Continuing Education Activity

A chest tube, or a thoracostomy tube, is a flexible tube that can be inserted through the chest wall and into the pleural space. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications, and technique involved in placing a chest tube and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients undergoing this procedure.

Objectives:

Assess the anatomy of the chest cavity relevant to chest tube placement.

Identify the equipment needed for the insertion of a chest tube.

D1 the indications for a chest tube.

1Explain a structured interprofessional team approach to provide effective care to and appropriate surveillance of patients undergoing chest tube placement.

Introduction

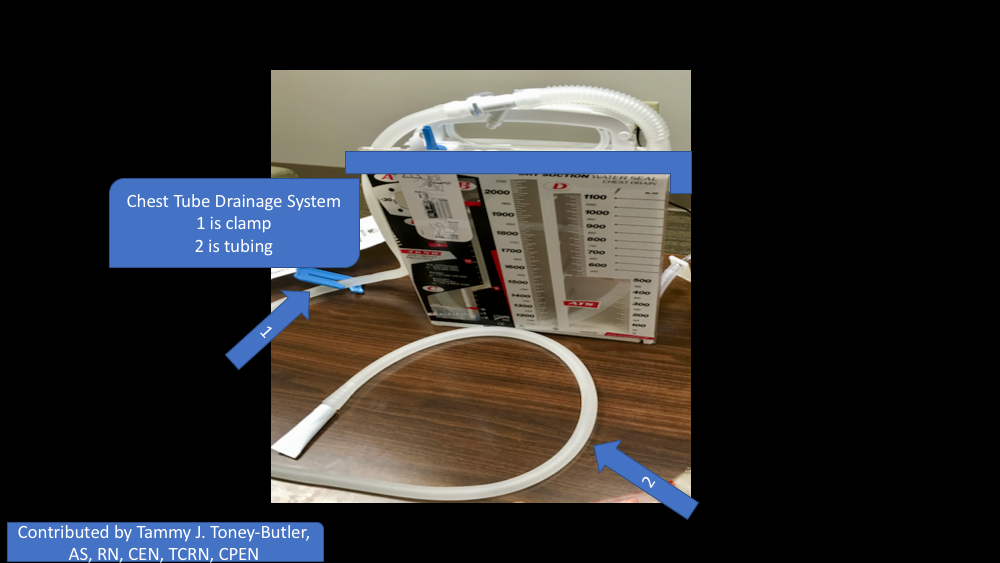

A chest tube, or a thoracostomy tube, is a flexible tube that can be inserted through the chest wall between the ribs into the pleural space. Thoracostomy tubes are commonly made from PVC or silicone. They range from 6 French to 40 French. Most are fenestrated along the sides of the insertion end, and the tubes have a radiopaque stripe. After placement, the distal end of the tube is connected to a pleura-evac system. There are 3 chambers of a pleura-evac: the suction chamber, the water seal chamber, and the collection chamber. The water seal chamber acts as a one-way valve, allowing air to escape from gravity but not to re-enter the thoracic cavity.[1][2][3] See Image. Chest Tube Example.

Indications

Physicians use a chest tube to create negative pressure in the chest cavity and allow lung re-expansion. It helps remove air (pneumothorax), blood (hemothorax), fluid (pleural effusion or hydrothorax), chyle (chylothorax), or purulence (empyema) from the intrathoracic space. There are other uses for a thoracostomy tube that are not as common and rarely indicated. Typical for a tension pneumothorax needle, decompression occurs first, and chest tube placement quickly follows after the patient stabilizes from decompression.

Contraindications

Relative contraindications to chest tube placement include pulmonary adhesions from previous surgery, pulmonary disease, and/or trauma. Coagulopathy and diaphragmatic hernias can be contraindications as well.

Technique or Treatment

Placement: A thoracostomy tube is usually placed between the mid to anterior axillary line in the fourth or fifth intercostal space, tracking above the rib so as not to injure the intercostal bundle (artery, vein, nerve). The fourth intercostal space is normally at nipple level on males or inframammary fold on females. Tracking up and over 1 rib space is preferred, so a soft tissue "flap" is present upon removal of the thoracostomy tube to prevent outside air from tracking back into the thoracic cavity after removal, causing a persistent or recurrent pneumothorax. Ultrasound or computed tomography can guide the placement of a chest tube. These imaging methods are more useful in more complicated patients with a history of infection or surgery. This puts them at a higher risk for scarring. Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered before placement in the elective operative or trauma setting. Follow-up imaging (chest radiography) is customary after placement to confirm the correct positioning of the thoracostomy tube. Usually, for pneumothorax, a straight tube is placed toward the apex. For hemothorax or pleural effusion, a straight tube is typically placed posterior and toward the apex, and/or a right-angled tube can be placed at the base of the lung and diaphragm.

Discontinuation: Upon removal, try to avoid discontinuing the tube upon inspiration because this develops a pressure gradient inside the chest that can have air track intrathoracic and cause a persistent/recurrent pneumothorax after discontinuation. There are several tricks to prevent this from occurring. One is to time the discontinuation and synchronize with the patient's breathing. Another trick is to have the patient hold their breath or make a seal and blow on their thumb like blowing up a balloon. An occlusive dressing with Vaseline or Xeroform gauze is preferred, or placing a U-stitch around the incision site and tightening when the tube is discontinued is another option.[4][5]

Complications

The complications that can manifest with chest tubes are as follows:

- Bleeding

- Superficial site infection

- Deep organ space infection (empyema)

- Dislodgement of the tube

- Clogging of the tube

- Re-expansion pulmonary edema

- Injury to intraabdominal organs such as the spleen or liver

- Injury to the diaphragm

- Injury to intrathoracic organs, such as the heart or thoracic aorta

Clinical Significance

A chest tube provides life-saving removal of air, blood, and infectious fluids.

Management of Chest Tube

The standard management of chest tubes has yet to be scientifically determined or agreed upon by experts. It is often physician-specific based on their training and anecdotal experience; it is not an exact science. Depending on the indication for the thoracostomy tube placement, the overall concept of managing 1 is based on the favorable opposition of the visceral and parietal pleura. The 3 options for managing a chest tube are suction, water seal, and clamping.

When a new air leak is noted, the chest tube, connecting tubing, pleura-evac, and a patient's wound should be examined for any loose connections or dislodgement of the tube. The fenestrated holes should not be outside of the body. Factors that put a patient at high risk for persistent air leaks include steroid use, emphysematous lungs, re-operation with extensive scar tissue, or significant trauma to the lungs.

Suction is usually the initial chest tube management for most indications, not including specialized thoracic surgeries. The tube can then be placed on a water seal if there is no air leak or pneumothorax on a chest X-ray (see Image. Chest Tube, X-ray). Chest tubes placed for pleurodesis and decortication usually need to be on suction longer to aid in opposition of the pleura before discontinuing the tube. The chest tube can be discontinued once no air leak is visualized, output is serosanguinous with no signs of bleeding, output is less than 150 cc to 400 cc over 24 hours (this range is wide because it is debatable among researchers), nonexistent or stable mild pneumothorax on chest x-ray. The patient is minimized on positive pressure from the ventilator. A thoracic surgical specialist must be consulted if a patient has a persistent leak after the previous management mentioned above. Suppose the thoracostomy tube is placed for traumatic hemothorax. In that case, the indications for a thoracotomy include an initial sanguineous output of 1500 cc or an average of 200 cc/hr over 4 hours consecutive hours.

For post-traumatic retained hemothorax, the literature is shifting toward early video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) if thoracostomy tube management fails. Some of the options for management included placement of a second chest tube versus tPA administration through the tube if you think the hemothorax has turned into a clot. Some trauma or CT surgeons are now taking patients straight to VATS if there is a retained hemothorax after the first thoracostomy tube.[6]

Considerations

Small thoracostomy tubes (such as Wayne catheters) are meant to treat pneumothorax over hemothorax or effusion secondary to the risk of clogging. Larger chest tubes, usually 28 French or larger, are needed for drainage of blood or pus in adults.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chest tubes are now routinely used in most hospitals. Patients may have a chest tube inserted for various reasons, and the management requires a team approach. Besides physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists must be familiar with chest tubes and drainage kits. Not only do chest tubes require regular dressing changes, but 1 must also ensure that the connections are secure and the drainage kit is functioning. See Image. Chest Tube Drainage System. Listening to the patient's chest and regular chest X-rays are the norm. Nurses need to know how to manage dislodgement or disconnections of chest tubes and how to assess the patient. Finally, the surgeon should be consulted if a clinician doubts the chest tube.[7][8] Interprofessional teamwork ensures the best outcomes with chest tubes.

Outcomes

Most people who require a chest tube for a pneumothorax, empyema, or pleural effusion have a good outcome if the condition is benign. However, chest tubes do have complications that include bleeding, injury to the internal organs, and dislodgement. The rates of these complications vary from 1 to 10%, depending on the institution. Over the past 2 decades, smaller chest tubes have become available, are easier to insert, and are associated with significantly less pain than older chest tubes.[7][9]