Introduction

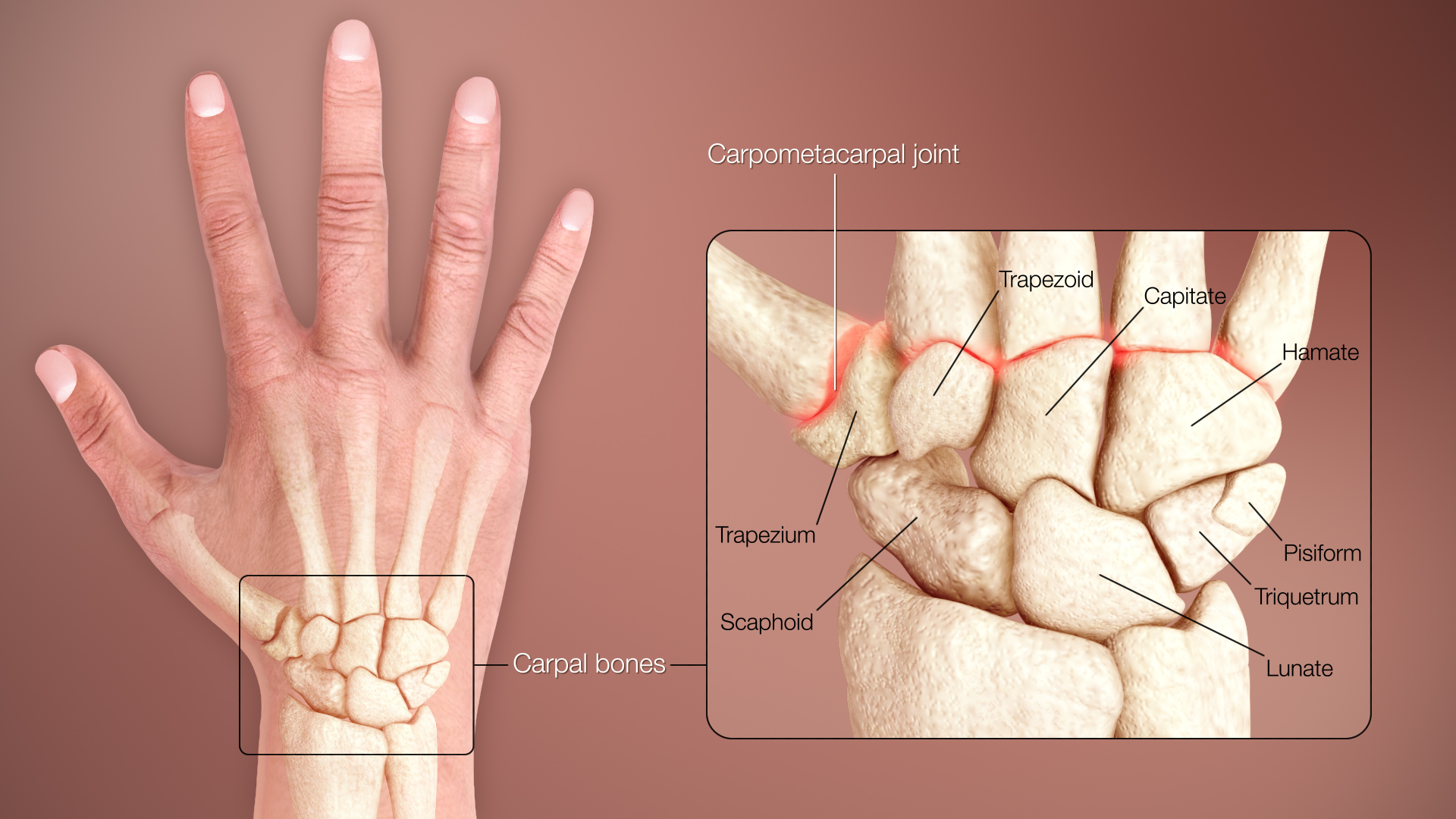

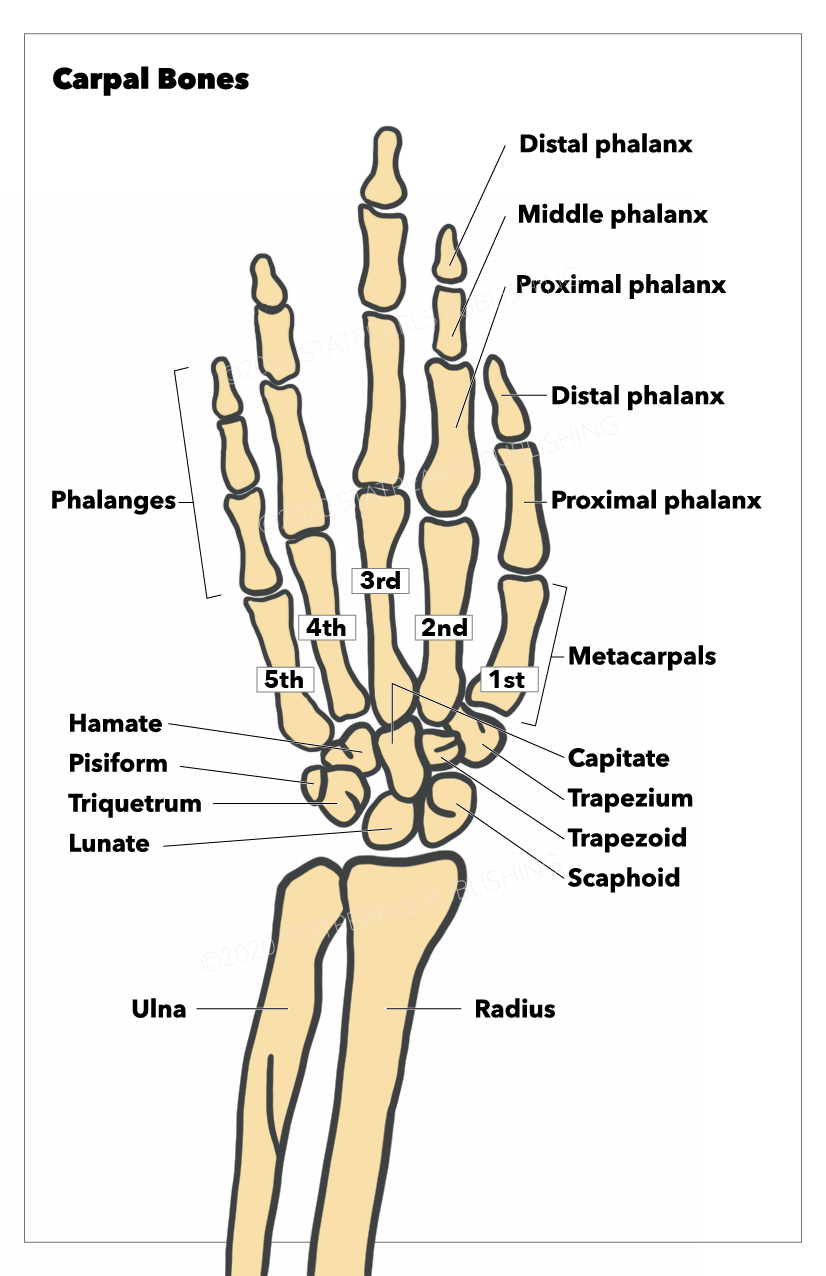

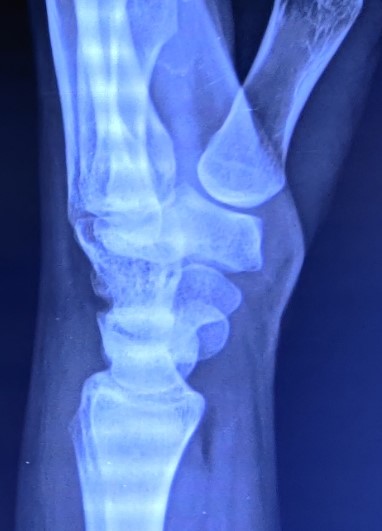

The carpal bones are bones of the wrist that connect the distal aspects of the radial and ulnar bones of the forearm to the bases of the 5 metacarpal bones of the hand (see Image. Normal Posteroanterior Radiograph of the Wrist Joint). Eight carpal bones divide into 2 rows: proximal and distal rows (see Image. Normal Lateral Radiograph of the Wrist Joint). The proximal row of carpal bones (moving from radial to ulnar) are the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform, while the distal row of carpal bones (also from radial to ulnar) comprises the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate. These bones make up most of the skeletal framework of the wrist and allow different neurovascular structures and tendons that enter the wrist to reach certain muscle groups and bony structures, respectively, and provide the innervation and blood supply necessary for them to function (see Image. Left Hand, Anterior View).

Structure and Function

Each carpal bone has unique features that contribute to a specific function in the wrist (see Image. Carpal Bones). Starting from the proximal row, the scaphoid, named for its boat-like appearance, forms the radial border of the proximal carpal row. Most of the surface of the scaphoid is covered by articular cartilage, which allows it to bridge the joint between the 2 rows of carpal bones. The lunate, described for its crescent shape, is located between the scaphoid and the triquetrum and lies near the median nerve. The triquetrum is a pyramid-shaped bone that articulates with the pisiform, lunate, and hamate bones. Last, the pisiform is a pea-shaped bone that articulates with the triquetrum on its dorsal surface and is an attachment site for various tendons and ligaments.[1]

Moving next to the distal row, the trapezium sits between the scaphoid and the base of the first metacarpal bone. It has a saddle-shaped facet for articulation with the first metacarpal and provides a site for a few tendons and ligaments to either pass through or attach. The trapezoid is the smallest carpal bone between the trapezium and the capitate. Conversely, the capitate is the largest and most central carpal bone, articulating several bones and attaching to several intercarpal ligaments. Last, the hamate, named for its hook-like hamulus, forms the ulnar border of the distal carpal row that protects the ulnar artery and nerve within Guyon's canal and provides attachments to several ligaments.[1]

In general, the bones of the hand find their arrangement in 3 arches: 1 longitudinal arch, spanning the hand lengthwise, and 2 transverse arches, 1 at the level of the metacarpal head and the second transverse arch at the level of the carpus (see Image. 3D Medical Illustration of the Wrist Bones of the Human Body). This anatomy mechanically contributes to the hand's ability to grasp objects. In particular, the arrangement of the carpal bones in a transverse arch makes up the floor of the carpal tunnel and provides support and protection to the finger flexor tendons and the median nerve. Moreover, the scaphoid and trapezium both have prominent tubercles projecting anteriorly that not only contribute significantly to the bony anatomy of the carpal tunnel but also provide a supporting base for the thumb to allow it to oppose the rest of the hand and, thus, further enhance the hand’s ability to grasp objects.[1]

Embryology

Upper limb development initiates with activating a group of mesenchymal cells in the lateral mesoderm towards the end of the fourth week, with the limb buds becoming visible around day 26 or day 27. Each limb bud comprises a mass of mesenchyme covered by ectoderm. This mesenchyme remains undifferentiated until it is ready to develop into bone, cartilage, and blood vessels later in development. Meanwhile, at the apex of each limb bud, the ectoderm thickens to form the apical ectodermal ridge, which stimulates the growth and development of the upper limb bud in the proximal-distal axis. Other signaling centers and primary morphogens, such as the zone of polarizing activity, derived from an aggregate of mesenchymal cells in the limb bud, and the Wnt pathway, expressed from the dorsal epidermis of the limb bud, also contribute to the development of the upper limb buds by regulating growth along the anteroposterior axis and the dorsoventral axis, respectively.[2]

At the end of the sixth week of development, digital rays form in the hand plate. By the seventh week, the carpal chondrification process begins. The capitate and the hamate carpal bones are the first chondrogenic centers to appear as immature cartilage early in the eighth week, while the pisiform is the last to appear later in the eighth week. The hamulus, otherwise known as the “hook of the hamate,” also appears as an immature cartilaginous tissue towards the end of the eighth week and does not develop until the thirteenth week. Last, in the fourteenth week, a vascular bud penetrates the lunate cartilage mold, an early sign of the osteogenic process that is completed during the first year of life.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The radial artery, ulnar artery, and anastomoses provide the blood supply of the wrist. The radial artery predominantly supplies the thumb and the lateral side of the index finger, while the ulnar artery supplies the rest of the digits and the medial side of the index finger. In particular, vascular supply occurs via the anastomotic network consisting of 3 dorsal and 3 palmar arches, which arise from both the radial and ulnar arteries that overlie the carpal bones.[4] The scaphoid, capitate, and a small proportion of lunates (20%) have 1 intraosseous vessel supply. Of note, the scaphoid has a single blood supply from the radial artery that enters from the distal portion of the bone to supply the proximal portion, thus making its proximal pole most vulnerable to avascular necrosis. The trapezoid and hamate both have 2 blood supply areas without intraosseous anastomoses. The trapezium, triquetrum, pisiform, and most lunates (80%) have 2 areas of blood supply and consistent intraosseous anastomoses. Therefore, the rest of the carpal bones, excluding the scaphoid, capitate, and a small proportion of lunates, have a lower risk of developing avascular necrosis following a fracture.[5]

Nerves

Innervation of the wrist joint comes from the following:

- anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve

- posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve

- the dorsal and the deep branches of the ulnar nerve

The lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, the posterior interosseous nerve, the dorsal branch, the ulnar nerve's perforating branches, and the radial nerve's superficial branch innervate the wrist joint from the dorsum. The palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, the anterior interosseous nerve, and the main trunk and deep branch of the ulnar nerve innervate the wrist joint from the palmar side.[6]

Muscles

Two types of muscles make up the muscles of the hand: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic muscles have muscle bellies within the forearm and tendons that enter the wrist. They enhance wrist stability by keeping the hand placed into the concave radial surface during co-contraction. Intrinsic muscles originate within the hand and contribute to wrist stability by balancing flexor and extensor forces through their attachment to metacarpal bases.[1]

Some carpal bones serve as sites of origin or as sites of insertion for the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the hand. The flexor carpi ulnaris is the only extrinsic muscle that inserts onto carpal bones, specifically the pisiform and hook of the hamate and the base of the fifth metacarpal bone, which allows it to flex and adduct the wrist joint. All the intrinsic muscles have their origin sites on the carpal bones. The thenar muscles, which include the opponens pollicis, abductor pollicis brevis, and flexor pollicis brevis, have origin sites that involve the prominent tubercles of the scaphoid and trapezium. The adductor pollicis originates from the capitate and the second and third metacarpal bones. Last, the hypothenar muscles, such as the abductor digiti minimi, flexor digiti minimi brevis, and opponens digiti minimi, originate from the pisiform and hook of the hamate.[7]

Physiologic Variants

Although uncommon, the number of carpal bones may vary in the presence of accessory bones, split bones, anatomical variants, or congenital anomalies. Reports exist of over twenty accessory carpal bones, with the most common variants being the os centrale carpi, the os radiale externum, the triangular bone, and the styloideum bone. Other cases of additional carpal bones may involve split bones of the scaphoid, lunate, and even the hamate. Anatomical variants causing extra carpal bones arise due to a failure of fusion from carpal bone ossification centers. Last, congenital anomalies causing fewer carpal bones can occur either due to congenital absence of normal bone (which mainly occurs with the scaphoid, lunate, or triquetrum) or from a coalition between 2 carpal bones, which most commonly involves the lunate and triquetrum.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Surgical approaches to the carpus can be divided into general and specific carpal exposures. General exposures, done either from a dorsal or volar approach, provide broad exposure to large areas of the wrist and allow surgeons access to pathology involving multiple joints or carpal bones. Specific exposures provide limited exposure and permit access to a single bone, most commonly the scaphoid or joint, for situations where the diagnosis is clear and management is precise.[9]

Surgical approaches to the hand and wrist require meticulous care because of the proximity between the deep structures of the hand and the carpus. Close attention to the anatomical relationship between important ligaments, tendons, nerves, and blood vessels begins with the initial skin incision. The design of the incision must consider the intimacy between these structures to avoid damage to integral components of the hand and wrist. These include the sensory nerves to the hand that make up much of the sensory homunculus, the creases of the skin to prevent contracture, the blood supply to the skin or skin flaps for primary wound healing, and even the hand's cosmetics for the patient's sake.[9]

Clinical Significance

Athletes commonly incur injuries to the hand or wrist; reports indicate that sporting activities account for approximately 22% of all hand fractures in adults. Of all hand fractures in adults, carpal fractures are the least common (12%) compared to metacarpal fractures (34%) and phalangeal fractures (54%).[10] Among carpal fractures, the most commonly injured carpal bone is the scaphoid. There is a high incidence of scaphoid fractures in college football players and an increasing incidence in female athletes.[11] Upon falling on an outstretched hand (FOOSH injury), the scaphoid receives most of the force transmitted from the radius due to its size and anatomic location. Of importance, the proximal pole of the scaphoid bone is highly susceptible to avascular necrosis following fractures across the waist of the scaphoid due to its limited blood supply and poor collateral circulation.[1][5]

Scaphoid fractures commonly present with radial-sided wrist pain and tenderness in the anatomical snuffbox, on axial loading of the thumb, and during pincer grasp. They are generally diagnosed with radiographic imaging but may require a CT scan to identify the fracture configuration. However, in specific cases, non-displaced fractures can be missed due to subtle fracture lines or even the irregular contour of the bone. MRI or bone scintigraphy may be used to confirm the diagnosis in these cases.[11]

Treatment of scaphoid fractures depends on their location and whether bone displacement has occurred. Distal pole scaphoid fractures can be treated conservatively, whereas proximal pole fractures must undergo surgical repair. Displaced fractures have an increased risk of nonunion and thus require surgery with headless compression screw fixation, which offers the fastest recovery and a return to sports. Management of non-displaced fractures is with cast immobilization.[11]

Other carpal injuries include hook of the hamate fractures and lunate dislocation:

Hook of the Hamate Fracture

- These fractures are caused by direct blows, usually from "grounding" a golf club or "checking" a baseball bat. They typically present with hypothenar pain and paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution. They are diagnosed with radiographic imaging and confirmed with a CT scan if initial x-ray findings are negative. The current standard of care remains to excise the hook of the hamate fragment, which has produced successful results with a return to sports in 6 weeks.[11]

Lunate Dislocation

- Due to the lunate’s proximity to the median nerve, anterior displacement of the bone may cause mechanical compression of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel and produce signs and symptoms consistent with median nerve neuropathy, such as paresthesias of the first 3 digits and radial half of the fourth digit and weakness and atrophy of the thenar eminence.[12]

Besides, the anatomic relationship of the carpal bones can also get disturbed by ligament injuries, producing 2 types of instabilities: dorsal intercalated segmental instability (DISI) and volar intercalated segmental instability (VISI).[13]