly. Additionally, it is paramount to evaluate for associated injuries such as fractures, as this will also drastically alter management. Due to the traumatic nature and force required to dislocate a native hip joint, it is not surprising that 95% of patients who present with a hip dislocation after a motor vehicle collision had an associated injury requiring inpatient management. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of posterior hip dislocations and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for those with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the mechanisms of injury and pathophysiology of posterior hip dislocation injuries.

- Summarize the diagnostic procedure for evaluating posterior hip dislocations, including any imaging needed.

- Review the treatment and rehabilitative options for posterior hip dislocation injuries.

- Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by posterior hip dislocation.

Introduction

In the United States, hip dislocations are responsible for significant morbidity and potentially mortality with deleterious consequences to the surrounding anatomy, neighboring joints, and an individual's functional ability.[1]

In the evaluation of posterior hip (femur) dislocation, the first question an examiner should answer is whether the patient has a native hip or a prosthetic hip joint, as the clinical approach varies significantly. Additionally, it is paramount to evaluate for associated injuries such as fractures, as this will also drastically alter management.

The native hip joint is inherently stable and requires a significant amount of force to cause dislocation; as such, hip dislocation in native joints are often secondary to traumatic events such as motor vehicle accidents. Due to the traumatic nature and force required to dislocate a native hip joint, it is not surprising that 95% of patients who present with a hip dislocation after a motor vehicle collision had an associated injury requiring inpatient management.[2][1] Thus, with native hip dislocation, a detailed neurologic and musculoskeletal examination with additional x-ray or CT scans for assessment is mandatory. Conversely, prosthetic or non-native hip dislocations are a relatively common occurrence to emergency departments nationwide as the inherent stability of the joint is less than that of a native joint. Prosthetic joint dislocations are most often associated with minor mechanisms and require a more reserved approach.[3][4][5]

Etiology

Hip dislocations may occur in either an anterior or posterior fashion that is dependent upon the inciting mechanism. In posterior dislocations, the femoral head is displaced posteriorly in relation to the acetabulum. Hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation will produce posterior dislocations, whereas hyper-abduction with the extension will produce an anterior dislocation, with the large majority of atypical and axial-loading injury patterns producing posterior dislocation. [5]

Epidemiology

Age, race, and gender are important risk factors for these types of injuries with the incidence being two times greater in women than in men. Posterior hip dislocations (90%) are much more common than anterior hip dislocations; additionally, there is significant morbidity and mortality associated with posterior hip dislocations if there are any associated fractures. In addition to severe pain, other associated injuries include acetabular fracture, hip/femur fracture, osteonecrosis, sciatic nerve damage, recurrent dislocations, bone bruise (33%), ipsilateral knee meniscal tears (30%), knee effusion (37%) and labral tear (30% rate) [4]. In addition, thoracic aortic injury has been reported to be associated with posterior hip dislocation in 8% of cases due to abrupt deceleration injuries [6].

Following dislocation, physicians will typically attempt to reduce the dislocation with sedation via a closed procedure/technique. Emergent closed reductions are warranted, especially in the setting of native hip joints to ameliorate the risk of osteonecrosis. If all attempts at a closed reduction fail, an orthopedic surgeon will perform the reduction with an open, surgical procedure. After the reduction, whether it is open or closed, there are strict precautions patients must follow to prevent re-dislocation and further injury. If a patient suffers recurrent dislocations, bracing or even further corrective surgery is often indicated. [4]

Pathophysiology

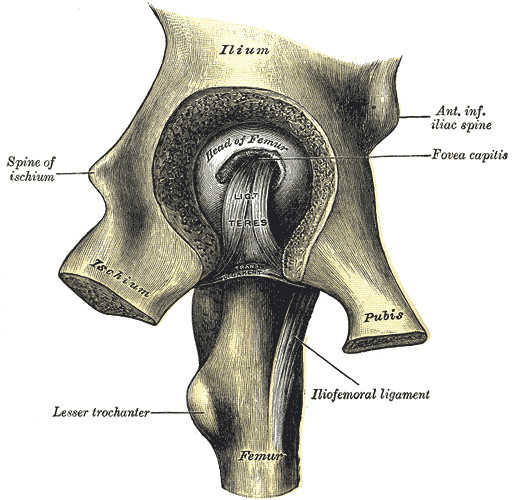

A hip dislocation occurs when the internal forces of the hip (labrum, capsule, ligamentum teres, muscles, bones, and mechanical anatomy) are overpowered by the transmission of a large amount of energy through the joint.

In the setting of a hip prosthesis, the normal hip anatomy and support structures may be violated or replaced (external rotators, joint capsule, acetabular surface and femoral head) during surgery. This violation can result in a decrease in the amount of inherent/anatomic force that helps maintain the femoral head within the acetabulum, therefore reducing the amount of energy necessary for a dislocation to occur. Important risk factors that mechanically predispose individuals with prosthetic hip implants to dislocate include:

- Surgical approach utilized (for example, anterior versus posterior)

- Type of prosthesis (hemi versus total arthroplasty)

- Prior hip surgery

- Female gender

- Malposition of the prosthesis during surgery

- Drug/alcohol abuse, and

- Neuromuscular disease such as Parkinson.

Typical mechanisms of dislocation for the non-native hip include falls, bending down to tie one's shoes, sitting on a low/short chair then attempting to stand, or crossing one's legs when sitting, standing, or lying down.

As previously mentioned, native hip dislocations are secondary to traumatic events; a common mechanism occurs during motor vehicle collisions when a person's flexed knee strikes the dashboard of the car, creating an axial load transferring a large amount of force through the hip joint.[7][8]

History and Physical

Posterior hip dislocation is rarely, if ever, an occult injury due to the amount of pain elicited as well as an inability to ambulate or bear weight on the affected extremity afterward. The patient's history will usually involve a description/experience in which there was a significant "clunk" or "popping" followed immediately by pain. A physical deformity with ipsilateral shortening/hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation will be visible. It is also important to examine the pelvis and ipsilateral knee. If necessary, especially in the setting of native hip dislocation, ATLS principles of practice should be applied. A thorough neurovascular examination should be performed and documented at presentation, before and after reduction and serial examination thereafter.

The following can be suggestive signs of vascular or sciatic nerve injury:

- Local hematoma.

- Painful buttock, posterior thigh, and leg.

- Altered sensation in posterior leg and foot.

- Weakness or total loss of dorsiflexion (peroneal branch) or plantar flexion (tibial branch).

- Diminished or absent deep tendon reflexes at the ankle.

Evaluation

After a thorough history and physical examination, imaging of the affected joint is necessary.

Standard anteroposterior pelvic radiographs: Several contour lines that should be continuous and smooth helps systematic interpretation. Iliopectineal and ilioischial lines represent anterior and posterior columns of the acetabulum respectively. Careful assessment of the posterior wall of the acetabulum as posterior wall fracture is the most commonly encountered acetabular fracture pattern in hip dislocation. Shenton's line irregularity occurs in hip dislocation or in the neck of femur fractures without dislocation. Assess if the femoral head fracture is present whether it is above or below fovea capitis. The femoral head appears smaller than the contralateral side.

Crosstable lateral view: Identify the direction of dislocation.

Additional Judet views (45 degree internal and external oblique views), inlet and outlet views: This can be helpful in identifying acetabular fractures.

Computed tomography CT: Post reduction CT is mandatory for all traumatic hip dislocation. It identifies any associated femoral head or acetabular fracture and delineates its extent. Also, it is helpful in finding out any incarcerated bony fragments or loose bodies.[9]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging MRI: It is controversial and should not be routinely employed [4]. However, It can be helpful in assessing soft tissue injuries e.g labrum, cartilage. Also, MRI is superior to CT in the pediatric population with an immature skeleton.

Treatment / Management

The management of posterior hip dislocations can be divided into into-operative and non-operative techniques. Both types of management are aimed at a reduction as soon as possible. Numerous studies have cited that time to reduction is crucial because the longer the hip is dislocated, the higher the risk of complications, specifically avascular necrosis in the native hip. Most authors recommend a reduction time of fewer than 6 hours, while there is some evidence that fewer than 12 hours may be a critical time; regardless, the rate of secondary complications increases dramatically with increased time-to-reduction. [10]

Non-Operative Management/Closed Reduction

The first closed reduction maneuver for hip dislocation was described by Bigelow in 1870. This has been followed throughout the literature by several other techniques, each has its own merits and limitations [11]. Allis has described the most commonly used technique for the reduction of posterior hip dislocation. The patient lies supine and the operator holds the knee flexed at 90 degrees. With an assistant stabilizing the pelvis, the operator applies traction in line with the femur while flexing the hip up to 90 degrees by holding the patient’s knee. Originally Allis described no rotation to be performed. As the hip reduces, the operator gently extends the hip and externally rotates the leg to allow the femoral head to enter the acetabulum. The following is a list of other reduction maneuvers [11] that can be utilized to reduce hip dislocation.

In all techniques, unless stated otherwise, the patient is placed supine on a stretcher, bed or operating table. The operator stands on the side of the affected hip.

Bigelow Maneuver

An assistant stabilizes the pelvis. The operator holds the ankle of the affected leg with one hand and the forearm is under the ipsilateral knee. The hip is flexed to 90 degrees with the ipsilateral lower extremity adducted and internally rotated. Inline femur traction is applied along with abduction, external rotation, and extension of the affected hip.

Lefkowitz Maneuver

The operator puts his knee under the patient’s ipsilateral knee in the popliteal fossa and puts his own foot on the Stretcher. With one hand on the patient’s lower anterior thigh and the other hand on the lower leg flexing the patient's knee until the hip is reduced [12].

Captain Morgan Maneuver

The patient is supine on a backboard on a stretcher with the pelvis strapped to the board. The operator flexes the patient’s affected leg over his own thigh, close to the popliteal fossa. Then, the operator plantar flexes his foot meanwhile applying upward traction with one hand under the ipsilateral knee and the other hand holding the ipsilateral ankle controlling rotational, abduction, and adduction movements until the hip is reduced [13].

East Baltimore Lift ManeuverThe operator stands on the side of the affected hip, with the assistant on the opposite side with their knees flexed. They put their arms underneath the knee of the patient’s affected hip applying upward force in line with the femur by extending their knees. Meanwhile, they support their hands on each others’ shoulders with their free hands stabilizing the pelvis. A second assistant at the foot of the stretcher applies a downward leveraging force on the ankle and controls rotational, abduction, and adduction movement to reduce the hip [14].

Howard Maneuver

The operator and assistant stand on the side of the affected hip. The assistant applies a lateral traction force on the thigh of the affected side . The operator holds the lower leg by the knee flexing the hip to 90 degrees, then applies traction in line of the femur and uses internal and external rotation until reduction is achieved [15].

Lateral Traction Method

The operator applies longitudinal force in line with the femur, while an assistant uses a sheet wrapped around the inner thigh of the patient to apply lateral traction until reduction is achieved. rotational movement is used as necessary [16].

Piggyback Method

The patient is brought to the end of the stretcher. The operator flexes the patient's hip and places the patient's knee over his own shoulder using it as a fulcrum and applies a downward force on the tibia until reduction is achieved [17].

Tulsa technique/Rochester technique/Whistler Technique

The patient lies supine with both legs flexed. The operator holds the contralateral knee with one hand so that the ipsilateral knee is flexed over his forearm. With the other hand on the ipsilateral ankle applying downward traction and rotational movement to reduce the hip [18][19][20]

Flexion Adduction Method

Under general anesthesia, with the operator standing on the unaffected side and lifting the affected leg into flexion and maximum adduction whilst maintaining inline traction with the femur. An assistant stabilizes the pelvis and manually pushes the femoral head into acetabulum [21].

Foot-fulcrum Maneuver

The operator sits on the bed at the patient’s feet and maximally flexes the affected hip displacing the femoral head more posteriorly in order not to get stuck at the acetabulum rim. The operator puts one foot against the anterior aspect of the ipsilateral ankle and the other foot on the posterolateral aspect of the affected hip. Next, the operator holds the ipsilateral flexed knee and leans backward, using his feet as the fulcrum and applying inline femur traction. If necessary, leaning from side to side can control rotational movement [22].

The Waddell Technique

An assistant stabilizes the patient’s pelvis on the bed. The operator hovers over the patient and puts his forearm behind the patient's knee so that the lower leg hangs freely. The operator's forearm rests with the elbow on his own knee and the hand on the other knee. The operator holds the patients’ knee close to the chest with the affected hip is flexed between 60 to 90 degrees and the knee is flexed to 90 degrees. The surgeon then gently leans backward with his feet as a pivot and applying inline femur traction. Adduction and rotational movement is applied as necessary.

Skoff Maneuver

The patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus with the affected leg upwards. The assistant applies lateral traction on the femur whilst the lower extremity positioned in 90 degrees of hip flexion, 45-degree internal rotation, and 45-degree adduction and 90 degrees of knee flexion. Meanwhile, the operator feels the deformity in the gluteal and pushes the femoral head until reduction into the acetabulum [23].

Traction Counter Maneuver

The positioning of the patient and the affected extremity is similar to the Skoff method but the assistant stands within a looped strap placed around the patient’s groin and over the iliac crest leaning backward providing lateral traction. The operator stands in a separate looped strap and places it around the patient’s knee then leans back providing lateral traction in line of the femur, while manipulating the affected leg with his hands. The assistant feels the deformity in the gluteal region, and pushes the femoral head reducing it in the acetabulum [24].

Stimson Gravity Maneuver

The patient is positioned prone with the lower limbs flexed 90 degrees at the hips and knees over the edge of a stretcher. The operator applies a downward force on the lower leg or popliteal fossa while using the ankle to control rotation until reduction in achieved [25].

A notable complication of closed reduction and one that every operator must be cautious to avoid is ipsilateral femoral neck fractures. If the reduction appears to be beyond the skill range of the operator, consider consulting an orthopedic surgeon for expert reduction or advice.

Regardless of the technique used for reducing the following applies:

- Assess the stability of the hip after reduction as well as leg length comparison to ensure the hip is reduced.

- Utilize x-ray for proof of reduction.

- For native hip dislocations, obtain a post-reduction CT scan to rule out associated injuries.

- If applicable, educate the patient on protected weight-bearing for 4 to 6 weeks.

Operative Management

Indications for open reductions:

- Failed closed reduction attempts.

- Femoral neck fracture (even if undisplaced).

- Noncongruent reduction ( due to incarcerated bony fragment or soft tissue obstruction)

- An associated acetabular or femoral head fracture that wil require fixation.

Open reductions allows removal of associated incarcerated bony fragments or fixation of associated fractures either the proximal femur or the acetabulum. Arthroscopy can also be used in the expert hands to remove intra-articular loose bodies and assess and repair soft tissue structures.

Approaches for open reductions of a dislocated hip either Kocher-Langenbeck (posterior) approach or Smith-Peterson (anterior) approach.

Differential Diagnosis

- Femoral head avascular necrosis

- Femur injuries and fractures

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- Traumatic hip subluxation

Staging

The Thompson and Epstein is a classfication system for posterior dislocation of the hip [26].

- I With or without a minor fracture.

- II With a large single fracture of the posterior acetabular rim.

- III With comminution of the acetabular ring.

- IV With a fracture of the acetabular floor.

- V With a fracture of the femoral head.

Type V dislocations were sub-classified according to Pipkin [27].

- I Fracture below the fovea; not involving weight-bearing surface of the head.

- II Fracture above the fovea; involving weight-bearing surface of the head.

- III Type I or II fracture with associated femoral neck fracture.

- IV Type I or II fracture with associated acetabulum fracture.

Prognosis

Simple dislocations have better outcome and quicker functional recovery, whilst the more complex the dislocation the higher the incidence of complications. There are several prognostic factors. The most important one is the time lapse between the injury and reduction. Better results were achieved with early reduction [28]. Other prognostic factors include fracture-dislocation type, congruency and stability of of the hip joint post reduction and severity of trauma [29].

Complications

The following is a list of complications that can develop after posterior hip dislocation:

- Avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

- Chondrolysis.

- Post-traumatic arthritis with increased incidence of post complex dislocations.

- Sciatic nerve injury.

- Heterotopic ossification.

- Recurrent dislocation.

It was noted that the incidence of complications was higher in Thompson-Epstein type IV [30]. Therefore counseling such patients regarding the prognosis and possible complications might increase patient's satisfaction. There is an increased incidence of avascular necrosis and post-traumatic arthritis with increased severity of trauma. Incidence was higher in hips reduced after 12 hours in comparison with hips reduced before 12 hours [31]. In the literature, the reported incidence of sciatic nerve injury is approximately 10% in adults and 5% in children. Usually, the peroneal branch is injured and partial recovery occurs in at least 60% to 70% of patients. There is no association between the type of injury or treatment and subsequent recovery [32].

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

A successfully reduced hip requires rest, ice, anti-inflammatory, and narcotic medications during the post-reduction acute phase. Weight-bearing is advised based on the type of dislocation. In type I posterior dislocations, patients are allowed to weight bear as early as pain allows. In type II to V dislocations, protected weight-bearing for 4 - 6 weeks is recommended. Complex dislocations with associated fractures and/or instability may require an abduction brace postoperatively. Abduction brace keeps the hip in abduction and slight external rotation, whilst allowing controlled flexion and extension. One week after reduction, patient can start pendulum exercises and passive range of motion exercises. This should be followed by more advanced exercises e.g. upright knee raise and resistive hip abduction. More detailed instructions should be provided by the physiotherapist.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Most posterior hip dislocations occur from traumatic events. Often an attempt will be made to reduce the hip in the emergency department. It is important for the pharmacist to provide and assist with adequate pain relief while the orthopedic nurse and clinicians collaborate to reduce the dislocation. an interprofessional team approach will result in the best care of the patient.