Continuing Education Activity

Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn (dental lamina cyst) are peculiarly similar lesions that have been confused and interchanged throughout the years. They have a similar clinical appearance, same histology, and natural history of evolution but differ in etiology. This activity describes the evaluation and management of Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn. It highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the appropriate care of affected patients and the counseling of their families.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn.

Describe the presentation of a patient with Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn.

Review the differential diagnosis of Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn.

Identify the treatment for Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn.

Introduction

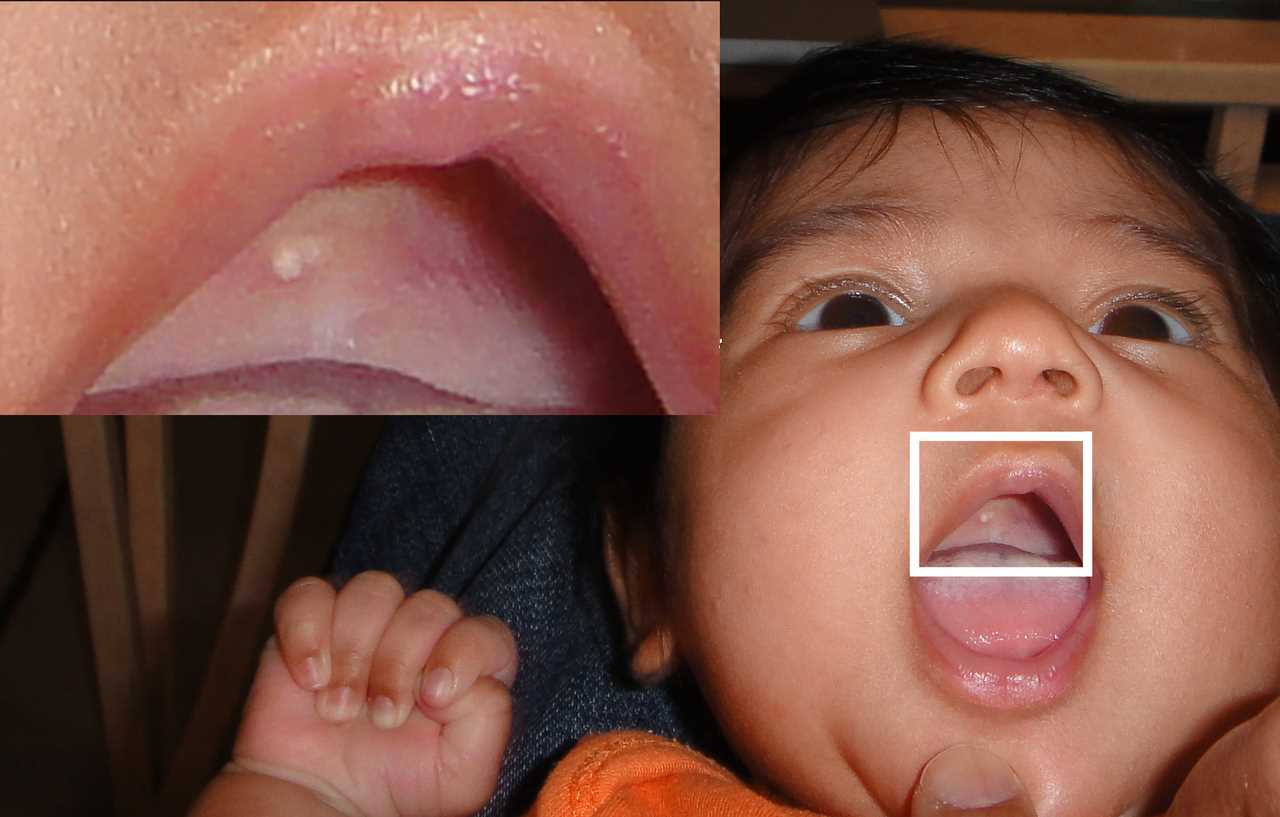

Throughout history, multiple investigators reported a high occurrence of benign palatal mucosal cysts in newborns (see Image. Palatal Cyst of the Newborn). In 1880, a Prague pediatrician, Alois Epstein, first described Epstein disease as the presence of small nodules in the oral cavity of newborns.[1][2][3][4] However, it was not until 1967 that Alfred Fromm undertook the largest study on oral inclusion cysts, where 1367 newborn infants were evaluated. Fromm [5] classified the cysts according to their location and composition as Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and dental lamina cysts and concluded that these lesions were common among infants.

Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cyst of the newborn (dental lamina cyst) are peculiarly similar lesions that have been confused and interchanged throughout the years (see Image. Epstein Pearls). They share more similarities than they show differences: similar clinical appearance, same histology, and natural history of evolution, but differ in etiology.[6]

Currently, palatal cysts is the term used to refer to Epstein’s pearls and Bohn’s nodules, and gingival cysts of the newborn is used to refer to dental lamina cysts.[7][8][9][10][6]

It is not always possible nor required to differentiate between these three entities clinically; they are diagnosed based on their clinical appearance alone, and the course of treatment is the same for all of them. However, health care professionals who work with newborns must be well informed about the clinical aspect of these benign self-resolving lesions to distinguish them from other conditions requiring an invasive approach – congenital epulis of the newborn natal and neonatal teeth.[6]

Etiology

Epstein pearls result from epithelium entrapment during the palate development; Bohn nodules are believed to be remnants of salivary glands; gingival cysts arise from the rests of the dental lamina.[3] However, because of their most common location (junction between the hard and soft palate near the midline), it is hard to verify clinically if a palatal cyst arises from entrapped epithelium after palatal fusion or from developing salivary glands.[6]

Epidemiology

Palatal cysts appear in 65 to 85% of newborns;[6] they may be considered a normal anatomic structure due to their high frequency. Gingival cysts are slightly less prevalent; 25 to 53% of newborns present these lesions.[11]

A study found that palatal and alveolar cysts are more prevalent in full-term (30%) than premature (9%) infants. Palatal and maxillary alveolar cysts risk increases with increasing birth weight, gestational age, and post-natal age.[12] The same study did not find significant differences in gender or race.[12]

Pathophysiology

Near the end of the eight weeks in utero, the palate begins its development. Each maxillary process generates a lateral palatine process within the mouth. These processes are horizontal and shelf-like, growing from the lateral aspect of the mouth toward the midline and downward. Between the tenth and the eleventh week in utero, the lateral palatine processes meet and fuse with each side and the much smaller premaxillary process and the nasal septum. Palatal fusions are normally completed by the end of the fourth month of gestation. In this stage, there is a theory that states that epithelium entrapped between the palatal shelves and the nasal process formed cysts called Epstein pearls.

Another theory expressed that these cysts may come from epithelial remnants that have arisen from the formation of the minor salivary glands of the palate.

Remnants of the dental lamina are believed to remain within the mucosa of the alveolar ridge after tooth development; then they proliferate to form keratinized cysts.[13]

Histopathology

Palatal cysts (Epstein pearls and Bohn nodules) and gingival cysts (dental lamina cysts) are keratin-filled cysts lined by a parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium.[6]

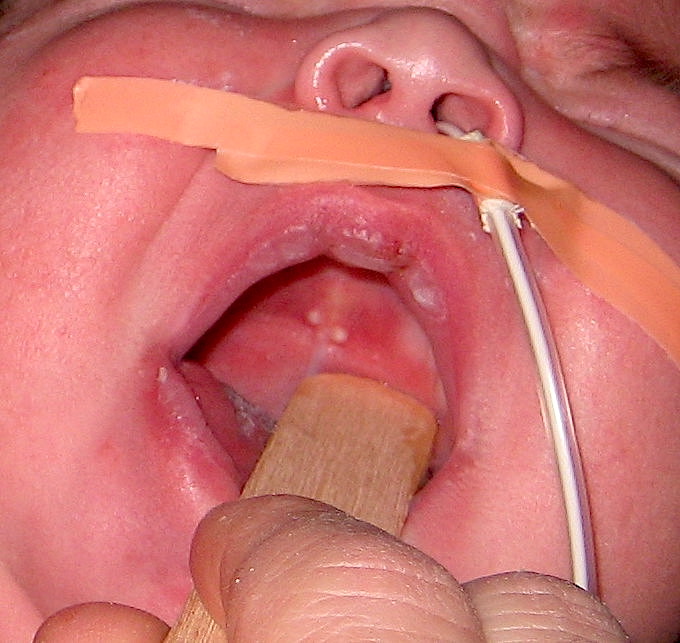

History and Physical

Palatal cysts (Epstein pearls and Bohn nodules) are small painless, white-yellow, firm, non-fluctuant papules of 1 to 3 mm in diameter. They frequently appear in groups of two to six lesions, but they can also present as an isolated cyst.[6] Although not clinically relevant, palatal cysts usually receive a different name according to their location. Epstein pearls are those located along the mid palatine raphe and near the junction of the hard and soft palate, and Bohn nodules are those found on the buccal and lingual surfaces of the alveolar ridges.[6]

Gingival cysts of the newborn appear as small 2 to 3 mm in diameter, isolated or multiple whitish papules on the crest of the alveolar ridge of newborns.[3] They are more commonly found in the maxilla than the mandible and have the same histological appearance as palatal cysts.

Cleft children appear to have palatal cysts in the identical distribution pattern as non-cleft children except for those with a cleft palate which are located at the margins of the palatal shelves instead of the midline.[14]

Epstein pearls resemble the equivalent of milia (white papules produced by retention of sebum and keratin in the hair follicles), which are frequently seen on the faces of neonates.

Evaluation

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are diagnosed based on their clinical features alone.[3] No laboratory or imagining is required as they do not involve bone.

Treatment / Management

No treatment or removal is required as they spontaneously regress within a few weeks or months.[6] They are seldom observed after three months of age. Parental apprehension should be alleviated by reassurance and follow-up appointments.

Differential Diagnosis

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn should be differentiated from natal and neonatal teeth and congenital epulis.

Natal and neonatal teeth are rare and usually located in the lower incisors region.[15] Natal and neonatal teeth tend to be mobile as they lack roots or are too short. These teeth are usually extracted to avoid accidental ingestion.[3] Natal and neonatal teeth can be associated with developmental anomalies and recognized syndromes, including Rubinstein-Taybi, Hallerman-Streiff, Ellis-van Creveld, Pierre-Robin, pachyonychia congenita, short rib-polydactyly type II, steatocystoma multiplex, cyclopia, and Pallister-Hall. Therefore, genetic evaluation is indicated if the patient has any other dysmorphic features.

Congenital epulis is a benign pedunculated soft swelling of 1 mm to several centimeters in diameter, typically located in the anterior maxillary ridge and present at birth. It is occasionally diagnosed in utero.[11] These lesions reach more significant sizes interfering with breathing and feeding, and they are usually excised within the first weeks of life.[11] They do not spontaneously regress or recur after being surgically removed.[16]

Prognosis

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn involute or spontaneously rupture, eliminating their keratin contents into the oral cavity within the first few weeks to months of postnatal life. The lesions are hardly ever seen after three months of age. However, it has been suggested that part of the cystic epithelium may remain inactive even in the adult gingiva.

Palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are believed to resolve spontaneously because their cystic wall fuses with the oral epithelium, consequently discharging the cystic content.[3]

Complications

Palatal and gingival cysts are self-resolving lesions, usually discovered incidentally and are not associated with further complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The clinician should explain that palatal and gingival cysts of the newborn are transient, benign, and asymptomatic lesions that do not interfere with feeding or tooth eruption.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Due to the benign and transient nature of oral inclusion cysts, healthcare professionals sometimes fail to recognize them, differentiate them, and even misdiagnose them.

- Gingival cysts have been mistaken for pseudomembranous candidiasis, leading to the unnecessary use of antifungal medication.[11]

- It is worth noting that Epstein pearls, Bohn nodules, and gingival cysts of the newborn are all managed by reassuring the parents of their benign and self-limiting nature.

- Even tough these three cysts have the same clinical aspect, histopathology, evolution, and treatment they are believed to have different etiology and location in the oral cavity.

- Oral inclusion cysts are identified as Epstein pearls when they are seen on the midpalatine raphe or in the junction between the hard and soft palate, as Bohn nodules when they are found on the vestibular or lingual aspect of the alveolar ridge, and as gingival cysts when they are located on the crest of the alveolar ridges.

- The differential diagnosis should include natal and neo-natal teeth, and congenital epulis of the newborn.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Epstein pearls may be encountered by many professionals including, dentists, medics, midwives, and nurses. The numerous terminology used to refer to oral developmental inclusion cysts of the newborn makes it a very confusing topic. All health care professionals who work with newborn patients should have the appropriate knowledge to identify these lesions and be aware of their benign and transient nature. The key is to reassure the parents that the lesions are harmless and will disappear with time.