Continuing Education Activity

Direct laryngoscopy allows visualization of the larynx. It is used during general anesthesia, for surgical procedures of the larynx, and during resuscitation. This tool is useful in multiple hospital settings, from the emergency department to the intensive care unit and the operating room. By visualizing the larynx, endotracheal intubation is facilitated. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications, and complications of direct laryngoscopy and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the anatomical structures visualized during direct laryngoscopy.

- Describe the technique of direct laryngoscopy.

- Review the indications of direct laryngoscopy.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination of patients undergoing direct laryngoscopy and improving outcomes.

Introduction

A direct laryngoscopy allows visualization of the larynx. It is used during general anesthesia, surgical procedures around the larynx, and resuscitation. This tool is useful in multiple hospital settings, from the emergency department to the intensive care unit and the operating room. By visualizing the larynx, endotracheal intubation is facilitated. This is an important step for a range of patients who are unable to secure their own airway, including those with altered mental status and those who are undergoing a surgical procedure. When using direct laryngoscopy to secure a patient's airway, the physician must be well acquainted with the anatomy, indications, contraindications, preparation, equipment, proper technique, personnel, and complications of the procedure for successful endotracheal intubation.[1][2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

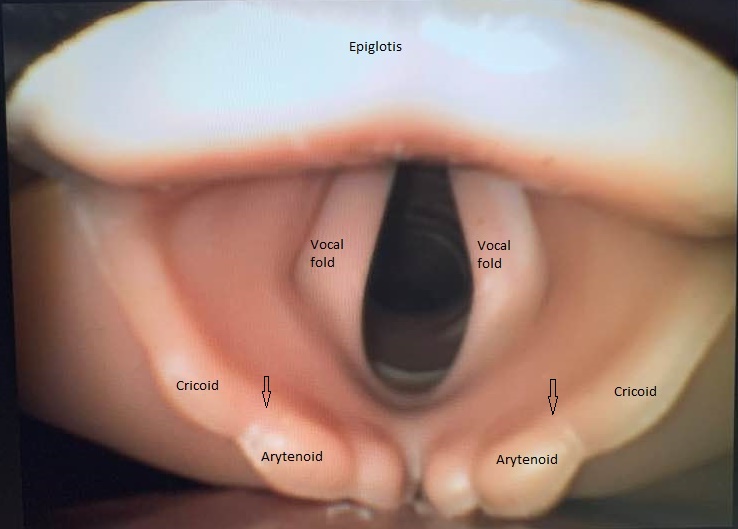

The larynx is situated just below the pharynx. It is comprised of three paired smaller cartilages, three unpaired cartilages, and the intrinsic muscles. The three paired cartilages include the arytenoids, corniculate, and cuneiform. The three unpaired cartilages include the cricoid, thyroid, and epiglottis. The cricoid cartilage is the only cartilage that covers the circumference of the trachea. The epiglottis, which is superior to the cricoid cartilage, is an important landmark for direct laryngoscopy. The epiglottis is located at the base of the tongue and encapsulates the glottis to form a lid over it. The epiglottis protects the larynx from the aspiration of gastric contents. At the base of the tongue, anterior to the epiglottis is a pocket of cartilage known as the vallecula. The vallecula is an equally important landmark, as certain types of direct laryngoscopy blades, such as the curved or Macintosh blade, are inserted into order to manipulate the area to improve visualization of the vocal cords. When the laryngoscope blade is in the vallecula, it is pressed up against the hyoepiglottic ligament, which suspends the epiglottis from the hyoid bone.

Indications

Direct laryngoscopy to perform endotracheal intubation is indicated in the emergent setting in perioperative settings or the intensive care setting. In the emergency room, the indications for direct laryngoscopy to perform endotracheal intubation include acute respiratory failure, impending airway collapse indicated by hypoxia or hypercapnia, and airway protection in patients with altered or depressed mental status, upper gastrointestinal bleeding or hematemesis secondary to bleeding from esophageal varices.[4] In the perioperative setting, endotracheal tubes can be placed using direct laryngoscopy for patients receiving general anesthesia, surgeries involving the airway or areas adjacent to it, or surgeries involving unusual positioning, such as spinal surgery, which requires prone positioning.[5] In the intensive care unit, direct laryngoscopy for endotracheal intubation is performed for impending airway collapse, or short-term hyperventilation of patients with increased intracranial pressures in the setting of intracranial hemorrhage, tumors or masses. Intubations in the intensive care unit are also performed to manage copious secretions.[6]

Contraindications

Direct laryngoscopy has few absolute contraindications. Such absolute contraindications involve supraglottic and glottic lesions that would prohibit the advancement of the endotracheal tube (ETT) such as high-grade subglottic or glottic stenosis or complete obstruction by supraglottic or glottic tumors. Additionally, blunt trauma to larynx resulting in laryngeal fracture or disruption of the laryngotracheal junction can become worse in the setting of traction from laryngoscope blade, placement of the ETT or pressure from the ETT stylet, which can promote the creation of a false lumen in the trachea or cause perforation through the trachea.[7] In these patients, a surgical airway is required.

Direct laryngoscopy for ETT placement is also contraindicated in the case of penetrating trauma to the upper airway, in which manipulation of the area by laryngoscope or ETT may cause a hematoma, partial or complete transection of the airway. In such suspected cases, ventilation and oxygenation should be accomplished via non-invasive means until a definite surgical airway is established.[8]

Grade III trismus (inter-incisoral distance of <1 cm) is an absolute contraindication to direct laryngoscopy, though, in practice, direct laryngoscopy is rarely possible with grade II trismus either.

In addition to blunt and penetrating traumas of the airway, conditions such as infections, burns, or anaphylaxis, which can lead to severe edema and swelling of the larynx or supralaryngeal are also relative contraindications for direct laryngoscopy. This is because visualization of the vocal cords and entrance of the airway might not be possible, and trauma and irritation caused by the laryngoscope blade and/or ETT can exacerbate by the swelling and edema of the airway, which can limit the efficacy of bag-mask valve oxygenation and ventilation.[8] In such settings, direct laryngoscopy should only be attempted if preparations are in place for an immediate surgical airway if intubation is unsuccessful.

Relative contraindications to laryngoscopy include difficulties in performing the procedure, such as patients with difficult airways (i.e., micrognathia, macroglossia, high Mallampatti score), injury, and trauma of the neck, pharynx, or larynx. In addition, patients with airborne diseases who require their airway secured, for example, those with Tuberculosis, COVID19, Ebola, to name a few, should not undergo direct laryngoscopy if possible due to transmission of the pathogen to healthcare personnel. In those patients, video laryngoscopy (or a modified protocol to minimize aerosolization) is recommended.[9][10]

Equipment

Before direct laryngoscopy can begin, it is important to place the patient on cardiac monitoring and a continuous pulse oximeter, the suctioning device should be prepared and accessible for immediate use, appropriate lighting and positioning of the patient as successful preparation of patient and equipment are equally important to the procedure.[11]

Direct laryngoscopy and subsequent endotracheal intubation require a laryngoscope handle, blades (Macintosh or curved, Miller, or straight with a curved end, Jackson-Wisconsin or straight), appropriate sized ETT with a stylet and an ETT one size bigger and one smaller. Most tracheal intubations in an emergency or perioperative setting in adults can be accomplished with 7.5 mm cuffed tubes. In the intensive care setting, larger tubes are preferred as these make tracheal suctioning and flexible bronchoscopy possible through the ETT; in addition, larger tubes cause less resistance to flow of air through a ventilator, but the tube must not be so large as to increase risk of arytenoid injury or subglottic stenosis. In addition to a laryngoscope, blade, and ETT, appropriate equipment includes sterile lubricant for the ETT cuff and balloon and at least a 10 cc syringe to inflate the ETT balloon after successful placement.[12]

Equipment for direct laryngoscopy also includes adjunct airway management devices such as a "Bougie," which is an ETT introducer, oral and nasal airways, and rescue airway devices such as a Combitube or supraglottic airway tubes. An end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor (capnography) is required to help confirm the appropriate placement of the ETT. Lastly, all direct laryngoscopy equipment includes back-up devices to access the airway, such as video laryngoscopes[13], rescue airway devices (laryngeal mask airway) and if nothing works, a cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy tray. If a difficult airway is known or suspected, the instruments for a surgical airway should be opened and ready before beginning laryngoscopy.

Personnel

The personnel involved in direct laryngoscopy can come from multiple departments within the hospital. The emergency department physicians can use it for intubating critical patients. Anesthesiologists regularly use this technique in the operating room during endotracheal intubations. Critical care physicians also use this method when they need to protect the airways of their patients. Otolaryngologists or general surgeons may be needed if there is a higher risk of a surgical airway.

Preparation

In preparation for the procedure, one must first assess the patient. Some patients may prove to be more difficult candidates for successful endotracheal intubation with direct laryngoscopy. The following traits all can lead to more difficult visualization of the larynx with direct laryngoscopy, making a patient a less than ideal candidate:

- Interincisor gap of fewer than 4 centimeters

- A thyromental distance of less than 6 centimeters

- A sternomental distance of less than 12 centimeters

- Head and neck extension of less than 30 degrees from neutral

- Mallampati class 3 or 4

- Mandibular retrusion (micrognathia or true retrognathia)

- Neck circumference of greater than 40 centimeters

- Submental compliance

- History of cervical spinal fusion

- Radiation or burn contracture in the neck

Once the patient is adequately assessed, the patient must be pre-oxygenated. If a patient is a difficult intubation or at risk for rapidly desaturating, one can pre-oxygenate using apneic oxygenation. Apneic oxygenation is achieved by using passive oxygen insufflation via nasal cannula at 15 liters per minute. Another important part of the preparation is to keep a functioning suction device and bag-valve-mask nearby. Monitoring devices such as blood pressure, pulse oximetry, continuous cardiac monitoring, and capnography should be appropriately connected to the patient. Next, intravenous access should be established. A final preparation step is to ensure that induction agents, neuromuscular blocking agents, adjunctive medications, and emergency medications are prepared, as well as instruments are at the ready for surgical airway if the patient is a suspected difficult airway.

Technique or Treatment

Successful direct laryngoscopy involves multiple steps.[14]

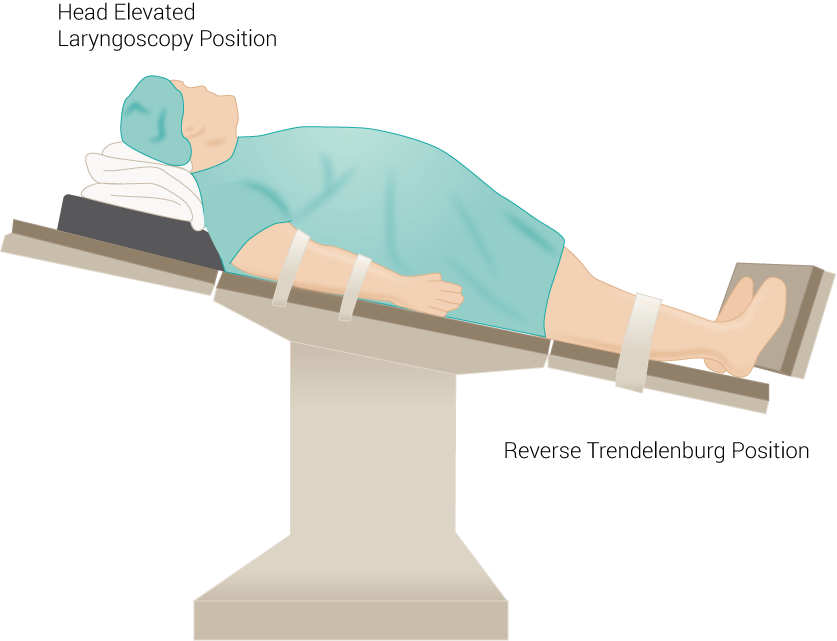

- One must first properly position the patient. The classic position is the “sniffing” position where the atlanto-occipital extension with a head elevation of three to seven centimeters; however, patients with cervical spine injury should not have head and neck manipulation performed.

- Next, one must open the patient’s mouth by using the right hand. An effective method is by using the scissor technique. This is performed by flexing the thumb and middle finger past each other, with the thumb pressing on the mandibular dentition and the middle finger pressing on the maxillary dentition.

- The laryngoscope is then inserted in the right side of the mouth, and the blade is then used to sweep the tongue to the left, then the blade is smoothly advanced to the epiglottis. If a Macintosh blade is used, it is advanced to the vallecula, and if a Miller blade is used, it is advanced over the epiglottis to the entrance of the trachea proximal to the vocal cords.

- The laryngoscope is then moved anteriorly to reveal the vocal cords.

In the cases of very anterior airways, mild-to-moderate cricoid pressure can be applied by an assistant while lifting the laryngoscope to help visualize the airway.

Complications

As in many procedures, complications may arise. The laryngoscope may cause blunt or penetrating trauma to the oropharynx, larynx, and trachea or may chip teeth or lacerate the lips. Direct laryngoscopy involves the possibility of vocal cord damage as well as arytenoid cartilage dislocation. Meticulous technique is required at all times to avoid these complications.

The most common complication of this procedure is a sore throat, which is reported to occur in 14% to 57% of patients who undergo intubation for general anesthesia. Sore throat is a broad definition but includes pain, discomfort, hoarseness of voice, dysphagia, and dry throat; these can occur alone or in a combination. Sore throat is usually mild and temporary and mostly resolves within 48 hours.[15]

Complications of direct laryngoscopy and subsequent ETT placement can be classified into two categories: traumatic and non-traumatic. Traumatic injuries can include a direct blunt or penetrating trauma to the trachea, larynx, or oropharynx from either the laryngoscope blade, the ETT style, or the ETT itself. The damage can also occur to the lips, tongue, pharynx, esophagus, and teeth.[16] Chipped and broken teeth as a result of improper technique are a major complication to be wary of. In addition, the ETT can cause glottic trauma and cause damage to and paralysis of the vocal cords and dislocation of the arytenoid cartilages.[17] In rare instances, extreme flexion or extension of the neck during direct laryngoscopy can cause cervical spinal cord injuries in patients that have risk factors, such as patients with unstable cervical spinal column fractures, severe rheumatoid arthritis, or atlantoaxial instability.[18] Temporomandibular joint dislocation can happen in rare instances if excessive force is used to displace the mandible for laryngoscopy.

Nontraumatic complications of direct laryngoscopy and ETT placement include aspiration of gastric contents[19], hypoxic brain injury from a prolonged attempt at intubation without adequate oxygenation[20], and bronchospasm.[21] Sympathetic surge causing tachycardia, dysrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, and/or infarction and hypertension can occur as a result of stimulation of the highly innervated glottis by the laryngoscopy blade.[22] Similarly, especially in younger patients, the laryngoscopic blade can stimulate the vagus nerve, which can cause profound bradycardia.[23] Esophageal intubation is also a well-recognized complication of direct laryngoscopy and is usually quickly recognized and corrected.[24] Barotrauma, pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, and hypotension are also well-known atraumatic complications of direct laryngoscopy.[25]

Tracheal intubation can have chronic and long-term complications as a result of the irritation to the tissue, causing scarring, which can lead to laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, tracheomalacia, or laryngeal stenosis (both glottic and subglottic).[26]

Clinical Significance

Direct laryngoscopy is a useful tool to gain mastery of for use in various settings of the hospital and is the mainstay technique for safe intubation and laryngeal surgery. Its application ranges from emergent scenarios requiring airway protection to routine use in the operating room. A secured airway with adequate oxygenation and ventilation can help with the resuscitation of a patient, can minimize perioperative and postoperative complications, and can help critically ill patients by ensuring adequate oxygenation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A direct laryngoscopy allows visualization of the larynx and is often used during general anesthesia, surgical procedures around the larynx, and resuscitation. This tool is useful in multiple hospital settings, from the emergency department to the intensive care unit and the operating room. By visualizing the larynx, endotracheal intubation is facilitated. Even though a minor procedure, one must be well acquainted with the anatomy, indications, contraindications, equipment, and personnel for the successful use of direct laryngoscopy.