Continuing Education Activity

Diffuse esophageal spasm is an esophageal motility disorder that often manifests as dysphagia. If the diagnosis is delayed, diffuse esophageal spasm is associated with high morbidity. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of diffuse esophageal spasms and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of diffuse esophageal spasm.

Identify the typical presentation of a patient with diffuse esophageal spasm.

Explain the techniques used to diagnose diffuse esophageal spasms.

Explain the need for improved care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to enhance the delivery of care and improve outcomes for patients with diffuse esophageal spasms.

Introduction

Diffuse esophageal spasm (DES) is a rare esophageal motility disorder characterized by simultaneous, uncoordinated, or rapidly propagated contractions that are of normal amplitude and accompanied by dysphagia.[1] It is defined manometrically as simultaneous contractions in the smooth muscle of the esophagus alternating with normal peristalsis in over 20% of wet swallows with amplitude contractions of greater than 30 mmHg. However, after the introduction of high-resolution esophageal pressure topography, the defining criteria for DES has been changed, and is the presence of at least two premature contractions with a distal latency of under 4.5 seconds in a context of normal esophagogastric junction relaxation.[2]

Etiology

The etiology of diffuse esophageal spasm is unknown. There are various theories proposed.

There is a disruption of coordination in peristalsis, which is probably due to an imbalance between the inhibitory and excitatory postganglionic pathways. Muscular hypertrophy or hyperplasia is present in the distal part of the esophagus, comprising almost two-thirds of the esophagus in DES. Although the triggering event is unknown, the Increased release of acetylcholine might be a factor. Other theories include nitric oxide-mediated impairment of inhibitory ganglion neuronal function, gastric reflux, or a primary nerve or motor disorder as likely mechanisms of the peristaltic abnormalities seen in DES.[3]

Exposure to acid can also result in esophageal spasms, whereas heartburn can lead to esophageal contractions.[4][5]

There have also been suggestions that total cholesterol and body mass index (BMI) are factors that have a high predictive value for esophageal contractility; at the same time, blood glucose and BMI are factors predictive for the function of the lower esophageal sphincter.[6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of diffuse esophageal spasm is around 1 case in 100000 population per year. Esophageal spasm appears to be more common in people of the White race as compared to other races and presents more frequently in women. Its incidence increases with age and is rarely seen in children. It has a prevalence of 4 to 7%, according to the data collected from referral centers.[7]

Pathophysiology

The food bolus is transported from the mouth to the stomach in ten seconds; this takes place due to the peristaltic contractions of the body of the esophagus. Dysphagia may alternately increase and decrease.

The diffuse esophageal spasm occurs due to defective propagation of peristaltic waves through the esophageal wall. Several segments of the esophagus contract independently of each other simultaneously, thus causing improper propagation of the food bolus in DES. It is thus characterized by quick wave progression through the esophageal wall and distinguished as a non-peristaltic wave during swallowing. However, many cases are thought to be caused by uncontrolled brain signals running to nerve endings.

Increased release of acetylcholine is thought to play a major role in diffuse esophageal spasm, but what causes the release of the neurotransmitter is not known. Other hypothesis link diffuse esophageal spasm to reflux, elevated BMI, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. The classic presentation is a patient with episodic chest pain and intermittent dysphagia. Myotomy is only done in extreme cases, but the relief of symptoms is not always guaranteed.

History and Physical

The typical clinical features that a patient with diffuse esophageal spasm presents with are:

1. The most prominent and imminent feature for DES is the presentation of dysphagia that can occur with both solids and liquids.

2. Globus hystericus, in which the patient presents with a sensation of an object getting trapped on the back of the throat.

3. Chest pain, which is noncardiac in nature, retrosternal in presentation, and with the possibility of radiating to the back. It accounts for less than 10% of cases of noncardiac chest pain. In some instances, it can even present with a much more severe presentation than characteristic anginal features.

4. Patients with DES can also complain of occasional regurgitation of undigested food.

5. The association of DES with GERD can also lead to heartburn which can sometimes lead to a challenging diagnosis.[3]

The usual presentation is intermittent dysphagia with occasional chest pain. Pain might manifest upon eating quickly or consuming hot or cold beverages. DES is commonly associated with comorbidities like anxiety and depression.

Evaluation

Evaluation of non-cardiac chest pain in older patients, males, white race, and those presenting with dysphagia are candidates for esophageal function testing.[8]

Dysphagia is reproducible on investigative studies such as esophageal manometry.[9]

Twenty-four-hour manometry is the best modality to diagnose DES as a cause of noncardiac chest pain and should be combined with endoscopy and barium swallow to rule out any kind of inflammation and neoplasia in the esophagus.[10]

Findings on manometry are:

1. Aperistalsis in greater than 30% of the wet swallows

2. 20% simultaneous contractions

3. The amplitude of the contractions in the distal three-fifths of the esophagus is greater than 30%.

Although the diagnosis is usually made by means of esophageal manometry, tests like endoscopy and barium swallow are helpful in excluding inflammatory or neoplastic changes.[9]

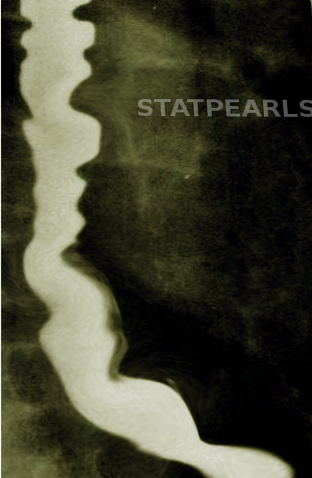

Diffuse esophageal spasm has a characteristic corkscrew or rosary beads appearance, which reflects abnormal contractions that leads to compartmentalization and curling of the esophagus, thus giving the classic finding in barium studies.[11]

The introduction of newer techniques like high-resolution manometry (HRM) and esophageal pressure topography (EPT) has significantly enhanced the ability to diagnose DES.[3]

Studies using catheter-based high-frequency ultrasound imaging have shown an increase in the baseline muscle thickness in patients with diffuse esophageal spasms.

To make the diagnosis clear, diseases such as diabetes, which can also present with similar symptoms, should also be ruled out using blood glucose and HbA1C levels.

Treatment / Management

Current treatment agents include nitrates (both short and long-acting), calcium-channel blockers, visceral analgesics (tricyclic agents or SSRI), and esophageal dilation.[2] First-line therapy is with calcium channel blockers and nitrates. Endoscopic botulinum toxin injection and pneumatic dilation are second-line therapies.[3]

Concomitant gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should also receive treatment, especially if the esophageal testing shows pathologic reflux. Initiation of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) half an hour before meals can help relieve GERD symptoms. Patients who are responsive to PPIs will continue with PPI therapy for three months.

Botulinum toxin injection is also considered an effective and low-risk procedure for short-term symptom relief. It is usually only an option for medically high-risk patients[12]

Selected cases may receive treatment with extended myotomy of the esophageal body or peroral endoscopic myotomy. Myotomy should involve the entire length of the affected segment (determined preoperatively with manometry) and extend several centimeters superior to the proximal border of the spastic region to prevent remnants of spasticity.[13] It should also extend through the lower esophageal sphincter to prevent dysphagia by preventing outlet obstruction postoperatively. An antireflux procedure like a partial wrap or a Nissen fundoplication can be performed concomitantly. Most patients with dysphagia as the primary symptom improve after a myotomy.[14]

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is a safe and effective treatment for patients, especially those who are refractory to medical therapy.[15][16][17]

Heller myotomy combined with fundoplication is a rare alternative for the refractory patient.

Patients with DES and other esophageal motility disorders who suffer from psychiatric illnesses like anxiety and depression as well can receive tricyclic antidepressant therapy. They improve esophageal as well as psychological symptoms, leading to better outcomes.

Initiation or change in therapy requires adequate follow-up care by the physician. The efficacy of the medication in terms of improvement of the symptoms requires close monitoring, and any serious adverse effect should be identified and managed. If medical management of the patient fails, the patient is a candidate for surgical treatment with a referral to a thoracic surgeon.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of diffuse esophageal spasms include:

Prognosis

Due to the marked improvement in symptoms over 3 years, the prognosis of diffuse esophageal spasm is a moderate one.

The appropriate workup for DES should ensue as chest pain can mimic cardiac, pulmonary, and rheumatological disorders.

The chances of mortality with DES is low, but it can significantly hamper the quality of life in a patient and can lead to high morbidity in these patients. The increase in the rate of morbidity can be due to:

1. Decreased ability to eat, which is mostly secondary to the associated pain

2. The incapacitating pain can lead to a marked reduction in normal activity which can further challenge the patient emotionally as well as physiologically.

3. The nutritional status of the patient is significantly affected.

The main principle behind counseling the patient of DES should be to relieve the plethora of psychosocial and emotional aspects that present with this disorder, and the patient should have reassurance about the positive aspects and how appropriate monitoring can lead to normalizing of the quality of life.

Complications

The therapeutic interventions hold the potential adverse reactions for which the patients should have regular monitoring.

The most dreaded complication of esophageal perforation after esophageal dilation can warrant hospital admission and the possible need for surgery. Suspected esophageal perforation with marked hematemesis, pneumoperitoneum, electrolyte abnormalities, and possible vagal injury require urgent surgical intervention to close the defect.

Also, before starting oral refeeding, the patient should undergo a contrast-swallowing test to check for any possible leak, which would require immediate management.

Possible complications of wound infection, atelectasis, pneumonia, and air leak post-op should be kept high on clinical suspicion and should be addressed appropriately.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is critical in terms of the identification of symptoms and available treatment options for the disease. The treatment modality will be successful only with complete patient education and involvement.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diffuse esophageal spasms usually present with chest pain and dysphagia. Although it may sometimes present with regurgitation and heartburn as well, the etiology is still unknown. A general physician and nurse practitioner are mostly involved in the medical management of the patient, but a professional team consisting of an internist, gastroenterologist, radiologist, and general surgeon should have involvement for refractory cases and patients requiring surgical treatment. A full interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, need to communicate across their disciplines to provide the best care and increase the odds of a positive outcome. [Level 5] Proper communication among the interprofessional team, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists, ensures complete and successful management of the patient. Patient education leads to timely follow-up and medication compliance, which is essential to minimize morbidity and enhance the quality of life.