Continuing Education Activity

Dermatofibroma, also known as fibrous histiocytoma, is a common, benign, cutaneous soft-tissue lesion characterized by firm subcutaneous nodules, typically measuring 1 cm or less in diameter. Dermatofibromas are commonly found on the extremities and are prevalent across all age groups. However, they are more frequently observed in individuals aged 20 to 50, especially among females. Although the exact cause of the condition remains unknown, it is common for patients presenting with a dermatofibroma to report a history of local trauma at the site, such as from an insect bite, minor injuries, or superficial puncture wound.

Dermatofibromas are typically asymptomatic but may sometimes cause pain, tenderness, or itchiness. Diagnosis involves histopathological examination, which correlates well with sonographic findings. Treatment is generally unnecessary unless the lesion is symptomatic, though excision is recommended for suspicious or atypical cases. Complications of surgical removal may include bleeding, infection, and scarring. This activity reviews the clinical manifestations, epidemiology, histopathology, diagnostic modalities, and differential diagnoses of dermatofibromas, which are crucial for accurately distinguishing dermatofibromas from other cutaneous neoplasms, notably dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, to ensure appropriate management strategies. This activity also emphasizes the vital role of the interprofessional healthcare team in enhancing patient outcomes by raising awareness of dermatofibroma and ensuring preparedness in effectively managing these cases. A multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals is essential for ensuring accurate diagnosis, effective management, and optimized patient outcomes of dermatofibroma.

Objectives:

Identify dermatofibroma accurately based on clinical presentation, histopathological findings, and imaging studies.

Implement appropriate diagnostic and treatment modalities for dermatofibroma, including biopsy, imaging, and multidisciplinary management.

Apply evidence-based guidelines and treatment protocols for dermatofibroma management, considering patient-specific factors and tumor characteristics.

Collaborate with the interprofessional healthcare team, including dermatologists, oncologists, and pathologists, to optimize dermatofibroma, provide well-coordinated care, and enhance patient outcomes.

Introduction

Dermatofibroma, also known as fibrous histiocytoma, is a common, benign, cutaneous soft-tissue lesion characterized by firm subcutaneous nodules. The term "fibrous histiocytoma" primarily describes the morphologic appearance of the cell populations forming these lesions rather than solely indicating the cellular lineage. Clinically, these mesenchymal cell lesions of the dermis are commonly found on the extremities and are relatively small, typically measuring 1 cm or less in diameter. Dermatofibromas are prevalent across all age groups; however, they are more frequently observed in individuals aged 20 to 50, especially among females.

Dermatofibromas are typically asymptomatic but may sometimes cause pain, tenderness, or itchiness. The lesions represent a benign dermal proliferation of fibroblasts. Despite the unknown pathogenesis, sometimes dermatofibroma may occur due to insect bites, trauma, minor injuries, or superficial puncture wounds. Although dermatofibromas are benign tumors, cases of local recurrence and, even more rarely, distant metastases have been reported. Therefore, when considering the differential diagnosis of these lesions, it is crucial to distinguish dermatofibroma from dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP)—a similar-appearing but more aggressive cutaneous neoplasm.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

The nature of dermatofibroma as either a reactive process or a true neoplasm remains unclear. Although the exact cause of the condition remains unknown, it is common for patients presenting with a dermatofibroma to report a history of local trauma at the site, such as from an insect bite, minor injuries, a rose thorn injury, or a superficial puncture wound, but not consistently. While patients diagnosed with dermatofibroma often report a history of local trauma, suggesting a reactive process, such trauma is not consistently reported and is found in only about one-fifth of cases. More often, dermatofibromas develop spontaneously without any specific inciting event or trauma. Spontaneous regression is rare, which may argue against a primarily reactive process and instead support a clonal or neoplastic model.

Dermatofibroma lesions consist of proliferating fibroblasts, often with the involvement of histiocytes. Some studies have detected clonal markers in dermatofibroma cells through analysis of X chromosome inactivation, suggesting a monoclonal pattern and potentially supporting a neoplastic origin of development. Conversely, others suggest a heterogeneous derivation of dermatofibroma, positing that it represents both reactive and neoplastic processes within the same lesion. In this model, the histiocytoid component may be neoplastic, while the fibrous portion may arise from reactive fibroblastic proliferation.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

According to a study, dermatofibroma is a prevalent skin lesion found across almost all populations, constituting approximately 3% of all dermatopathology laboratory specimens. Determining its global incidence is challenging as most patients are asymptomatic and may not seek medical attention. These lesions commonly manifest in individuals aged from their 20s to their 40s. Although most studies suggest a female predominance, the incidence varies from equivocal to slightly higher, potentially twice as frequent in females as males.[4][5][6]

Histopathology

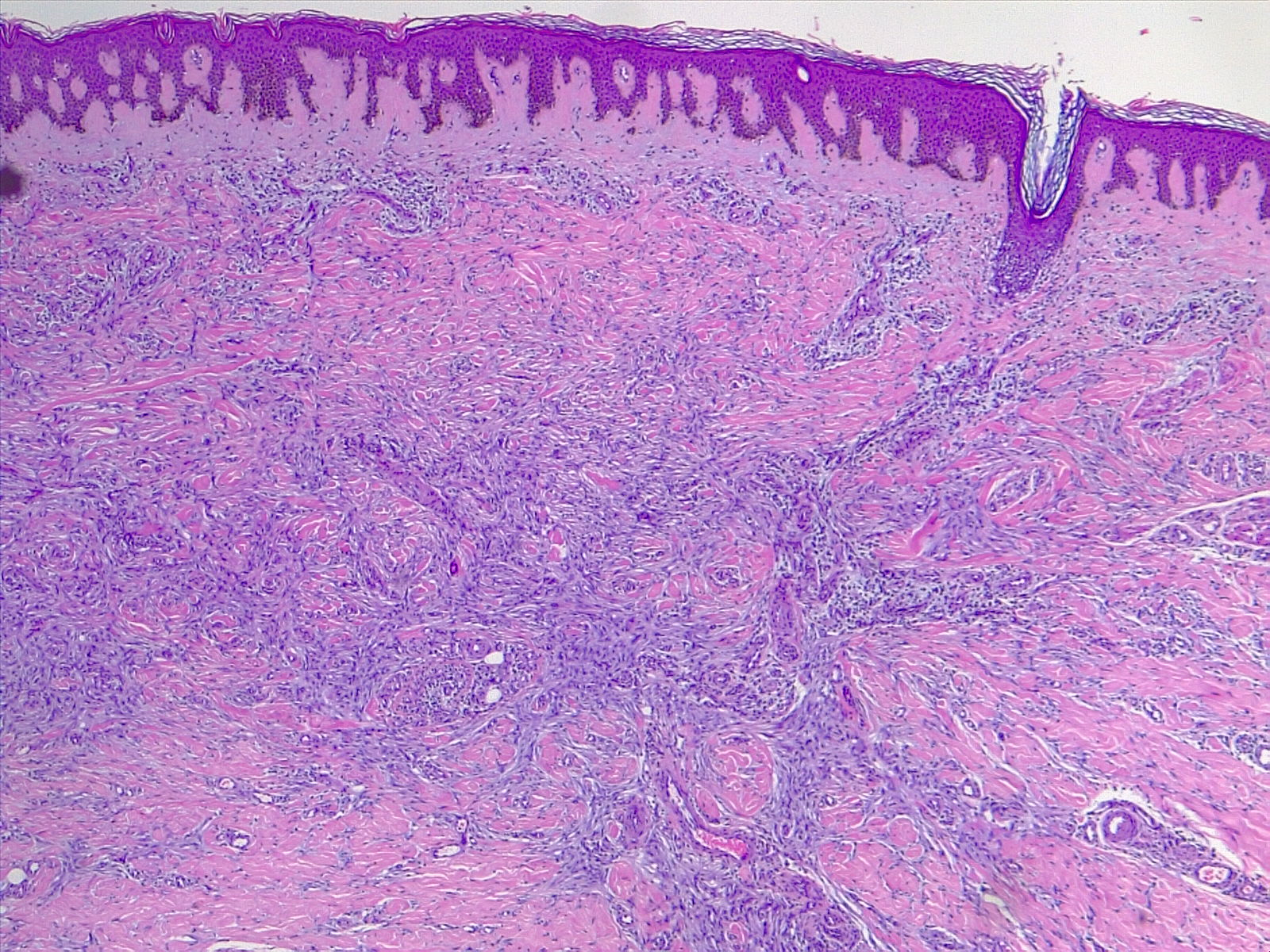

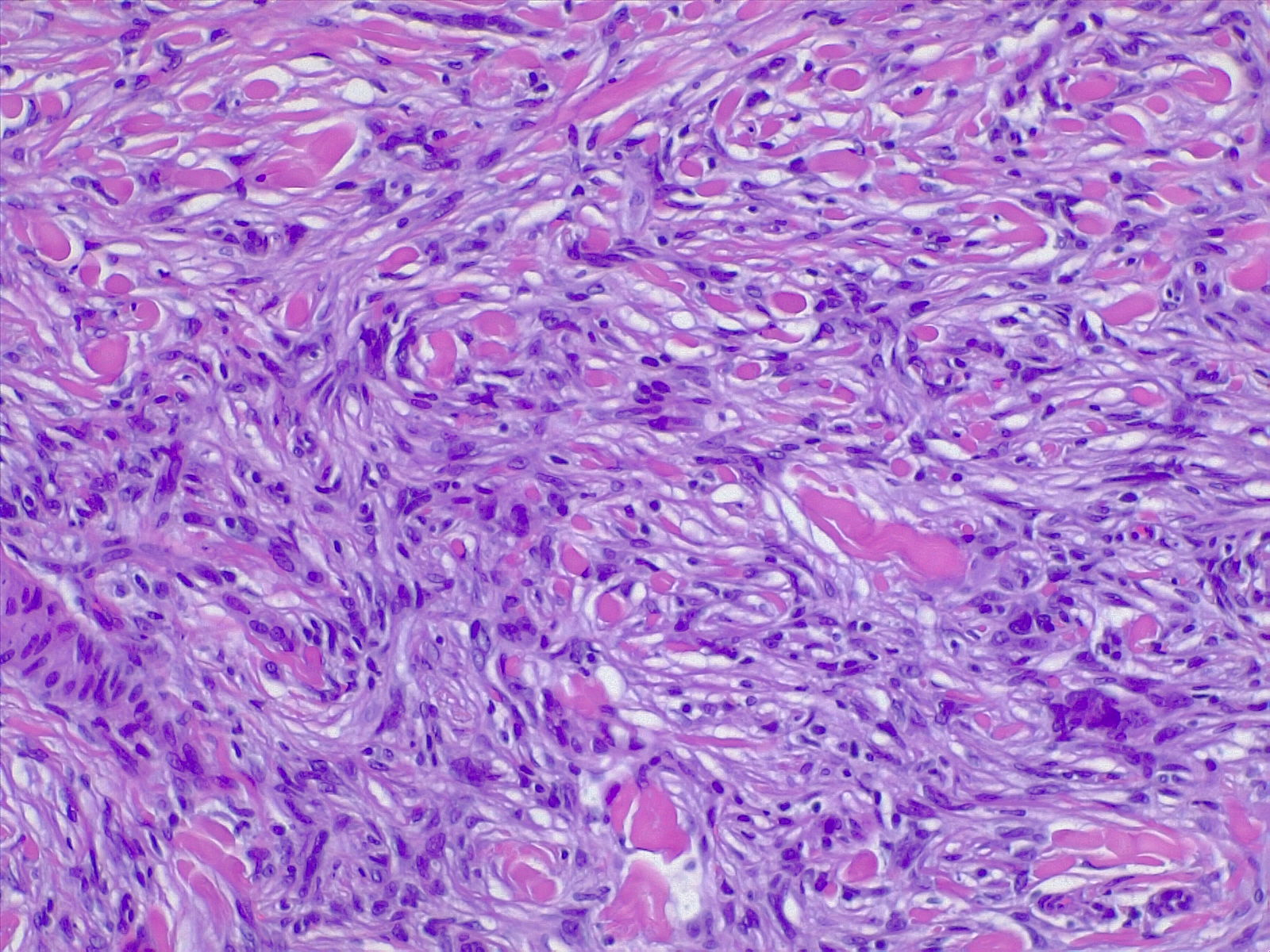

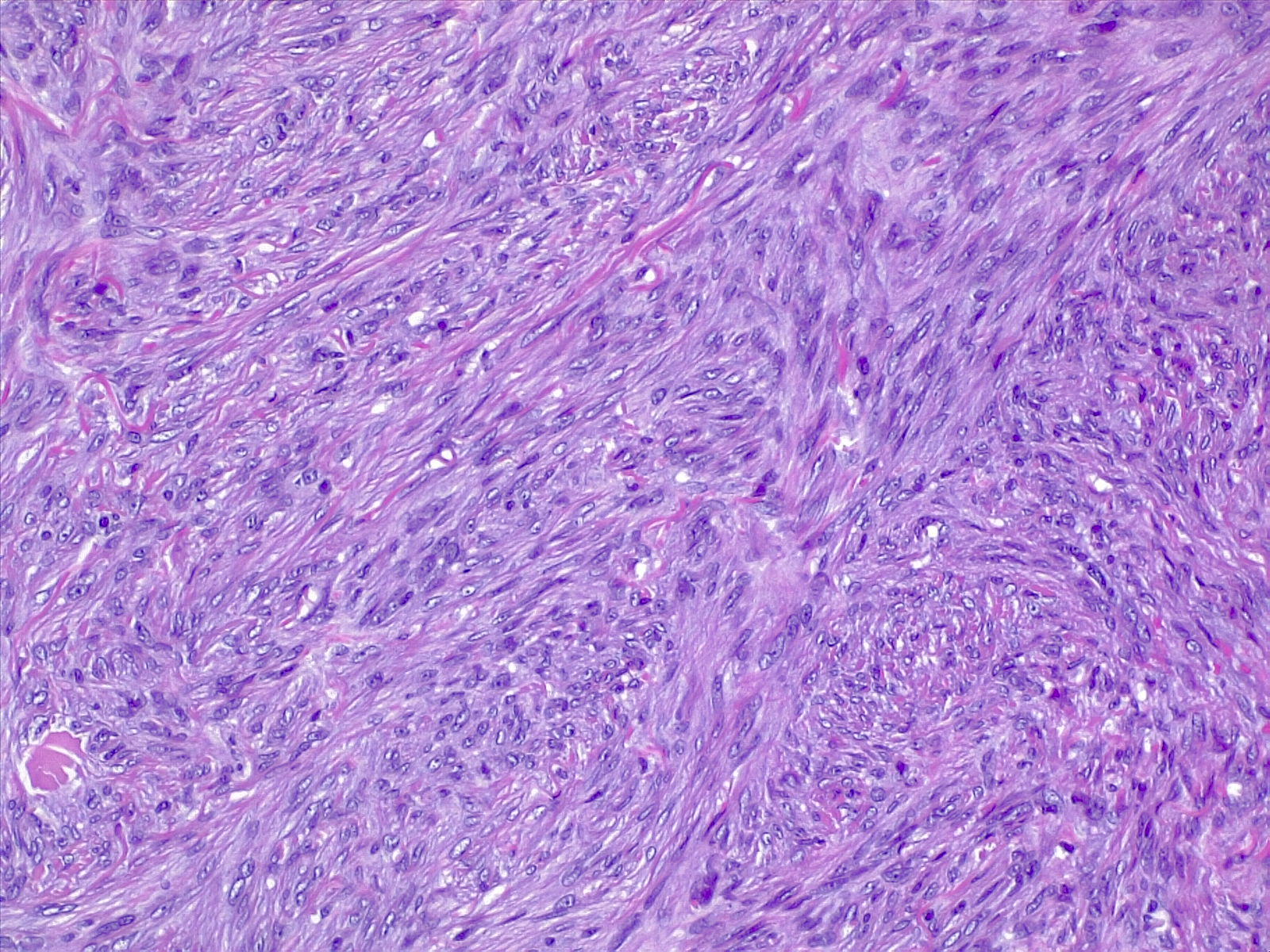

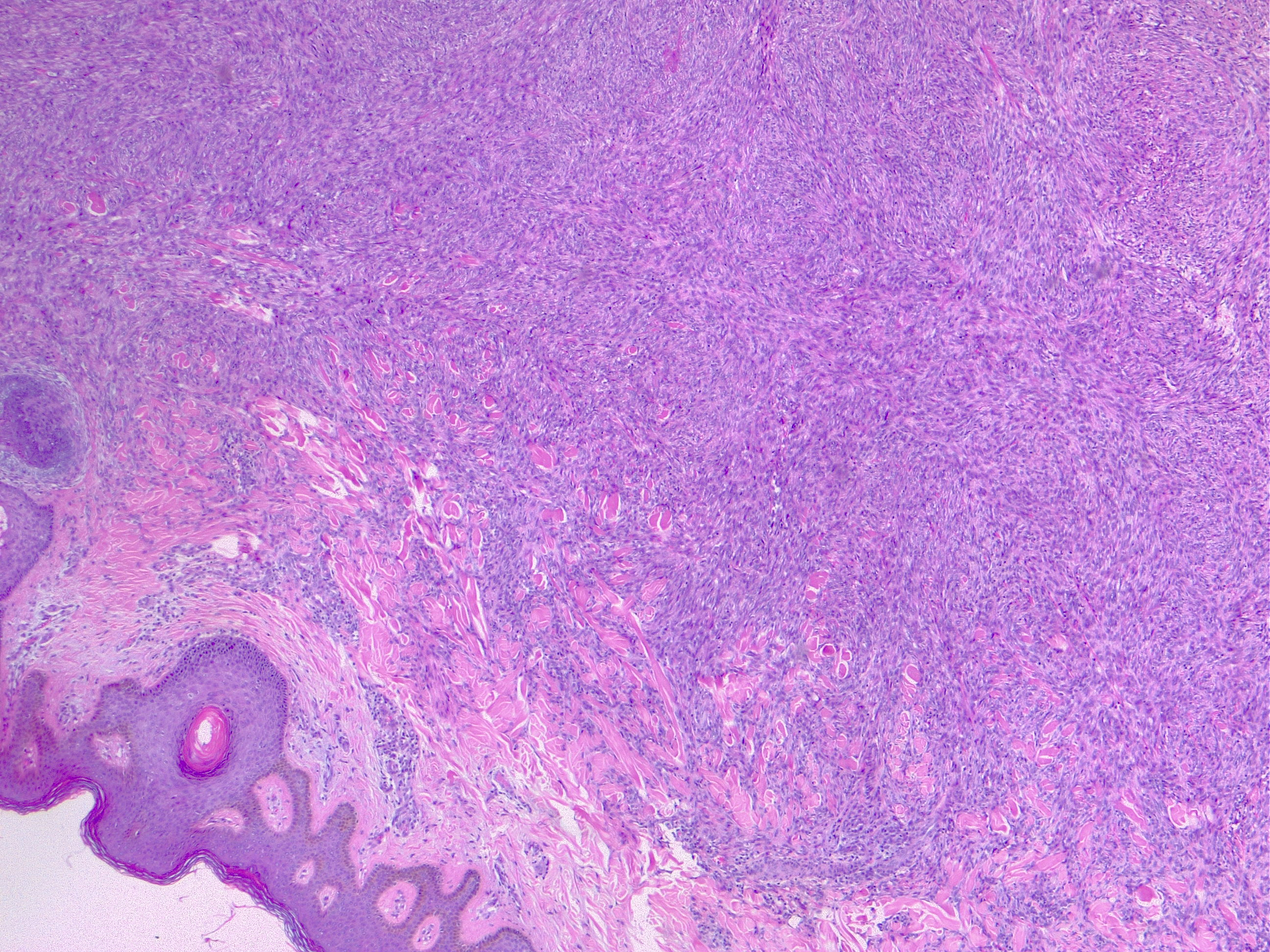

The most commonly diagnosed histologic variant of dermatofibroma is the common fibrous histiocytoma, also known as common dermatofibroma. Histopathologically, common dermatofibroma is characterized by a localized proliferation of spindle-shaped fibrous cells mixed with histiocytoid cells within the dermis. Typically nodular in appearance, these proliferations exhibit spiculated but moderately defined borders that may appear to push against surrounding tissue. The spindle cells may form a focal storiform pattern characterized by a multicentric whorling appearance of elongated nuclei. Intermixed capillaries, lymphocytes, or multinucleated giant cells may also be present. While these proliferations typically remain within the dermis, it is common to observe a small portion of the lesion extending into the subcutaneous tissue along septal lines.

A distinguishing characteristic of dermatofibroma is the presence of trapped collagen bundles or collagen balls within and between the fascicles of spindled fibrous cells. These entrapped collagen collections are frequently located at the periphery of the lesion. A delineated and unaffected zone typically separates the overlying epidermis—the Grenz zone. Reactive changes in the epidermis commonly include hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. Additionally, the epidermis often displays elongated rete ridges extending into the dermis, with hyperpigmented basal keratinocytes, a feature referred to as the "dirty-feet sign."

Arguably, the most crucial distinction is between dermatofibroma and the more concerning DFSP, which bears a similar appearance. DFSP lesions are typically more cellular, exhibiting pronounced storiform patterns and deep invasion into the subcutis, often entangling fat as it proliferates along subcutaneous septae.[7][8][9] Dermatofibroma stains positive for factor XIIIa and vimentin but is negative for CD34.

Types of Dermatofibromas

Various uncommon histologic variants of dermatofibroma are mentioned below.

Atypical dermatofibroma: Atypical dermatofibroma, also known as atypical fibrous histiocytoma or dermatofibroma with monster cells, is a rare variant of dermatofibroma. This variant is characterized by a mixture of pleomorphic cells with large, bizarre, hyperchromatic nuclei within a background of typical spindle cells arranged around thick collagen bundles.[10]

Cellular benign dermatofibroma: Cellular benign dermatofibroma, also known as cellular fibrous histiocytoma, is characterized by a dense proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue and exhibit normal mitotic figures. Lesions excised with involved margins have been reported to have a recurrence rate of 10%.[11]

Epithelioid dermatofibroma: Epithelioid dermatofibroma comprises large, angulated epithelioid cells resembling the cells found in the intradermal Spitz nevus.

Aneurysmal dermatofibroma: Aneurysmal dermatofibroma is a rare type of mesenchymal tumor originating from fibroblast and histiocytic cells within the dermal layer of the skin. This variant typically presents as blue, red, or purple papules commonly found on the lower extremities. These lesions are often clinically misdiagnosed as vascular lesions. Histologically, they consist of spindle-like cells with interspersed collagen bundles and typically exhibit blood-filled tissue spaces along with hemosiderin deposition in the surrounding cells.

Hemosiderotic dermatofibroma: Hemosiderotic dermatofibroma, also known as hemosiderotic fibrous histiocytomas, may be associated with aneurysmal dermatofibroma. These lesions are characterized by the presence of small blood vessels and extravasated red cells with hemosiderin deposition. They may be mistaken for melanoma or other pigmented lesions due to their appearance.[12]

In patients with 2 or more simultaneously occurring dermatofibromas, the lesions typically appear histopathologically similar, despite the existence of multiple histologic benign variants of dermatofibroma.

History and Physical

Dermatofibromas are slow-growing lesions that can develop on any part of the body, although they commonly affect the extremities. Clinically, they present as firm, nontender cutaneous nodules with or without accompanying skin changes, such as tan-pink to reddish-brown discoloration, which may vary depending on the age of the lesion. Typically, dermatofibromas measure 1 cm or less in diameter, but larger lesions exceeding 3 cm in diameter have been documented.

Lesions are typically asymptomatic but may occasionally be pruritic and tender. Approximately 1 out of 5 cases involve a history of local trauma at the site of the lesion, such as vaccination or an insect bite. A thorough full-body skin examination is crucial as these lesions may be subtle, with multiple lesions present in 10% of cases. A characteristic finding upon examination is the "dimple sign," where lateral inward digital pressure on the skin produces central dimpling over the lesion due to its fixation to the subcutaneous tissue.[8][9]

Multiple "eruptive" dermatofibromas have been observed in various clinical contexts, including patients with autoimmune diseases receiving immunosuppressive therapies, individuals with HIV infection, and pregnant women.[13][14][15] In addition, rare familial cases inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern have also been reported.[16]

Diagnosis of dermatofibromas is typically based on clinical appearance and history. Longstanding lesions should not exhibit a history of rapid change. Metastasizing benign dermatofibromas are exceedingly rare. They are generally larger in size (>3 cm) than common dermatofibromas. These dermatofibromas may morphologically display features of cellular, aneurysmal, or atypical dermatofibroma, along with an increased number of mitotic figures and extension into the subcutaneous tissue.[17][18]

Multiple clustered dermatofibroma is an exceedingly rare variant of dermatofibroma, which manifests as a plaque consisting of numerous (>15) individual reddish to hyperpigmented papules, typically found on the lower extremities.[19] This variant is commonly observed in children and young adults and may be either congenital or eruptive.[20] The differential diagnosis includes DFSP and atypical fibroxanthoma.

Evaluation

Dermoscopic evaluation of dermatofibroma typically reveals a central white patch surrounded by a peripheral pigmented network. These lesions are reliably diagnosed through histopathological examination, complemented by the correlated clinical examination. When evaluated before biopsy using sonography, dermatofibromas should appear as avascular lesions within the dermis, often with superficial subcutis involvement and spiculated margins that are not well defined. The size and margins of these lesions typically correlate well on histopathological examination with sonographic findings.[21][22][23]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for dermatofibromas is generally unnecessary unless the lesion is causing symptoms. Excision for histopathological examination is indicated when the lesion shows signs of malignancy, such as changes in appearance or bleeding. Atypical variants are more prone to recurrence and, rarely, may metastasize. Therefore, complete excision with clear margins is recommended.[10] Patients considering excision for cosmetic reasons should be informed that the resulting scar may be more noticeable than the initial lesion, particularly on the lower extremities. Cryotherapy may serve as an alternative treatment option for lesions that protrude above the skin surface and become irritated due to repeated trauma.[24]

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating benign dermatofibromas from more advanced and aggressive neoplasms that may mimic their appearance is crucial.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: DFSP is a locally aggressive neoplasm of low-to-intermediate grade that can resemble a benign dermatofibroma. An early lesion of DFSP may manifest as an indurated skin-colored nodule that gradually enlarges over months to years. A histopathological examination is essential for accurate diagnosis, as several distinguishing features exist.

DFSP is characteristically more cellular and tends to involve a greater extent of the subcutis, often displaying a "honeycomb" entrapment of subcutaneous fat. Immunohistochemical staining can be particularly helpful in challenging cases, as DFSP typically stains positive for CD34 and negative for factor XIIIa. In contrast, benign dermatofibromas will stain strongly positive for factor XIIIa but negative for CD34. Additionally, dermatofibromas may exhibit higher positive staining for D2-40. Ki-67 staining should indicate a much higher proliferation index in DFSP, and the mitotic rate should also be significantly higher in DFSP compared to dermatofibroma.

Kaposi sarcoma: Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by spindled cell proliferation within the dermis and may be confused with the aneurysmal variant of dermatofibroma. Kaposi sarcoma typically exhibits red blood cells between spindled cellular areas and vascularity. However, Kaposi sarcoma should test positive for human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) and may also stain positive for CD31, CD34, and D2-40.

Intradermal nevi: Intradermal nevi typically have a softer consistency than dermatofibromas and do not exhibit dimpling upon pinching.

Keratoacanthomas: Keratoacanthomas are characterized by a rapid growth rate and often display a central keratinous plug.

Basal cell carcinomas: Basal cell carcinomas can resemble dermatofibromas, especially when they exhibit overlying follicular induction, characterized by epidermal hyperplasia such as basaloid proliferation. Differentiating between these lesions can be challenging, particularly in superficial biopsies that may miss the underlying dermatofibroma. A characteristic feature of basal cell carcinomas is that they exhibit peripheral palisading. However, important distinguishing factors include the presence of CK20-positive Merkel cells in follicular induction. Signs favoring dermatofibroma may include clear cell hyperplasia, the absence of nuclear atypia, and less crowding.[7][25][26][27]

Prognosis

Dermatofibromas are benign lesions with an excellent prognosis. Some lesions may even undergo spontaneous regression, resulting in hypopigmented skin. Most dermatofibromas remain stable for years without significant changes. With thorough excision, these lesions rarely recur, and only the most aggressive variants show local recurrence in approximately 20% of patients. Consequently, in excisional biopsies involving cellular or atypical variants, re-excision may be recommended to ensure clear margins due to the documented, albeit low, rate of local recurrence. Although extremely rare, metastases have been reported.[3][27][28]

Complications

Complications associated with dermatofibroma primarily arise from surgical removal and may include bleeding, infection, scarring or disfigurement, and the necessity for additional procedures.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed that dermatofibromas are benign entities and do not necessarily require excision. Although clinical history, histopathological examination, and imaging studies may suggest a dermatofibroma, a conclusive diagnosis can only be established through pathological examination. Moreover, patient preferences and desires are critical in the decision to excise these lesions versus opting for surveillance.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients should be informed that dermatofibromas are benign entities and do not necessarily require excision. Although clinical history, histopathological examination, and imaging studies may suggest a dermatofibroma, a definitive diagnosis can only be made following a pathological examination. Patients' preferences may also impact the decision to excise these lesions or opt for surveillance. If surveillance is chosen, any abrupt or unusual change in the behavior of any skin lesion should prompt a referral to a competent dermatologist for evaluation.