Continuing Education Activity

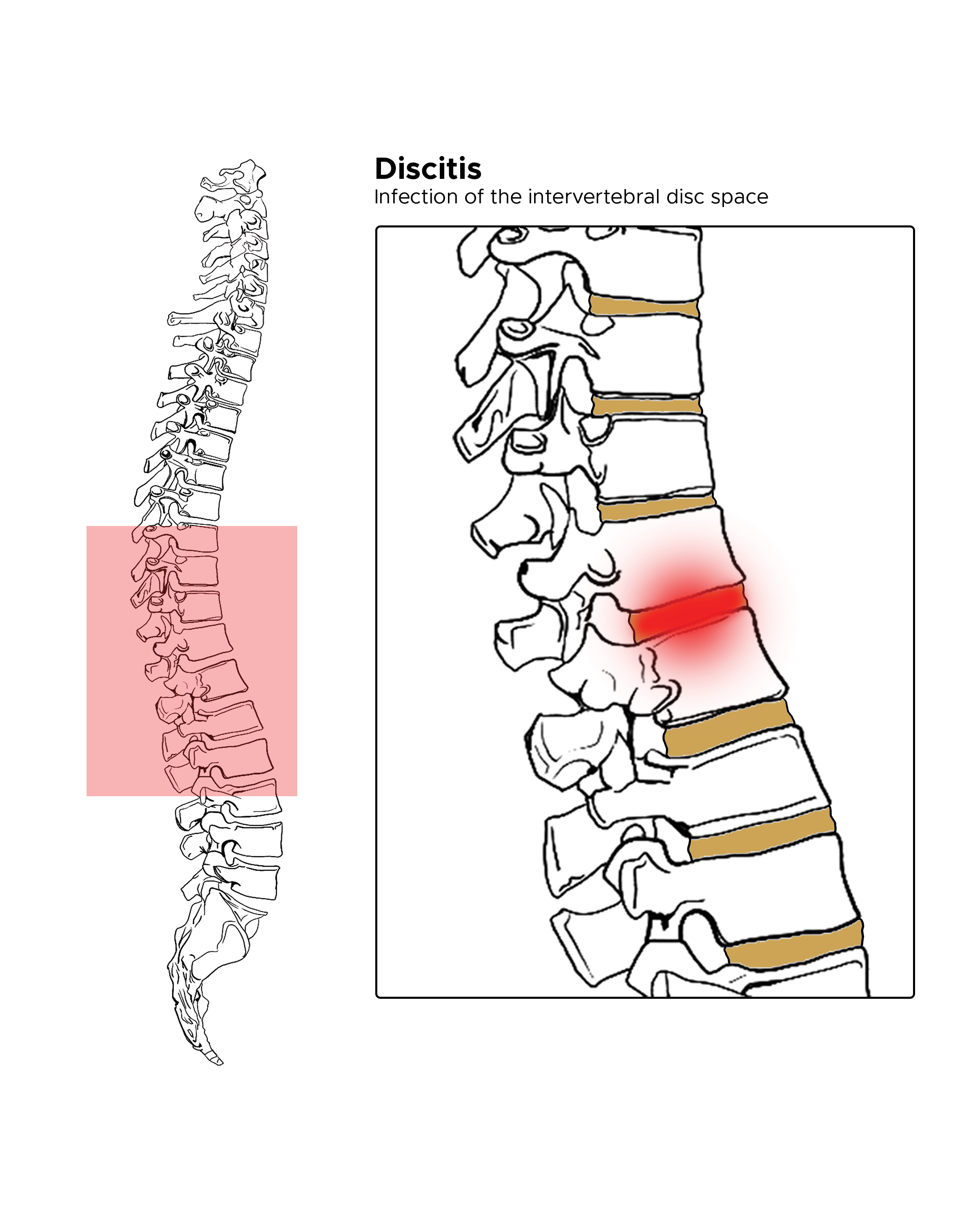

Discitis is a serious but uncommon medical diagnosis. It is an infection of the intervertebral disc space. The role of the intervertebral discs is to separate and cushion the spinal segments from each other. An infection, and thus inflammation of these discs can cause much pain and discomfort. What makes the condition uncommon is also what makes it difficult to treat: the relatively scarce blood supply to these segments. This activity explains when this condition should be considered in a differential diagnosis, articulates how to properly evaluate for this condition, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the causes of discitis.

Outline the presentation of a patient with discitis.

Summarize the treatment options for discitis.

Review the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by discitis.

Introduction

Discitis is a serious but uncommon medical diagnosis. It is an infection of the intervertebral disc space. See Image Discitis. The role of the intervertebral discs is to separate and cushion the spinal segments from each other. An infection, and thus inflammation of these discs can cause much pain and discomfort. What makes the condition uncommon is also what makes it difficult to treat: the relatively scarce blood supply to these segments. Treatment consists of a prolonged antibiotic course, but will usually result in uncomplicated resolution of symptoms; however, delay in treatment or misdiagnosis can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.

Etiology

In the majority of cases, discitis stems from one of three inciting events: direct inoculation, hematogenous spread, or less commonly contiguous spread.[1] Identification of the causative agent is difficult, if not impossible at times.[2] A single organism is usually the cause.[3] When positive cultures are obtained, the most commonly identified organism is Staphylococcus aureus.[2][3] Also implicated, although less frequently, are coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Salmonella spp.[2] Fungi have also been causative agents.[2]

Hematogenous spread of disease, such as systemic infection, or bacteremia, can lead to seeding of the vertebrae first, followed by the disc, causing subsequent infection.[2] Sites of origin include urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and other soft tissue infections. Also, contiguous spread from a local infection such as adjacent osteomyelitis to the vertebrae is another potential etiology, as well as any spinal surgery, diagnostic procedure (i.e., lumbar puncture), or local treatment (i.e., injections to the area).

Spinal arteries supply blood to vertebrae and eventually to the intervertebral discs. In children, the blood vessels extend from the cartilaginous endplates into the nucleus pulposus, whereas in adults these vascular supplies degenerate, and only extend into the annulus fibrosis.[2][4][5] The venous system, on the other hand, forms a plexus in the epidural space.[2] The lumbar spinal region is most commonly involved, followed by the cervical spine and then the thoracic spine.[1][2][3]

Epidemiology

The incidence of discitis in the United States is around 0.4 to 2.4 per 100000 people each year.[3] Overall, the frequency of discitis is more common in pediatric patients than in the adult population, which is thought to be due to the vascular supply of the intervertebral discs, which diminish later in life.[4] However, there is a bimodal distribution of ages, as it again increased in incidence around age 50.[3] It is also more common in males than in females.[3] In children, diskitis is part of a continuum of diseases including discitis, spinal osteomyelitis, and soft-tissue abscesses.[6] In children alone, there is a higher incidence in early childhood, with another peak during adolescence.[4] Over half of the cases occur in patients with predisposing medical conditions, most commonly diabetes mellitus.[1] Other risk factors identified include age, immunocompromised individuals, intravenous drug users, alcoholics, hepatic cirrhosis, malignancy, and renal dysfunction.[4]

History and Physical

As always, history and physical examination are paramount in making an accurate and timely diagnosis. The symptoms will depend on the age of the patient, and early diagnosis can prove to be difficult. Reports exist of delays of up to 6 months in diagnosis.[2] In the pediatric population, reports of back pain, refusal to walk, and even abdominal pain are common presenting complaints.[6] Discitis in children has a more acute onset than in adults. In adults, common presenting complaints include back or neck pain, fever, weight loss, anorexia, and neurologic deficit.[3] Unlike some other causes of back pain, the pain of discitis usually localizes to the disc level without radiation elsewhere. Postoperatively, symptoms typically occur 1 to 16 weeks after surgery.[3]

The physical exam should elicit point tenderness over the disc of involvement, with the lumbar region most commonly affected.[1][3] There may be a limited or painful range of motion; however, lower extremity muscle strength, reflexes, and sensation are usually preserved. A neurologic deficit is uncommon, but it may be present in a smaller percentage of cases.[1]

Evaluation

Early diagnosis tends to be difficult primarily due to the unremarkable nature of the laboratory and initial imaging tests. Significant laboratory findings in discitis included elevations in ESR and CRP.[3] The white blood cell count may be normal. Blood cultures should be obtained to guide antibiotic treatment, although, in a high number of cases, the patient will be culture negative.[7] Plain film radiographs are mostly unhelpful.[7] Radiographic findings usually do not manifest until a few weeks into the disease. Positive findings include the narrowing of disc space and the destruction of adjacent vertebral segments.[2] MRI is the most sensitive and specific test for diagnosis.[2][3][4][7] A biopsy can be used for histologic confirmation and to obtain a culture of the causative organism.

Treatment / Management

Experts do not agree on the specific treatment of discitis. Treatment options range from immediate broad-spectrum antibiotics to awaiting cultures for sensitivity before administering antibiotics, to spinal bracing alone without antibiotics.[3][7][8] Most commonly, the treatment of discitis includes antibiotics and less commonly surgery.

The antibiotic should be specific to the causative agent once known.[2][4] Initially, broad-spectrum antibiotics are suitable until culture results are available and permit the narrowing of the agent. It is important to cover for Staphylococcus species initially. The course of antibiotics ranges from 4 to 6 weeks.[7] Patients should also be immobilized to allow fusion of the vertebral segments in proper anatomical alignment, which is accomplished by bed rest and a brace.[3] Pain control is also an important consideration during treatment. Early detection usually can negate the need for surgical intervention. When needed, surgery usually involves debridement.[9] Indications for surgery include neurologic deficits, spinal deformity, and refractory disease.[1][3]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for discitis including common causes of back pain and less common infectious causes. These include but are not limited to:

- Osteomyelitis

- Spinal tumors

- Spinal epidural abscess

- Spinal fracture

- Muscle or tendon injury

- Disc herniation

- Inflammatory spondyloarthropathies

Prognosis

Overall, reports of mortality from discitis run from 2 to 11%.[3] Children recover better with treatment and have less morbidity than adults.[2][3][10] Most patients are cured with antibiotics alone, or with the addition of surgery. Some patients will experience permanent neurologic disability, which usually results from a delay in diagnosis.[2]

Complications

Complications from discitis include spinal deformity, segmental abnormality, and less commonly neurologic deficits.[2] Neonates suffering from the disease can have significant kyphosis.[6] The course overall in children, however, is generally benign.[10]

Consultations

The consultants usually contacted for the diagnosis and successful treatment of discitis include:

- Radiology

- Infectious disease

- Orthopedic surgery

- Neurosurgery

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of discitis is difficult. Infections can often start elsewhere and spread to the disc space. Preventing and treating infections in other areas of the body would be of importance. Infection prevention is vital in diabetics and the immune-compromised, especially, as the disease is most prevalent in these populations.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Discitis is a serious but uncommon cause of back pain

- It is more common in children than adults, has a male predilection, and targets diabetics, and immune-compromised patients

- Diagnosis is often delayed due to the commonality of back pain and unremarkable lab and imagining tests

- MRI is the gold standard of diagnostic testing

- It is usually bacterial

- Treatment consists of antibiotics, immobilization, and less commonly surgery

- Although complete resolution is the most common outcome, neurology deficits can complicate the disease process

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are few studies on discitis and other infections of the spinal column due to the rarity of the disease and usually delayed diagnosis. Early recognition is ideal and provides patients the best outcome. Healthcare providers including nurse practitioners, emergency department physicians, orthopedic surgeons, and rheumatologists must, therefore, be aware of the broad differential of back pain, and presentations of different age groups, including children and neonates, given the predilection of disease in that age group. Appropriate consultations should be ordered, especially when systems persist without a confirmed diagnosis. Overall management includes all of the above specialists in an interprofessional team approach, along with specialty-trained nursing for pediatric and infectious disease as appropriate, and infectious disease pharmacy specialists. [Level V]