Continuing Education Activity

Medial epicondylitis, commonly known as golfer’s elbow, is an overuse injury that occurs from tendinosis of the medial elbow at the origin of the flexor-pronator muscle group. A corticosteroid injection may be indicated when first-line therapies such as activity modification, bracing, analgesics, and physical therapy have failed. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of medial epicondylitis via corticosteroid injection and highlights the interprofessional team's role in coordinating appropriate care of this condition.

Objectives:

Review elbow anatomy at the medial epicondyle.

Outline the presentation and common physical exam findings of a patient with medial epicondylitis and indications for a medial epicondyle injection.

Summarize the procedure details for a medial epicondyle injection.

Describe the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interprofessional team to enhance care coordination for patients receiving medial epicondyle injections.

Introduction

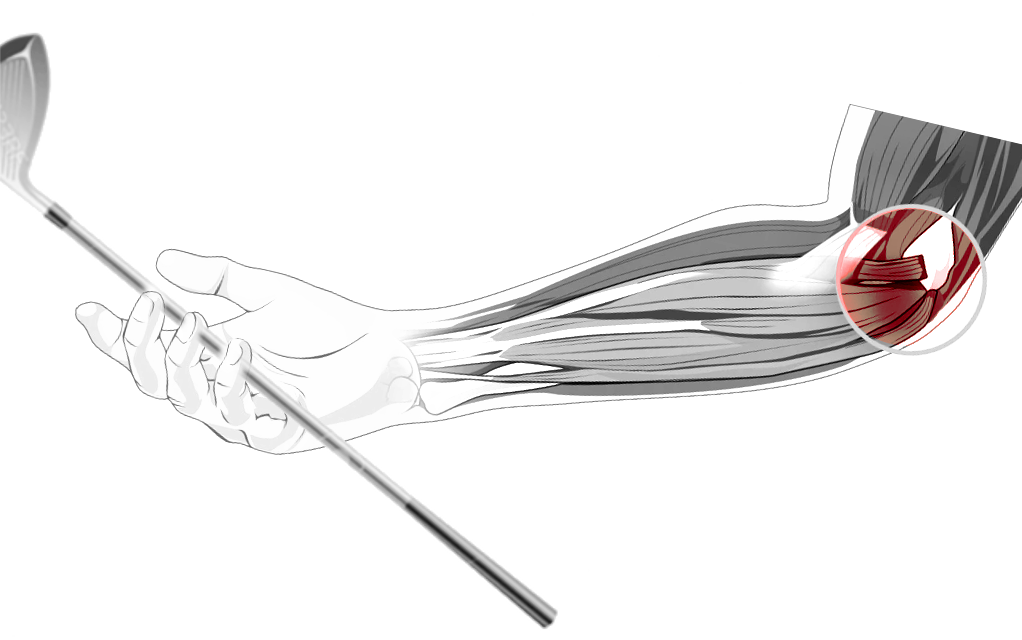

Tendinosis is a frequent cause of elbow pain both in athletes and the general population and is a result of overuse. Medial epicondylitis, commonly known as golfer’s elbow or little leaguer's elbow, represents tendinosis of the medial elbow at the origin of the flexor-pronator muscle group (see Images. Golfer's Elbow, Medial Elbow Anatomy). The tendons most commonly involved in medial epicondylitis include the pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis.

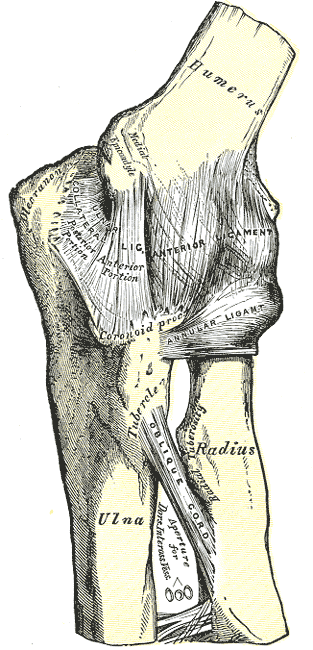

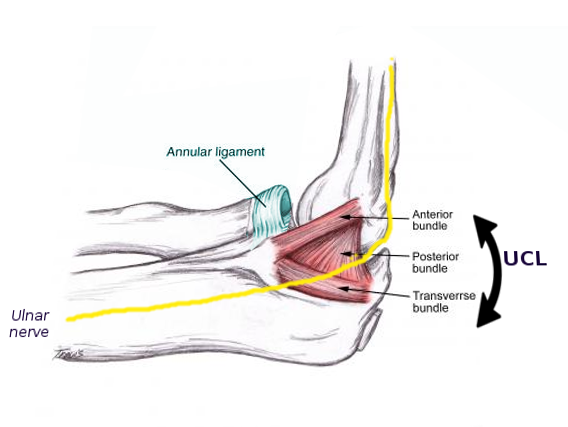

The medial epicondyle is on the distal humerus outside of the elbow joint capsule. It serves as the origin of the ulnar collateral ligament, pronator teres, and the common flexor tendon. The common flexor tendon includes the tendons of the flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum superficialis, and the palmaris longus. It provides stability against both valgus and flexion forces.[1] The ulnar collateral ligament is the primary restraint to valgus instability and is composed of anterior, posterior, and transverse bundles. The ulnar nerve runs posteriorly to the medial epicondyle in the ulnar groove and within the cubital tunnel.[2] See Image. Left Elbow Joint, Anterior and Internal Ligaments.

Etiology

Overuse, specifically repetitive forearm pronation and wrist flexion, results in degenerative changes of the flexor and pronator tendons at their origin on the medial epicondyle. While uncommon, trauma or sudden eccentric contraction of the wrist flexors can result in an acute presentation of medial epicondylitis.[2]

Epidemiology

Research has found the prevalence of medial epicondylitis in working-aged adults to be between 0.4 to 0.6%.[3][4] A study examining medial epicondylitis in the United States military population reported an incidence rate of 0.81 per 1000 person-years.[5] While it may occur in all age groups, it is most prevalent in the fourth and fifth decades of life and most frequently involves the dominant arm. It affects men and women equally. Medial epicondylitis is less prevalent than lateral epicondylitis and represents less than 20% of all epicondylitis diagnoses.[6] Occupations requiring repetitive upper extremity movements, especially repetitive bending and straightening of the elbow, are associated with an increased risk of medial epicondylitis. Sports that require repetitive valgus stress and flexion at the elbow, such as golf, baseball, and bowling, increase the risk of the development of medial epicondylitis.[4]

Pathophysiology

Epicondylitis is an inaccurate term, as this condition does not represent acute inflammation of the bone. Instead, it is chronic tendinopathy of the flexor-pronator mass at its origin on the medial epicondyle. The condition occurs from recurrent microtrauma secondary to repetitive wrist flexion and pronation or repetitive valgus stress and flexion at the elbow. The flexor carpi radialis and pronator teres are the tendons most commonly involved.[6]

Histopathology

Histopathology reveals angiofibroblastic proliferation or disorganization of the collagen matrix with the development of neovessels.[2] Partial or full-thickness tears can occur as a part of the degenerative process.

History and Physical

Medial epicondylitis presents with a gradual onset of pain along the medial elbow that is worse with activity. Symptoms are often mild and intermittent but can be severe, resulting in significant pain and disability. The examination will reveal tenderness along the medial epicondyle and proximal pronator, and flexor tendons. Patients will have pain with resisted wrist flexion and pronation and passive terminal wrist extension. These provocative maneuvers should be performed with the elbow fully extended. In more chronic cases, patients may develop a loss of range of motion with wrist extension. There may be a decrease in grip strength.[6]

In cases of isolated medial epicondylitis, the ulnar collateral ligament and ulnar nerve should not be tender. A valgus stress test to assess the ulnar collateral ligament should be without instability or worsened pain. Ulnar neuritis is assessable by cubital tunnel compression testing and Tinel sign. A careful neurological examination, including 2-point discrimination testing of the fifth digit, is also necessary to assess the ulnar nerve. There is a high association of ulnar neuropathy with medial epicondylitis, occurring concomitantly in 60% of cases.[7]

Evaluation

Medial epicondylitis is a clinical diagnosis and does not require imaging. X-rays may be useful to evaluate recalcitrant cases and to rule out other pathology. MRI and ultrasound can visualize tendinosis but are not a requirement for diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

The initial management of epicondylitis is conservative. Non-operative treatment is successful in over 95% of patients. When treated with observation alone, symptoms persist between six months and two years.[8][9] First-line therapies include rest, ice, analgesics, bracing, and physical therapy. Relative rest and activity modification are key components to resolution and are required in both athletes and the general population for at least six weeks.

During the early stages, when acute inflammation may be present, ice, compression, and elevation may provide benefits. As the condition evolves into chronic tendinosis, these therapies are less likely to be effective. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a common choice for pain relief despite limited evidence on their effectiveness. A Cochrane review demonstrated low-quality evidence for short-term pain relief with topical NSAIDs, while results for oral NSAIDs have been inconclusive.[10]

Bracing typically employs a counterforce strap applied just distal to the elbow joint to minimize the strain applied on the tendon origin at the medial epicondyle. Patients treated with a counterforce brace show improvement in pain and function compared to physical therapy at six weeks, but no difference after 26 weeks. Volar wrist splints are an option to immobilize the wrist and limit flexor activity. While wrist splints may result in a reduction in pain, they should be reserved for severe cases as they may result in a longer duration of symptoms.[11]

Physical therapy includes rehabilitation programs aimed at strengthening and flexibility. It also provides modalities to include soft tissue mobilization therapies. When used in isolation or as adjunctive therapy, eccentric exercises improve function and grip strength in addition to decreasing the pain.[12]

Topical glyceryl trinitrate patches may stimulate collagen synthesis and play a role in healing tendons. When used along with physical therapy, patients demonstrated improvement in both pain and function, with 81% reporting no symptoms at six months.[13]

A medial epicondyle corticosteroid injection merits consideration in patients with symptoms refractory to other conservative measures or for those presenting with severe symptoms. Corticosteroid injections result in improved pain in the short term (less than 12 weeks).[14]

Autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections may result in improvements in the intermediate-term (12 to 26 weeks) compared to corticosteroids.[15] However, low-quality studies and conflicting results prevent routine recommendations for PRP or autologous blood injections.[16]

Both prolotherapy and botulinum toxin A injections result in reductions in pain compared to placebo but are not more effective than corticosteroid injections.[14]

Surgical intervention is rarely necessary but is a consideration in cases with severe pain or marked dysfunction that is refractory to conservative treatments after six months or in cases persisting for longer than 12 months.

Differential Diagnosis

Medial epicondylitis requires differentiation from other causes of pain along the medial aspect of the elbow. This includes ulnar nerve entrapment, ulnar nerve subluxation, ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency, osteoarthritis, little league elbow, osteochondritis dissecans, and posteromedial elbow impingement.[17]

Treatment Planning

Indications for Medial Epicondyle Injection

Corticosteroids are the most common type of injection used for medial epicondylitis and are typically reserved for cases refractory to initial non-operative treatments after 6 to 12 weeks. Injections may also be used earlier in the course of the disease if symptoms are severe.

Contraindications

Contraindications to a medial epicondyle injection include cellulitis or other infection overlying or around the area, allergies to corticosteroid or anesthetic agents, local malignancy, skin breakdown, or fracture at the site of injection. In patients with diabetes mellitus, poorly controlled diabetes with hyperglycemia is an additional contraindication. There is no threshold for the number of injections that can be received; however, multiple injections are not a recommended approach, and instead, injections are usually limited to one.

Equipment

- 5 mL syringe

- 25 gauge, 1-inch needle

- 2 mL of anesthetic agent

- 1 mL corticosteroid (methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone are common agents used. The provider may choose his or her preferred corticosteroid as there is no data to support one steroid type or dose.)[14]

- Gloves

- Chlorhexidine, alcohol pads, or other skin cleaning solution

- Topical anesthetic spray (optional)

Personnel

Physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners trained in this procedure can perform the injection. A medical assistant, nurse, athletic trainer, or other assistants may be used to prep the patient.

Preparation

The provider will discuss the risks and benefits of the procedure and obtain written informed consent. A time-out to identify the patient, procedure, and site of the procedure should take place before the procedure.

Technique

The patient is placed in the supine position with the arm abducted and supinated. The point of maximal tenderness is palpated over the medial epicondyle and may get marked by indenting the skin with the tip of a pen or the capped needle. The injection site is then cleaned with chlorhexidine. An assistant may spray the area with topical anesthetic spray if desired. Using an aseptic technique, the needle is inserted directly down to the level of bone then withdrawn 1 to 2 mm before slowly injecting the anesthetic and corticosteroid solution. Ultrasound guidance has not demonstrated improved clinical outcomes compared to blinded techniques.[18][19]

A peppering technique that involves needle insertion with multiple small injections performed by retracting and repositioning without withdrawing the needle from the skin is also an option. Multiple passes are made until the clinician no longer feels crepitus while passing the needle. This minor fenestration of the tendon causes bleeding and inflammation, which may stimulate a healing response.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory properties and can modify the body's immune response. The most feared complication of corticosteroid injections is an acute infection due to immunosuppression. With proper adherence to aseptic technique, this complication is exceedingly rare.

Common complications of the procedure include skin atrophy or skin hypopigmentation at the site of the procedure. Some patients may have a paradoxical increase in pain for the firth 24 hours after the injection. Increased pain that lasts for several days after the procedure is a rare complication known as a "steroid flare."

In patients with diabetes mellitus, it is imperative to note blood glucose levels before and after corticosteroid injection to prevent severe hyperglycemic episodes.

Prognosis

There is a paucity of data for outcomes of injections with medial epicondylitis, and much of the data used to guide treatment has been extrapolated from studies for lateral epicondylitis. Despite a lack of inflammation, corticosteroids are likely effective by providing relief of pain of neurogenic origin. Corticosteroids are effective in improving short-term pain relief. However, there is a high recurrence of pain and lack of benefit demonstrated at one year compared to observation and physical therapy. Therefore, corticosteroid injections should only be performed concurrently with other non-operative therapies.[20] Comparisons of a single injection of corticosteroid or a peppered injection of corticosteroid have shown more favorable results with the peppered technique.[21][22]

Complications

- Transient vasovagal reaction

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Acute worsening of pain

- Skin and fat atrophy

- Ulnar nerve damage

- Worsening of degeneration of the tendon

- Worsened pain and function after three months[23]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should receive advice regarding relative rest following a medial epicondyle corticosteroid injection. Patients should understand the possibility of a steroid flare that can acutely worsen the pain; this is treatable with ice, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs.

Following an injection, patients should continue with activity modifications and other therapies until the pain subsides. A session on proper mechanics should take place before returning to work or sports. A slow functional progression of sport-specific exercises is required for a successful return to play. Typically, activity modifications and treatment are necessary for a total period of 6 to 12-weeks.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Medial epicondylitis is a chronic condition that can negatively impact function and cause significant pain. Initial treatment is conservative and requires multiple healthcare team members, including the clinical provider, nurses, medical assistants, athletic trainers, pharmacists, and physical therapists, to provide education, bracing, medications, and rehabilitation.

To improve healthcare outcomes, it is essential to have a functioning, cohesive interprofessional team, especially if a medial epicondyle injection is planned. The clinical providers should communicate the treatment plan with the specialty nurses, pharmacists, and physical therapists to achieve this goal. The pharmacists' role in these cases involves a thorough evaluation of the patient's medication profile and previous treatments to identify any possible interactions or adverse reactions. By communicating these findings with the medical team, the pharmacist can help decrease adverse reactions for these patients. The specialty nurse plays a crucial role in educating the patient in regards to post-procedure restrictions and monitoring, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus. Identifying patients most at risk for complications, the nurse can help focus the healthcare team's resources where they would be most effective. The physical therapist will need to alter the treatment plan once a medical epicondyle corticosteroid injection is given. The medical provider needs to communicate this with the physical therapist to ensure appropriate therapy is delivered. [Level 5]