Continuing Education Activity

Gardnerella vaginalis is a predominant anaerobic bacterium responsible for causing bacterial vaginosis (BV) in women. Although G vaginalis is a natural component of the normal vaginal flora, an excessive proliferation of this bacterium can lead to BV, the primary cause of abnormal vaginal discharge or vaginitis. Gardnerella infection poses distinctive challenges due to its far-reaching implications on women's reproductive health, susceptibility to sexually transmitted diseases, and potential to give rise to complications during pregnancy. This activity comprehensively reviews the evaluation and treatment of BV caused by an overgrowth of G vaginalis. Furthermore, this activity elucidates the crucial role of the interprofessional team in effectively treating patients afflicted by this condition.

Objectives:

Differentiate between Gardnerella vaginalis–associated bacterial vaginosis and other vaginal infections based on clinical presentation and laboratory findings.

Implement evidence-based treatment strategies for bacterial vaginosis, considering the role of Gardnerella vaginalis and other implicated microorganisms.

Apply knowledge of the microbiology and pathophysiology of Gardnerella vaginalis to educate patients about Gardnerella infections and recurrence, as well as guide treatment decisions.

Collaborate with the interprofessional team to share insights and optimize the diagnosis and management of initial and recurrent Gardnerella infections.

Introduction

Gardnerella vaginalis is a predominant anaerobic bacterium that is a natural component of the normal vaginal flora.[1] Gardnerella was named after Hermann L. Gardner, the scientist who discovered the bacterium in 1955. Normally, the Lactobacillus species predominates the vaginal flora. However, when organisms such as Gardnerella overgrow and assume dominance, this imbalance results in bacterial vaginosis (BV).

BV is a condition that causes abnormal vaginal discharge and involves a polymicrobial overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria within the vaginal environment. BV is associated with infertility, preterm birth, postpartum endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and an increased risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[1][2]

Etiology

The exact etiology of BV resulting from the proliferation of Gardnerella bacteria remains unknown.[3] Although G vaginalis is not considered contagious, the extent of its transmissibility remains incompletely understood.[4] The transmission of this bacterium among individuals through sexual intercourse could disrupt the natural bacterial balance within the vagina. Such an imbalance could lead to the onset of BV.[4] In most cases, BV is caused by a reduced population of normal Lactobacillus species that produce lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide. This decrease paves the way for an excessive growth of opportunistic, anaerobic bacteria, including G vaginalis.[4]

In the past, BV was referred to as G vaginitis due to the belief that this bacterium was responsible for the condition.[1] However, the term BV, which is more contemporary, effectively highlights that various naturally occurring anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal ecosystem might undergo excessive proliferation. This imbalance in the vaginal environment serves as the root cause of BV.

Research has identified G vaginalis in the vaginal tracts of as many as 50% of asymptomatic women. This observation has led to the assumption that Gardnerella could potentially be a component of the normal vaginal flora. Various factors that might contribute to the development of BV include frequent baths, douching, smoking, engaging in multiple sexual partners, using over-the-counter intravaginal hygiene products, experiencing severe stress, and increased frequency of sexual intercourse. BV might also be more prevalent among women who do not frequently change their underwear.[5]

Epidemiology

BV is the most prevalent vaginal infection in women of reproductive age, with estimated occurrences ranging from 5% to 70%.[6] The prevalence of BV among women fluctuates from 20% to 60% across various countries. In the United States, BV rates are approximately 30%.[7] BV rates are lowest in Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe.[3] BV exhibits a higher prevalence among black women compared to white women.

In addition, it is more frequently encountered in women with multiple sexual partners.[5] Gardnerella has consistently been identified as a significant pathogen in BV, indicating a notable prevalence of Gardnerella in these populations.[6]

Pathophysiology

Although the exact pathophysiology is uncertain, the prevailing notion is that most BV infections initiate with a biofilm formed by G vaginalis. This biofilm subsequently provides a conducive environment for the proliferation of other opportunistic bacteria.[8] G vaginalis produces vaginolysin, a pore-forming toxin affecting human cells. Vaginolysin is a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin that initiates complex signaling cascades that trigger target cell lysis and enhance Gardnerella’s virulence. Furthermore, this bacterium is often accompanied by protease and sialidase enzyme activities.

Gardnerella has the necessary virulence factors that facilitate its adherence to host epithelial cells, enabling it to compete with Lactobacillus for dominance within the vaginal environment effectively. The symptoms of BV are believed to arise from the proliferation of usually dormant vaginal anaerobes that establish symbiotic relationships with Gardnerella.[9]

Histopathology

G vaginalis is a coccobacillus that lacks spore formation and motility.[4] This bacterium can be cultivated to form small, circular, gray colonies on both chocolate and human blood bilayer agar media with Tween 80 (HBT medium) agar. A selective medium for Gardnerella is colistin-oxolinic acid blood sugar. Although Gardnerella has a thin, gram-positive cell wall, it is regarded as gram-variable as its appearance can oscillate between gram-positive and gram-negative due to the fluctuating visibility of its thin cell wall.[10]

For approximately 40 years, G vaginalis stood as the only recognized species within its Gardnerella genus. More recently, as many as 13 new species have been identified, including G leopoldii, G piotii, and G swidsinskii.[2]

History and Physical

Women harboring G vaginalis are typically asymptomatic unless an imbalance occurs between Gardnerella and Lactobacillus populations.[11] Approximately 50% of women affected by BV experience symptoms.[3] Symptomatic women often report a malodorous vaginal discharge that intensifies following sexual intercourse. Itching may also be a concurrent complaint.

Evaluation

BV is diagnosed using either Amsel criteria or the Nugent score. Amsel criteria are commonly used in the clinical setting and require the fulfillment of at least 3 out of 4 specified criteria.

Amsel Criteria

Amsel Criteria include the following indicators that collectively aid in the accurate assessment of the condition:

- Homogenous, thin, grayish-white vaginal discharge that coats the vaginal walls evenly

- Detection of ≥20% clue cells on a wet mount

- Vaginal pH ≥4.5

- Positive whiff test

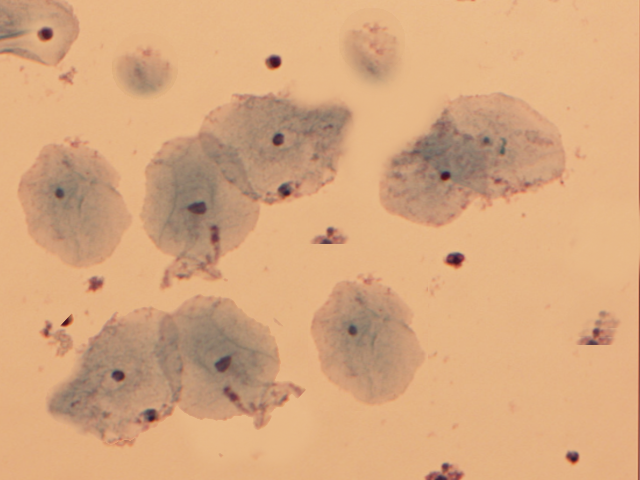

Clue cells are vaginal epithelial cells that are covered with rod-shaped bacteria (see Image. Clue Cells).[9] A drop of sodium chloride solution is placed on the wet-mount slide containing the vaginal specimen, and upon microscopic examination, this technique reveals the distinctive clue cells. The whiff test is performed by adding a small amount of potassium hydroxide onto the microscopic slide containing the vaginal discharge. The positive whiff test is determined when a distinctive fishy odor becomes perceptible.[12]

The Nugent scoring system employs a microscopic examination and gram-stain technique to evaluate the presence of vaginal bacteria, assigning a numerical score ranging from 0 to 10. A higher score indicates a more significant presence of bacteria associated with BV.[13] Nugent score is primarily utilized within the realm of research.

Generally, point-of-care tests are not commonly utilized in clinical settings due to their high cost. Instead, clinical practitioners often rely on commercial molecular diagnostic assays for assessment. These tests enable the quantification of bacteria and exhibit a sensitivity ranging from 90.5% to 96.7% and a specificity of 85.8% to 95%.[5] Since introducing the rapid identification method in 1982, isolating 91.4% of Gardnerella strains using a micromethod involving starch, raffinose fermentation, and hippurate hydrolysis has become possible.[14]

Treatment / Management

Treatment is not necessary for asymptomatic Gardnerella colonization. Currently, insufficient evidence supports the notion that treating asymptomatic BV reduces adverse patient outcomes.[13] Approximately 30% of BV cases are known to resolve without treatment.[1] However, if a patient experiences distress due to the symptoms of BV, it is recommended to pursue treatment using either oral or vaginal medication, as detailed below.

In 2017, secnidazole was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for single-dose oral treatment for BV.[13] Although secnidazole, a next-generation 5-nitroimidazole, has a longstanding history of use in treating both parasitic and bacterial infections, it has recently been approved by the FDA for BV treatment in the United States.[15]

Initial treatment for BV demonstrates notable efficacy, as cure rates within 1 month typically range from 80% to 90%.[3] Unfortunately, recurrence may occur in as many as 80% of women within 9 months following initial treatment.[1][16] If a patient experiences recurrent symptoms, a second course of antibiotics is generally prescribed.[1] A Cochrane review conducted in 2009 yielded tentative yet inconclusive evidence regarding the use of probiotics for treating and preventing BV.[17] Importantly, it is worth noting that there is no universally established, strict definition for recurrent BV.

Treatment Regimens for BV

The treatment regimens used to manage the condition are listed below when treating BV.

Metronidazole: This medication is administered orally at 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.

Metronidazole intravaginal gel: This gel is used at a 0.75% strength, and the recommended regimen involves applying 5 g of the gel intravaginally once daily for 5 days.

Clindamycin intravaginal cream: This cream is used at a 2% strength, and the recommended dosage involves applying 5 g of the cream nightly for 7 days.

Alternate Treatment Regimens for BV

The alternative regimens for addressing BV are listed below.

Clindamycin intravaginal ovules: This medication is administered as 100 mg ovules, taken intravaginally on a nightly basis for 3 days.

Clindamycin oral tablets: This medication is prescribed at 300 mg, taken orally twice daily for 7 days.

Tinidazole: This medication can be taken orally either as a 5-day course at a dosage of 1 g daily or a shorter 2-day treatment at 2 g daily.

Secnidazole oral granules: This medication is administered as a single dose of 2 g of oral granules.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for BV includes atrophic vaginitis, candidiasis, cervicitis, chlamydia, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, gonorrhea, herpes simplex, and trichomoniasis.

A thorough pelvic examination can effectively refine the differential diagnosis and exclude other similar conditions, such as vaginal candidiasis, trichomonas vaginitis, or herpes simplex virus. A speculum exam aids in the identification of cervicitis, while a wet mount of the vaginal discharge assists in discerning the presence of candidiasis or trichomoniasis.[1] Furthermore, additional cervical swab cultures can be dispatched to assess for chlamydia and gonorrhea.[18]

Prognosis

Most uncomplicated cases of BV resolve with treatment. However, recurrences are not uncommon due to the frequent failure of antibiotic treatment to restore the vagina to its typical Lactobacillus-dominated state. The biofilms of Gardnerella bacteria create a shield that helps prevent metronidazole from penetrating.[7] Within 3 months following treatment, approximately 80% of women may experience a recurrence of BV. In the past decade, there has been a growing number of reports regarding BV strains that are resistant to conventional treatments and do not respond to them.

In a recent randomized controlled trial, a powder containing the naturally occurring live strain Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 was used. Following metronidazole treatment, women utilized the intravaginal powder to reduce the recurrence of BV. The regimen involved using the powder 4 times daily during the first week, followed by twice-weekly use for 10 weeks. The use of lactobacillus powder after BV treatment with metronidazole significantly lowered the recurrence rate of BV up to 24 weeks after the treatment. Notably, this approach has not yet received FDA approval.[19] Several alternative vaginal products are currently under investigation to enhance BV recurrence rates.

BV has been associated with an increased risk of contracting STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas, herpes, human papillomavirus (HPV), and HIV. As Gardnerella damages the vaginal epithelium, it concurrently elevates the risk of HPV infection.[3] In addition, BV may contribute to tubal infertility and difficulties in conceiving with assisted reproductive techniques, but a causal relationship has not been established.[13] The concept of treating heterosexual partners with antibiotics as a means to prevent recurrent BV is still under investigation, but it is not currently recommended as a routine strategy.[20]

Intravaginal boric acid has also been recommended for managing recurrent BV. Although this regimen lacks FDA approval, the existing evidence indicates the safety of intravaginal boric acid usage in non-pregnant women. The recommended dosage of intravaginal boric acid for women is 600 mg, administered intravaginally twice weekly to prevent BV. The use of boric acid vaginal suppositories should be avoided during pregnancy, and it should not be taken orally.[20]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), multiple recurrences of BV can be managed using any 1 of the following treatment regimens:

- Metronidazole gel 0.75% or metronidazole vaginal suppository 750 mg administered twice weekly for over 3 months.

- An oral nitroimidazole course comprising 500 mg metronidazole or tinidazole, taken twice daily for 7 days, followed by 600 mg intravaginal boric acid, administered daily for 21 days, and ongoing suppressive treatment with 0.75% metronidazole gel, applied twice weekly for 4 to 6 months.

- A monthly regimen involving oral administration of 2 g metronidazole taken concurrently with 150 mg oral fluconazole.

Complications

The complications associated with BV are listed below.

- Increased risk of endometritis and salpingitis.

- Elevated risk of postsurgical infections.

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes include premature labor, premature rupture of membranes, and postpartum endometritis.

- Development of pelvic inflammatory disease.

- Possibility of neonatal meningitis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Providing patient education about Gardnerella can facilitate the identification of symptoms and subsequently enable timely treatment to mitigate potential complications associated with BV. Although the exact cause of the increased pH and bacterial overgrowth leading to BV remains incompletely understood, there are preventive measures that women can adopt to minimize the overgrowth of G vaginalis. Healthcare providers should offer comprehensive education to women regarding the risk factors associated with BV, which encompass, but are not limited to, engaging in multiple sexual partners, douching, lack of condom usage, smoking, and having female sexual partners. By reducing these risks, a resultant decrease in BV incidence could potentially contribute to lowering the acquisition of other STIs and mitigating complications that may arise from G vaginalis overgrowth.

Pearls and Other Issues

Untreated BV can elevate the risk of complications during pregnancy and increase susceptibility to STIs, including HIV.[18] Data also indicate an association between BV and both tubal factor infertility and pelvic inflammatory disease. During pregnancy, BV has been associated with an increased risk of premature birth, miscarriage, chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes, and postpartum endometritis.[21] However, despite these associations, routine screening for BV during pregnancy is not recommended.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Gardnerella is a common genital tract overgrowth often encountered by emergency department physicians, nurse practitioners, family medicine clinicians, internists, and gynecologists. BV significantly diminishes the quality of life for women affected by it.[22] Asymptomatic Gardnerella colonization does not necessitate treatment, as nearly 30% of cases resolve spontaneously. Physicians, advanced care practitioners, and nurses must know this caveat to prevent unnecessary antibiotic overtreatment. While all symptomatic patients require treatment, it is noteworthy that recurrences are prevalent even after the initial cure. Although BV is not classified as an STI, healthcare professionals are responsible for educating patients about the significance of practicing safe sex, avoiding multiple sexual partners, and utilizing barrier protection methods. The enhancement of patient safety and improvement in patient outcomes can be achieved through interprofessional communication and collaboration.

Untreated BV can increase the risk of pregnancy complications and STIs, including HIV.[18] Data also suggest an association between BV and tubal factor infertility and pelvic inflammatory disease.[21] The recurrence of BV is distressing, as it has been linked to unfavorable social, emotional, and sexual impacts. BV maintains its economic strain on the healthcare system, necessitating multiple clinic visits and recurrent antibiotic utilization for patients.[19]