Introduction

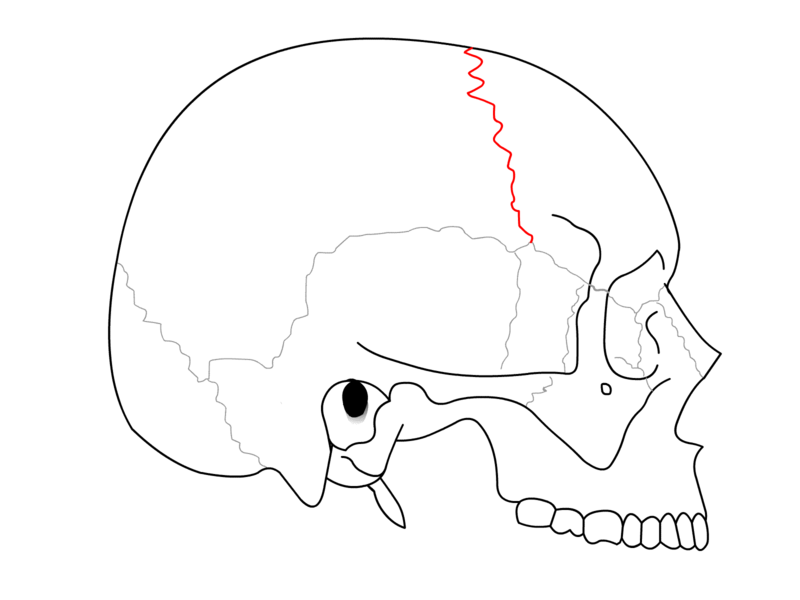

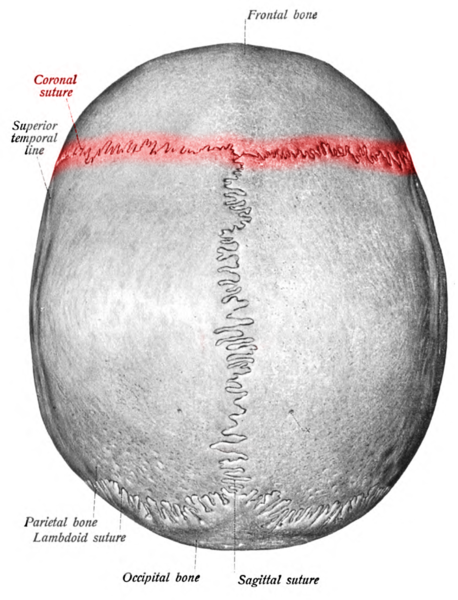

Cranial sutures are syndesmosis between the cranial bones. A syndesmosis is a fibrous joint between 2 bones. The coronal suture is oblique in direction and extends between the frontal and the parietal bones (see Image. Coronal Suture). The term is derived from the Latin word "corona" and the Ancient Greek word "korone," both translating to “garland” or “crown,” referring to the anatomical location where a crown would be placed. It is one of the four major skull sutures alongside the metopic (also known as a frontal suture), sagittal, and lambdoid sutures (see Image. Coronal Suture, Labeled).

The coronal suture extends cephalad (toward the apex of the skull) and meets the sagittal suture. This point is called the "bregma" and indicates the position of the anterior fontanel. The coronal suture extends caudal (toward the base of the skull) to the pterion. The pterion is the area where four bones, the parietal and frontal bones, the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, and the squamous part of the temporal approach each other. Several minor sutures, such as the sphenoparietal suture, sphenosquamous suture, and sphenofrontal suture, are at the pterion. The pterion is deemed the skull's weakest part.[1]