Continuing Education Activity

A cleft palate is a common congenital craniofacial condition characterized by an opening or split in the roof of the mouth due to incomplete tissue fusion during fetal development. This condition can affect infants' feeding and breathing and children's speech, as the anomaly impairs the separation between the nasal and oral cavities. Infants with a cleft palate often struggle with nasal reflux, forming a secure latch for feeding, and may tire easily during feeding due to increased effort.

A cleft palate can occur in isolation or as part of a syndrome and can be detected prenatally using advanced imaging techniques. Treatment typically involves an interprofessional approach, including early intervention for feeding challenges and long-term support for speech and hearing. Surgical repair usually occurs within the first year of life, aiming to restore normal function by closing the cleft and enhancing speech and swallowing abilities. This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner's competence in recognizing the significance and clinical features of cleft palate, performing the recommended evaluation, and implementing an appropriate interprofessional management approach to improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

Assess the clinical features of cleft palate.

Determine the appropriate evaluation of cleft palate.

Identify the various management options available for cleft palate.

Apply interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and outcomes in patients with cleft palate.

Introduction

Cleft lip and palate, one of the most common congenital craniofacial abnormalities, is characterized by failure of normal fusion of the palate and lip during development, resulting in a clinically evident discontinuity of the lip or palate at birth. Cleft lip and palate (CL/P) and cleft palate alone (CPO) are not only cosmetic deformities but have significant functional morbidity for the newborn without adequate management. CL/P impacts the newborn's ability to feed in multiple ways, including increased nasal reflux, inability to form an adequate latch, and increased work of feeding, leading to fatigue.

Furthermore, while CL/P and CPO frequently occur in isolation, in up to 30% of cases, these defects can also be part of a congenital syndrome, which must be recognized to initiate early interprofessional management.[1] This resource primarily discusses an overview of cleft palate. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Cleft Palate Repair," "Cleft Lip," and "Cleft Lip Repair," for more detailed information.

Etiology

Abnormal Embryological Development of the Palate

Cleft palate arises from abnormal development of the palate or surrounding structures during gestation. Embryologic development of the palate is an extraordinarily complex sequence of events involving cell migration, cell differentiation, and apoptosis. The primordial facial structures originate from neural crest cells very early in embryogenesis. These then undergo a transformation to epithelial-mesenchymal cells and migrate to the proto-craniofacial area, where they are joined by ectodermal and mesoderm cells, combining to form the branchial arches and the facial processes.[2][3] This process begins in gestational week 4, wherein the following 5 facial prominences surround the developing mouth and oral cavity:

- Frontonasal prominence in the median

- Bilateral maxillary prominences laterally

- Bilateral mandibular prominences laterally and inferiorly

By week 5 of embryogenesis, the frontonasal prominence develops into medial and lateral nasal processes via a cleavage. These medial and lateral nasal processes then fuse with the maxillary process to form the upper lip. The medial nasal processes then fuse in the midline to form the intermaxillary segment, which forms the philtrum of the upper lip and the primary palate (ie, the portion of the palate anterior to the incisive foramen) in gestational week 6.[4] The lateral nasal processes will go on to form the nasal alae. The mandibular processes fuse in the midline to form the lower lip and mandible, while the lateral fusion of the mandibular and maxillary processes forms the oral commissures. Failure, disruption, or interruption of any of these fusion points can result in clefting.

This embryologically explains why a cleft lip resulting from the failure of fusion of the nasal and maxillary processes is also commonly associated with a cleft of the primary palate, as these structures are formed by the same stage in embryological development. A failure of other embryological fusion events can result in various atypical facial clefts. For example, the failure of lateral fusion of the maxillary and mandibular processes yields the Tessier 7 cleft.[5] Gestational weeks 4 through 6 are crucial for craniofacial development, and teratogenic events during these weeks are more likely to result in cleft facial abnormalities.[6] Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Mandibulofacial Dysostosis" and "Embryology, Face," for further information on other facial abnormalities.

The secondary palate forms from initial outgrowths of the maxillary processes, the palatal shelves. These structures are initially oriented vertically, posterior to the primary palate, and lateral to the developing tongue. These shelves begin to orient themselves horizontally in gestational week 8 and progress towards midline fusion, beginning anteriorly, immediately behind the primary palate, with midline fusion progressing posteriorly in a "zipper" fashion.[4]

As the palatal shelves extend toward one another in the midline, the medial edge epithelium makes a point of contact. These then fuse into a midline epithelial seam, subsequently degenerating into mesenchymal tissue, establishing mesenchymal continuity of the full palate. Failure of midline fusion results in cleft palate.[7] This mesenchymal tissue then differentiates into bone in the hard palate and soft tissue in the soft palate.[8]

Congenital Syndromes Associated with Cleft Palet

CL/P and CPO are found in over 200 different congenital syndromes. The most commonly discussed are CHARGE (coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, growth retardation, genital abnormalities, and ear abnormalities) syndrome and velocardiofacial or DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion). Approximately 50% of CPO cases are associated with other congenital anomalies, more frequent than CL/P, which is associated with a congenital syndrome in about 15% of cases. The congenital abnormalities most commonly associated with CPO are the Pierre Robin sequence of micrognathia or retrognathia, glossoptosis, and cleft palate. This sequence of anomalies is most commonly seen in Stickler syndrome but is also found with Treacher Collins, Nager, DiGeorge, and fetal alcohol syndromes.[7][9][10]

Molecular and Environmental Factors Associated with Cleft Palet

Significant heterogeneity exists in the molecular pathways associated with the development of CL/P and CPO. The pathways associated with the formation of the lip and palate include the sonic hedgehog pathway (SHH and SPRY2 genes), which interacts closely with the bone morphogenic pathway (BMP4 and BMP2 genes), fibroblast growth factor pathways (FGF10 and FGF7 genes), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ) receptors and ligands. Disruption of these pathways at various stages results in varying severity, laterality, and location of clefts.[9][11]

Furthermore, studies have shown a clear environmental impact on the development of CL/P and CPO. Risk factors for malformation include smoking, diabetes, gestational diabetes, and teratogen exposure (eg, valproic acid, phenytoin, retinoic acid, dioxin, and thalidomide). A clear familial association between CL/P and CPO is present, as clefts in parents and siblings also increase the risk that a subsequent child will be affected. A child of an affected parent has a 3% to 4% risk of CL/P and about 6% of CPO. For parents with 1 affected child, the risk of another affected child is 4%, and with 2 affected children, 9% for CL/P and 2% and 1%, respectively, for CPO. The risk of either increases from 14% to 17% if both a parent and a child have a type of cleft.[7][9][10]

Epidemiology

CL/P is the most common craniofacial defect in the newborn and the fourth most common overall congenital anomaly. The literature quotes a prevalence of anywhere from 1 per 650 to 1000 live births; Asian patients are affected twice as commonly as White patients. Males are 2 times more commonly affected than females.

A global study by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, including over 7.5 million births, found a prevalence of CL/P of 6.64 per 10,000 births, including stillbirths and terminations. For cleft palate alone, the prevalence was 3.28 per 10,000. Of these, 77% were isolated, 16% had other malformations, and 7% had a recognized syndrome.[7][10][12][13]

Pathophysiology

The palate serves numerous essential functions, but the physical separation of the nasal and oral cavities is the most fundamental. A cleft palate creates a persistent communication between these 2 spaces, with deleterious effects on speech, swallowing, and breathing, particularly in neonates. A cleft palate leads to unwanted air escape during speech, preventing the proper formation of plosive sounds and leading to hyponasal speech.[14] If unrepaired, this can lead to lifelong errors in speech development that can be challenging to overcome with speech therapy.

In the immediate postpartum period, neonates are obligate nasal breathers. The abnormal communication between the mouth and nose can lead to the tongue protruding into the nasal cavity and interrupting normal nasal breathing. In addition to hampering the ability of the infant to latch onto a nipple, a cleft palate can interfere with primary feeding and the suck-swallow-breathe coordination necessary for maintaining nutrition.[15] Long-term effects can also include dental malposition, abnormal facial growth, and catastrophic psychosocial effects due to stigmata associated with cleft speech and nasal regurgitation of food.[16][17]

History and Physical

In many cases, prenatal diagnosis can be made via ultrasonography around 18 weeks gestation, though this is highly dependent on technician experience and skill. With traditional 2-dimensional ultrasonography, a cleft lip is more accurately detected than a cleft palate. A significant advancement in diagnosing cleft palate has evolved with 3-dimensional ultrasonography, which has 100% sensitivity in detecting cleft palate in a fetus that has already been diagnosed with cleft lip.

Prenatal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for further characterization of the cleft and is used when a CL/P has already been identified to evaluate for other defects, especially if a potential for additional intracranial findings in the setting of a known or suspected genetic syndrome is present. Prenatal identification allows for parental counseling and earlier intervention.[10][18]

Antenatally Diagnosed Cleft Palate

If the cleft palate is diagnosed via prenatal ultrasonography, the family will often be referred for a prenatal visit with an interprofessional cleft team.[19] Essential aspects of the history at this visit include a thorough family history for both biological parents, if known and available, focusing on any family history of clefting or other genetic syndromes. A prenatal history should be obtained, including details of obstetrical care and any genetic screening undertaken. A social history, including tobacco, alcohol, recreational drug use, and environmental exposures, should also be obtained. A maternal medical history should also be obtained, including any medications taken during pregnancy. Evaluation by a medical geneticist is a standard part of many cleft teams, but a referral may be made if additional factors are elucidated from this prenatal visit.

After the child is born, the family will meet again with the cleft team, with the precise timing of this initial visit determined by the type of cleft, any additional medical or syndromic needs, and how the child progresses in the immediate postnatal period in terms of breathing, feeding, sleeping, and growth.[20] If any medical team member has concerns about these parameters, the child should be seen as soon as possible to facilitate early intervention. This first visit will focus on the parameters potentially affected by the cleft.

Ensuring the child is breathing and sleeping comfortably is paramount, and obtaining a sleep and feeding history and growth curves form the basis of this assessment. If the child is breathing normally and maintaining their growth curve, then close observation may be all that is warranted at this early time. Physical examination should assess the child at rest, looking for increased work of breathing sitting, supine, and feeding, and a detailed physical examination should be undertaken.

A thorough head and neck examination should be performed to examine for abnormal facies or ocular abnormalities, and an otologic examination should be performed to determine the presence of middle ear fluid; newborn hearing screening results should also be noted. Oral examination should note the type of cleft (lip, palate, or both), whether unilateral, bilateral, or atypical, and whether the cleft involves the primary palate, secondary palate, or both. The size and position of the mandible and alveolar arches should be noted, and cardiopulmonary and extremity examinations should be performed to evaluate for other abnormalities.[21] If a genetic syndrome is suspected based on family history or this initial examination, further testing may be indicated, such as an echocardiogram or renal ultrasound.[2]

Postnatally Diagnosed Cleft Palate

In this case, the first visit and subsequent history and physical examination essentially combine the 2 visits described above. A thorough family and prenatal history must be obtained, together with a thorough physical examination and recent developmental history of the child. Referrals may be required for genetic evaluation, audiometry, other specialty workup, and referral to an interprofessional cleft team.[19]

Submucous Cleft Palate

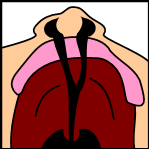

A submucous cleft palate is the mildest form of cleft palate and can take many shapes. The most minimal, and often asymptomatic, is the bifid uvula. Whenever this finding is encountered clinically, a thorough oral examination, both visual and bimanual, should be undertaken. A posterior palatal notch may be palpated, and a zona pellucida (see Image. Submucous Cleft Palate) may be visible in a submucous cleft; either finding may be present without a bifid uvula.[22]

The zona pellucida represents the incomplete fusion of the palatal sling muscles in the midline in the presence of complete fusion of both the nasal and oral mucosal layers. The palatal sling is thus incomplete, and the patient is at risk for eustachian tube dysfunction and weakened palatal closure of the nasopharynx.[23] A thorough speech examination and nasal endoscopy are warranted; mirror-fogging testing is also useful at the bedside for trace air escape and velopharyngeal insufficiency if the patient is intolerant of formal nasal endoscopy. Great care should be taken when considering adenoidectomy.[24] A thorough feeding history is also essential, as trace nasal regurgitation is not uncommon.[25] Without clinically significant velopharyngeal dysfunction and otologic disease, many submucus cleft palates simply warrant observation. Still, ongoing observation is vital through puberty, as symptoms can develop, and late diagnosis is common.[26]

Evaluation

After birth, neonates with CL/P will require evaluation and care from an interprofessional healthcare team. The initial assessment is focused on respiratory and feeding issues to ensure the infant can grow and develop appropriately until the definitive surgical repair. Neonates need to be evaluated for sleep apnea, and parents counseled on appropriate management.

A trained speech therapist must work with parents to teach appropriate feeding techniques and provide assistive devices to improve intake and reduce infant fatigue during feeds. Various special bottles and nipples are available to protect the nasal passages from reflux during feeds, decrease respiratory distress while feeding, and ensure adequate caloric intake. Many of these require practice for the caregiver feeding the infant and instruction with a specialized speech therapist or lactation consultant. Infants with clefts may nurse more efficiently from a breast than a bottle.[27]

A dental and orthodontic evaluation should also be considered for possible oral prosthetics to aid feeding until surgery or to evaluate for nasoalveolar molding (NAM) if a cleft lip is also present.[28] Appropriate infant weight gain is essential for development and preventing surgical intervention delays. Subsequent and long-term evaluations include:

- Audiologic assessment

- Evaluation with a newborn hearing screening is essential if it is available. Even if the infant has passed this, subsequent audiometry and tympanometry are required to evaluate for eustachian tube dysfunction and potentially correctable conductive hearing loss.

- If the child fails the newborn hearing screen and cannot be evaluated with age-appropriate audiometry, an auditory brainstem response is indicated to confirm the continuity of the neural pathways for hearing.[29] This should be completed in the first months of life to ensure early hearing restoration if indicated.

- Speech-language assessment

- Assessment of feeding and language development is also recommended.

- Functional assessment should begin in the prelingual years, focusing on feeding but continuing into the school years as the patient adapts to speaking and swallowing with surgically corrected anatomy.

- Dental evaluation

- The first evaluations should occur as primary teeth erupt and continue as permanent dentition erupts from early childhood through adolescence.

- Dental misalignment is common, as are missing or misshapen teeth if an alveolar cleft is present. The need for braces and possibly orthognathic surgery in the teen and adult years is also high.[30]

- Psychosocial and genetic counseling

- Counseling is recommended for both parents and child

- For parents, this can form an important part of the early interprofessional team visits and can occur prenatally.

- Mental health resources should always be available to children as they progress through the school years to cope with any challenges associated with the social stigma of a cleft.

- Family genetic counseling should be offered in addition to future planning as patients with a cleft palate enter adulthood and consider children of their own.[7][31]

Treatment / Management

Definitive management of cleft palate is achieved through surgical intervention, with the overall goal of separating the nasal cavity from the oral cavity and providing a palate with enough length to prevent velopharyngeal insufficiency and potentially restore eustachian tube dilator function to the palatal sling muscles. No single surgical technique is preferred to accomplish these goals, and an astute cleft surgeon will master as many as possible to tailor the surgical intervention to each specific patient. Precise timing can vary from country to country and cleft center to cleft center, but several common goals guide treatment.

If a concurrent cleft lip is present, the lip is managed first, typically when the child is at least 3 months old. However, if severe feeding concerns are identified and thought to be curable with lip repair, an earlier repair may be undertaken. The age threshold of 3 months was chosen rather than a younger age as the cardiac risk associated with general anesthesia decreases significantly after gestational week 60.[32] Beyond this, the timing of the first surgical intervention is based on the often-quoted rule of 10, "10 pounds, hemoglobin of 10, and age older than 10 weeks." [33] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cleft Palate Repair," for more detailed information on surgical cleft palate repair.

Palatoplasty for cleft palate associated with cleft lip and for cleft palate alone is performed later, most commonly between 9 to 15 months of age, with individual centers preferring different intervention ages. The earlier the palate is repaired, the higher the incidence of midfacial growth abnormalities and the risk of a foreshortened palate as the child enters puberty. Some centers will repair only the soft palate at an early age, leaving the primary and remaining hard palate unrepaired until later in an attempt to provide some feeding benefit, but narrow the hard palate cleft and minimize facial growth disturbances associated with early palatoplasty.[34] Early palatoplasty (eg, at 10 to 11 months of age) has significantly improved speech development outcomes when compared to partial palate repair or delayed or 2-stage palate repairs that do not use interval obturation, all of which are associated with a higher rate of speech delay and need for speech therapy services in the school-aged years.[35][36]

Preoperatively, for a CL/P, the lip is usually taped from about 1 week of life until surgery. This pseudo-recreation of the orbicularis oris helps narrow the cleft segments and improve overall symmetry; some centers will perform a surgical lip adhesion to achieve this function in preparation for later definitive palatoplasty.[37] NAM is an alternative and more aggressive measure to lip taping, which can lead to an improved cosmetic and functional outcome after surgery. NAM involves the placement of a prosthesis that is fitted from a maxillary impression and is worn 24 hours a day and adjusted weekly or biweekly. NAM can result in far improved nasal symmetry and alveolar alignment. However, it is a significant time and effort commitment for families, and poor compliance can significantly impact outcomes. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Cleft Palate Repair" and "Cleft Lip Repair," for more detailed information on 2-stage lip repair and surgical cleft lip repair.[10][38]

Palatoplasty Techniques

The most critical step in any palatoplasty technique is the separation of the nasal and oral cavity to maximize normal speech and swallowing. Most palatoplasty techniques employ a multilayered closure to minimize the rate of postoperative fistula and address the reconstruction of the levator veli palatini muscle, which elevates the palate during speech and swallowing.[39] Palatoplasty must be tailored to the type of cleft present, including unilateral versus bilateral and complete (involving both the primary and secondary palate) versus incomplete, and may involve multiple procedures. Each repair technique has unique advantages and disadvantages; the method selected depends on the operating surgeon's preference and clinical factors.

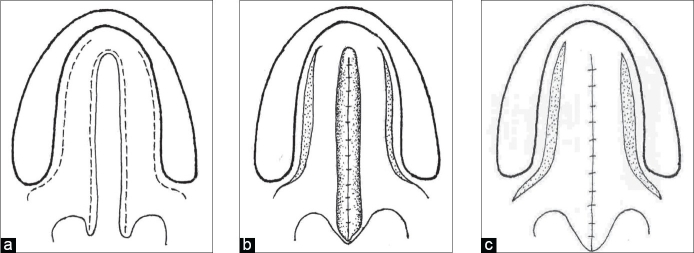

Straight-line repair and variations

Straight-line repair is perhaps the simplest technique to conceptualize and is amongst the oldest recorded. The first repair documented in modern literature was by le Monnier in 1764, which involved roughening the free palate edges and suturing them together in a straight line. This procedure was complicated by wound dehiscence and difficult access, particularly in the preanaesthetic era.[40] Roux described the first successful straight-line closure in this manner in 1819.[41] While the separation of, and individual repair of, nasal and oral mucosal layers in cleft repair was first described by von Graefe in 1816, it was not successfully performed until 1820.

This was followed by a straight-line, multilayer technique for hard palate repair by Dieffenbach in 1828.[42][43] This straight-line, multilayer technique involves the elevation of mucoperiosteal flaps off the vomer on either side of the cleft, accessed through the cleft. Nasal and oral mucosal flaps are anteriorly elevated from the maxillary alveolus toward the soft palate. The nasal-layer flaps are then rotated medially and closed in a layered fashion. Mucoperiosteal flaps are then raised off of the palatal shelves in the oral layer, taking care to preserve the blood supply from the palatine vessels. Often, the entire hard palate is elevated, and then this layer is closed in the midline.

The soft palate portion involves elevating the nasal mucosal surface off of the palatal sling muscles, which in the modern era are detached from their aberrant insertions into the posterior hard palate and reapproximated to form a palatal sling, and then the oral mucosal layer is closed as a distinct layer (see Image. Von Langenbeck Palatoplasty Diagram).[44] This basic, multilayered, straight-line closure was adopted in 1859 by von Langenbeck, who described lateral relaxing incisions, essentially creating pedicled flaps of both oral palatal mucosal layers. The von Langenbeck technique significantly decreased failure and fistula rate by decreasing tension on the surgical closure and allowed the repair of much wider palatal clefts.[45] The von Langenbeck technique is still employed today, particularly in the NAM setting where clefts may be narrow. This technique does not lengthen the palate and is most useful when the soft palate already makes adequate contact with the posterior pharynx.

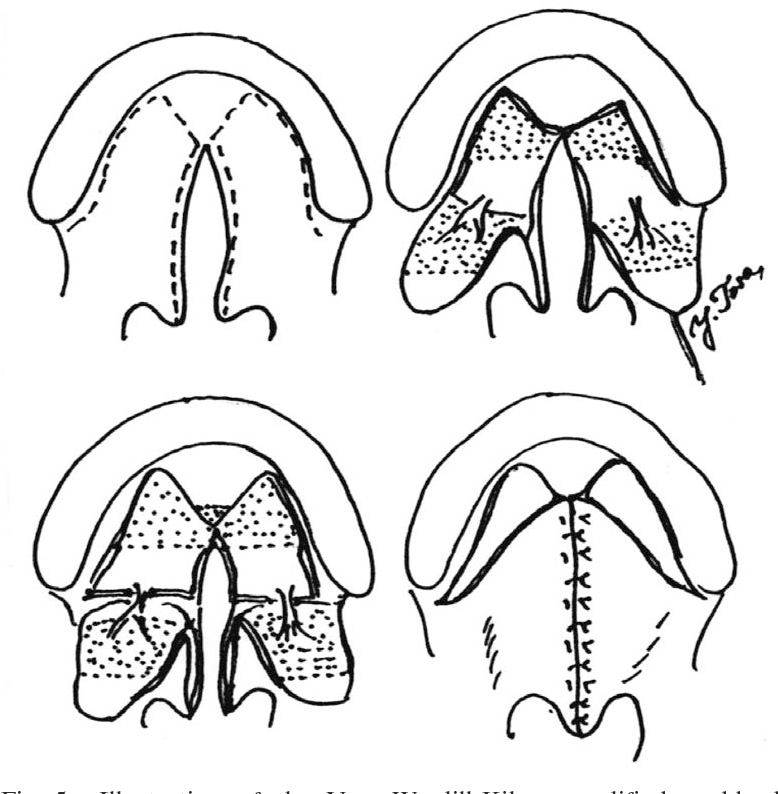

V to Y pushback closure

Further refinements of the multilayer, straight-line closure occurred between 1931 and 1937 independently by Veau, Wardill, and Kilner, who modified the anterior hard palate closure into a V to Y technique.[46] This technique involves the elevation of bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps involving oral mucosa in an anterior-to-posterior direction. The posterior attachments of the flaps remain intact and in continuity with the elevated palatal shelves in the oral layer. The mucoperiosteal flaps are then retroposed or pushed back and reapproximated at the midline in the same fashion as a V to Y closure, which allows for palatal lengthening, a significant shortcoming of the von Langenbeck technique (see Image. Veau-Wardill-Kilner V to Y Pushback Palatoplasty). The nasal mucosal layer is closed primarily in its position and is thereby exposed on its inferior or oral aspect to close by secondary intent. This technique is also still used in the modern age with narrow clefts and a moderately foreshortened palate.[47]

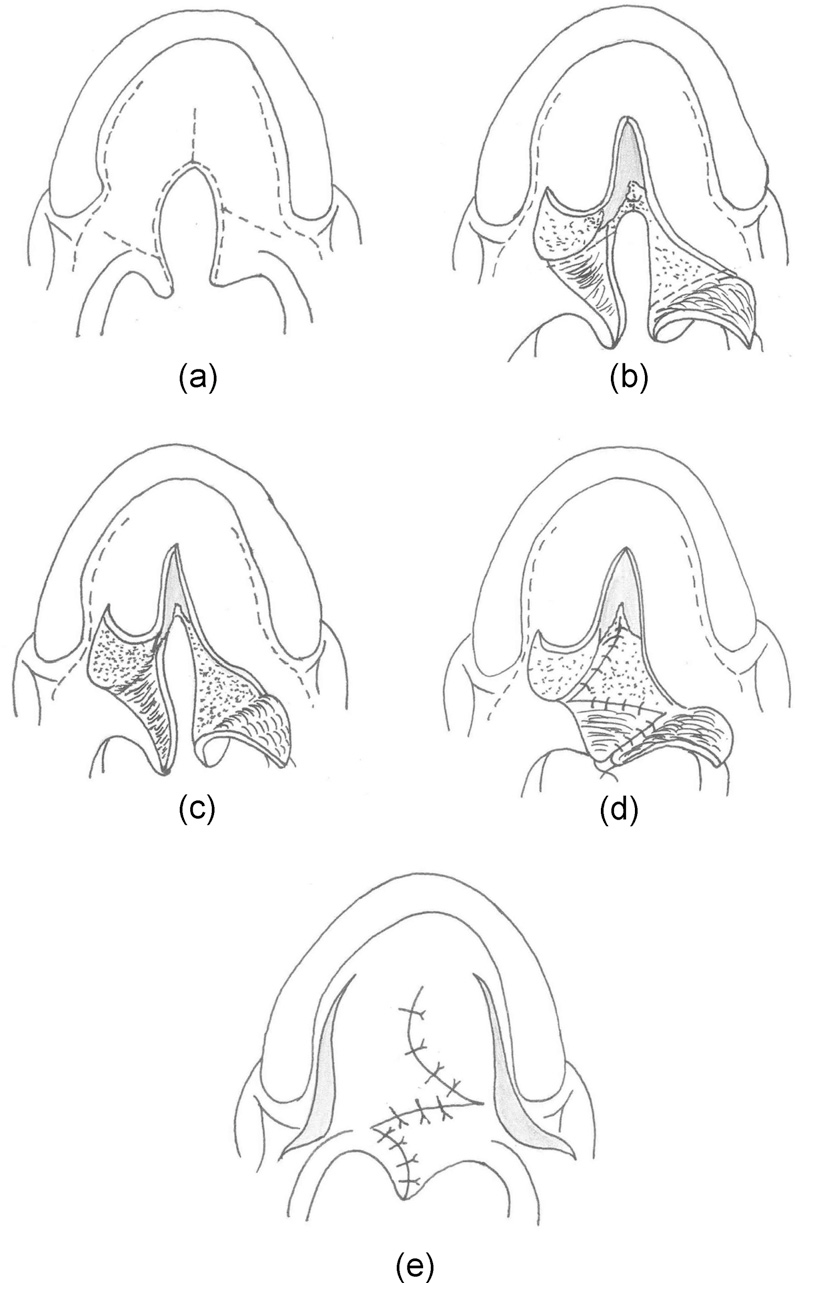

Furlow palatoplasty

The Furlow palatoplasty was first described in 1976 to lengthen the palate to address wide clefts and foreshortened palates. This technique involves Z-plasty or transposition of soft palatal myomucosal flaps on 1 layer to recreate with transposition of mucosal flaps in a second layer to recreate the uvula. The myomucosal flap is raised on the nasal side on half of the palate, which is then transposed to a mucosal flap on the other side; the oral layer closure then uses an oral mucosal flap raised on the same side as the nasal myomucosal flap, which is then transposed to a myomucosal flap raised in the oral layer on the other side.[48] The Z-plasty technique allows for lengthening the palate (see Image. Furlow Palatoplasty).[49]

Straight-line mucoperiosteal flaps are elevated for the closure of the hard palate cleft, which can be combined with lateral relaxing incisions in the manner of von Langenbeck or with a V to Y pushback in the manner of Veau-Wardill-Killner to maximize palatal length and decrease tension.[50] With 45-degree limbs of the palatal Z-plasty limbs, a 25% overall lengthening of the palate is reportedly possible. Major critiques of this technique cite a potential for increased postoperative fistula rate, though this can be overcome with additional maneuver, eg, tendon transposition around the hook of the hamate.[51] This technique is also commonly employed in treating symptomatic submucus cleft palates.

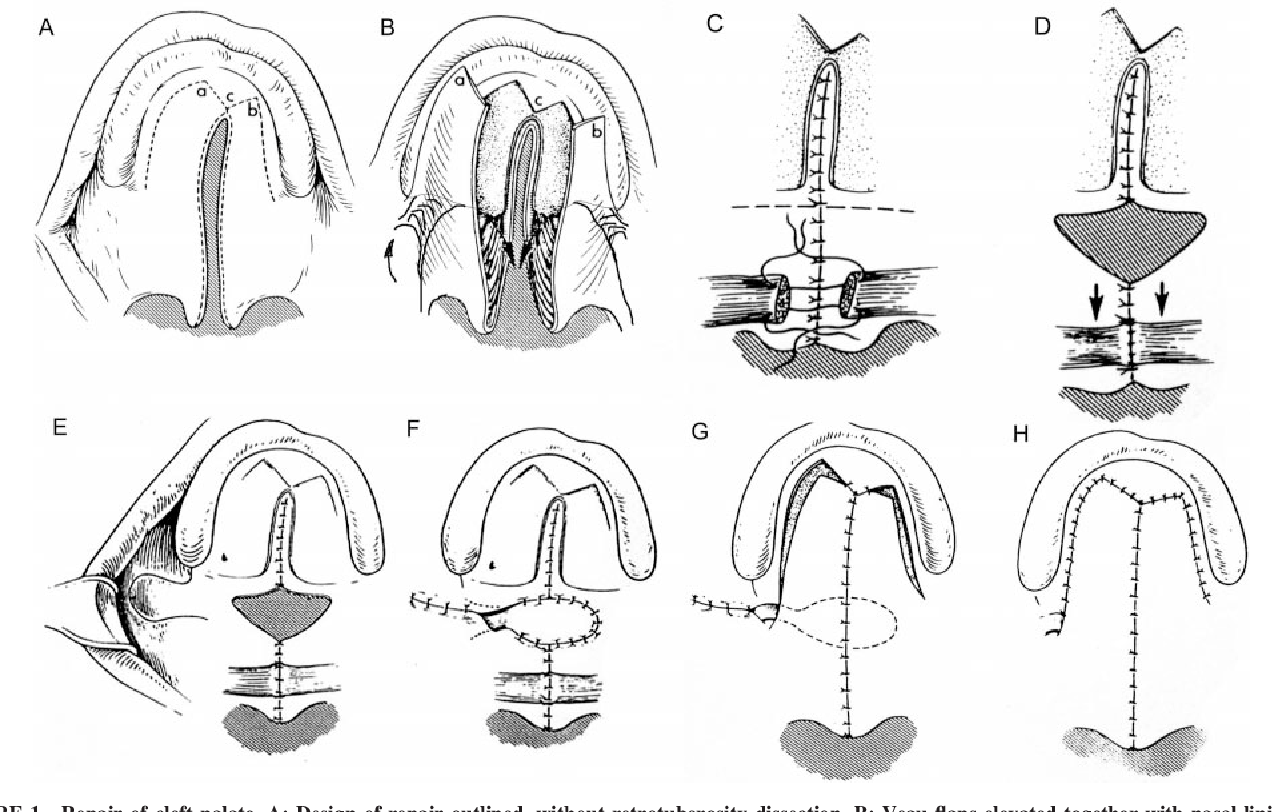

Buccal mucosal flaps

The use of concurrent buccal mucosal flaps, including facial artery musculomucosal flaps, more formal buccinator flaps, or buccal fat flaps, has been well-described in the revision setting when there has been a failure of prior repair and flap loss.[52] More recently, the use of such adjunctive flaps has been advocated in very wide clefts to reduce the tension on the palatal layer closure, to minimize dead space between the nasal and palatal layers, or as an additional source of mucosa and palatal length in extremely foreshortened palates (see Image. Buccal Mucosal Flap in Primary Palatoplasty).[53][54]

Bilateral Cleft Palate

By definition, a bilateral cleft palate involves the primary palate and can merge with the secondary palate in the form of a single cleft (see Image. Bilateral Cleft Palate). As a bilateral cleft means the prolabial segment is pedicled on the nasal septum and philtral portion of the lip, preservation of the blood supply to this segment is paramount when planning any surgery, as it is inherently tenuous.

Typically, the lip is repaired first, often according to the Manchester repair.[55] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Cleft Palate Repair," for more detailed information on surgical cleft palate repair.[56] This method allows alternate blood flow through the repaired lip segments rather than relying solely on the septal mucosal blood supply. Occasionally, the projection of the prolabial segment will be so profound that it precludes lip adhesion or other lip repair.[57] This is most common in children with bilateral cleft lip and palate that have gone unrepaired into early childhood (see Image. Severe Prolabial Segment Protrusion). If this is the case, a premaxillary setback should be performed and allowed to fully heal before addressing the clefts of the primary palate to avoid completely devascularizing the prolabial segment. Repair of the hard and soft palate may safely continue as per an algorithm for a unilateral cleft, with the repair of the alveolar clefts delayed.[58]

Primary palate and alveolar cleft repair practices and opinions differ among cleft centers. Some will opt to perform 1 side at a time, which theoretically may help contract the alveolar cleft on the other side but, most importantly, maximizes residual blood flow to the premaxillary segment.[59] The cleft can then be repaired with a gingivoperiosteoplasty (GPP) with or without bone grafting.[60]

Alveolar (Primary Palate) Cleft

If the cleft palate is isolated to the primary palate (alveolus and anterior to the incisive foramen), management options depend on the degree of clefting. If it is incomplete, and some bony continuity or soft-tissue continuity is present, then observation with possible bone grafting in the preteen years, with or without adjunct tissue-engineered materials, may be all that is necessary.[61]

If the alveolar cleft is a part of a complete cleft, which extends further into the secondary palate, then the management becomes more complicated. A narrow cleft can often be managed with a GPP at the same time as the formal palate repair, and this may avoid subsequent bone grafting by apposing the palatal shelves enough that bony continuity ensues.[62] Avoiding subsequent bone grafting may come at the expense of anterior palatal arch narrowing, though the data on this are widely variable.[51]

In patients where a GPP cannot be performed at the time of primary palatoplasty, then closure of the palate should proceed as per the cleft team's algorithm, with reassessment of the alveolar cleft annually at the interprofessional team meeting. When the child reaches school age, if the cleft is still symptomatic via nasal regurgitation or speech concerns, GPP should be entertained with or without bone grafting. If the fistula remains small and minimally symptomatic, then the GPP and bone grafting can be delayed until the preteen years, potentially minimizing the constrictive effects of GPP on midfacial growth but facilitating permanent dentition into the adult years.[63]

Differential Diagnosis

Cleft palate is often a straightforward diagnosis, though differentiation between incomplete cleft palate, bifid uvula, and submucous cleft palate is crucial. Identifying and excluding syndromes of which cleft palate can be a feature is also essential, including:

- CHARGE syndrome

- Stickler syndrome

- 22q11 deletion syndromes

- Pierre Robin sequence

- Various chromosomal deletions or duplications

Treatment Planning

Long-Term Cleft Care

The management of cleft palate ideally involves prenatal and postnatal treatment with an interprofessional team. The delineation of interventions and specialties involved varies according to each patient's condition and may be similar to the following timeline: [7]

- Antenatal period: Meet the team, cleft surgeon, genetic counseling

- Perinatal period: Genetic counseling, speech therapy counseling for feeding, lip taping or NAM, surgical assessment of degree of cleft and type

- Age 0 to 6 months: Hearing evaluation and possible ventilating tube placement, feeding and growth managed by speech therapy and pediatrician, cleft lip repair at 1 to 3 months with or without tip rhinoplasty depending on feeding status

- Age 9 to 12 months: Palate repair at 11 to 12 months, ventilating tube placement if needed and not already done, ongoing speech therapy for feeding

- Age 1 to 4 years: Close follow-up for language development, dental evaluation

- Age 4 to 6 years: Evaluation for palate revision/speech surgery, possible GPP or bone grafting of alveolar cleft, lip scar revision

- Age 6 to 12 years: Alveolar bone grafting, orthodontic intervention once mid-permanent dentition present, possible further lip scar revision or speech surgery if anatomy has changed

- Age 15 to 16 years: Consideration of primary rhinoplasty if midfacial growth on track, GPP, and bone grafting or another fistula repair if present, continuing orthodontics

- Age 18 to 21 years: Orthodontics and dental implantation, orthognathic surgery, orthodontics, genetic counseling for family planning [7]

Prognosis

The overall prognosis of a patient with cleft palate entirely depends upon the underlying medical condition. For patients with isolated CL/P, no difference in overall life expectancy or quality of life has been demonstrated when compared to age-matched controls once all repairs are complete. A significantly poorer age-matched quality of life in the childhood and teen years is noted; however, due to the required multiple surgical interventions.[64] In patients with underlying genetic syndromes, the prognosis and quality of life is guided almost entirely by global and systemic factors relating to the syndrome, with the cleft playing a relatively minor role in these metrics.[65]

Complications

The complications regarding cleft palate can be divided into those due to the cleft and those due to the repair.

Complications Due to an Unrepaired Cleft Palate

Complications due to a cleft palate are not really complications but rather sequelae. An unrepaired cleft palate adversely affects speech, swallowing, and psychosocial development. The dictum to repair each of these defects as soon as is safely possible underscores these concerns. While an unrepaired cleft lip is undoubtedly challenging for the family to manage, so long as adequate feeding and nutrition can be maintained, repair is delayed as long as possible while allowing for normal speech and feeding development.[66]

The optimal time for intervention of 11 to 12 months appears to the most effective for minimizing facial growth disturbances and long-term speech development issues. Likewise, the use of McGovern nipples on bottles, or breastfeeding, seeks to maximize feeding and nutrition, and the need for a nasogastric tube or other alternate alimentary feeding routes is uncommon in the absence of genetic syndromes.[67] The goal is to repair the palate and allow the child to become accustomed to using the repaired anatomy in the prelingual years. This approach maximizes speech, growth, nutritional, and development outcomes.

Complications Due to Palatoplasty

The major complications of palatoplasty are due to partial or complete failure of the repair, regardless of the technique employed. Palatoplasty can be complicated by wound dehiscence with or without fistula development. If a fistula develops, it can be small and clinically insignificant or large and clinically devastating.

Depending on the size and location of the postoperative fistula, revision surgery, obturator placement, or a combination may be required.[68] Orthodontic obturator placement can also serve as a stop-gap to facilitate normal speech development in young patients while awaiting a suitable time for a major revision palatoplasty. Persistent oronasal fistulae postoperatively pose the same spectrum of complications as an unrepaired cleft, including speech, swallowing, and nutritional problems.

Consultations

After neonatal delivery, CL/P management should involve an interprofessional healthcare team, including:

- Pediatrician/general practitioner

- Speech therapy (SLP)

- Medical genetics

- Otolaryngology

- Audiology

- Social work

- Orthodontics

- Dentistry

- Craniofacial surgery [10][31]

Deterrence and Patient Education

While some rare environmental factors are associated with cleft palate, the majority are spontaneous. A familial risk of approximately 2%, including spontaneous cases, of a parent with a cleft having a child with a cleft has been reported, even in the absence of a genetic syndrome.[69] Genetic counseling should therefore be offered to every family affected by CL/P, particularly for patients aging out of interprofessional teams that may be considering starting their own families. Genetic counseling is particularly significant in those patients and families with identified genetic syndromes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cleft palate, a congenital condition with lifelong implications, often requires an interprofessional approach for effective management, especially when linked with other syndromes. Beginning from infancy, this team typically includes primary care clinicians, speech-language pathologists, audiologists, genetic counselors, otolaryngologists, plastic surgeons, oral-maxillofacial surgeons, and social workers, and it may expand based on the specific needs of the patient and family. Throughout the timeline of care, this team works collaboratively to support the patient and family, providing seamless, patient-centered care that enhances outcomes and ensures safety.

Physicians and surgeons, including plastic and oral-maxillofacial specialists, lead in diagnosing and planning surgical interventions while coordinating ongoing treatment with the entire healthcare team. Advanced practitioners such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants complement this care by conducting assessments, managing follow-ups, and educating families on the recovery process and long-term care considerations. Nurses are central in delivering bedside care, monitoring recovery, and acting as a family's primary contact point, offering clinical guidance and emotional support. Pharmacists ensure safe medication management, advise on postsurgical pain relief and antibiotics, and educate families about medication adherence, which is critical for pediatric patients.

Speech therapists develop tailored plans to support postsurgical language development, while audiologists monitor and address the increased risk of hearing difficulties, ensuring that necessary interventions are smoothly integrated into the care plan. Nutritionists work closely with families to design feeding strategies that account for unique needs related to cleft palate, ensuring infants receive the nutrition they need despite feeding challenges.

Interprofessional communication among these professionals is essential for effective care coordination. The diverse insights and expertise shared within this collaborative approach allow for comprehensive care that supports the patient's holistic needs. By fostering a culture of shared responsibility, empathy, and open communication, the healthcare team not only improves outcomes and supports patient and family satisfaction but also upholds the highest standards of patient-centered care for individuals with cleft palate.