Introduction

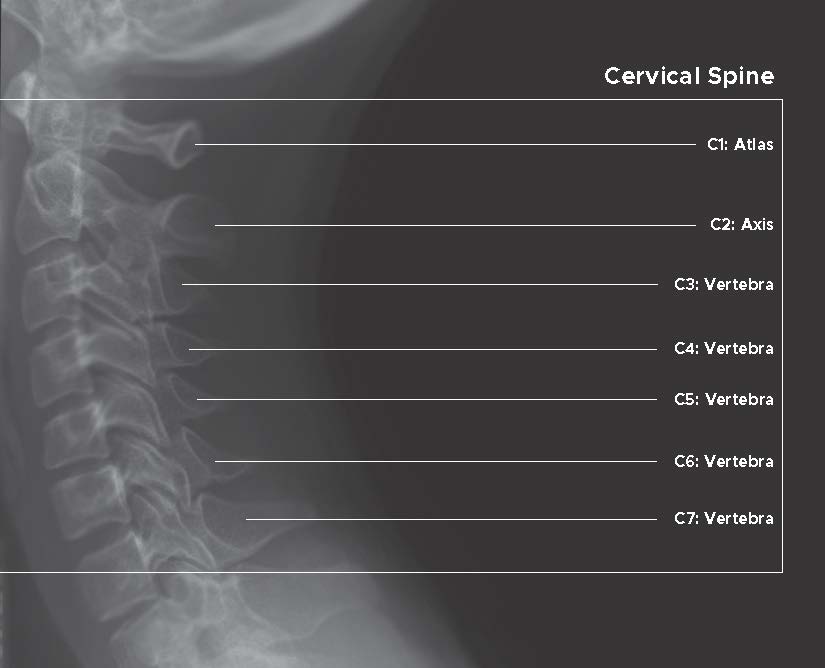

The human vertebral column or spine has five distinct anatomical regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. However, the cervical spine is a potential area of importance due to its proximity to the head, containment of the upper spinal cord, and vertebral arteries that contribute to the posterior circulation of the brain. Seven cervical vertebrae, combined with cartilages, various ligaments, and muscles, make a sophisticated and flexible structure that allows a variety of head/neck movements. Similar to other areas of the spine, cervical vertebrae also have intervening intervertebral disks for shock absorption and flexibility. Additionally, it contains a much wider spinal canal to accommodate the spinal cord, blood vessels, meninges, and nerve roots.[1]

Structure and Function

Each vertebra of the spinal column is usually made up of a body, spinous process, vertebral foramen, bilateral transverse processes, and pairs of superior and inferior articular facets. Cervical vertebrae have unique anatomical features that distinguish them well from other spine areas. Their bifid spinous processes provide a space for nuchal ligamental attachment, and triangular vertebral foramina accommodate the thicker cervical spinal cord. The third unique characteristic is the presence of transverse foramina, which transmits vertebral arteries on either side of the cervical spine. Besides this, anatomical and functional similarity provides an opportunity to describe the cervical vertebrae into the upper and lower cervical spine.

Upper Cervical Spine (C1-C2)

Atlas (C1) and axis (C2) are the first two cervical vertebrae and are named separately due to their distinctive anatomical features. They reside in the spine's craniovertebral junction, where the base of the skull meets the spinal column. The ring-shaped atlas lacks a body and spinous process, potentially responsible for supporting the head. While working together, the atlas and axis primarily allow spinal rotation, flexion, and extension; and are thus considered the most flexible segment of the entire spine.

Atlas is a unique ring-shaped vertebra lacking a vertebral body that articulates with the occiput above and axis below by corresponding condyles on its lateral masses. While in the medial aspect, the odontoid process of axis or dens articulates with an anterior arch of the axis as the median atlantoaxial joint. The odontoid process of axis or dens is the remnant of the C1 body that fused with the body of the axis and became a unique identity for C2. This median atlantoaxial joint allows free rotation of the head without involving the trunk. A transverse ligament runs posterior to the dens and attaches with either lateral mass of the atlas, preventing anterior subluxation of the atlas on the axis.[2][3][4][5]

Lower Cervical Spine (C3-C7)

In contrast with the upper cervical vertebrae, all five vertebrae in the lower cervical spine possess a vertebral body with superior concave and inferior convex surfaces. The uncinate process is a characteristic feature of lower cervical vertebrae that articulates with a depressed area of the adjacent upper vertebral body. This articulation provides additional stability and prevents cervical vertebral listhesis (spondylolisthesis). Additionally, C7 has a slightly larger vertebral body and smaller vertebral foramen than other cervical vertebrae and does not contain the vertebral artery. Having inferior facets and spinous processes, it resembles thoracic vertebrae hence called transitional vertebrae.[3][6]

Vertebral articulations in the spinal column integrate vertebral foramina into a continuous canal named the spinal canal, whereas intervertebral foramina form on either side of each pair of vertebrae. The Intervertebral foramen or neuroforamen is bounded by the superior notch and inferior notch of the corresponding vertebrae and acts as an exit path for spinal nerve rootlets. Among the eight pairs of cervical spinal nerves, C1-C7 rootlets exit the spinal canal through the superior notch of corresponding cervical vertebrae and C8 through the inferior notch of the C7 vertebra.

Ligaments

The vertebral column has some ligaments which are present throughout the spine. But there are a few ligaments that are unique and present in the cervical spine only. Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligament (covering the vertebral body ), ligamentum flavum (connects the laminae), and interspinous ligament (connects the spinous process) are present at every vertebral level, whereas the nuchal ligament (connects the tip of the spinous process and provides attachment for muscles) and transverse ligament of the atlas are present in the cervical spine only. Ligaments of the cervical spine can further group as external and internal ligaments. Examples of the outer ligaments are atlanto-occipital, anterior atlantooccipital, and anterior longitudinal ligaments. Examples of internal ligaments are the transverse ligaments, the accessory ligaments, the alar ligaments, the accessory atlantoaxial ligament, and the tectorial membrane.[7]

Intervertebral Discs

Cervical intervertebral discs facilitate motion, transmit weight, and provide stability to the spine. Each disc has four parts, the central nucleus pulposus, which is surrounded by annulus fibrosus, and two end plates, which are attached to the body of the vertebrae. Intervertebral discs are thicker anteriorly, and for this thickening, they are responsible for physiological lordosis of the neck.[8]

Movements of the Cervical Spine

The cervical spine's flexibility provides a wide range of motion, including flexion, extension, rotation, and lateral flexion. The atlantoaxial joint offers 50% of all cervical rotation. Besides, the atlantooccipital joint contributes 50% of flexion and extension of the neck.

- Flexion: Forward bending of the cervical spine. It occurs while looking downwards.

- Extension: Bending backward or straightening of the cervical spine. Example: performing overhead work.

- Rotation: Turning the head, along with the cervical spine, to one side. Example: Looking at the shoulder.

- Lateral flexion: Bending of cervical spine laterally to the right or left side.[9]

Functions of Cervical Spine

The cervical spine plays many roles in the head-neck area, including:

- Protection of the spinal cord: It is a bundle of nerve fiber that is a continuation of the brain stem. The spinal cord traverse through a canal in the vertebral column called the spinal canal. The cervical spine protects it from external compression.

- Provide support to the head: The cervical spine holds the head in position and bears its weight.

- Supports blood supply to the brain: The cervical spine carries a vertebral artery in its transverse foramen and helps them to send blood to the brain.

- Supports Head-Neck movements: Cervical spine and neck muscle provide a wide range of motion in this region.[10]

Embryology

Vertebrae begin their development at approximately eight weeks of gestation from somites, which are a part of the paraxial mesoderm. Under the influence of the notochord, somites convert into sclerotome, dermatome, and myotome. Sclerotome gives rise to vertebrae, while muscles derived from myotome and overlying dermis from dermatome. All of these developmental events proceed in craniocaudal directions.[11][12]

The cervical spine arises from three different primary ossification sites: the anterior arch and the two neural arches. The anterior arch and neural arches convert into the vertebral body and pedicles, respectively. The neural arches fuse by 2 to 3 years of life, which later unite the body between 3 and 6 years of age. During the developmental period, this "non-fusion" may be misinterpreted as a fracture. Fortunately, the sclerotic margin helps differentiate it from fracture. The axis (C2) has four ossification centers: one for the vertebral body, two for the neural arch, and one for the odontoid process. The body and the odontoid process fuse by 4 to 6 years of age.[5]

Five distinct secondary ossification centers of the cervical spine arise during puberty. They are distributed in the spinous process, in both transverse processes and surfaces. The vertebral body grows in the superior-inferior direction by the contribution of this ossification center. By the age of 25, this developmental process becomes complete.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Vertebral and carotid arteries traverse through the cervical region on each side. But only the vertebral arteries supply the spines through the cervical radicular arteries. The vertebral artery is a branch of the subclavian artery that enters the cervical region through the foramen in the transverse process of C6 and then travels through the cervical spine to course into the base of the skull. Vertebral arteries from each side join together and form the basilar artery that supplies the brainstem. The brachiocephalic artery gives rise to the right common carotid artery, and the arch of the aorta gives rise to the left common carotid artery. Then they bifurcate into the external and internal carotid artery at the level of the C3 vertebrae.[13]

Nerves

The cervical spine accommodates the spinal cord as it exits the skull. Each cervical spine has two nerve roots on each side, which arise from the spinal cord in the vertebral foramen. They are the ventral root (located posteriorly) and the dorsal root (located anteriorly). The ventral root carries motor signals and supplies them to muscles. The dorsal root sends sensory signals to the brain from dermatomal distribution. Both roots merge in the spinal foramen and become spinal nerves. There are eight cervical spinal nerves, despite only seven cervical vertebrae. Each nerve exits cranially to its corresponding vertebrae except C8, which exits caudally to the C7 vertebrae.[14]

Muscles

The cervical vertebrae serve as the origin and insertion points for muscles that support and facilitate head and neck movements. Posteriorly, the erector spine muscles of the deep back traverse the entire length of the spine and insert onto the spinous and transverse processes of the upper thoracic and cervical vertebrae. These muscles provide postural support and assist in flexion and extension of the vertebral column. The muscles of the posterior neck and suboccipital triangle are associated with the cervical vertebrae and enable the extension, rotation, and lateral bending of the neck. These include:

- Suboccipital muscles:

- Rectus capitis posterior major

- Rectus capitis posterior minor

- Oblique capitus supoerior

- Oblique capitis inferior

- Longissimus capitis

- Semispinalis capitis

- Semispinalis cervicus

- Splenius capitis

- Splenius cervicus

The anterior neck muscles also originate at various landmarks of cervical vertebrae before attaching to the skull or first or second ribs. These muscles are responsible for neck flexion, rotation, lateral bending, and stabilization of the skull. These include:

- Sternocleidomastoid (SCM)

- Scalenes

- Platysma

Note: the above does not include the deep muscles of the anterior neck in the submental, submandibular, and carotid triangles, whose primary functions are not related to gross cervical motion but do participate in neck movement to a lesser degree.

Several other muscles with cervical spinal attachments that participate significantly in neck movement include the trapezius, interspinales, levator scapulae, semispinalis, and rhomboid minor.[15][4]

Physiologic Variants

Cervical vertebrae are unique from other vertebrae in many ways. The bifid spinous process is one of Them. But not all cervical vertebrae of all individual has a bifid spinous process. Many studies show that only C2-C4 possess bifid spinous processes consistently. The prevalence is lowest for the C7 spine (0.3% of the population.) Therefore, using this parameter to identify cervical vertebrae is not always reliable.[16][17] The vertebra is separated by an intervertebral disc, which is absent between C1-C2.

Secondary ossification centers in the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body contribute to the development of the growth plate. Any interruption in this process can result in a significant congenital abnormality in cervical vertebrae.[11]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical consideration is an option for many pathologies in the cervical spine. Many vital structures surround the cervical spine, for example, the trachea, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, vertebral arteries, carotid arteries, thyroid gland, and parathyroid glands. So, any surgical intervention should be performed cautiously with proper hemostasis and proper use of a retractor to prevent or minimize injury to these structures. The cervical spine can be accessed anteriorly or posteriorly. The mode of pathology and the surgeon's preference determines the side (right or left). Each approach has its complications. The anterior approach is better if access to the vertebral body is necessary. It is appropriate for addressing fractures, infections, disc replacement, tumor resection, corpectomy, and fusion. To reach the cervical spine, skin and platysma muscle are first dissected, then sternocleidomastoid muscle, carotid sheath, and its content and other vital structures are identified and protected first. Infection, abscess, and hematoma formation are common complications.[18][19][20]

Neurovascular injury or adjacent organ injuries are severe complications. Dysphagia due to damage to the vagus nerve or pharynx, dysphonia due to injury to the laryngeal nerve or larynx, and difficulty swallowing due to injury to the pharynx may occur.[21][22] Injury to the stellate ganglion (located at the C6 level) can cause Horner syndrome. This syndrome presents with ptosis, anhydrosis, and miosis. Therefore, evaluation of the postoperative complication is necessary. A lateral X-ray of the spine is usually done after the operative procedure to see if any soft tissue swelling is present or not. If any swelling is present, the determination of its size is essential. The swelling should not exceed 10 mm at C1, 5 mm at C3, and 15 to 20 mm at C6 spinal level in a healthy inflammatory response.[2]

A posterior approach is useful to access elements of the cervical spine that locates posteriorly. Standard procedures are posterior cervical spine instrumentation, removal of laminae, repair of laminae, C3 to C6 spine has small pedicles, so pedicle screw fixation is difficult through a posterior approach. Instead, a lateral approach is a proper method. Due to the close relation of the vertebral artery, during the lateral procedure, it may suffer injury—the vertebral artery courses laterally from the C1 spine. When placing a screw at the C1 spine, it should be angled medially 10 to 15 degrees to prevent vertebral artery injury. Any operative procedure that may involve or cause fusion of C1 and C2 can be complicated by restriction of movement of the atlantoaxial joint. The patient should receive counsel regarding this risk.[2]

Clinical Significance

Neck pain is a common disability, particularly in older people. The annual prevalence rate of neck pain is more than 30%. It can be classified according to etiology (mechanical, neuropathic, or referred) or duration (acute, subacute, or chronic.). Many rheumatologic conditions are also associated with neck pain, such as chronic rheumatoid arthritis.[3][23] Any cause of neck pain should be evaluated and treated promptly. Otherwise, it may be followed by long-term disabilities. Proper history, examination, and investigations can differentiate neuropathic pain from mechanical neck pain. Initially, an X-ray may be used to visualize any dislocation or fractures. Computed tomography (CT) has superiority over X-ray. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to better view any soft tissue (spinal cord or ligament) injury.[23][24]

Acute neck pain is the most common presentation in traumatic or sports injuries. Immediate stabilization is necessary to prevent long-term complications. Fracture or dislocation is prevalent in the upper cervical spine. Approximately 2% of all vertebral fracture is composed of atlas fracture. The anterior and posterior arches are the weakest points in the atlas. This fracture is called a Jefferson fracture. It is managed by cranial traction and immobilization. The transverse ligament may be injured in Jefferson fracture, which may be followed by spinal cord injury. So, urgent treatment by occipital-cervical arthrodesis is necessary.[25]

Hyperflexion or extension may cause a fracture in the odontoid process. Displacement of one vertebra over another may also happen. This is termed spondylolisthesis. It is followed by acute pain and neurological features. Hanging or high-intensity collision injury can cause bilateral spondylolisthesis of C2. Here the pedicles of the C2 vertebrae break symmetrically, and the body of C2 becomes displaced. This fracture is known as a hangman's fracture. This is a severe injury and can be followed by death or full-body paralysis.

Chronic rheumatologic or degenerative diseases are associated with Subacute or chronic neck pain. Degeneration is usually seen in older adults above 40 years of age. It may cause compression of nerve roots and may cause cervical radiculopathy. Disc herniation and stenosis are other reasons for neuropathic pain. Chronic rheumatoid arthritis causes atlantoaxial joint instability. Hyperextension in the intubation process can cause atlantoaxial subluxation, which may be followed by spinal shock.[26]