Continuing Education Activity

Cerebral aneurysms are defined as dilations that occur at weak points along the arterial circulation within the brain. The majority of cerebral aneurysms are silent and may be found incidentally on neuroimaging or upon autopsy. Approximately 85% of aneurysms are located in the anterior circulation, predominately at junctions or bifurcations along the circle of Willis. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) usually occurs with rupture and is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with a cerebral aneurysm.

Objectives:

Review the cause of cerebral aneurysms.

Describe the presentation of a cerebral aneurysm.

Summarize the treatment of cerebral aneurysms.

Explain the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with a cerebral aneurysm.

Introduction

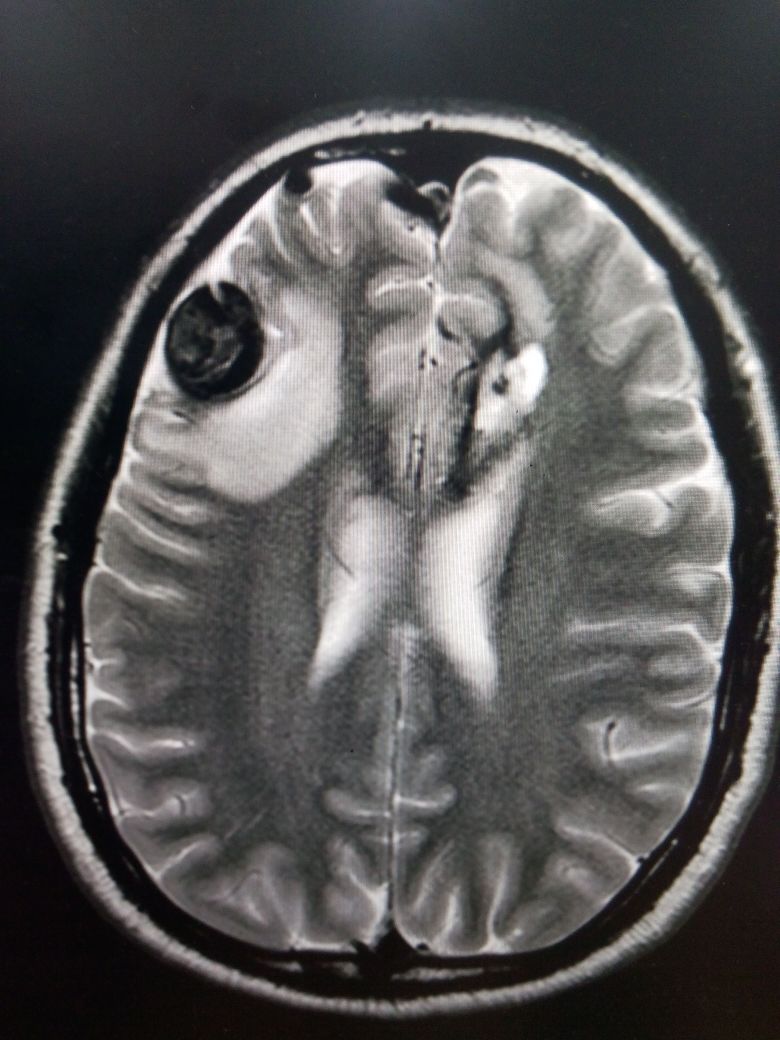

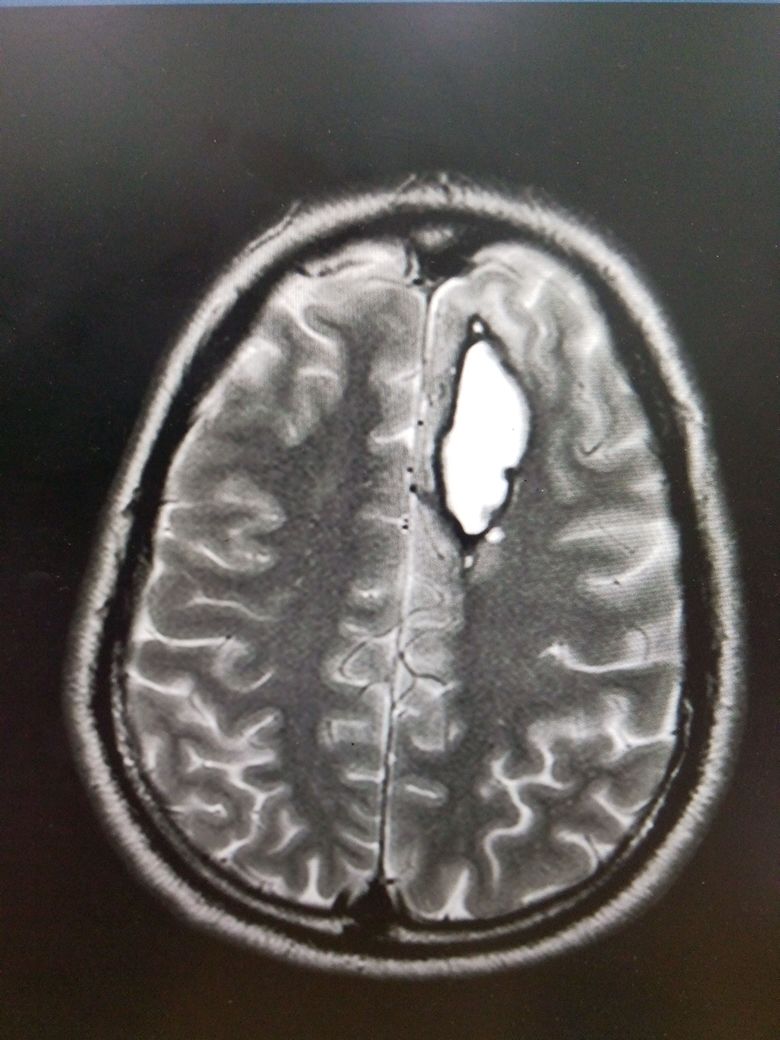

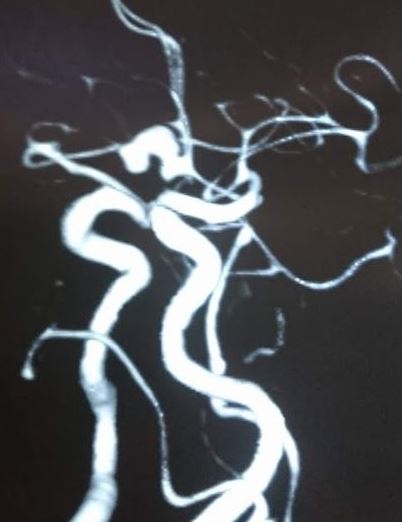

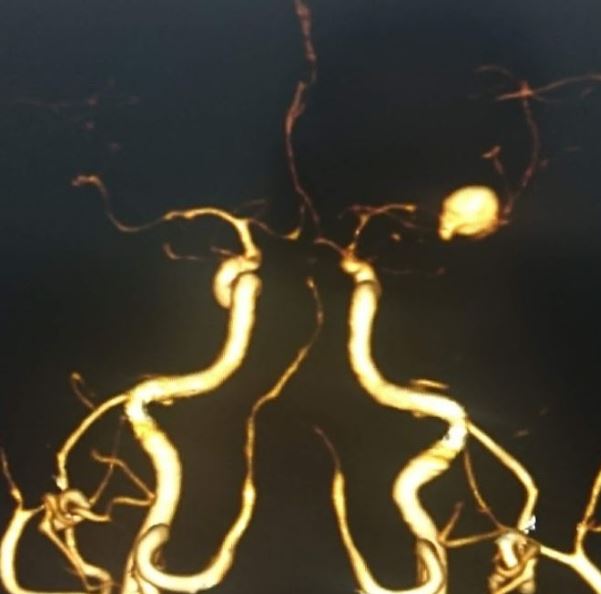

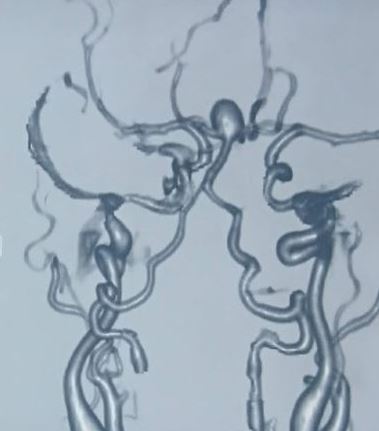

Cerebral aneurysms are defined as dilations that occur at weak points along the arterial circulation within the brain. They can vary in size (small less than 0.5 mm, medium 6 to 25 mm, and large greater than 25 mm). Most are saccular (berry), which is associated with a thin or absent tunica media, and an absent or severely fragmented internal elastic lamina. However, fusiform (circumferential) and mycotic (infectious) aneurysms are present in a small percentage of cases. The majority of cerebral aneurysms are silent and may be found incidentally on neuroimaging or upon autopsy. Approximately 85% of aneurysms are located in the anterior circulation, predominately at junctions or bifurcations along the circle of Willis (see Images. ACom aneurysm, MCA Bifurcation Aneurysm). Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) usually occurs with rupture and is associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Most cerebral aneurysms are acquired lesions, with an increased incidence in patients with certain risk factors such as advanced age, hypertension, smoking, alcohol abuse, and atherosclerosis. Other causes include cocaine use, tumors, trauma, and certain embolic-forming infections like endocarditis. There is also a strong genetic element, with the incidence significantly increased in patients with a strong family history of aneurysms (in other words, more than one family member was affected). Certain genetic conditions are associated with higher prevalence. This includes but is not limited to, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, fibromuscular dysplasia, tuberous sclerosis, arteriovenous malformations (AVM), and coarctation of the aorta (see Image. AVM With Aneurysm and Intraparenchymal Bleeding on MRI).[4]

Epidemiology

The worldwide prevalence of cerebral aneurysms is approximately 3.2%, with a mean age of 50 and an overall 1:1 gender ratio. This ratio changes significantly after age 50, with an increasing female predominance approaching 2:1, thought to be due to decreased circulating estrogen causing a reduction in the collagen content of the vascular tissue. The rate of rupture causing SAH is about 10 per 100,000. This is higher in certain populations such as the Finnish and Japanese. However, this is not due to a higher prevalence of aneurysms in these populations. The overall mortality due to aneurysmal SAH is considered to be 0.4 to 0.6% of all-cause deaths, with an approximate 20% mortality and an additional 30 to 40% morbidity in patients with known rupture.[5]

Pathophysiology

It is believed that a multifactorial process leads to the formation of saccular aneurysms. Hemodynamic stress on the internal elastic lamina causes breakdown over time. This is coupled with vibrations from turbulent blood flow, causing structural fatigue. There is also evidence that T-cell and macrophage-mediated inflammation causes histologic changes within the vascular wall contributing to aneurysmal formation and growth. The process is expedited and amplified in patients with certain risk factors as described previously. Conversely, fusiform aneurysms are predominantly caused by atherosclerosis and mycotic aneurysms from septic emboli present in infectious endocarditis.[6][7]

History and Physical

Unruptured cerebral aneurysms are asymptomatic and are therefore unable to be detected based on history and physical exam alone. However, when ruptured, they commonly present with a sudden onset, severe headache. This is classically described as a “thunderclap headache” or “worse headache of my life.” In 30% of patients, the pain is lateralized to the side of the aneurysm. A headache may be accompanied by a brief loss of consciousness, meningismus, or nausea and vomiting. Seizures are rare, occurring in less than 10% of patients. Sudden death may also occur in 10 to 15% of patients. Interestingly, 30 to 50% of patients with major SAH report a sudden and severe headache 6 to 20 days prior. This is referred to as a “sentinel headache,” which represents a minor hemorrhage or “warning leak.” Physical exam findings may include elevated blood pressure, dilated pupils, visual field and/or cranial nerve deficits, mental status changes such as drowsiness, photophobia, motor or sensory deficits, neck stiffness, and lower back pain with the neck flexion.

The Hunt and Hess grading system can be used by clinicians to predict an outcome based upon initial neurologic status. There are 5 grades, ranging in the severity of symptoms that correlate with the overall rate of mortality. Grade 1 includes a mild headache with slight nuchal rigidity. Grade 2 is given for a severe headache with a stiff neck but without a neurologic deficit other than cranial nerve palsy. For grade 3, the patient is drowsy or confused with a mild focal deficit. In grade 4, the patient is stuporous with moderate to severe hemiparesis. Finally, grade 5 includes a coma with decerebrate posturing.

Evaluation

Most unruptured cerebral aneurysms are identified incidentally when a patient gets neuroimaging for some other reason. However, high-risk individuals may be screened with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomographic angiography (CTA), or conventional angiography (see Image. Aneurysm Formation and Intraparenchymal Bleed on MRI).

In the case of suspected rupture causing SAH, the diagnosis is traditionally made with a non-contrast CT of the brain, with or without a lumbar puncture (LP). CT alone is considered very sensitive for SAH when the patient presents early, but sensitivity declines over time. Some studies suggest that CT is 100% sensitive if performed within 6 hours of the onset of symptoms but drops to 92% within 24 hours and 58% at day 5 (14 to 18).

If CT is negative and there is still clinical suspicion for SAH, then an LP should be performed. The classic findings on LP are an elevated opening pressure and an elevated red blood cell count that does not diminish from tube 1 to tube 4. The presence of xanthochromia, a pink or yellow tint of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) due to hemoglobin breakdown products, is highly suggestive of SAH. Xanthochromia can be identified by visual inspection or by using spectrophotometry and is considered more than 95% sensitive when performed at least 12 hours after onset of bleed.

Once the diagnosis of SAH is made, the source of bleeding should be identified. This can be done using CTA, MRA, or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). DSA consists of inserting a catheter into the arterial circulation and injecting contrast under fluoroscopy. This is considered the “gold standard” for the detection of aneurysmal SAH.[8][1][9]

Treatment / Management

The decision to treat is multifactorial and depends on the size, location, age, and comorbidities of the patient, as well as whether or not there is a rupture. The treatment can be divided into 2 categories: surgical and endovascular. The surgical approach is performed under general anesthesia in the operating room and includes placing a tiny metal clip across the neck of an aneurysm preventing blood from entering the aneurysmal sac, thus eliminating the risk of bleeding. The aneurysm is accessed by temporarily removing a small portion of the skull, dissection of the dura, and separation from other blood vessels using a microscope. The clip is then carefully applied, the skull is secured in place with thin metal plates and screws, and the wound is closed. Over time the aneurysm will shrink and scar; however, the clip will usually remain for life.[10][11] See Image. Basilar Tip Aneurysm.

Endovascular coiling is a less invasive approach that can be used in certain situations. The possible complications include thromboembolism and intraprocedural aneurysm rupture. The procedure is performed by inserting a catheter through the femoral artery and passing it up into the artery containing the aneurysm. Then, a second microcatheter is inserted through the initial catheter, which contains the platinum coil. Electric current is used to detach the coil from the catheter within the lumen of the aneurysm. This promotes local clot formation and obliteration of the aneurysmal sac.

In the case of rupture, management also includes treating complications associated with SAH. This usually occurs within an intensive care unit (ICU) setting to monitor for signs of clinical deterioration caused by rebleeding, symptomatic vasospasm, hydrocephalus, seizures, and hyponatremia. Nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker, is frequently used to prevent cerebral ischemia due to vasospasm following SAH.

Differential Diagnosis

- Arteriovenous malformations

- Cavernous sinus syndromes

- Carotid/vertebral artery dissection

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Migraine and cluster headaches

- Moyamoya disease

- Pituitary apoplexy

- Stroke - ischemic or hemorrhagic

- Vein of Galen malformation

Prognosis

Once a cerebral aneurysm ruptures, morbidity and mortality are very high. Nearly 25 % are dead within the first 24 hours, and 50% will die within the next three months.[12][13] [Level 5] Even in the following treatment, there is a high mortality rate of nearly 40%. The prognosis is also dependent on the following factors:

-

Age

-

Location of an aneurysm

-

Degree of vasospasm

-

Presence of hypertension and other comorbidities

-

Neurological status on admission

-

The extent of intraventricular hemorrhage

Complications

- Recurrent bleeding

- Vasospasm

- Seizures

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

- Hydrocephalus

- Arrhythmias. congestive cardiac failure

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Neurogenic pulmonary edema

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

- After discharge, most patients require physical, speech, and occupational therapy.

- Patients also need to be prophylaxes against deep venous thrombosis, urinary tract infections, and seizures.

- Serial imaging is also done to ensure that the aneurysm has been obliterated.

Consultations

- Neurosurgeon

- Neurologist

- Interventional neuroradiologist

- Critical care specialist

- Rehabilitation consultant

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education about cerebral aneurysms is critical as 10% die before even reaching the emergency department.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Unruptured cerebral aneurysms are detected more than ever before, primarily because of the more frequent use of modern imaging tools. The biggest risk of cerebral aneurysm is the risk of rupture and severe consequences. The majority of patients have no idea that they have an intracranial aneurysm and most often present with a bleed in the brain. Because of the extremely high mortality, it is important to have a systemic approach to these aneurysms once they are detected.[14] [Level 5] There is expert evidence that the earlier the patient is referred to a neurosurgeon or an interventional neuroradiologist, the outcomes are better than if the patient presents with a rupture. For the most part, unruptured aneurysms are managed with clips or coils when possible. However, there are no randomized trials to compare the different treatments. Without any solid evidence, it is difficult to define a strategy. Experts agree that an interprofessional approach is vital and has to take into account patient comorbidity, location of the aneurysm, and type of endovascular treatment recommended. [Level E]. The nurse should educate the patient on compliance with follow-up once an intracranial aneurysm has been detected. The pharmacist should counsel the patient on discontinuing smoking and remaining compliant with blood pressure medications.

Screening

There continue to be debates about screening for cerebral aneurysms because of the expense. Further, there is a significant debate on the ideal management of a small intracranial aneurysm. Most experts agree that once an aneurysm reaches 7 mm or more, treatment should be undertaken. [Level E]