Continuing Education Activity

The Colles fracture is defined as a distal radius fracture with dorsal comminution, dorsal angulation, dorsal displacement, radial shortening, and an associated ulnar styloid fracture. The term Colles fracture is often used eponymously for distal fractures with dorsal angulation. These distal radius fractures are often caused by falling on an outstretched hand with the wrist in dorsiflexion, causing tension on the volar aspect of the wrist, causing the fracture to extend dorsally. Colles fractures require medical management to ensure proper healing. Colles fractures require multiple aspects of the healthcare team for each patient to allow for optimal care of each patient. This activity outlines the evaluation, treatment, and management of Colles fractures and explains the interprofessional team's role in caring for this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of Colles fractures.

- Outline the appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of a patient with a Colles fracture.

- Review the treatment and management options available for Colles fractures.

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance Colles fracture management to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Named after Abraham Colles, who first described a distal radius fracture in 1814 at the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin, the Colles fracture is one of the most common fractures encountered in orthopedic practice representing 17.5 % (one-sixth) of all adult fractures presenting to the emergency department.[1][2] The Colles fracture is defined as a distal radius fracture with dorsal comminution, dorsal angulation, dorsal displacement, radial shortening, and an associated ulnar styloid fracture.[3][4] The term Colles fracture is often used eponymously for distal fractures with dorsal angulation.[5] These distal radius fractures are often caused by falling on an outstretched hand with the wrist in dorsiflexion, causing tension on the volar aspect of the wrist, causing the fracture to extend dorsally.

Anatomy

The distal radius bears 80% of the axial load. It has the following articulations; scaphoid ( scaphoid fossa), lunate ( lunate fossa), and distal ulna ( ulnar or sigmoid notch).

The distal radius has three columns; radial, intermediate and ulnar columns.

The radial column ( radial styloid + scaphoid fossa):

- It has the attachment of the brachioradialis tendon, long radiolunate ligament, and radioscaphocapitate ligament, which prevents ulnar translation of the carpus.

- It works as a buttress for radial translation of the carpus and holds it to length radially for even load distribution across the scaphoid and lunate fossae.

- It acts as a load-bearing strut for wrist ulnar deviation.

The intermediate column (Lunate fossa): is responsible for load transmission from the carpus to the forearm.

The ulnar column ( TFCC + Distal ulna): Stabilizes the DRUJ and forearm rotation.

Etiology

The Colles fracture is most commonly caused by a fall, landing on an outstretched hand with the wrist in dorsiflexion. This condition is also known as a "fall on outstretched hand injury," referred to by the acronym "FOOSH injury." The severity of the injury is usually determined by the position of the wrist when injured as well as the amount of force of the trauma. Tension on the volar aspect of the wrist causes bending and compressive forces. As a result of these forces through the wrist, dorsal displacement and comminution occur.

Epidemiology

Distal radius fractures occur in people of all ages and, more often, in females. Distal radius fracture has a bimodal distribution in young athletes from high-energy injuries, as in sporting activities and motor vehicle accidents, and the elderly from low-energy trauma. In pediatrics, fractures often occur around the time of puberty due to low bone mineralization. Interestingly, ages 19 to 49 years old make up the least common age group for these injuries.[6]

Osteoporosis associated with aging increases the risk of these fractures in elderly individuals and also increases the risk in women, who are more commonly affected by osteoporosis.[7] Osteoporosis is a predictor of subsequent fragility fractures, especially in women older than 50 years old. Ideally, a distal radius fracture in women older than 50 years of age should indicate a DEXA scan to assess bone quality.

Pathophysiology

The most common cause of Colles fractures is trauma. This usually relates to athletic injuries or motor vehicle accidents in younger patients. In the elderly population, this is most often caused by falls. When the traumatic force hits an outstretched hand, force is transmitted dorsally through the wrist, fracturing the distal radius, displacing it dorsally, and often causing dorsal comminution. This mechanism leads to the classic “dinner fork” deformity of the wrist with associated pain, edema, and decreased range of motion.[8]

Distal radius fracture can be associated with multiple other injuries, such as distal radioulnar joint injury (DRUJ), Triangular fibrocartilage injury (TFCC), scapholunate, and lunotriquetral ligament injuries. An associated radial styloid fracture would indicate a high-energy mechanism of injury.

History and Physical

In distal radius fractures, thorough physical exams of the affected and nonaffected extremities are important in diagnosing and managing the injury. Wrist pain and tenderness to palpation will present on the exam. A classic dorsiflexion deformity is often seen when the fracture is displaced and is also known as a “dinner fork” deformity. Bruising and swelling may also be visible, and a thorough skin exam is necessary to evaluate for a possible open fracture. The range of motion may be decreased due to the injury but should be assessed by the clinician if possible. Assessment of the neurovascular status of the extremity distal to the injury is paramount, including a full exam of pulses, sensation, and motor function of the affected extremity. Finally, joints above and below the injury always need to be assessed to evaluate for other associated injuries.

Evaluation

Radiographs are usually the mainstay of evaluating, diagnosing, and initially managing these injuries. PA and lateral views should be taken at a minimum to assess these injuries. These radiographs help distinguish the type of injury among different types of forearm fractures to narrow down and make a diagnosis.[9] (Media 4 & 5 ) for AP and lateral radiographs of a typical Colle's fracture,

The following radiographic parameters should be considered when assessing a wrist radiograph.

In the posteroanterior view (PA):

Radial height: Normally 13 mm. A shortening of < 5 mm is acceptable. (Media 6)

Radial inclination: Normally 23 degrees. A change of < 5 degrees is acceptable. (Media 7)

Articular step-off: The articular surface should be congruous. A step off < 2 mm is acceptable.

In the lateral radiographs:

Radial volar tilt: Normally is 11 degrees. A dorsal angulation < 5 degrees or within 20 degrees of the contralateral side is acceptable. (Media 8)

CT scan is mainly indicated to delineate an intraarticular fracture pattern and for surgical planning.

MRI is not a recommended diagnostic measure as the initial evaluation; however, it may serve to assess ligamentous or soft tissue extents of these injuries, such as TFCC, scapholunate, or lunotriquetral ligament injuries.

Treatment / Management

Distal radius fractures can be managed either non-operatively or operatively, depending on the fracture pattern and the patient profile.

Non-operative Management

Closed reduction and immobilization with either splint or cast: This is indicated in extraarticular fracture with acceptable shortening (< 5 mm) and dorsal angulation ( < 5 degrees or within 20 degrees of the contralateral side). See (Media 9) showing successful closed reduction and casting of a Colle's fracture.

Closed manipulation/reduction requires adequate anesthesia: Usually performed in the emergency department in the form of a hematoma block or a Bier's block. The reduction is performed by inline traction and dorsal pressure of the distal fracture fragment. A three-pointed molded plaster is applied. Care should be taken to avoid plastering in excessive flexion or ulnar deviation (Cotton-Loder Position), which could precipitate carpal tunnel syndrome. The patient should be followed up in one week with radiographs of the involved wrist to check that the reduced position is maintained. Plaster is usually removed after a total of six weeks. Home exercises yield the same outcomes as physical therapy for simple distal radius fractures.[10] Closed treatment could be complicated by acute carpal tunnel syndrome or EPL rupture.

LaFontaine defined predictors of instability, where a fracture pattern with three or more of the following criteria would have a high chance for loss of reduction.[11]

The most predictive criteria are radial shortening followed by dorsal comminution.

Initial fracture pattern (Pre-reduction) with the following criteria:

Radial shortening > 5 mm, dorsal comminution > 50%, volar or intraarticular comminution. Dorsal angulation > 20 degrees. Displaced intra-articular fractures > 2mm.

Other criteria include severe osteoporosis or associated ulnar fracture.

In the elderly population (> 65 years), there is no difference in functional outcomes between non-operative versus operative treatments.

Operative Management

Closed Reduction and Percutaneous Pinning (CRPP):

- Indicated for extraarticular distal radius fractures. It has up to 90% success results when performed satisfactorily for the correct fracture pattern.

- The K wires can be used as a reduction tool by inserting them dorsally into the fracture from distal to proximal (Kapandji intrafocal technique)[12][13]

- Alternatively, an arthroscopically assisted reduction can be performed (Rayhack technique)[14]

- Percutaneous pinning could be complicated by injury to the superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve or pin tract infection[4]

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF)

- Indicated for unstable fracture patterns ( Judged in the prereduction radiographs as per LaFontaine criteria)[15]

- Progressive loss of reduction following closed attempt ( Loss of volar tilt and radial height)

Other unstable distal radius fractures where ORIF is indicated include:

- Articular margin fractures ( dorsal or volar Barton's fractures)

- Die Punch fracture

- Displaced comminuted extraarticular fractures (Smith's fractures)

NB. The critical corner: This is the volar ulnar corner that supports the lunate fossa ( through radiolunate ligament attachments). This must be addressed when operative management is indicated as missing, which can result in volar carpal subluxation with subsequent fixation failure.[16]

ORIF with plating can be performed via volar or dorsal approaches. Volar plating is preferable to dorsal plating. Dorsal plating should be used when appropriately indicated, such as in cases of dorsal comminution, angulation, and associated carpal pathology.[17]

Volar Plating [18]

Advantages: New volar locking plates show improved support of the subchondral bone.

Disadvantages:

- Irritation of both flexor and extensor tendons.

- Plates positioned distal to the watershed area are associated with FPL rupture.

- Injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve with resultant hyperesthesia over the thenar eminence base. (a result of retraction of flexor tendons during plating)

Plating can be performed alone or in combination with external fixation or K-wire fixation. Bone grafts may be indicated in bone loss from significant comminution. The critical corner (lunate fossa fragment) should be assessed and addressed when indicated, and it might need fragment-specific fixation.

Complications (overall complication rate close to 15% with less than 5% requiring reoperation).[19]

- Tendon rupture.

- Screw penetration into the wrist joint or distal radioulnar joint.

- The final screws' position should be assessed with 20 degrees elevated lateral views.

- The dorsal cortex should be assessed with a skyline view.

Rehabilitation with home exercises is not inferior to therapist-directed physiotherapy.[20][10]

External fixation (spanning or non-spanning): indicated for open fractures, comminuted fractures not amenable to internal fixation, and patients unfit for long procedures.[21][22][23][24]

- Spanning external fixation is for fractures with a small articular fragment, while non-spanning is for fractures with a large articular fragment.

- External fixation is usually used as an adjunct measure to other fixation methods, e.g., plate or wire fixation.

- It works through ligamentotaxis to restore radial length, but alone it can not reliably restore volar tilt.

- Carpal distraction should be less than 5 mm in the neutral position.

Complications

- Pin tract complications (infection, fracture through pin site)

- Malunion & non-union

- Stiffness and weak hand grip power

- Neurologic injury ( superficial sensory branch of the radial nerve, median neuropathy, or reflex sympathetic dystrophy)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for Colles fractures includes other types of distal radius fractures, as well as other forearm fractures, each of which can be differentiated with radiographic imaging.

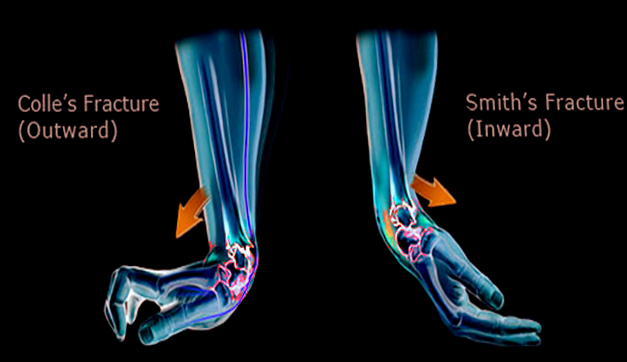

Smith fracture: Often referred to as a “reverse Colles,” the Smith fracture involves volar (rather than dorsal) angulation of the distal radial fragment and is usually caused by a FOOSH in supination rather than in pronation.

Barton fracture: A Barton fracture is another type of distal radius fracture that involves the dorsal rim of the distal radius, in which an oblique intra-articular fracture occurs.

Hutchinson or Chauffer fracture: Intra-articular radial styloid fractures are also known as Hutchinson or Chauffer fractures and usually present as oblique or transverse fractures to the radial styloid caused by direct trauma.

Galeazzi fracture: Fracture of the medial or distal radius with associated dislocations of the distal radioulnar joint.[25]

Monteggia fracture: Ulnar shaft fracture with associated radial head dislocation.[26]

Essex Lopresti lesion: This is a rare combination of Galeazzi and Monteggia fractures involving a radial head fracture at the elbow with associated DRUJ disruption at the wrist and interosseous membrane disruption throughout the forearm.

Prognosis

The prognosis of a Colles fracture depends on the severity of the injury and the extent of any complications that arise from the injury. Complications are avoidable through prompt and adequate reduction followed by splinting, casting, and follow-up with an orthopedist. Severe injuries such as an open fracture or injury with neurovascular compromise or evidence of compartment syndrome require urgent orthopedic consultation. Severe injuries often need surgical repair. Prognosis also depends on patient age, as younger patients have excellent potential for bone remodeling, while elderly patients are less likely to have such positive outcomes.[27]

Complications

Complications of Colles fractures can be classified as early and late and can range from mild effects to significant long-term disability. Early complications include compartment syndrome, median nerve injury, and vascular injury. Less acute and long-term complications include carpal tunnel syndrome and osteoarthritis. Malunion can occur when successful reduction does not hold. It can result in tendon injury and lead to chronic wrist pain.[28]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with wrist injuries concerning fractures should seek immediate medical attention. Colles fractures are one of the most common wrist injuries made up of distal radius fractures with dorsal displacement. These injuries need prompt reduction, followed by splinting and casting with follow-up by an orthopedist to ensure proper healing. Severe injuries may require surgical repair. Patients need to be aware of the appropriate splint and cast management, involving the adequate assessment of neurovascular status. If a cast is too tight, causing severe pain, numbness or tingling of the fingers, or discoloration of the digits, immediate medical attention is warranted. The anatomy is restorable with proper treatment, management, and follow-up of these injuries, and good functional outcomes are achieved.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with Colles fractures frequently present for medical attention and require a complete interprofessional team for comprehensive and optimal management. For example, patients who present to an emergency department interact with various medical personnel to get the required care. The orthopedic surgeon will often be the final destination for these patients, as this is often the optimal treatment to correct the injury; however, they are usually not the patient's point of initial contact.[29] Patients will initially present to emergency departments, urgent care centers, or physician outpatient offices, where they will interact with intake triage nurses. The patient will then interact with patient care nursing staff, radiology technicians for imaging, possibly laboratory technicians if lab work is needed, and emergency physicians or another clinician in the office they have visited for treatment.

The treatment team will often work together with radiologists reading the images to make the diagnosis. Orthopedic surgeons are usually contacted for treatment options following a confirmed diagnosis, as surgery is often necessary for definitive management depending on the severity of the injury. Communication among all aspects of the healthcare team is essential in ensuring prompt and proper care for the patient. Physical and occupational therapists may have involvement after the removal of the cast. Orthopedic nurses will often assume the role of care coordinator, managing the contacts between PT, and the surgeon, any potential pharmacy involvement for pain control at the initial injury, and assisting with reduction and surgery. These interprofessional measures can drive better outcomes for patients with a Colles fracture [Level 5]