Introduction

Glycolysis is a metabolic pathway and an anaerobic energy source that has evolved in nearly all types of organisms. Another name for the process is the Embden-Meyerhof pathway, in honor of the major contributors towards its discovery and understanding.[1] Although it doesn't require oxygen, hence its purpose in anaerobic respiration, it is also the first step in cellular respiration. The process entails the oxidation of glucose molecules, the single most crucial organic fuel in plants, microbes, and animals. Most cells prefer glucose (although there are exceptions, such as acetic acid bacteria that prefer ethanol). In glycolysis, 2 ATP molecules are consumed, producing 4 ATP, 2 NADH, and 2 pyruvates per glucose molecule. The pyruvate can be used in the citric acid cycle or serve as a precursor for other reactions.[2][3][4]

Fundamentals

Glycolysis ultimately splits glucose into two pyruvate molecules. One can think of glycolysis as having two phases that occur in the cytosol of cells. The first phase is the "investment" phase due to its usage of two ATP molecules, and the second is the "payoff" phase. These reactions are all catalyzed by their own enzyme, with phosphofructokinase being the most essential for regulation as it controls the speed of glycolysis.[1]

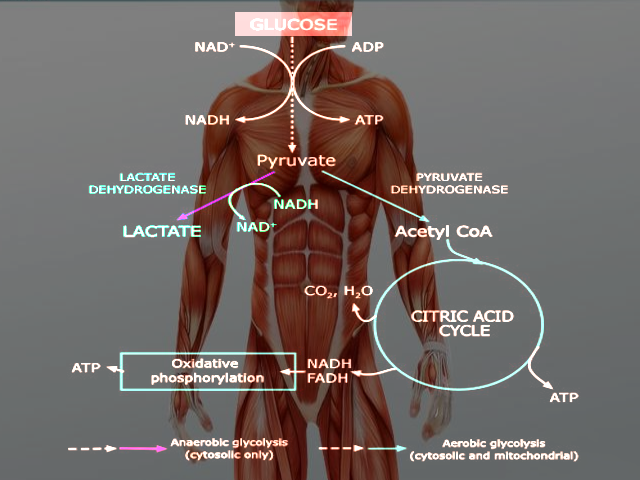

Glycolysis occurs in both aerobic and anaerobic states. In aerobic conditions, pyruvate enters the citric acid cycle and undergoes oxidative phosphorylation leading to the net production of 32 ATP molecules. In anaerobic conditions, pyruvate converts to lactate through anaerobic glycolysis. Anaerobic respiration results in the production of 2 ATP molecules.[5] Glucose is a hexose sugar, meaning it is a monosaccharide with six carbon atoms and six oxygen atoms. The first carbon has an attached aldehyde group, and the other five carbons have one hydroxyl group each. During glycolysis, glucose ultimately breaks down into pyruvate and energy; a total of 2 ATP is derived in the process (Glucose + 2 NAD+ + 2 ADP + 2 Pi --> 2 Pyruvate + 2 NADH + 2 H+ + 2 ATP + 2 H2O). The hydroxyl groups allow for phosphorylation. The specific form of glucose used in glycolysis is glucose 6-phosphate.

Cellular Level

Glycolysis occurs in the cytosol of cells. Under aerobic conditions, pyruvate derived from glucose will enter the mitochondria to undergo oxidative phosphorylation. Anaerobic conditions result in pyruvate staying in the cytoplasm and being converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase.[5]

Molecular Level

Glucose first converts to glucose-6-phosphate by hexokinase or glucokinase, using ATP and a phosphate group. Glucokinase is a subtype of hexokinase found in humans. Glucokinase has a reduced affinity for glucose and is found only in the pancreas and liver, whereas hexokinase is present in all cells. Glucose 6-phosphate is then converted to fructose-6-phosphate, an isomer, by phosphoglucose isomerase. Phosphofructose-kinase then produces fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, using another ATP molecule. Dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate are then created from fructose-1,6-bisphosphate by fructose bisphosphate aldolase. DHAP will be converted to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate by triosephosphate isomerase, where now the two glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate molecules will continue down the same pathway. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate will become oxidized in an exergonic reaction into 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, reducing an NAD+ molecule to NADH and H+. 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate will then turn into 3-phosphoglycerate with the help of phosphoglycerate kinase, along with the production of the first ATP molecule from glycolysis. 3-phosphoglycerate will then convert, with the help of phosphoglycerate mutase, into 2-phosphoglycerate. With the release of one molecule of H2O, Enolase will make phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) from 2-phosphoglycerate. Due to the unstable state of PEP, pyruvate kinase will facilitate its loss of a phosphate group to create the second ATP in glycolysis. Thus, PEP will then undergo conversion to pyruvate.[6][7][8]

Function

Glycolysis occurs in the cytosol of the cell. It is a metabolic pathway that creates ATP without the use of oxygen but can occur in the presence of oxygen. In cells that use aerobic respiration as the primary energy source, the pyruvate formed from the pathway can be used in the citric acid cycle and go through oxidative phosphorylation to undergo oxidation into carbon dioxide and water. Even if cells primarily use oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis can serve as an emergency backup for energy or as the preparation step before oxidative phosphorylation. In highly oxidative tissue, such as the heart, pyruvate production is essential for acetyl-CoA synthesis and L-malate synthesis. It serves as a precursor to many molecules, such as lactate, alanine, and oxaloacetate.[8]

Glycolysis precedes lactic acid fermentation; the pyruvate made in the former process serves as the prerequisite for the lactate made in the latter process. Lactic acid fermentation is the primary source of ATP in animal tissues with low metabolic requirements and little to no mitochondria. In erythrocytes, lactic acid fermentation is the sole source of ATP, as they lack mitochondria and mature red blood cells have little demand for ATP. Another part of the body that relies entirely or almost entirely on anaerobic glycolysis is the eye's lens, which is devoid of mitochondria, as their presence would lead to light scattering.[8]

Though skeletal muscles prefer to catalyze glucose into carbon dioxide and water during heavy exercise where oxygen is inadequate, the muscles simultaneously undergo anaerobic glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation.[8]

Regulation

Glucose

The amount of glucose available for the process regulates glycolysis, which becomes available primarily in two ways: regulation of glucose reuptake or regulation of the breakdown of glycogen. Glucose transporters (GLUT) transport glucose from the outside of the cell to the inside. Cells containing GLUT can increase the number of GLUT in the cell's plasma membrane from the intracellular matrix, therefore increasing the uptake of glucose and the supply of glucose available for glycolysis. There are five types of GLUTs. GLUT1 is present in RBCs, the blood-brain barrier, and the blood-placental barrier. GLUT2 is in the liver, beta-cells of the pancreas, kidney, and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GLUT3 is present in neurons. GLUT4 is in adipocytes, heart, and skeletal muscle. GLUT5 specifically transports fructose into cells. Another form of regulation is the breakdown of glycogen. Cells can store extra glucose as glycogen when glucose levels are high in the cell plasma. Conversely, when levels are low, glycogen can be converted back into glucose. Two enzymes control the breakdown of glycogen: glycogen phosphorylase and glycogen synthase. The enzymes can be regulated through feedback loops of glucose or glucose 1-phosphate, or via allosteric regulation by metabolites, or from phosphorylation/dephosphorylation control.[8]

Allosteric Regulators and Oxygen

As described before, many enzymes are involved in the glycolytic pathway by converting one intermediate to another. Control of these enzymes, such as hexokinase, phosphofructokinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and pyruvate kinase, can regulate glycolysis. The amount of oxygen available can also regulate glycolysis. The “Pasteur effect” describes how the availability of oxygen diminishes the effect of glycolysis, and decreased availability leads to an acceleration of glycolysis, at least initially. The mechanisms responsible for this effect include allosteric regulators of glycolysis (enzymes such as hexokinase). The “Pasteur effect” appears to mostly occur in tissue with high mitochondrial capacities, such as myocytes or hepatocytes. Still, this effect is not universal in oxidative tissue, such as pancreatic cells.[8]

Enzyme Induction

Another mechanism for controlling glycolytic rates is transcriptional control of glycolytic enzymes. Altering the concentration of key enzymes allows the cell to change and adapt to alterations in hormonal status. For example, increasing glucose and insulin levels can increase hexokinase and pyruvate kinase activity, therefore increasing the production of pyruvate.[8]

PFK-1

Fructose 2,6-bisphosphate is an allosteric regulator of PFK-1. High levels of fructose 2,6-bisphosphate increase the activity of PFK-1. Its production occurs through the action of phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK-2). PFK-2 has both kinase and phosphorylase activity and can transform fructose 6 phosphates to fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and vice versa. Insulin dephosphorylates PFK-2, activating its kinase activity, which increases fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and subsequently activates PFK-1. Glucagon can also phosphorylate PFK-2, which activates phosphatase, transforming fructose 2,6-bisphosphate back to fructose 6-phosphate. This reaction decreases fructose 2,6-bisphosphate levels and decreases PFK-1 activity.[8]

Mechanism

Glycolysis Phases

Glycolysis has two phases: the investment phase and the payoff phase. The investment phase is where there is energy, as ATP, is put in, and the payoff phase is where the net creation of ATP and NADH molecules occurs. A total of 2 ATP goes into the investment phase, with the production of 4 ATP resulting in the payoff phase; thus, there is a net total of 2 ATP. The steps by which new ATP is created have the name of substrate-level phosphorylation.[8]

Investment Phase

In this phase, there are two phosphates added to glucose. Glycolysis begins with hexokinase phosphorylating glucose into glucose-6 phosphate (G6P). This step is the first transfer of a phosphate group and where the consumption of the first ATP takes place. Also, this is an irreversible step. This phosphorylation traps the glucose molecule in the cell because it cannot readily pass the cell membrane. From there, phosphoglucose isomerase isomerizes G6P into fructose 6-phosphate (F6P). Then, phosphofructokinase (PFK-1) adds the second phosphate. PFK-1 uses the second ATP and phosphorylates the F6P into fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. This step is also irreversible and is the rate-limiting step. In the following step, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate undergoes lysis into two molecules, which are substrates for fructose-bisphosphate aldolase to convert it into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). DHAP is turned into G3P by triosephosphate isomerase. DHAP and G3p are in equilibrium with each other, meaning they transform back and forth.[8]

Payoff Phase

It is critical to remember that there are a total of two 3-carbon sugars for every one glucose at the beginning of this phase. The enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase metabolizes the G3P into 1,3-diphosphoglycerate by reducing NAD+ into NADH. Next, the 1,3-diphosphoglycerate loses a phosphate group through phosphoglycerate kinase to make 3-phosphoglycerate and creates an ATP through substrate-level phosphorylation. At this point, there are 2 ATP produced, one from each 3-carbon molecule. The 3-phosphoglycerate turns into 2-phosphoglycerate by phosphoglycerate mutase, and then enolase turns the 2-phosphoglycerate into phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP). In the final step, pyruvate kinase turns PEP into pyruvate and phosphorylates ADP into ATP through substrate-level phosphorylation, thus creating two more ATP. This step is also irreversible. Overall, the input for 1 glucose molecule is 2 ATP, and the output is 4 ATP, 2 NADH, and 2 pyruvate molecules.[8]

In cells, NADH must recycle back to NAD+ to permit glycolysis to keep running. Absent NAD+, the payoff phase will come to a halt, resulting in a backup in glycolysis. In aerobic cells, NADH recycles back into NAD+ by way of oxidative phosphorylation. In anaerobic cells, it occurs through fermentation. There are two types of fermentation: lactic acid and alcohol fermentation.[8]

Clinical Significance

Pyruvate kinase deficiency is an autosomal recessive mutation that causes hemolytic anemia. There is an inability to form ATP and causes cell damage. Cells become swollen and are taken up by the spleen, causing splenomegaly. Signs and symptoms include jaundice, icterus, elevated bilirubin, and splenomegaly.[9][10][11]

Arsenic poisoning also prevents ATP synthesis because arsenic takes the place of phosphate in the steps of glycolysis.[12]