[1]

Corso A, Lazzarino M, Morra E, Merante S, Astori C, Bernasconi P, Boni M, Bernasconi C. Chronic myelogenous leukemia and exposure to ionizing radiation--a retrospective study of 443 patients. Annals of hematology. 1995 Feb:70(2):79-82

[PubMed PMID: 7880928]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[2]

Hoffmann VS, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Lindoerfer D, Burgstaller S, Sertic D, Costeas P, Mayer J, Indrak K, Everaus H, Koskenvesa P, Guilhot J, Schubert-Fritschle G, Castagnetti F, Di Raimondo F, Lejniece S, Griskevicius L, Thielen N, Sacha T, Hellmann A, Turkina AG, Zaritskey A, Bogdanovic A, Sninska Z, Zupan I, Steegmann JL, Simonsson B, Clark RE, Covelli A, Guidi G, Hehlmann R. The EUTOS population-based registry: incidence and clinical characteristics of 2904 CML patients in 20 European Countries. Leukemia. 2015 Jun:29(6):1336-43. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.73. Epub 2015 Mar 18

[PubMed PMID: 25783795]

[3]

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017 Jan:67(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. Epub 2017 Jan 5

[PubMed PMID: 28055103]

[4]

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018 Jan:68(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. Epub 2018 Jan 4

[PubMed PMID: 29313949]

[5]

Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, O'Brien S, Kurzrock R, Kantarjian HM. The biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Jul 15:341(3):164-72

[PubMed PMID: 10403855]

[6]

Jabbour E, Kantarjian H. Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2018 update on diagnosis, therapy and monitoring. American journal of hematology. 2018 Mar:93(3):442-459. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25011. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29411417]

[7]

Spiers AS, Bain BJ, Turner JE. The peripheral blood in chronic granulocytic leukaemia. Study of 50 untreated Philadelphia-positive cases. Scandinavian journal of haematology. 1977 Jan:18(1):25-38

[PubMed PMID: 265093]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

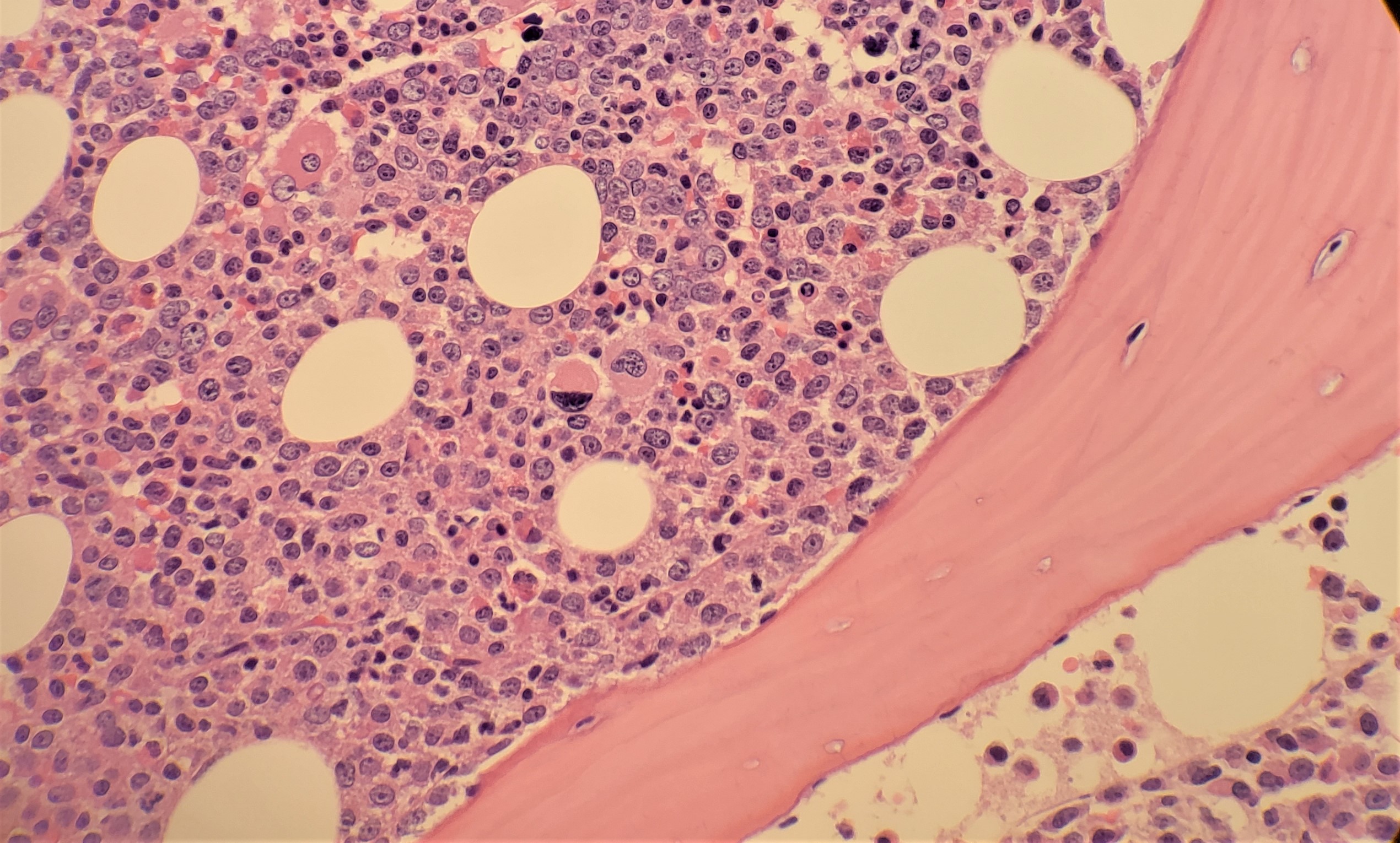

Thiele J, Kvasnicka HM, Fischer R. Bone marrow histopathology in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)--evaluation of distinctive features with clinical impact. Histology and histopathology. 1999 Oct:14(4):1241-56. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1241. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 10506940]

[9]

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, Bloomfield CD, Cazzola M, Vardiman JW. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016 May 19:127(20):2391-405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. Epub 2016 Apr 11

[PubMed PMID: 27069254]

[10]

Cortes JE, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Ferrajoli A, Verstovsek S, Rios MB, Shan J, Kantarjian HM. Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer. 2006 Mar 15:106(6):1306-15

[PubMed PMID: 16463391]

[11]

Sokal JE, Cox EB, Baccarani M, Tura S, Gomez GA, Robertson JE, Tso CY, Braun TJ, Clarkson BD, Cervantes F. Prognostic discrimination in "good-risk" chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1984 Apr:63(4):789-99

[PubMed PMID: 6584184]

[12]

Hasford J, Pfirrmann M, Hehlmann R, Allan NC, Baccarani M, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Alimena G, Steegmann JL, Ansari H. A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. Writing Committee for the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998 Jun 3:90(11):850-8

[PubMed PMID: 9625174]

[13]

Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saußele S, Pfirrmann M, Krause S, Kolb HJ, Neubauer A, Hossfeld DK, Nerl C, Gratwohl A, Baerlocher GM, Heim D, Brümmendorf TH, Fabarius A, Haferlach C, Schlegelberger B, Müller MC, Jeromin S, Proetel U, Kohlbrenner K, Voskanyan A, Rinaldetti S, Seifarth W, Spieß B, Balleisen L, Goebeler MC, Hänel M, Ho A, Dengler J, Falge C, Kanz L, Kremers S, Burchert A, Kneba M, Stegelmann F, Köhne CA, Lindemann HW, Waller CF, Pfreundschuh M, Spiekermann K, Berdel WE, Müller L, Edinger M, Mayer J, Beelen DW, Bentz M, Link H, Hertenstein B, Fuchs R, Wernli M, Schlegel F, Schlag R, de Wit M, Trümper L, Hebart H, Hahn M, Thomalla J, Scheid C, Schafhausen P, Verbeek W, Eckart MJ, Gassmann W, Pezzutto A, Schenk M, Brossart P, Geer T, Bildat S, Schäfer E, Hochhaus A, Hasford J. Assessment of imatinib as first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10-year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non-CML determinants. Leukemia. 2017 Nov:31(11):2398-2406. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.253. Epub 2017 Aug 14

[PubMed PMID: 28804124]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Baccarani M, Druker BJ, Branford S, Kim DW, Pane F, Mongay L, Mone M, Ortmann CE, Kantarjian HM, Radich JP, Hughes TP, Cortes JE, Guilhot F. Long-term response to imatinib is not affected by the initial dose in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: final update from the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Optimization and Selectivity (TOPS) study. International journal of hematology. 2014:99(5):616-24

[PubMed PMID: 24658916]

[15]

Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, de Souza CA, Guilhot F, Duvillié L, Pavlov D, Gogat K, Countouriotis AM, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Bosutinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia: results from the 24-month follow-up of the BELA trial. British journal of haematology. 2015 Jan:168(1):69-81. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13108. Epub 2014 Sep 8

[PubMed PMID: 25196702]

[16]

Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, Mayer J, Boqué C, Shah NP, Chuah C, Casanova L, Bradley-Garelik B, Manos G, Hochhaus A. Final 5-Year Study Results of DASISION: The Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Jul 10:34(20):2333-40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899. Epub 2016 May 23

[PubMed PMID: 27217448]

[17]

Nakamae H, Fukuda T, Nakaseko C, Kanda Y, Ohmine K, Ono T, Matsumura I, Matsuda A, Aoki M, Ito K, Shibayama H. Nilotinib vs. imatinib in Japanese patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: long-term follow-up of the Japanese subgroup of the randomized ENESTnd trial. International journal of hematology. 2018 Mar:107(3):327-336. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2353-7. Epub 2017 Oct 26

[PubMed PMID: 29076005]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[18]

Müller MC, Cervantes F, Hjorth-Hansen H, Janssen JJWM, Milojkovic D, Rea D, Rosti G. Ponatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): Consensus on patient treatment and management from a European expert panel. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2017 Dec:120():52-59. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.10.002. Epub 2017 Oct 8

[PubMed PMID: 29198338]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[19]

Khoury HJ, Cortes J, Baccarani M, Wetzler M, Masszi T, Digumarti R, Craig A, Benichou AC, Akard L. Omacetaxine mepesuccinate in patients with advanced chronic myeloid leukemia with resistance or intolerance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2015 Jan:56(1):120-7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.889826. Epub 2014 Apr 28

[PubMed PMID: 24650054]

[20]

Nair AP, Barnett MJ, Broady RC, Hogge DE, Song KW, Toze CL, Nantel SH, Power MM, Sutherland HJ, Nevill TJ, Abou Mourad Y, Narayanan S, Gerrie AS, Forrest DL. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Is an Effective Salvage Therapy for Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Presenting with Advanced Disease or Failing Treatment with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015 Aug:21(8):1437-44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.005. Epub 2015 Apr 10

[PubMed PMID: 25865648]

[21]

Kwak JY, Kim SH, Oh SJ, Zang DY, Kim H, Kim JA, Do YR, Kim HJ, Park JS, Choi CW, Lee WS, Mun YC, Kong JH, Chung JS, Shin HJ, Kim DY, Park J, Jung CW, Bunworasate U, Comia NS, Jootar S, Reksodiputro AH, Caguioa PB, Lee SE, Kim DW. Phase III Clinical Trial (RERISE study) Results of Efficacy and Safety of Radotinib Compared with Imatinib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2017 Dec 1:23(23):7180-7188. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0957. Epub 2017 Sep 22

[PubMed PMID: 28939746]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[22]

Guilhot F, Druker B, Larson RA, Gathmann I, So C, Waltzman R, O'Brien SG. High rates of durable response are achieved with imatinib after treatment with interferon alpha plus cytarabine: results from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS) trial. Haematologica. 2009 Dec:94(12):1669-75. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.010629. Epub 2009 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 19648168]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[23]

Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, Mauro MJ, Chuah C, Kim DW, Dyagil I, Glushko N, Milojkovic D, le Coutre P, Garcia-Gutierrez V, Reilly L, Jeynes-Ellis A, Leip E, Bardy-Bouxin N, Hochhaus A, Brümmendorf TH. Bosutinib Versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Results From the Randomized BFORE Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Jan 20:36(3):231-237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.7162. Epub 2017 Nov 1

[PubMed PMID: 29091516]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[24]

Etienne G, Guilhot J, Rea D, Rigal-Huguet F, Nicolini F, Charbonnier A, Guerci-Bresler A, Legros L, Varet B, Gardembas M, Dubruille V, Tulliez M, Noel MP, Ianotto JC, Villemagne B, Carré M, Guilhot F, Rousselot P, Mahon FX. Long-Term Follow-Up of the French Stop Imatinib (STIM1) Study in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Jan 20:35(3):298-305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2914. Epub 2016 Oct 31

[PubMed PMID: 28095277]

[25]

Ross DM, Masszi T, Gómez Casares MT, Hellmann A, Stentoft J, Conneally E, Garcia-Gutierrez V, Gattermann N, le Coutre PD, Martino B, Saussele S, Giles FJ, Radich JP, Saglio G, Deng W, Krunic N, Bédoucha V, Gopalakrishna P, Hochhaus A. Durable treatment-free remission in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase following frontline nilotinib: 96-week update of the ENESTfreedom study. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2018 May:144(5):945-954. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2604-x. Epub 2018 Feb 22

[PubMed PMID: 29468438]

[26]

Mori S, Vagge E, le Coutre P, Abruzzese E, Martino B, Pungolino E, Elena C, Pierri I, Assouline S, D'Emilio A, Gozzini A, Giraldo P, Stagno F, Iurlo A, Luciani M, De Riso G, Redaelli S, Kim DW, Pirola A, Mezzatesta C, Petroccione A, Lodolo D'Oria A, Crivori P, Piazza R, Gambacorti-Passerini C. Age and dPCR can predict relapse in CML patients who discontinued imatinib: the ISAV study. American journal of hematology. 2015 Oct:90(10):910-4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24120. Epub 2015 Sep 10

[PubMed PMID: 26178642]

[27]

Saussele S, Richter J, Guilhot J, Gruber FX, Hjorth-Hansen H, Almeida A, Janssen JJWM, Mayer J, Koskenvesa P, Panayiotidis P, Olsson-Strömberg U, Martinez-Lopez J, Rousselot P, Vestergaard H, Ehrencrona H, Kairisto V, Machová Poláková K, Müller MC, Mustjoki S, Berger MG, Fabarius A, Hofmann WK, Hochhaus A, Pfirrmann M, Mahon FX, EURO-SKI investigators. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): a prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2018 Jun:19(6):747-757. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30192-X. Epub 2018 May 4

[PubMed PMID: 29735299]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[28]

Hehlmann R. CML--Where do we stand in 2015? Annals of hematology. 2015 Apr:94 Suppl 2():S103-5. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2331-1. Epub 2015 Mar 27

[PubMed PMID: 25814076]

[29]

Lima L, Bernal-Mizrachi L, Saxe D, Mann KP, Tighiouart M, Arellano M, Heffner L, McLemore M, Langston A, Winton E, Khoury HJ. Peripheral blood monitoring of chronic myeloid leukemia during treatment with imatinib, second-line agents, and beyond. Cancer. 2011 Mar 15:117(6):1245-52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25678. Epub 2010 Nov 2

[PubMed PMID: 21381013]

[30]

Faderl S, Talpaz M, Estrov Z, Kantarjian HM. Chronic myelogenous leukemia: biology and therapy. Annals of internal medicine. 1999 Aug 3:131(3):207-19

[PubMed PMID: 10428738]

[31]

Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, Branford S, Radich J, Kaeda J, Baccarani M, Cortes J, Cross NC, Druker BJ, Gabert J, Grimwade D, Hehlmann R, Kamel-Reid S, Lipton JH, Longtine J, Martinelli G, Saglio G, Soverini S, Stock W, Goldman JM. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR-ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood. 2006 Jul 1:108(1):28-37

[PubMed PMID: 16522812]

[32]

Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF, Cervantes F, Clark RE, Cortes JE, Guilhot F, Hjorth-Hansen H, Hughes TP, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, Larson RA, Lipton JH, Mahon FX, Martinelli G, Mayer J, Müller MC, Niederwieser D, Pane F, Radich JP, Rousselot P, Saglio G, Saußele S, Schiffer C, Silver R, Simonsson B, Steegmann JL, Goldman JM, Hehlmann R. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013 Aug 8:122(6):872-84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569. Epub 2013 Jun 26

[PubMed PMID: 23803709]

[33]

Nazha A, Kantarjian H, Jain P, Romo C, Jabbour E, Quintas-Cardama A, Luthra R, Abruzzo L, Borthakur G, Ravandi F, Pierce S, O'Brien S, Cortes J. Assessment at 6 months may be warranted for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with no major cytogenetic response at 3 months. Haematologica. 2013 Nov:98(11):1686-8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.090282. Epub 2013 Jun 28

[PubMed PMID: 23812943]

[34]

Ibrahim AR, Eliasson L, Apperley JF, Milojkovic D, Bua M, Szydlo R, Mahon FX, Kozlowski K, Paliompeis C, Foroni L, Khorashad JS, Bazeos A, Molimard M, Reid A, Rezvani K, Gerrard G, Goldman J, Marin D. Poor adherence is the main reason for loss of CCyR and imatinib failure for chronic myeloid leukemia patients on long-term therapy. Blood. 2011 Apr 7:117(14):3733-6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-309807. Epub 2011 Feb 23

[PubMed PMID: 21346253]

[35]

Caldemeyer L, Akard LP. Rationale and motivating factors for treatment-free remission in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2016 Dec:57(12):2739-2751

[PubMed PMID: 27562641]

[36]

Steegmann JL, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Casado LF, García-Gutiérrez V, Hochhaus A, Kim DW, Kim TD, Khoury HJ, Le Coutre P, Mayer J, Milojkovic D, Porkka K, Rea D, Rosti G, Saussele S, Hehlmann R, Clark RE. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management and avoidance of adverse events of treatment in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2016 Aug:30(8):1648-71. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.104. Epub 2016 Apr 28

[PubMed PMID: 27121688]

[37]

Wang W, Cortes JE, Tang G, Khoury JD, Wang S, Bueso-Ramos CE, DiGiuseppe JA, Chen Z, Kantarjian HM, Medeiros LJ, Hu S. Risk stratification of chromosomal abnormalities in chronic myelogenous leukemia in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Blood. 2016 Jun 2:127(22):2742-50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-690230. Epub 2016 Mar 22

[PubMed PMID: 27006386]

[38]

Ernst T, La Rosée P, Müller MC, Hochhaus A. BCR-ABL mutations in chronic myeloid leukemia. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2011 Oct:25(5):997-1008, v-vi. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2011.09.005. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22054731]

[39]

Branford S, Wang P, Yeung DT, Thomson D, Purins A, Wadham C, Shahrin NH, Marum JE, Nataren N, Parker WT, Geoghegan J, Feng J, Shanmuganathan N, Mueller MC, Dietz C, Stangl D, Donaldson Z, Altamura H, Georgievski J, Braley J, Brown A, Hahn C, Walker I, Kim SH, Choi SY, Park SH, Kim DW, White DL, Yong ASM, Ross DM, Scott HS, Schreiber AW, Hughes TP. Integrative genomic analysis reveals cancer-associated mutations at diagnosis of CML in patients with high-risk disease. Blood. 2018 Aug 30:132(9):948-961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-02-832253. Epub 2018 Jul 2

[PubMed PMID: 29967129]