Continuing Education Activity

Gait, the pattern of walking or running, is a fundamental aspect of human movement, and disruptions to this pattern can signal underlying health issues across various medical specialties. Gait disturbances are described as any deviations from normal walking or gait. These deviations occur in the intricate interplay of muscles, joints, and neurological pathways and present challenges that extend beyond mere physical inconvenience. Gait disturbances encompass a spectrum of abnormalities, ranging from subtle alterations in rhythm and coordination to pronounced disturbances indicative of underlying pathology. Due to their different clinical presentations, a high index of suspicion is required. The etiology can be determined through clinical presentation and diagnostic testing. Furthermore, this entity can be subdivided into episodic and chronic disturbances. Gait disturbances have a tremendous impact on patients, particularly on quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.

This course is designed to provide healthcare professionals with a thorough understanding of gait disturbances, encompassing their etiology and assessment. The intricate interplay between musculoskeletal, neurological, and systemic factors is explored. Participants will gain valuable insights into the diagnostic process, learning to recognize subtle signs and symptoms indicative of underlying pathology. This activity will also address the diverse array of treatment strategies available for optimizing gait function, considering the unique needs and preferences of individual patients across the lifespan. Armed with a comprehensive understanding of this complex topic, participants will be better equipped to improve patient outcomes, work as interprofessional team members, and enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by gait abnormalities.

Objectives:

Identify the pathophysiology of gait disturbance.

Implement appropriate diagnostic tests and assessment tools to accurately evaluate gait abnormalities.

Apply evidence-based treatment modalities tailored to the specific etiology and severity of gait disturbances.

Collaborate with an interprofessional healthcare team, including physical and occupational therapists, neurologists, and orthopedic specialists, to optimize care for patients affected by gait disturbances.

Introduction

Gait disturbances are described as any deviations from normal walking or gait. Numerous etiologies cause these disturbances. Due to their different clinical presentations, a high index of suspicion is required. The etiology can be determined through the clinical presentation and diagnostic testing. Gait problems can be subdivided into episodic and chronic disturbances.[1] Episodic disturbances include those abnormalities that occur suddenly, which the patient has not adapted to, and are a frequent cause of complications like unexpected falls. Examples of episodic disturbances include freezing gait, festinating gait, and disequilibrium.[2][3] Most other gait disturbances belong to the chronic category. Continuous or chronic gait disturbances are those the patient has adapted to due to the chronicity of the neurological dysfunction.

Neurological causes are more common than non-neurological causes. Sensory ataxia caused by polyneuropathy, parkinsonism, subcortical vascular encephalopathy, and dementia are among the most common neurological causes.[4][5] Hip and knee osteoarthritis, causing pain and limited motion, are common non-neurological causes of gait disorders.[6][7] Gait disturbances have a tremendous impact on patients, especially on the quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.

Etiology

Understanding the diverse etiology of gait disturbances is paramount for clinicians in effectively diagnosing and managing these conditions. Gait disturbances can arise from a wide range of neurological, musculoskeletal, and systemic disorders, each with unique pathophysiological mechanisms influencing gait patterns and function. Etiologies include the following:

Neurologic Disease

Numerous diseases affect the central and peripheral nervous systems, ultimately affecting gait. Due to the intricacies in the communications between these 2 systems, even subtle changes can lead to gait disturbances. Disease states, including Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, and normal pressure hydrocephalus, can alter neurocognitive functions to the point that walking can become a difficult task. The weakness of the hip and lower extremity muscles commonly causes gait disturbances. Cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, Charcot Marie Tooth disease, ataxia-telangiectasia, spinal muscular atrophy, peroneal neuropathy, and microvascular white-matter disease all cause significant gait disabilities.[8]

Electrolyte Imbalances

Electrolyte disorders, including hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia, can cause gait disorders. Hyponatremia, the most common, can lead to severe neurological symptoms that affect gait.[9] Electrolyte balance is crucial to maintaining the proper musculoskeletal function, which contributes directly to normal gait.

Vitamin Deficiencies

Common vitamin deficiencies contributing to gait imbalances include folate, vitamin B12, vitamin E, and copper deficiency.[10][11] The deficiency of these vitamins has been shown to cause neurological dysfunctions, which impede proper gait. Vitamin B12 deficiency, which causes subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, can lead to numbness and paresthesia, which ultimately affect gait.[12][13]

Psychiatric Causes

Anxiety, depression, and malingering have to be excluded.

Other Etiologies

Pain, vascular, traumatic, autoimmune, inflammatory, metabolic, neoplastic, paraneoplastic, and tabes dorsalis may be involved.

Epidemiology

Studies have demonstrated that gait disturbances occur as an individual ages, stemming from neurological and non-neurological causes. Studies have shown that while 85% of individuals aged 60 have a normal gait, by the time they reach the age of 85 years, only 20% maintain a normal gait.[6][14] Gait disturbances are not commonly seen in the younger population unless they stem from a developmental or musculoskeletal etiology.[15] No differences in incidence or prevalence between males and females have been found. Men have more neurological gait problems, while women have more non-neurologic gait problems.[16]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of gait disturbances is complex. The normal physiology must be initially delineated to understand how deviations from this norm contribute to gait disturbances. Normal gait involves a gait cycle with a stance phase and a swing phase. When 1 limb swings, the contralateral limb stances. The duration in each phase varies depending on the velocity of the gait and can be altered in different gait disturbances. Normal gait is a combination of central nervous system control and peripheral nervous system feedback.

At rest, in the erect position, an individual relies on sensory feedback to maintain a center of gravity.[17] Postural control is an essential component of gait.[18] It depends on the integration of sensory inputs and spatiotemporal coordination. The integration of visual, vestibular, and somatosensory information influences postural control. With age, these inputs are reduced, negatively affecting normal gait.

Gait occurs in a cycle from initiation of the first leg heel strike to termination with the next heel strike to propel the movement of an individual.[19] Hip flexion changes the limb from a standing position to a swing position. The central nervous system interprets the position of an individual and helps balance the individual. When any part of the central nervous is diseased, this can lead to improper processing and an unsteady gait because the center of balance is thrown off. Integration of the spinal interneuronal network with the brainstem, cerebral cortex (motor and premotor), and cerebellum centers produces a normal gait.[20] Cerebellar ataxia produces postural deficits in a quiet stance before voluntary limb movements are initiated.[21]

History and Physical

The typical presentation of gait disturbances may be apparent on the clinic exam. However, it may be subclinical. Therefore, the entire clinical picture must be taken into account. An extensive patient history is required. Social history, as well as medical history, is critical in the evaluation. Understanding how long the symptoms have been present and determining whether the onset was sudden or insidious is essential. Merely taking a patient's history can help narrow down the etiology of the gait disturbance.[22] Understanding different aspects of a patient's history is important, specifically, their diet, ability to perform daily activities of living, and physical limitations.

Clinical examination should include assessing the following:

- Standing

- Posture

- Stance (narrow or wide)

- Initiation of gait

- Walking

- Step length

- Speed

- Arm swing

- Freezing

- Turning

- Tandem gait

- Romberg test

- Blind walk

- Backward walking

- Fast turning

- Heel walking

- Toe walking

- Running (if able to perform)

The examination can separate gait disturbances into 2 categories: musculoskeletal or neuromuscular (lower and upper motor neurons).

Musculoskeletal

1. Antalgic gait: an abnormal pattern of walking secondary to pain that ultimately causes a limp, whereby the stance phase is shortened relative to the swing phase.

- Cause: pain

- Treatment: involves addressing the underlying cause

2. Vaulting gait: a compensatory mechanism that can be real or apparent. Common in children with limb length discrepancy.

- Cause: pelvic droop, decreased hip and knee flexion, ankle plantar flexion

- Treatment: shoe lift or surgery for limb difference >2 cm; no treatment needed otherwise

Neuromuscular

1. Trendelenburg gait: an abnormal gait with the pelvis dropping to the unaffected side.

- Cause: hip abductor weakness

- Treatment: gluteus medius strengthening

2. Posterior lurch gait: a backward trunk lean with a hyperextended hip during the stance phase of the affected limb.

- Cause: hip extensor weakness

- Treatment: gluteus maximus strengthening

3. Knee buckling: genu recurvatum—posterior capsule locks affected knee joint, hyperextending knee by forwarding trunk leading.

- Cause: knee extensor weakness

- Treatment: solid or hinged ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) and quadriceps strengthening

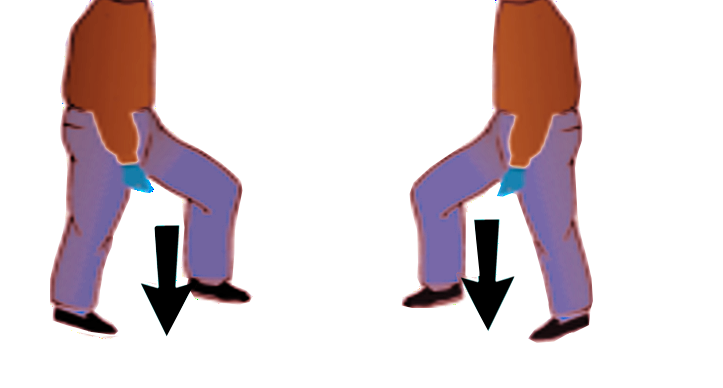

4. Steppage gait: inability to heel strike causing initial contact with toes (foot drop) (see Image. Steppage Gait).

- Cause: ankle dorsiflexion weakness

- Treatment: hinged or posterior leaf spring AFO and electrical stimulator

5. Calcaneal gait: knee flexion movement with excess tibial motion over the ankle during mid to late stance.

- Cause: ankle plantar flexor weakness

- Treatment: hinged or solid AFO to prevent buckling at the knee

6. Waddling gait: toe walking (posterior lurch and bilateral Trendelenburg).

- Cause: proximal muscle weakness

- Treatment: low-resistant strength training, aerobic exercise

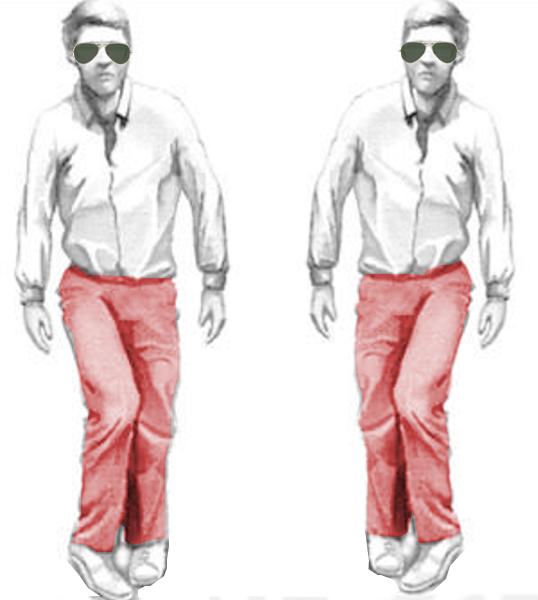

7. Scissor gait (crouched gait): found in individuals with cerebral palsy (see Image. Scissor Gait).

- Cause: prolonged neonatal hypoxia, brain injury during birth

- Treatment: supportive care

8. Ataxic gait: a broad-based, unsteady gait.

- Cause: cerebellar syndrome (alcohol, phenytoin, stroke, tumor, degenerative, inflammatory)

- Treatment: address the underlying cause

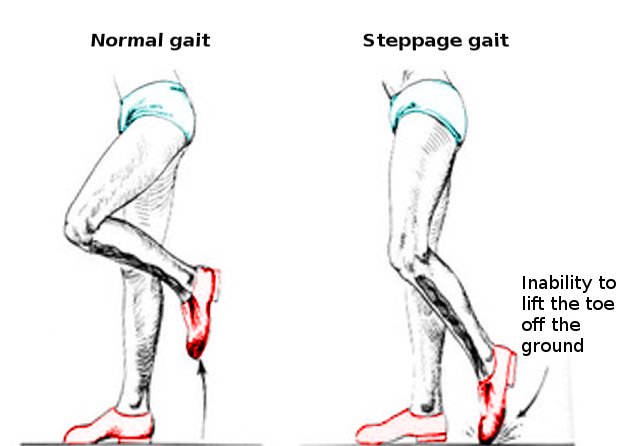

9. Sensory ataxic gait (stomping gait): Positive Romberg test. Seen in patients with vitamin B12 deficiency. The patients use visual control to compensate for the loss of proprioception (see Image. Stomping Gait Drawing).

10. Hemiparetic gait (hemispastic gait): gait is slow, with a broad base; knee and hip are extended during the swing phase, the paretic leg performs a lateral movement (circumduction).

- Cause: stroke, tumor, trauma, degenerative, inflammatory, vasculitis

- Treatment: address the underlying causes and supportive care

11. Festinating gait (shuffling gait): short stepped, hurrying, with weak arm swing, or naturally very slow (parkinsonian), in some patients with freezing and slow turning.

- Cause: Parkinson disease

- Treatment: dopamine agonist, dopamine precursors, and deep brain stimulation

12. Apraxic frontal gait (apractic or Bruns apraxia): gait ignition failure or with walking difficulty ('Marche' petit pas'). Bilateral frontal lobe lesions.

13. Hyperkinetic gait: found in patients with chorea, dystonia, and Wilson disease.

14. Freezing gait: seen in patients with Parkinson disease, typically occurs on turning or when approaching obstacles or narrow passages such as doors. Can fall easily.

15. Neurogenic claudication: found in patients with spinal stenosis, bending forward to relieve pressure, flexed position.

16. Intermittent claudication: seen in peripherovascular disease, the patient stops walking.

17. Myelopatic gait: a spastic, stiff gait.

18. Propulsive gait: the center of gravity is anterior to the body.

19. Magnetic gait: seen in normal pressure hydrocephalus, slow and unsteady turns, slow, broad-based, short-stepped, "stuck to the floor," or "glued to the floor" are phrases often used.

20. Paraspastic gait: the gait may appear stiff and insecure, narrow-based, stiff, toe-scuffing (spastic paraparesis).

- Cause: bilateral stroke, tumor, trauma, degenerative, inflammatory

- Treatment: address the underlying causes and supportive care

21. Myoclonic gait: short-lasting, involuntary jerks that result in joint movement.

22. Thalamic astasia: a fall backward or to the contralateral side while sitting or standing caused by thalamic lesions or strokes.

23. Higher-level gait disorders: seen in patients with microvascular white-matter disease, small steps, and disequilibrium due to alterations in the balance-locomotor circuits (cortex, brainstem, and cerebellum).[23]

24. Psychogenic gait: rare falls, bizarre walking, lack of persistence of a symptom or sign.

Evaluation

The evaluation of gait disturbances is a comprehensive process that requires a systematic approach to assess the underlying causes and functional impact on patients. Observation can provide tremendous feedback concerning the etiology of a patient's gait disturbance. It is essential to observe a patient's tendencies during gait cycles and identify where they are compensating. Testing of joint motion, joint pain, extremity force, and coordination is all necessary. Knee, ankle, and foot coordination must be precise for proper gait. Fall risk should be assessed in all patients.

Laboratory tests are particularly relevant to rule out metabolic disturbances or vitamin deficiencies.[22] A complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel can reveal most deficiencies. If the clinical suspicion is high enough, further laboratories can be drawn and evaluated.

Testing with imaging is vital to diagnose structural causes of gait disturbances. Imaging modalities are chosen based on the patient's symptoms. Nerve conduction studies may be ordered to further evaluate suspected neurological or musculoskeletal etiologies.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of gait disturbances initially involves diagnosing the underlying cause. A proper diagnosis leads to more accurate treatment plans. These plans can require a multifaceted approach incorporating physiotherapy, medications, and deep brain stimulation.[24] The treatment plans range in complexity based on the severity of the affected patient's symptoms and where the symptoms stem.

Patients with vitamin deficiencies can be educated and prescribed proper supplementation to increase their body's levels. Following up with routine laboratory work is essential in these patients to ensure therapeutic levels of vitamins are reached. Similarly, lifestyle modifications can be employed to ensure that patients are repleting nutritional deficiencies through the foods they consume. Patients with neurologic causes of gait disturbances can be treated with medications to provide symptomatic relief as well as increasing neurotransmitter levels to improve gait. Intensive coordinative training on posture and gait is used in degenerative cerebellar disease.

Most of the improvements in the field of gait disturbances have been made with Parkinson disease with effective medications, deep brain stimulation at the subthalamic nucleus, and allied healthcare gait improvement techniques (external cueing physiotherapy intervention, which uses visual and auditory cues to improve gait, treadmill walking, cognitive training, and home-based exercise programs).[25][26][27]

Patients can benefit from multimodal rehabilitation, gait training, assistive devices, and fall prevention measures. Commonly used exercise interventions such as muscle strength, power, and resistance training, as well as coordination training, can improve routine and maximum gait speed in older individuals.

Differential Diagnosis

The suspicion of gait disturbances demands a broad differential encompassing numerous etiologies. A systematic approach to history-taking, physical examination, and diagnostic evaluation is essential to accurately identify the underlying cause and guide appropriate management strategies. The differential diagnosis for gait disturbances includes the following: [28]

Neurologic: Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus, dementia, delirium, stroke, cerebellar dysfunction, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, ataxia-telangiectasia, spinal muscular atrophy, peroneal neuropathy, microvascular white matter disease [29]

Musculoskeletal: Osteoarthritis, hip dysplasia, spinal stenosis

Metabolic: Diabetes mellitus, encephalopathy, obesity, uremia, electrolyte imbalances, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin E and copper deficiencies

Psychiatric: Substance abuse, depression, anxiety, malingering

Other: Tabes dorsalis, pain, medication adverse effects, toxic exposures, trauma, neoplasia, vascular and autoimmune diseases, inflammatory and paraneoplastic processes [30][31]

Prognosis

The prognosis of gait disturbances varies widely depending on the underlying cause, severity, and individual patient factors. In some cases, timely identification and targeted management of the contributing factors can significantly improve gait function and overall mobility. Metabolic etiologies of gait disturbances have a relatively good prognosis. If the metabolic disorder is addressed, patients mostly recover without lasting symptoms.[32] However, for chronic and progressive neurological conditions such as Parkinson disease or multiple sclerosis, gait disturbances may worsen over time despite treatment efforts.[33][34]

Complications such as falls, injuries, and functional decline can further complicate the prognosis, particularly in older adults or those with comorbidities. Multidisciplinary interventions aimed at optimizing gait function, addressing comorbidities, and improving overall quality of life can positively influence prognosis by minimizing disability and enhancing patient independence. Early intervention and comprehensive, personalized care plans tailored to each patient's needs are essential for optimizing prognosis and mitigating the impact of gait disturbances on long-term outcomes.

Complications

Gait disturbances pose significant complications beyond mere mobility challenges, impacting various aspects of patients' lives. One primary concern is the increased risk of falls, which can result in injuries ranging from minor bruises to severe fractures or head trauma, often leading to hospitalizations and functional decline. Additionally, altered gait patterns can contribute to muscle imbalances, joint strain, and chronic pain, further compromising patients' mobility and quality of life. Psychological ramifications, including anxiety, depression, and fear of falling, are also common among individuals with gait disturbances, exacerbating social isolation and reducing overall well-being. Furthermore, gait disturbances may impede patients' ability to perform activities of daily living independently, leading to loss of autonomy and increased reliance on caregivers or assistive devices. Therefore, comprehensive management strategies addressing both physical and psychosocial aspects are essential to mitigate the complications associated with gait disturbances and optimize patient outcomes.

Consultations

Patients with gait disturbances may require consultations from a multidisciplinary team where interprofessional expertise can converge to address the multifaceted challenges. Given that gait disturbances encompass a spectrum of abnormalities arising from diverse underlying etiologies spanning neurological, musculoskeletal, and systemic conditions, comprehensive assessments and tailored management strategies are necessary to restore mobility and optimize patient outcomes and quality of life.

Based on an individual patient's needs, consultations may include the following:

- Dietician

- Endocrinologist

- Geriatrician

- Neurologist

- Occupational therapist

- Orthopedics surgeon

- Pain management specialists

- Physical therapist

- Psychiatrist

- Rheumatologist

- Social worker

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and prevention strategies for gait disturbances primarily focus on identifying and managing modifiable risk factors that contribute to their development. Regular physical activity, including strength and balance exercises, can help maintain muscle strength and coordination, enabling functional independence, reducing the risk of falls and subsequent gait disturbances, particularly in older adults. Furthermore, optimizing underlying health conditions such as diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, and osteoarthritis through proper management and lifestyle modifications can mitigate their impact on gait function. Environmental modifications, such as removing hazards and installing handrails or grab bars, can also enhance safety and reduce fall-related injuries. Additionally, educating patients and caregivers about fall prevention strategies and encouraging regular vision and hearing screenings can further contribute to the prevention of gait disturbances and their associated complications. Corrective rehabilitation, gait training, and the use of assistive devices should be implemented.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Identifying patients with gait disturbances requires a high index of suspicion. A wide range of specialties and professions contribute to properly diagnosing gait disturbance. Healthcare professionals must possess clinical skills for assessing gait disturbances, including the ability to conduct comprehensive physical examinations, interpret diagnostic tests, and recognize subtle signs of underlying pathology. Medications should be reviewed by the specialists, pharmacists, and nursing staff to ensure there are no interactions between drugs causing a gait disturbance. Patients should engage in open dialogue with their caretakers, noting any specific changes in lifestyle or diet, which may help uncover the etiology of their gait disturbance.

Physicians, advanced care practitioners, physical and occupational therapists, and nurses should be proficient in implementing evidence-based treatment modalities tailored to individual patient needs, such as exercise therapy, medication management, and assistive device prescriptions. The interprofessional team should engage in open, respectful communication with colleagues from diverse disciplines, sharing relevant information, coordinating care plans, and promptly addressing any concerns or discrepancies. This may involve regular team meetings, case conferences, or electronic communication platforms to facilitate collaboration and information sharing. Healthcare professionals are also responsible for staying informed about advances in the field of gait disturbances and engaging in continuing education to maintain competency and improve patient outcomes.

The interprofessional team must communicate openly and transparently with patients and caregivers and advocate for resources and support services to meet patients' needs. This includes identifying and addressing gaps in care, facilitating referrals to specialist services or community resources, and providing support for patients and caregivers to navigate the healthcare system effectively. Collaborative teamwork places the focus on promoting independence, function, and quality of life for patients with gait disturbances.