Introduction

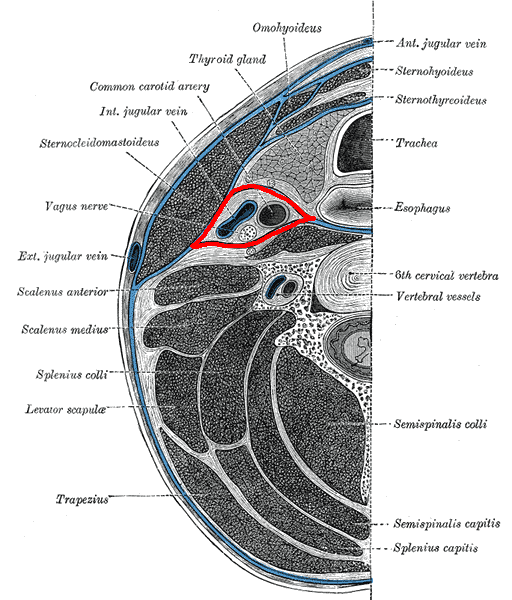

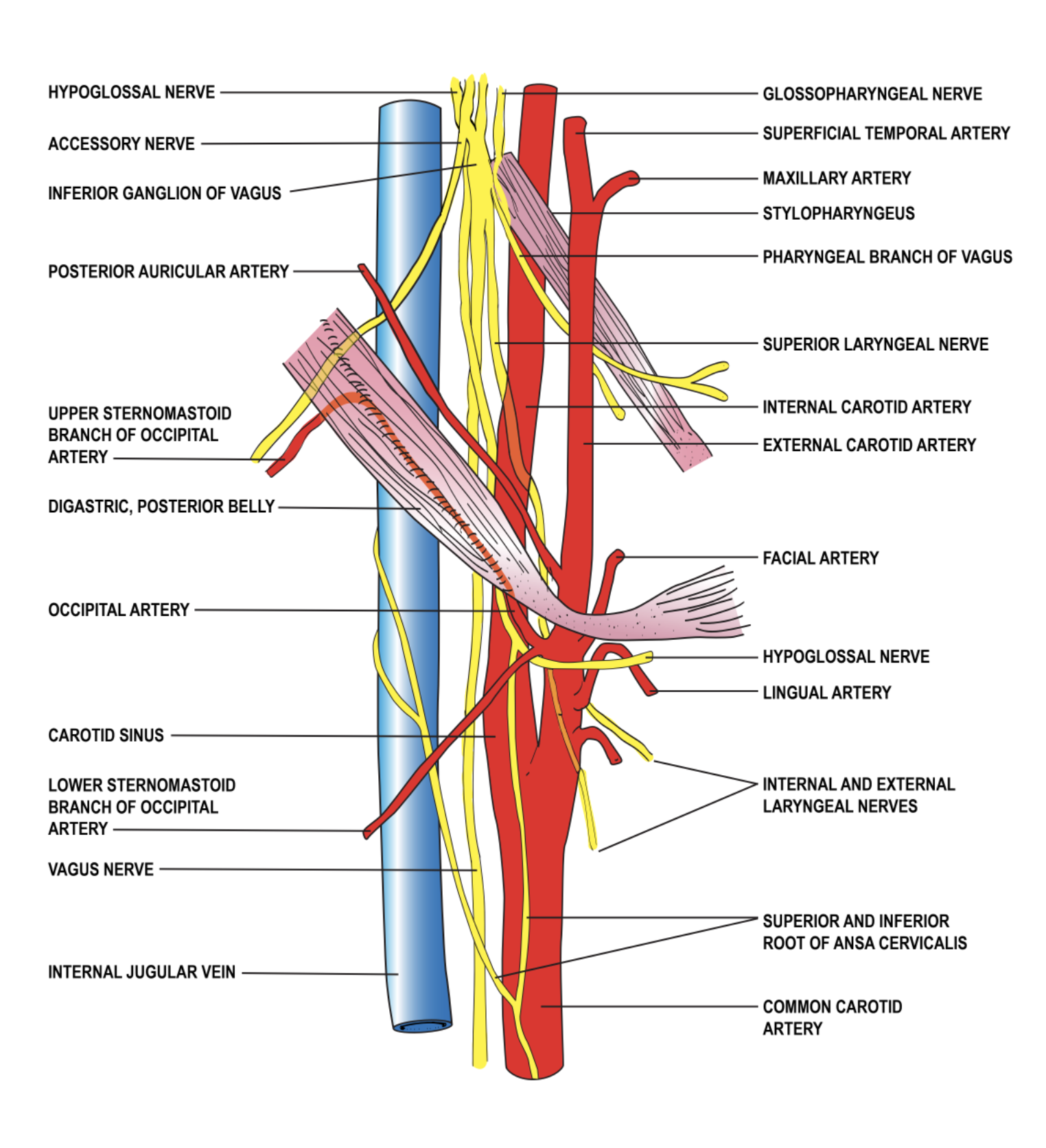

The carotid sheath is an important landmark in head and neck anatomy and contains several vital neurovascular structures, including the carotid artery, jugular vein, vagus nerve, and sympathetic plexus (see Image. Carotid Sheath). It extends upwards from the arch of the aorta and terminates at the skull base. While the carotid sheath itself is rarely the source of primary disease, understanding its anatomy is essential for clinicians to address problems that may affect the crucial neurovascular structures that travel through it. See Image. Anatomy of the Carotid Sheath.

Structure and Function

The function of the carotid sheath is to separate and help protect the vital structures within it. It facilitates the passage of intrathoracic structures through the neck to terminate in the head and face. It is a fibrous connective tissue sheath encircling several key structures within the neck.[1] These structures include:

- Common carotid artery

- Internal carotid artery

- Internal jugular vein

- Glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX)

- Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X)

- Accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI)

- Hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII)

- Sympathetic plexus of nerves

- Deep cervical lymph nodes

The carotid sheath is located posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and is a part of the deep cervical fascia of the neck. Superiorly, the carotid sheath encircles the margins of the carotid canal and the jugular fossa at the skull base. From here, it extends downwards, terminating at the aortic arch. It is divided in the craniocaudal direction into two regions, the suprahyoid and infrahyoid spaces, the boundary between which is the bifurcation of the common carotid artery.[2]

The immediate relations of the carotid sheath are the pharynx medially, the parotid gland laterally (in the suprahyoid region), the infratemporal fossa anteriorly (in the suprahyoid region), and the prevertebral fascia posteriorly.

Embryology

The carotid sheath, like other fascial tissues, is derived from mesoderm. The adventitia of the cervical great arteries becomes apparent by 15 weeks gestation and is one of the earliest components of the fetal deep cervical fascia.[3][4] The carotid sheath does not appear until approximately 20 weeks gestation. At this time, it is fused with the pretracheal fascia but not yet integrated into the prevertebral lamina of the deep cervical fascia.[5][6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The two vascular structures within the carotid sheath are the common carotid artery, which becomes the external carotid artery, and the internal jugular vein.

At the base of the carotid sheath, the common carotid artery arises on the left side from the arch of the aorta directly and on the right side from the brachiocephalic trunk. Proximal to its bifurcation, there are no branches from the common carotid artery. The bifurcation of the common carotid artery commonly occurs at the level of the thyroid cartilage (C4 level).

The external carotid artery exits the carotid sheath at this point to travel within the parotid gland. The internal carotid artery continues within the sheath and is initially bulbous as it contains within its arterial wall the carotid sinus, a baroreceptor regulating blood pressure. The carotid body is a separate structure situated behind the bifurcation. This chemoreceptor is primarily receptive to changes in oxygen partial pressures and is thus involved in respiratory reflexes. The glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves innervate both the carotid sinus and the carotid body. The common carotid artery gives off no branches of its own and enters the skull base through the carotid canal in the anteromedial part of the temporal bone.[7]

The internal jugular vein is a continuation of the sigmoid sinus and begins its descent towards the heart at the jugular foramen, running with the vagus nerve. It travels within the carotid sheath, lateral to the internal carotid and common carotid arteries in its descent, draining into the subclavian vein, ultimately forming the brachiocephalic vein. While moving posteriorly, the internal jugular vein receives venous blood from the facial, lingual, superior thyroid, and middle thyroid veins.

Deep cervical lymph nodes are also contained within the carotid sheath; specifically, those within levels II (upper internal jugular), III (middle internal jugular), and IV (lower internal jugular) of the neck, comprising together the group of nodes termed the deep cervical chain.[8]

Nerves

The nerves that travel within the carotid sheath are the vagus, hypoglossal, and accessory cranial nerves, as well as branches of the ansa cervicalis and sympathetic nerves.

Vagus Nerve

The vagus nerve (CN X) has the longest course of any cranial nerve, beginning by passing through the middle part of the jugular foramen with the internal jugular vein and descending within the carotid sheath. It runs posteriorly and between the carotid artery (initially internal, then common) and the internal jugular vein.[9]

Within the neck, the vagus nerve gives off the pharyngeal branch and the superior laryngeal nerve. The pharyngeal branch supplies motor fibers to the pharyngeal muscles except for the stylopharyngeus. Lesions affecting the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve cause deviation of the uvula to the side opposite the injury. The superior laryngeal nerve divides into the internal and external laryngeal nerves. These nerves supply sensory fibers to the larynx above the vocal cord, the lower pharynx, and the epiglottis, and supply taste fibers to the root of the tongue near the epiglottis.

Passing into the mediastinum at the root of the neck, the vagus nerve travels anteriorly over the subclavian artery to supply the thoracic and abdominal viscera.

Glossopharyngeal Nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) descends from the anterior part of the jugular foramen, running within the carotid sheath at the lateral aspect of the carotid artery.[10] It then exits the carotid sheath along the lateral border of the stylopharyngeus muscle (supplying it with a motor branch), behind the external carotid artery, before coursing forward towards the tongue and branching further into pharyngeal, tonsillar, and lingual branches.

Accessory Nerve

The accessory nerve (CN XI) exits the skull base in the middle part of the jugular foramen, sharing a meningeal sleeve with the vagus nerve. It travels in the suprahyoid region of the carotid sheath briefly anteriorly to the internal jugular vein, continuing laterally and exiting the sheath.

Hypoglossal Nerve

The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) exits the skull base through the hypoglossal canal and descends initially in the carotid sheath posteriorly to the vagus nerve. It then exits the carotid sheath by emerging between the internal carotid artery and the internal jugular vein before traveling on the anterior aspect of the outside of the sheath, deep to the styloid muscles.

In addition, the ansa cervicalis is embedded in the anterior portion of the carotid sheath.

Muscles

As previously stated, the carotid sheath is derived from all three layers of the deep cervical fascia. While there are no muscles within the carotid sheath, there are muscles whose relation to the carotid sheath provides valuable landmarks.

The sternocleidomastoid muscle forms the anterolateral boundary of the carotid sheath.

In the suprahyoid section of the carotid sheath, the stylopharyngeus muscle lies obliquely over the internal carotid artery, and its inferior border is closely associated with the glossopharyngeal nerve as it leaves the sheath.

Similarly, inferior to the stylopharyngeus muscle in the suprahyoid region of the carotid sheath, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle lies obliquely over the internal jugular vein and internal carotid artery close to the bifurcation of the common carotid artery [11]. The accessory nerve passes under this muscle as it exits the sheath.

Physiologic Variants

There are no significant physiologic or anatomic variants of the carotid sheath itself; it can be disrupted or lay in an unusual fascial plane if the common carotid arteries have an atypical course through the neck. Carotid variations are common (i.e., the right common carotid branching off the aorta directly.)[12][7] Furthermore, the extracranial course of the cranial nerves traveling in the carotid sheath has significant inter-individual variability, which can provide difficulty when operating within the region [10][11]. Thus, access to the contents of the carotid sheath should be performed with care and can be done with the aid of ultrasound or other imaging if an anatomic variation is suspected.

Surgical Considerations

Carotid Endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy is performed to excise atherosclerotic thickening of the intima within the internal carotid artery in an effort to reduce strokes in patients with significant carotid artery stenosis (typically greater than 70 to 80% stenosis +/- symptoms). The opening incision is made, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle is retracted. At this point, it is important to visualize the carotid sheath, for this is where the structure vital to the procedure is located. The carotid artery lies on the medial side of the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve is situated posteriorly. Superiorly, the carotid sheath may also contain the hypoglossal nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the accessory nerve. These structures pass horizontally and cross the internal carotid artery. It is important to identify these structures before incising any structure. The surgeon opens the carotid sheath to gain exposure to the common carotid bifurcation, as this is the most common site for atherosclerosis due to non-laminar blood flow. Once access is gained to the carotid sheath, and the carotid bifurcation is located, the surgeon removes any atherosclerotic plaque and repairs the vessel. Possible complications include air embolism and laceration of the internal jugular vein or carotid artery.[13][14][15]

Penetrating Neck Trauma

An ongoing debate among trauma surgeons is over a no-zone approach, which leans heavily on multidetector CT angiography versus a zoned approach to surgical exploration.[16][17]

Zones of the Neck

The neck is divided into three zones. These become important when assessing and managing trauma in those with penetrating neck injuries.

Zone I - cricoid cartilage to the sternal notch: trachea, lung, esophagus, thoracic duct, vertebral arteries, the origin of the common carotid artery, and subclavian vessels, spinal cord, thoracic duct, thyroid gland

Zone II - cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible: carotid sheath and its components (carotid artery, internal jugular vein, vagus nerve), trachea, esophagus, spinal cord, larynx, pharynx

Zone III - the angle of the mandible to the base of the skull: distal portion of internal carotid artery, vertebral arteries, jugular veins, pharynx, spinal cord, sympathetic chain, CN IX, X, XI, XII

The decision to surgically explore these areas is based on hard and soft signs. Regardless of the zone, surgical exploration is the best course of management if the patient becomes unstable.

Soft Signs

- History of arterial bleeding

- Tracheal deviation

- Nonexpanding large hematoma

- Apical capping on chest radiograph

- Stridor

- Hoarseness

- Vocal cord paralysis

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) injury

- Unexplained bradycardia (without CNS injury)

Hard Signs

- Hypotension

- Active arterial bleeding

- Diminished carotid pulse

- Expanding hematoma

- Audible bruit or palpable thrill

- Neurologic deficit

- Hemothorax greater than 1000 mL

- Air bubbling of wound

- Hemoptysis

- Hematemesis

If the patient presents with hard signs, then emergent management is needed (i.e., airway and circulation management, immediate decompression, and repair of the injured vessel). If soft signs are present, then serial physical examination and non-emergent imaging may be appropriate.

Clinical Significance

Internal Jugular Central Venous Line

Placement of an internal jugular central venous line is performed to gain vascular access, enabling both venous monitoring and administration of medications and fluid resuscitation. The procedure begins by placing the patient in slight Trendelenburg and locating the internal jugular vein within the apex of the triangular interval between the clavicular and sternal heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It may help to have the patient turn the head to the contralateral side to better visualize these anatomical landmarks. If the patient is conscious, begin by applying a local anesthetic. Next, insert the needle at a 45-degree angle posteriorly while applying negative pressure. The needle will pass through the carotid sheath, and the internal jugular vein will produce blood within the syringe. An ultrasound can help assist with visualization and cannulation and ensure the proper placement of the guide needle into the vein. While keeping the guide needle in place, begin threading the guidewire. Once in place, remove the needle, introduce the dilator, and then the catheter. The catheter should now be within the superior vena cava.[18]

It is essential to understand the relationships of the structures within the carotid sheath to perform an internal central venous line insertion properly.

Carotid Body Tumor

Carotid body tumors are typically slow-growing, painless masses found most commonly in the fourth and fifth decades.[8] These tumors may present with lower cranial nerve signs given the anatomical relationship of the carotid body within the sheath to these nerves. Although the pathogenesis of these tumors is unclear, they are paragangliomas arising from the neural tissue in the carotid body. Surgical removal is recommended; this involves ligation and bypass of the carotid artery bypass and, as such, is a high-risk procedure.[19]

Lemierre Syndrome

Lemierre Syndrome, a suppurative jugular thrombophlebitis, is a serious sequela of odontogenic or oropharyngeal infection. Infection typically spreads from the lateral pharyngeal space to the carotid sheath, where it can seed the internal jugular vein, precipitate septicemia, generate septic emboli, and erode the carotid artery. It is typically due to Fusobacterium or Bacteroides species. While it is uncommon in the antibiotic era, patients with poor dental hygiene and limited access to the healthcare system are still at risk. [20]

Other Issues

The carotid sheath should not be confused with the carotid space or the carotid triangle. The carotid space is the anatomic area that the sheath encloses, while the carotid triangle is a specific portion of the anterior aspect of the neck through which the carotid sheath passes.