Continuing Education Activity

In its simplest form, the endotracheal tube is a tube constructed of polyvinyl chloride that is placed between the vocal cords through the trachea. It provides oxygen and inhaled gases to the lungs and protects them from contamination, such as gastric contents or blood. The advancement of the endotracheal tube has closely followed advancements in anesthesia and surgery. Modifications have been made to minimize aspiration, isolate a lung, administer medications, and prevent airway fires. Despite these advances, more research to optimize its use is necessary. For example, endotracheal tubes are implicated in the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia, which remains a major concern. This activity describes the indications, contraindications, and techniques involved in endotracheal tube placement and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

Identify indications and contraindications for endotracheal tube placement.

Describe potential complications of endotracheal tube placement.

Outline the anatomy that is relevant to the placement of an endotracheal tube.

Summarize a structured, interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to and appropriate surveillance of patients undergoing endotracheal tube placement.

Introduction

The endotracheal tube (ETT) was first reliably used in the early 1900s.[1] In its simplest form, it is a tube constructed of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) that is placed between the vocal cords through the trachea to provide oxygen and inhaled gases to the lungs. It also serves to protect the lungs from contamination, such as gastric contents and blood. The advancement of the endotracheal tube has closely followed advancements in anesthesia and surgery.[2] Modifications have been made to minimize aspiration, isolate a lung, administer medications, and prevent airway fires. Despite advances in the endotracheal tube, more research to optimize its use is necessary. For example, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a major concern, and the ETT itself is felt to be a primary agent for the development of VAP.[2]

Pediatric ETT’s are sized by age with options across the spectrum from premature infants to adult-size teenage children. Historically, pediatric endotracheal tubes were uncuffed for fear that the pressure from the cuff would damage the trachea via pressure necrosis, as the airway just below the vocal cords (cricoid cartilage) is the most narrow part in children. In adults, the narrowest portion of the airway is the vocal cords. Except for neonatal patients, this practice has largely been discontinued in favor of cuffed pediatric ETT’s.[3] A few well-established criteria are available to aid in ETT size selection.

Anatomy and Physiology

The Tube

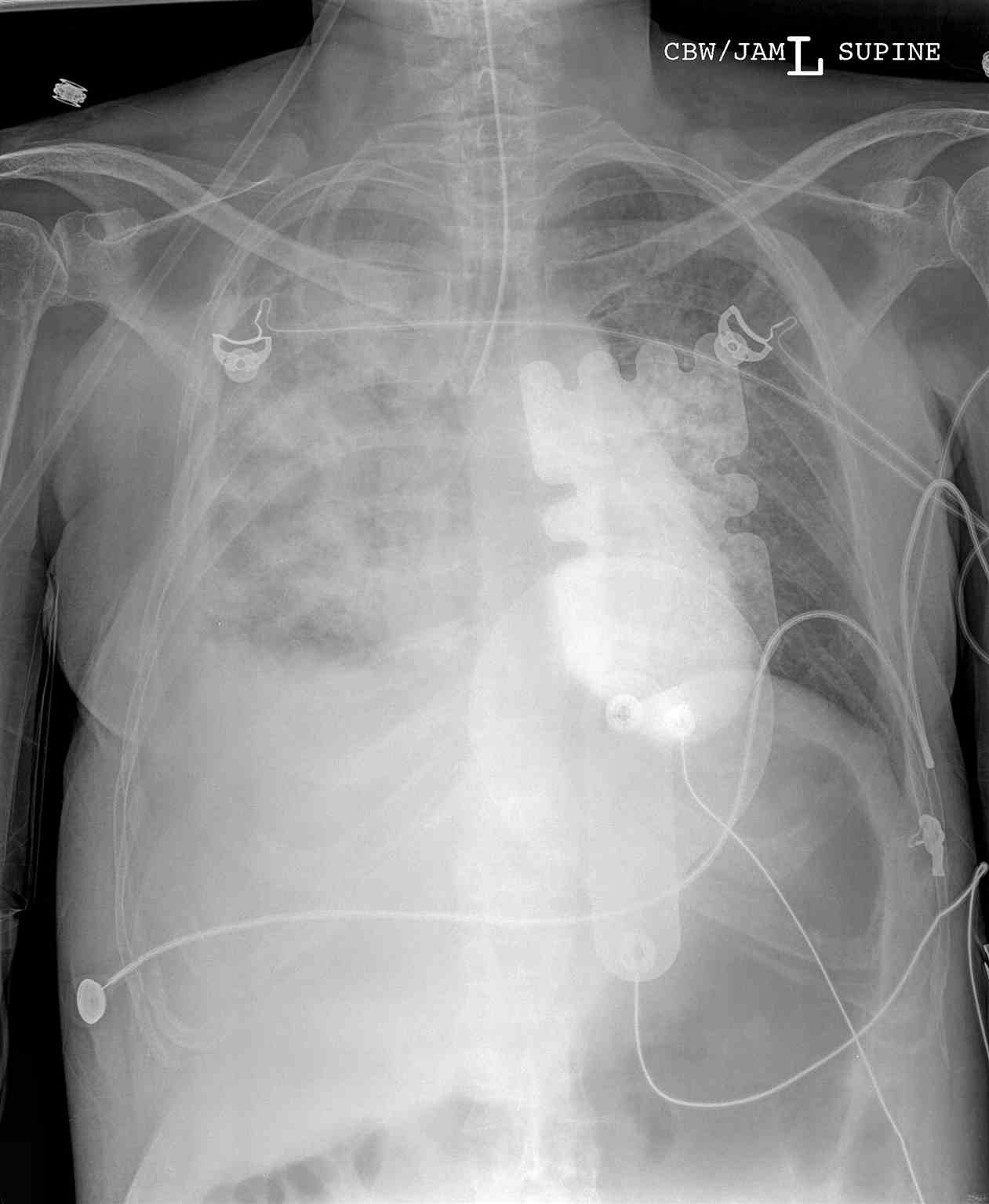

The endotracheal tube has a length and diameter. The endotracheal tube size ("give me a 6.0 tube") refers to its internal diameter in millimeters (mm). The ETT will typically list both the inner and outer diameter of the tube (for example, a 6.0 endotracheal tube will list both the internal diameter, ID 6.0, and outer diameter, OD 8.8). The narrower the tube, the greater the resistance to gas flow. Medical providers, thus, should select the largest tube that is appropriate for the patient; this is critically important to the spontaneously breathing patient who will have to work harder to overcome the increased resistance (a size 4 ETT has 16 more times resistance to gas flow than a size 8 ETT). The ETT is measured from the distal end of the tube and is typically marked in 2 cm increments. After successfully intubating the patient, the depth of the endotracheal tube ending at the teeth or lips should be noted. This depth provides a baseline measurement to ensure the tube has not traveled out of the trachea or deeper into the trachea with patient movement or transport. PVC is not radiopaque, and thus, a radiopaque linear material is included throughout the length of the tube to make it easier to visualize the placement on X-ray. Ideally, the distal tip of the ETT is 4 cm (+/- 2 cm) above the carina on chest X-rays in adults.[4] Should you desire to perform bronchoscopy on an adult patient with a standard bronchoscope (diameter 5.7 mm with a 2 mm suction channel), the patient typically needs to be intubated with at least 7.5-8.0 size ETT; ETTs larger than 8.0 are available and used for bronchoscopy.[5] The typical depth of the endotracheal tube is 23 cm for men and 21 cm for women, measured at the central incisors. The average size of the tube for an adult male is 8.0, and an adult female is 7.0, though this is somewhat an institution dependent practice. Pediatric tubes are sized using the equation: size = ((age/4) +4) for uncuffed ETTs, with cuffed tubes being one-half size smaller.[6] Typically, a pediatric ETT is taped at a depth of 3 times the tube size in a child (i.e., a 4.0 ETT commonly gets taped at around 12 cm depth).

The Cuff

A cuff is an inflatable balloon at the distal end of the ETT. Pediatric ETTs are produced with and without cuffs. The inflated cuff produces a seal against the tracheal wall; this prevents gastric contents from entering the trachea and facilitates the execution of positive pressure ventilation. The cuff inflates by attaching an appropriate size syringe (10 to 20 ml for adult ETT) to the pilot balloon. The syringe provides air under pressure and inflates both the pilot balloon and the cuff. Once the cuff inflates, the syringe must be removed, or the air in the cuff may redistribute back to the syringe and deflate the cuff. Palpating the firmness of the pilot balloon is a good estimation of the pressure in the cuff. Cuff manometers are available but not common in clinical use. The ideal cuff pressure should be 20 cm H2O or less. If the pilot balloon does not hold air, it must be assumed the cuff of the ETT has been damaged and is non-functional. Some ETTs have a low volume, high-pressure cuff, but it is more common to find high volume, low-pressure cuffs on ETTs in current medical practice.

The Bevel

The ETT has an angle or slant known as a bevel to facilitate placement through the vocal cords and to provide improved visualization ahead of the tip. As the endotracheal tube approaches the cords, the left-facing bevel provides an optimal view.

The Murphy's Eye

ETTs have a built-in safety mechanism at the distal tip known as Murphy's eye, which is another opening in the tube positioned in the distal lateral wall. If the distal end of the ETT should become obstructed by the wall of the trachea or by touching the carina, gas flow can still occur via Murphy's eye. This prevents complete obstruction of the tube.

The Connector

ETT connectors attach the ETT to the mechanical ventilator tubing or an Ambu bag. For adult and pediatric ETTs, it is customary to use the universal 15 mm connector.

Indications

The main indication for the use of an endotracheal tube is to secure a definitive airway. A definitive airway is the placement of an ETT in the trachea with an inflated cuff below the vocal cords. The main reasons to secure a definitive airway are an inability to maintain airway patency, inability to protect the airway against aspiration, failure to ventilate, failure to oxygenate, and anticipation of a deteriorating course leading to respiratory failure.

Contraindications

The primary (relative) contraindications to the placement of an ETT in the oropharynx are severe airway trauma or obstruction that does not allow safe placement of the tube, severe cervical spine injury which requires complete immobilization, and those patients with Mallampati III/IV classification suggesting potentially difficult airway management.

The main contraindications to avoid placing an ETT with the nasotracheal approach include facial trauma, head trauma concerning for basilar skull fracture, active epistaxis, expanding neck hematoma, oropharyngeal trauma, and apneic patients.[7]

Equipment

Equipment necessary to optimize the use and function of the ETT:

- Stylet

- Syringe for cuff/pilot balloon

- Universal 15 mm connector

- End-tidal CO2 device

Personnel

In the emergency department, it is common to have an RN available to push drugs (if needed). The RN can function as a second person and can call for help if needed for an unanticipated difficult airway. Some hospitals commonly have an RT help with taping of the ETT and ventilation once a patient is intubated.

Preparation

Select an appropriate size endotracheal tube and remove it from the package. Lubricate the distal end and balloon (if not emergency placement). Attach a proper size syringe (10 to 20 cc) filled with air to the pilot balloon and test the balloon by blowing it up and then deflating it. Place a stylet into the ETT and bend it to an appropriate shape. Place the tube with the stylet and attached syringe back in the package, ready for use. Repeat the same procedure with a tube one size smaller in case of difficult intubation. Set aside an end-tidal CO2 detector.

Complications

Several mechanical complications can occur with the ETT, resulting in a loss of function. A defective balloon will result in a loss of ability to protect the airway from aspiration and may make mechanical ventilation difficult. The loss of the universal 15 mm connector (either missing or defective) essentially makes the ETT nonfunctional, as the mechanical ventilator or bag valve mask cannot interface with it. Some complications from the physical placement of the tube include bleeding, infection, perforation of the oropharynx (especially with the use of a rigid stylet), hoarseness (vocal cord injury), damage to teeth/lips, or esophageal placement.

ETTs are usually removed after a procedure or improvement of an acute illness. ETTs cannot be used indefinitely and should be removed within 14 days. Tracheostomy may be needed.

Clinical Significance

Intubation, or placement of an endotracheal tube, is an important life-saving skill. All clinicians who work in emergency rooms, operating rooms, peri-operative areas, and intensive care units (all places with intubated patients) must understand the basics and mechanics of an endotracheal tube. This knowledge is necessary for appropriate ventilator settings and the management of intensive care-level patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team is necessary to make sure that an ETT is placed appropriately, especially in the emergency department setting. As there is no definitive method to ensure appropriate ETT placement, an interprofessional team working together to confirm several means of tube placement is necessary to ensure optimal patient outcomes. For example, after emergent intubation in the emergency department, a respiratory therapist may ensure a good color change of the end-tidal CO2 detector while also securing the ETT. Simultaneously, nursing staff may auscultate over the lung fields and abdomen to ensure good quality, equal breath sounds in the thoracic cavity with absent breath sounds in the abdomen. The physician will be monitoring the pulse ox while ordering a stat portable chest x-ray to confirm the placement of the tube. It has become more common and standard of care to have a constant waveform monitor for end-tidal CO2 for intubated patients, especially in the OR and ICU. Collaboration, closed-loop communication, and the principles of crisis resource management are necessary for the success of teams working in acute care environments.[8]