Continuing Education Activity

Facial nerve palsies are a common and essential presentation specifically to ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeons but also in general medical practice too. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of facial nerve palsies and highlights the role of the healthcare team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures associated with the course of the facial nerve.

- Explain the common physical exam findings associated with facial nerve palsies.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of facial nerve palsies.

- Identify some interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance care for patients with facial nerve palsies and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Facial nerve palsies are a common and significant presentation specifically to ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeons but also in general medical practice. The facial nerve is a fundamental structure both for communication and emotion, and as such, functional impairment can lead to a significant deterioration in the quality of life.[1]

A key element in the initial assessment of a patient presenting with facial weakness is distinguishing between a lower motor neuron (LMN) versus an upper motor neuron (UMN) palsy, as the likely causes and, therefore, treatment for these vary significantly. Applying anatomy to clinical history and examination, a clinician can identify the probable cause of facial nerve palsy and subsequently direct management appropriately.

Etiology

Idiopathic/Bell Palsy (70%)

Most commonly, the cause for facial nerve palsy remains unknown and has the name ‘Bell palsy.' Bell palsy has an incidence of 10 to 40 per 100000.[2] It is a diagnosis of exclusion.

It usually presents as a lower motor neuron lesion with total unilateral palsy. There is thought to be a viral prodromal period, and it can be recurrent in up to 10% of patients; however, the presence of a facial nerve palsy tends to present fully during the first 24 to 48 hours. [3] Damage to the nerve from compression within the bony canal can lead to edema and secondary pressure resulting in ischemia and reduced function. Recovery can take up to 1 year and is incomplete in as much as 13% of patients.

Trauma (10 to 23%)

Fractures involving the petrous part of the temporal bone and facial wounds transecting the branches of the facial nerve can cause facial nerve palsies. It takes an incredibly large force to fracture the temporal bone, and the clinician must look for signs such as hemotympanum, battles sign, and nystagmus. Temporal bone fractures usually occur unilaterally and are classified according to the plane of fracture along the petrous ridge (i.e., longitudinal vs. transverse. [4] Additionally, iatrogenic injury during otological, parotid, and acoustic neuroma surgery can result in traumatic damage to the facial nerve and stretch injury. Clinical history is vital in identifying the likely cause.

Infection

- Viral (4.5 to 7%) - Herpes Zoster infection resulting in facial paralysis due to geniculate ganglionitis (also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS). The virus remains dormant in the geniculate ganglion. The geniculate ganglion also receives innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). Consequently, the active virus can produce a prodromal period of otalgia and vesicular eruptions within the external auditory canal as well as the soft palate (distribution of CN IX). Additionally, up to 40% of patients with RHS develop vertigo due to the involvement of cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve). [5] Outcomes are much worse than with Bell palsy, with just 21% recovering within 12 months.

- Bacterial - Acute otitis media can cause dehiscence within the facial canal resulting in nerve paralysis. Additionally, cholesteatomas and necrotizing otitis externa can cause facial nerve palsies. A rare cause of facial nerve palsy is Lyme disease, with symptoms such as a tick bite, fatigue, headache arthralgia, and erythema migrans occurring between 1 to 2 weeks after tick exposure. Cardiac involvement (myopericarditis) and arthritis can also occur as part of the syndrome. IgM + IgG serology is vital in these patients from an investigative standpoint. Any patient presenting with a history of erythema migrans and foreign travel exposure requires immediate investigation for Lyme disease.

Neoplasia (2.2 to 5%)

A slowly progressing onset of facial palsy should raise the suspicion of malignancy and prompt a full and thorough head and neck examination. Malignancies resulting in facial nerve paralysis include (but are not exclusive to) parotid malignancies, facial and acoustic neuromas, meningioma, and arachnoid cysts. These will all present with varying degrees and manifestations of facial nerve palsy due to the relative location of the tumor.

Facial Nerve Palsy in Children

The causes of facial nerve palsy in children classify as either congenital or acquired. Acquired causes are the same as in adults as described above, and all of the above etiologies can occur in children.

Congenital causes include:

- Traumatic such as high birth weight, forceps delivery, prematurity, or birth by cesarean section.

- Syndromic cases include those with craniofacial abnormalities such as Moebius syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome syringobulbia, and Arnold Chiari malformations.

- Genetic causes such as hereditary myopathies (myasthenia and myotonic dystrophy. The chromosome loci 3q21-22 and 10q21.3-22.1 have been isolated as causes of hereditary forms of facial paralysis.[6]

It is worth noting that surgical decompression of the facial nerve within the labyrinthine segment is not recommended for the pediatric population as research has failed to demonstrate beneficial outcomes, and there is a significant risk of sensorineural hearing loss with the procedure.[7] However, nerve grafts and muscle transfer techniques may still be options for this cohort.

Bilateral Facial Nerve Palsy

Bilateral facial nerve paresis is an uncommon but essential branch of facial nerve palsy, occurring in between 0.3 to 2% of all facial nerve palsies.[8] Bilateral palsy is important as it is much more likely to represent a systemic manifestation of the disease, with under 20% of cases being idiopathic. Lyme disease represents a significant portion of bilateral facial nerve palsies, accounting for around 35% of cases. Other important differential considerations include Guillain-Barre syndrome, diabetes, and sarcoidosis. Neurological causes of a bilateral facial nerve palsy include Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, and pseudobulbar/bulbar palsy.[9]

Epidemiology

While the majority of cases are found to be idiopathic, any clinician needs to rule out a cerebrovascular event or other serious underlying pathology.[10] At present, no clear evidence exists to suggest facial nerve palsies are more likely in any gender or race, and all ages could be affected. However, it is a known fact that facial nerve palsies most commonly affect those between the ages of 15 to 45 years.[11]

Within the spectrum of facial nerve palsies, the most common cause is Bell palsy, representing approximately 70% of all facial nerve paralysis. Trauma represents the next largest component of facial nerve palsies, contributing around 10 to 23% of cases. Viral infection resulting in a facial nerve palsy is responsible for between 4.5 to 7%, and finally, neoplasia constitutes between 2.2 to 5%.[12]

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of paralysis of the facial nerve is dependent on the cause. Due to the facial nerve running through a narrow bony canal within the intratemporal course, any cause of inflammation or growth of the nerve will result in ischaemic changes through compression. The nerve is narrowest at the labyrinthine segment; therefore, compression is most likely to occur at this point. Additionally, any cause of skeletal abnormality or trauma may result in disruption of the relationship between the facial nerve and its bony canal, causing paralysis. Some iatrogenic causes of facial nerve palsy (such as acoustic neuroma surgery) occur due to secondary stretching forces as a result of the surgery.

History and Physical

A history of a patient with a viral prodromal period and facial nerve palsy may indicate Bell palsy or RHS. Asking the patient about the development of vesicular eruptions will help distinguish this further. A good otological history (e.g., otalgia, discharge, hearing loss, feeling of fullness in the ear, tinnitus, dizziness) will help to elicit a potential otitis externa/media. It may also assist in the diagnosis of an acoustic neuroma or cholesteatoma. A neurological history is relevant in the context of a UMN facial nerve palsy to help potentially elucidate the cause.

Testing facial movements will help distinguish between an upper (the forehead will be spared) and lower (entire facial movements are compromised) motor neuronal lesion. The degree of facial nerve paralysis is evaluated using the House-Brackman grading system.[13]

Grade Definition

- I Normal symmetrical function throughout

- II Slight weakness on close inspection + slight asymmetry of smile

- III Obvious non-disfiguring weakness, complete eye closure

- IV Obvious disfiguring weakness, cannot lift the brow, incomplete eye closure, severe synkinesis

- V Barely perceptible motion, incomplete eye closure, slight movement of corner of mouth, absent synkinesis

- VI No movement, atonic

Importantly, the difference between grades 3 and 4 is eye closure.

Additional tests used to assess the lesion of the facial nerve clinically are as follows:

- Blink test (corneal reflex) – when tapping on the patient’s glabella, a suspension in blinking will occur on the affected side (the ophthalmic division of trigeminal nerve controls afferent limb, the efferent limb is the temporal and zygomatic branch of the facial nerve)

- Schirmer test (assessing lacrimation of the lacrimal gland) – lacrimation will be decreased by 75% compared to the normal side using a folded strip of blotting paper in the lower conjunctival fornix. It is important to note that a unilateral lesion within the geniculate ganglion can produce bilateral lacrimal deficiencies.

- Stapedial test – This involuntary reaction in response to high-intensity sound stimuli causes contraction of the stapedius muscle and gets mediated by the facial nerve. Testing of the stapedius reflex can be performed using tympanometry.

- Salivary Test – Salivation rate is assessed from a submandibular duct following stimulation with a 6% citric acid solution. If positive, there will be a reduction in salivation by 25% at the affected side and indicate a lesion at or proximal to the root of the chorda tympani.

- Taste test – though using salt sweet, sour, and bitter tastes along the lateral aspects of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. A positive result will indicate a lesion at or proximal to the root of the chorda tympani.

Examine the ear externally to ensure no evidence of otitis externa, otitis media, chronic otitis media, or cholesteatoma. The presence of vesicles may indicate Ramsay-Hunt syndrome.

Examine the parotid for any masses that may reveal a parotid malignancy. Examination of the oral cavity for parapharyngeal swellings and vesicular eruptions is also considered essential.

Examine the eye, initially to establish closure of the lid. If the eye is unable to fully close, then urgent ophthalmology referral and provision of eye protection equipment is advised.

Evaluation

Bloods:

Blood tests such as a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, and a C-reactive protein is necessary for all patients admitted due to an infectious cause of facial palsy.

Varicella-zoster virus antibody titers would appear elevated in RHS.

IgG and IgM would become elevated in Lyme disease.

Special Tests:

An audiogram should be performed semi-urgently to determine the type of any associated hearing loss and the degree.

Electrophysiological tests are suitable for prognosis; however, they are expensive, time-consuming, and has a short time to be useful (less than three weeks after symptom onset)[14]:

- Minimal to maximal stimulation tests - the facial nerve is stimulated with a low current on the affected side and gradually increased until maximal response or patient tolerability. This response then gets compared to the unaffected side with a 4-stage grading system. The test is positive if there is a clinically significant difference between the two sides.

- Electroneurography (ENOG) aims to establish muscle action potential amplitude and is the most accurate at determining the level of palsy. It involves facial nerve stimulation around the level of the stylomastoid foramen and the detection of a motor response near the nasolabial fold. This response then gets compared with the normal side.

- Electromyography (EMG) – determines activity within the facial muscles through the detection of fibrillation potentials that only manifest after around three weeks of denervation.

- Magnetic Stimulation – tests intratemporal and brain stem aspects of facial nerve through transcranial stimulation. The test needs to be performed immediately as Wallerian degeneration of the nerve will alter the result findings. Magnetic stimulation can be beneficial for intratemporal facial nerve injury where axonal integrity remains, as proximal site stimulation with higher than usual stimulus intensities overcome the block at the injury site and allow facial nerve activity to occur.[15]

Imaging:

CT: If necrotizing otitis externa or a complication of middle ear infection is suspected, or there is a history of head trauma or suspicion of malignancy, a CT of the temporal bones is necessary.

MRI scanning is useful for the detection of intratemporal lesions that may be resulting in compression of the facial nerve and particularly useful for imaging the cerebellopontine angle. MRI scans may also identify the enhancement of the facial nerve around the geniculate ganglion.

Treatment / Management

Conservative

- Eyecare is incredibly essential in those with palsies resulting in corneal exposure. Artificial tears, adequate lubricant, and taping the eyes closed at night ensure the prevention of corneal ulceration. Ophthalmology referral is a recommendation.

- Facial massage + exercises promote active rehabilitation and are essential for patients with facial nerve palsy.

Medical

- Bell Palsy – current management supported by a Cochrane review with over 1500 patients suggested that the use of steroids and analgesia will increase recovery of motor function if started within 72 hours of symptom onset. [16] If, within this period, prednisolone 50 mg once a day should be commenced for ten days. If a reducing regime is preferred, 60mg of prednisolone once a day should be given, followed by a daily reduction of 10mg for a total treatment duration of ten days. The introduction of antivirals only showed minimal benefit for bell palsy, and one study concluded that this combination should be reserved for Ramsay Hunt syndrome.[17] Over 70% of patients with Bell palsy will recover motor function completely within six months without any treatment.[10]

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome management includes steroid therapy as described above, analgesia + acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day for between 7 to 10 days to combat the viral infection. With a full complement of treatment, facial nerve function is expected to recover in about 75% of patients.[18] Evidence that antiviral therapy is beneficial in Ramsay Hunt syndrome is still lacking; however, their use is still widely practiced.[19]

- Acute otitis media and mastoiditis related bacterial infection require a complement of intravenous antibiotic therapy (type and duration according to local microbiological guidance).

- Lyme disease management depends on patient age and disease severity. If localized disease in an individual over the age of eight, 200 mg once daily doxycycline for a total of 10 days is recommended. If under the age of eight, a 14-day course of amoxicillin or cefuroxime to avoid potential tooth staining with tetracycline use.[20] For most early and localized cases, treatment usually is curative.

Surgical

- In Bell palsy: an over 90% degeneration on ENoG is associated with poor prognosis, and therefore, surgical decompression of the facial canal should merit consideration. However, this has not shown significantly positive outcomes compared to conventional medical treatment.[21]

- For acute suppurative otitis media + mastoiditis, myringotomy +/- ventilation tube and or cortical mastoidectomy is advised.

- Iatrogenic causes: if a facial nerve palsy is apparent immediately after otological surgery, then a watch and wait policy should be adopted as this can be due to local anesthetic use. After the exclusion of a local anesthetic cause and assuming the surgeon is confident that the facial nerve epineurium is intact, a conservative approach with steroids is an option. Otherwise, an urgent re-exploration, facial decompression +/- nerve grafting must take place. Delayed palsies post-operatively can be due to edema and infection (requiring steroids and antibiotics) but also from over tight packing in open mastoid surgery, which requires removal.

- Temporal bone fracture – if immediate and complete facial nerve paralysis occurs, then specialist nerve decompression is required as immediately as the patient’s condition allows (usually within 2 to 3 weeks). If there is a delayed diagnosis and ENoG degeneration of more than 90%, then surgical exploration is required. Specific assessment of the facial nerve will help to dictate the approach as determining the site of nerve damage.

Types of surgery for facial paralysis

- Facial nerve decompression is an option in cases of virally induced facial nerve palsy and also Bell palsy. A trans-mastoid approach would be best for cases of tympanic or mastoid segments damage to the facial nerve. If the damage extends to the labyrinthine segment, then a middle fossae approach allows appropriate decompression. The trans-labyrinthine method is reserved for cases of intratemporal decompression, where cochleovestibular function is absent.

- Facial nerve repair techniques can subclassify into primary repair and cable grafting. Primary repair offers the highest chance of return of facial nerve function. The aim is to provide a tension-free epineural repair, to avoid traction around the anastomosis and axonal injury.[22] If tension-free repair is not possible, then a cable graft approach is used. Commonly utilized nerves include the medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves as well as the sural nerve and great auricular nerve.[23]

- Nerve grafting options tend to be utilized in intermediate durations of facial paralysis (3 weeks to 2 years) with some studies suggesting the best outcomes if performed within six months of insult. [24] This two-stage procedure involves an initial incision on the functional side of the face, nerve selection for sacrifice depending on desired functional outcome, and coaptation of the sural nerve graft to the donor facial nerve branches with tunneling to the contralateral side of the face. Following a 9 to 12 month waiting period, selected facial nerve branches and the cross nerve grafts undergo secondary neurorraphies.[23]

- Muscle transfer techniques are suitable for those patients with chronic facial nerve palsy (older than two years). Regional muscle transfer most commonly utilizes the temporalis muscle; however, the digastric (marginal mandibular nerve injury) and masseter (smile reanimation) are also options. If using temporalis, it is essential to ensure adequate trigeminal nerve function before proceeding. A 1.5 to 2 cm strip of the temporalis is raised and rotated inferiorly beyond the zygoma to the oral commissure to align with the smile vector.[23]

Transcutaneous Nerve Stimulation Transcutaneous nerve stimulation is an additional new treatment option for those with unilateral facial nerve palsy. The technology uses EMG signals from muscles on the intact side of the face to simultaneously stimulate the corresponding muscles on the side of paresis. The ultimate aim of therapy is to achieve facial symmetry. Early trials have shown positive results in significant domains of facial expression where the affected side is paretic, with some degree of reinnervation.[25]

Differential Diagnosis

The most important factor when considering the differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy is whether the lesion is LMN or UMN.

Due to bilateral cortical innervation of the muscles of the upper face, only LMN lesions will result in complete facial paralysis, although this is not always the case.[10] Consequently, the most clinically useful assessment of UMN vs. LMN facial nerve palsy is raising of the eyebrows which assess frontalis and orbicularis oculi.

Lower motor neuronal lesions are ones such as Bell palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and others further described in this article. Upper motor neuronal lesions are responsible for causing facial nerve palsy include stroke, multiple sclerosis, subdural hemorrhage, and intracranial neoplasia.

Prognosis

Factors suggestive of a poor prognosis when associated with a facial nerve palsy include[26]:

- Complete palsy

- Loss of the stapedial reflex

- No signs of recovery within three weeks

- Age over 50 years

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome

- Poor response to electrophysiological testing

Complications

Complications of facial nerve palsy are numerous and significant. Conservative eye care aims to reduce possible ophthalmic complications associated with a facial nerve palsy that include exposure keratitis and drying of the cornea with potential ulceration.[11]

However, other hyperkinetic complications associated with facial nerve palsy include hemifacial spasm, facial asymmetry, and synkinesis.

- Hemifacial spasm is secondary to axonal degeneration of the facial nerve from paralysis and results in involuntary muscle contractions on one half of the face.[27]

- Facial asymmetry is a significant cause of patient concern and can cause considerable distress through disfigurement.

- Synkinesis is voluntary facial movements that are accompanied by involuntary movements. The most common manifestation of synkinesis is the involuntary movement of the mouth upon eye closure and is known as ocular-oral synkinesis. Another notable manifestation of facial nerve synkinesis is that of gustatory lacrimation, otherwise known as crocodile tear syndrome.[28]

Management for these hyperkinetic complications of facial nerve palsy includes facial muscle therapy and botulinum toxin treatment. Facial muscle therapy seeks to attempt to strengthen the weaker half of the facial musculature to compensate for synkinesis. Botulinum toxin, however, aims to paralyze facial muscles and is used in managing both synkinesis and hemifacial spasm.[29]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with facial nerve palsy have a unique set of challenges with which to cope. Patient education is vital to reduce the risk of complications through self-management regimes. These include issues such as dealing with dry eyes and mouth, how to tape an eye shut as to avoid corneal abrasion/ulceration, dealing with eating and drinking, a new development of facial expression, speech, and language adjustments (and development in children) to name a few. Providing patients with relevant guides and educational material on how to tackle these issues can be hugely beneficial to patient wellbeing and outcome. This information can also be beneficial to the patient's families and friends who may wish to learn further how best to help support an individual with facial nerve palsy. Additionally, some patients with facial nerve palsies find charities and support groups helpful to meet like-minded people to share ideas and collaborate on how best to manage the condition.

Pearls and Other Issues

Anatomy of the Facial Nerve

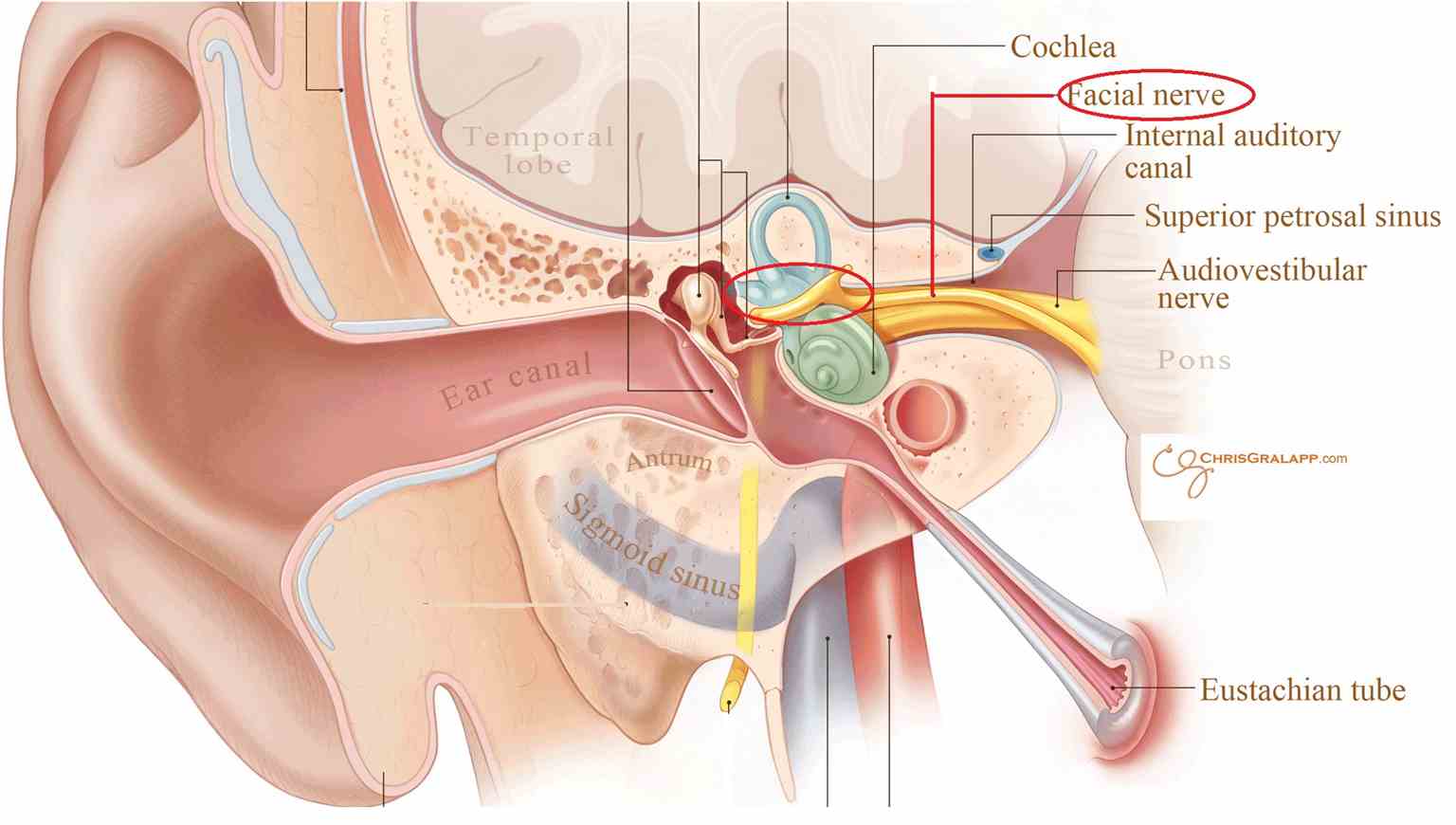

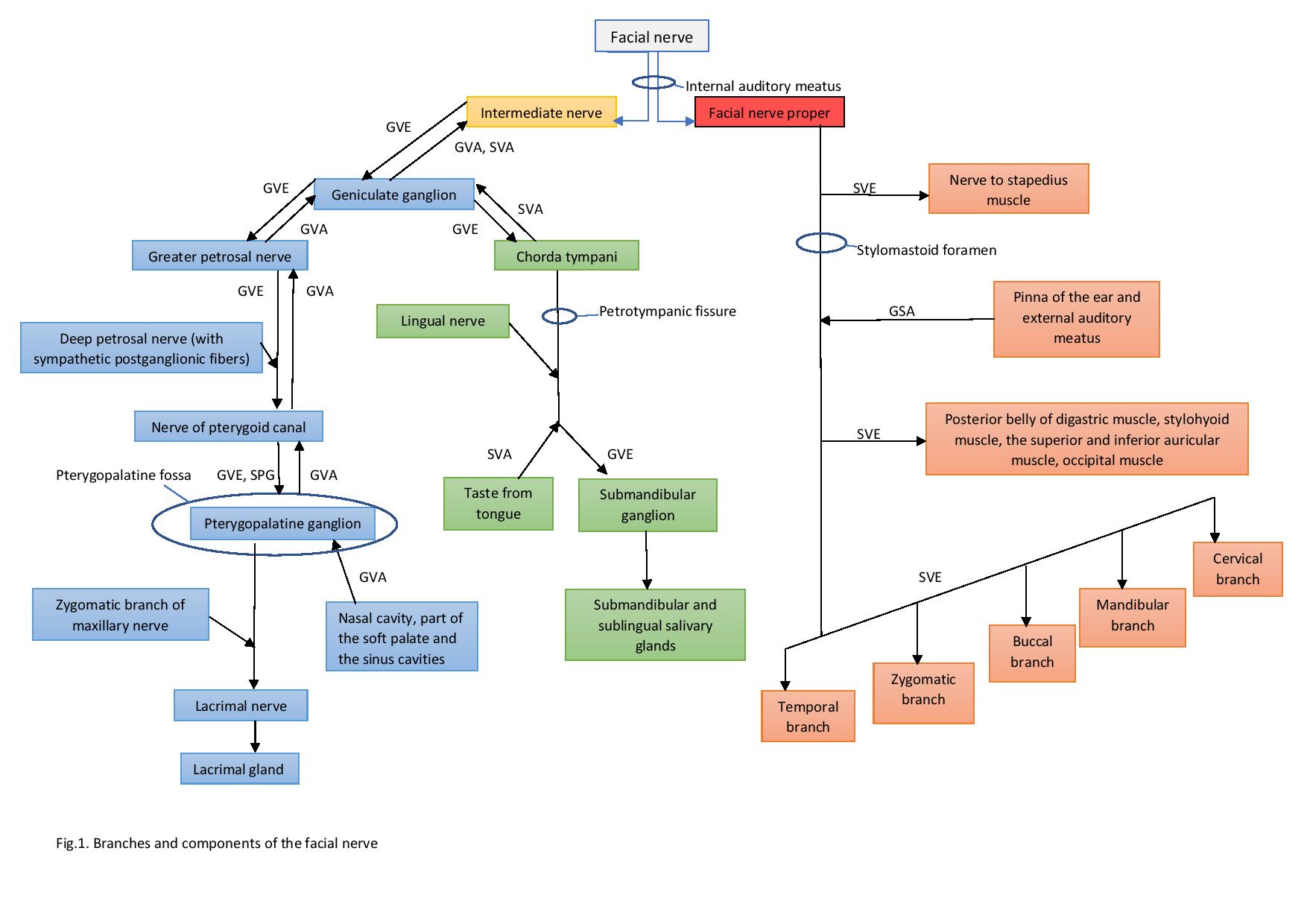

The course of the facial nerve can roughly divide into three portions - origin, intratemporal, and extratemporal.

(a) Origin

The motor nucleus of the facial nerve originates within the lower pons and emerges via the cerebellopontine angle (anterior to the anterior inferior cerebellar artery). Here in its intracranial course, it is joined by the nerves intermedius, which consists of the sensory and autonomic fibers of the facial nerve, which originate from the tractus solitaris and superior salivatory nucleus respectively.

The facial nerve then inserts into the internal acoustic meatus (IAM) to begin its meatal segment. The IAM is in the petrous part of the temporal bone between the posterior cranial fossa and the inner ear.

Within the intracranial and meatal segments, no branches are given off.

At the IAM, the facial nerve runs in the anterosuperior compartment. Important structures within the IAM are:

- Superior vestibular nerve

- Inferior vestibular nerve

- Facial nerve

- Cochlear nerve

- Labyrinthine artery

- Vestibular ganglion

(b) Intratemporal

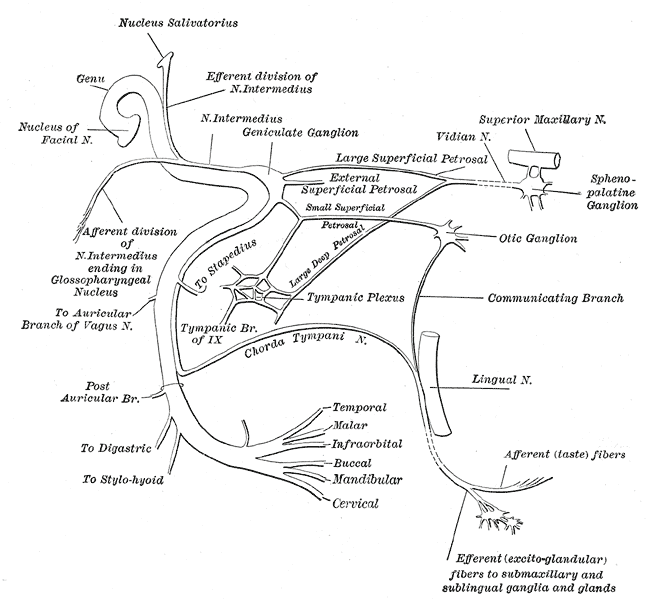

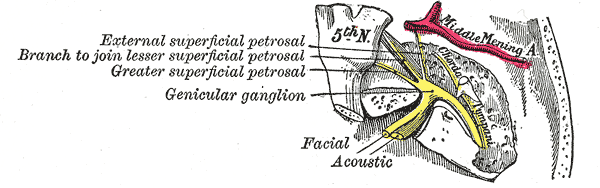

1. Labyrinthine segment - between the IAM+ the geniculate ganglion/first Genu.

This area forms the narrowest portion of the facial nerve (and consequently vulnerable to compromise). At the level of the geniculate ganglion, the facial nerve undergoes the first of two sharp bends (first genu).

At this genu, the greater petrosal nerve branches off from the main trunk. The greater petrosal nerve provides preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the pterygopalatine ganglion (also known as the vidian nerve). The pterygopalatine ganglion provides postganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the lacrimal, nasal and palatine glands. Proximal lesions are associated with impaired lacrimation, hyperacusis, and loss of taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

2. Tympanic segment - between the geniculate ganglion and the second genu.

The facial nerve traverses the bony fallopian canal on the medial aspect of the tympanic cavity before its second sharp bend (genu). Important relations of the facial nerve at this point include:

Anteriorly: Processus cochleariformis (where tensor tympani tendon gets directed to the malleus).

Posteriorly: oval window (inferiorly) and the lateral semi-circular canal (superiorly).

The facial nerve runs between the malleus and incus (running medial to the malleus and lateral to the incus).

3. Mastoid segment - from the second genu to the stylomastoid foramen.

After its second genu, the nerve now runs on the posterior aspect of the tympanic cavity. It runs in front and lateral to the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal and medial to the tympanic annulus.

Both the nerve to stapedius and chorda tympani leave at this segment. The chorda tympani runs anteriorly across the tympanic cavity to provide preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the submandibular ganglion, which then provides parasympathetic innervation to the submandibular and sublingual glands.

To summarise the three important branches of the facial nerve given off before the nerve leaving the stylomastoid foramen are (GCS):

Branch/Segment of facial nerve/Target

Greater petrosal nerve/Labyrinthine/Pterygopalatine Ganglion (palatine, nasal and lacrimal glands)

Chorda Tympani/Mastoid/Submandibular Ganglion (submandibular and sublingual glands)

Stapedius/Mastoid/Stapedius

(c) Extratemporal: The nerve travels inferiorly and laterally around the styloid process. Prior to entering the parotid gland, it gives off branches to the three following muscles:

- Occipitalis

- Stylohyoid

- Posterior belly of digastric

Within the parotid gland, the nerve divides the gland into superficial and deep parts. It lies the most superficial structure traversing the parotid gland. Ordered from superficial to deep, the structures within the parotid gland are:

The facial nerve (superficial) —> Retromandibular vein —> External Carotid Artery —> Auriculotemporal Nerve (deep)

Within the substance of the parotid gland, it divides into two trunks (cervicofacial and temporofacial) and then five main branches which each are responsible for innervation of the muscles of facial expression. The five branches with their target muscle and action are below :

Branch of facial nerve/Primary target muscle/Clinical assessment

Temporal/Frontalis/Raise eyebrows

Zygomatic/Orbicularis oculi/Close eyes

Buccal/Puff cheeks out

Mandibular/Depressor anguli oris/Show bottom teeth

Cervical/Platysma/Clench neck

To summarise, the facial nerve innervates the following muscles:

- Stapedius

- Stylohyoid

- Posterior belly of digastric

- Occipitalis

- Muscles of facial expression

The most important factor when considering the differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy is whether the lesion is lower motor neuron or upper motor neuron.

Due to bilateral cortical innervation of the muscles of the upper face (in particular orbicularis oculi and frontalis), only lower motor neuron lesions will result in complete facial paralysis, although this is not always the case.[10] Consequently, the most clinically useful assessment of UMN vs. LMN facial nerve palsy is raising of the eyebrows which assess the frontalis and orbicularis oculi.

Lower motor neuronal lesions are ones such as Bell palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and others further described in this article. Upper motor neuronal lesions that are responsible for causing facial nerve palsy include stroke, multiple sclerosis, subdural hemorrhage, and intracranial neoplasia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An extensive interprofessional team approach consisting of family physicians, emergency physicians, ENT surgeons, ophthalmologists, radiologists, neurologists, stroke physicians, and maxillofacial surgeons are required to facilitate timely, accurate evaluation and treatment of facial nerve palsies. Paralysis of the facial nerve can present to a variety of healthcare professionals. Therefore it is the responsibility of staff within the primary care setting and also within the emergency department setting to be familiar with the assessment and treatment of this potentially debilitating condition. Following the decision by the initial clinician reviewing the patient (be this a physician and triage nurse) as to whether the palsy is UMN or LMN in nature, then the appropriate next step is further investigations and referral to relevant specialties. Similarly, nursing staff, particularly with experience working on wards caring for patients with head and neck pathologies, should be able to recognize the symptoms and signs of a developing facial palsy. Should a patient develop a facial palsy (particularly in the context of the postoperative period in for example otological surgery or those admitted with a necrotizing otitis externa), then rapid communication to the physician in charge of the patient's care in addition to the rest of the interprofessional team will enhance outcomes.

If the event the treating clinicians chooses pharmaceutical therapy, it would be prudent to enlist the expertise of a pharmacist to verify all dosing, perform medication reconciliation, and counsel the patient in tandem with nursing on proper administration and what side effects may present.

Finally, in the management of patients with facial nerve palsies, an important role is that of both the physiotherapists and speech and language therapists. This intervention is primarily from a rehabilitation perspective, providing patients with facial exercises and therapy to help ultimately restore function in the long term.

A well balanced interprofessional team that provides an integrated and fully holistic approach in patients with facial nerve palsies is essential in achieving superior outcomes. [Level 5]