Introduction

The intricacy of the coronary venous system highlights both the complexity and beauty of the human heart's anatomical features. As biomedical science and technology advance, coronary veins have gained significant clinical importance for treatment and intervention for cardiac patients globally. Coronary veins are responsible for draining deoxygenated blood from the myocardium into the cardiac chambers. Comprised of two venous systems, coronary veins classify into either the greater cardiac venous system or the smaller cardiac venous system. The greater cardiac venous system drains the majority of the deoxygenated blood, while the smaller cardiac venous system drains a smaller portion of the deoxygenated blood to its respective heart chambers. Physiological variability of coronary veins also exists among a diverse patient population. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the anatomy of the coronary venous vasculature is thus vital to enhance clinical knowledge and aid informed physician decision-making for future cardiovascular patients.

Structure and Function

The primary physiological function of the coronary veins is to carry deoxygenated blood from the myocardium and empty them into the chambers of the heart. Coronary veins can be organized into two groups: the greater and smaller cardiac venous system.

Greater Cardiac Venous System

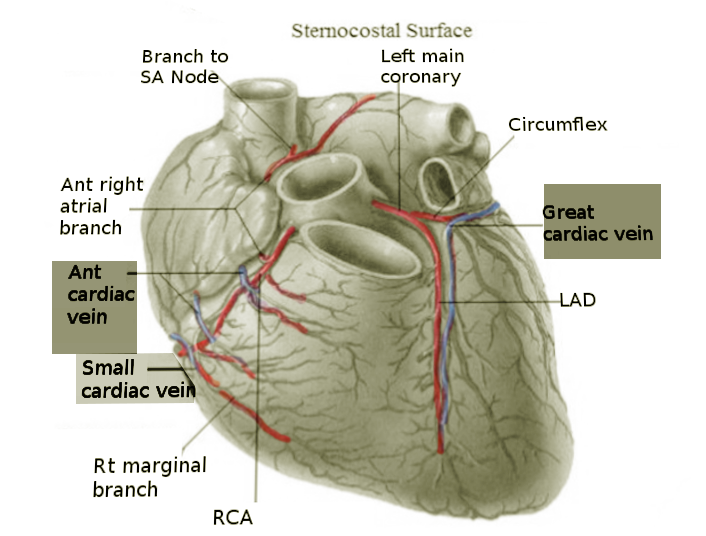

The greater cardiac venous system returns three-quarters of the deoxygenated blood from the myocardium to the cardiac chambers. The main venous vasculature of this system includes the coronary sinus and its tributaries, marginal veins, anterior cardiac veins, ventricular veins, and atrial veins.[1][2]

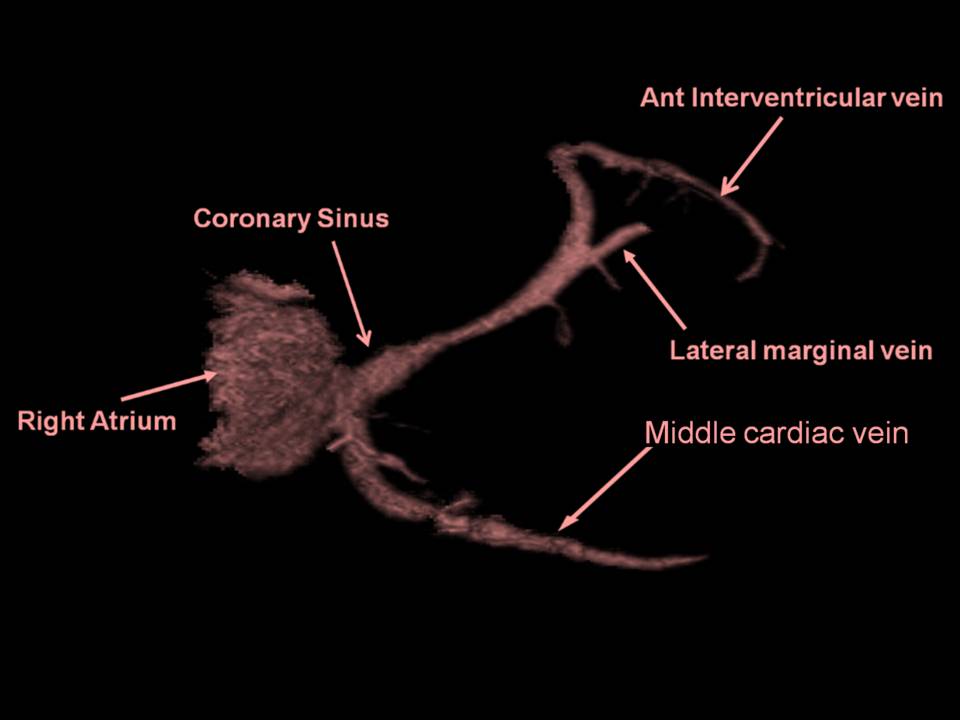

Coronary Sinus

The coronary sinus is the largest cardiac vein with multiple smaller vessels converging into it. Located along the left posterior atrioventricular groove, the coronary sinus empties directly into the right atrium through the coronary sinus orifice. The venous tributaries that merge into the coronary sinus include the great cardiac vein, middle cardiac vein, small cardiac vein, left posterior ventricular, and oblique cardiac vein.[2][3]

Great Cardiac Vein

Starting from the apex of the heart and running parallel with the anterior interventricular artery, the great cardiac vein travels up along the anterior interventricular sulcus towards the base of the left atrium’s auricle[2]. Once the vein reaches the left margin of the heart, it circumvents to the posterior side and eventually converges with the oblique vein of the left atrium into the coronary sinus. The great cardiac vein empties the blood from both ventricles and the left atrium into the right atrium.[3][4]

Middle Cardiac Vein

The middle cardiac vein originates from the apex of the heart but on the posterior side. The middle cardiac vein travels alongside the posterior interventricular artery in the posterior interventricular sulcus, and empties deoxygenated blood into the coronary sinus.[3]

Small Cardiac Vein

Located in the coronary sulcus between the right atrium and right ventricle, the small cardiac vein eventually coalesces with the coronary sinus on the posterior side of the heart and drains to the right atrium.[3] The small cardiac vein also runs parallel to the right marginal branch of the right coronary artery on the anterior surface of the heart and collects deoxygenated blood from the posterior side of the right chambers.[5]

Right Marginal Vein

The right marginal vein is located on the very inferior margin of the anterior surface of the heart and serves to empty the anterior and diaphragmatic walls of the right ventricle.[3] This small vein is also known for merging with the small cardiac vein in the coronary sulcus.[5]

Anterior Cardiac Veins

Anterior cardiac veins return blood from the anterior right ventricle and drain them directly into the anterior right atrium. The anterior cardiac veins are more superior to the right marginal vein.[4]

Left Marginal Vein

Also known as the obtuse marginal vein, the left marginal vein drains the myocardium of the left ventricle.[2] This vein travels along the left oblique marginal surface of the heart.

Left and Right Ventricular Veins

The left and right ventricular veins vary from person to person, but generally, they function to drain the external walls of the ventricles[6].

Left and Right Atrial Veins

The left atrial veins consist of the septal veins, posterolateral veins, and posterosuperior veins that all carry the deoxygenated blood from the left atrium into the right atrium. The right atrial veins drain the right atrial walls.[7]

Inferior Vein of the Left Ventricle

Also known as the posterior vein of the left ventricle, the inferior left ventricular vein returns the deoxygenated blood from the inferior and lateral walls of the left ventricle into the coronary sinus. This vein travels between the middle and great cardiac veins.[5]

Oblique Vein of the Left Atrium

The oblique vein of the left atrium is a relatively small-sized vein that rounds obliquely and inferiorly towards the posterior left atrium. The vein is also observed to unite with the great cardiac vein to merge with the distal coronary sinus.[4]

Smaller Cardiac Venous System

The smaller cardiac venous system returns one-quarter of the deoxygenated blood from the inner layers of the myocardium to the cardiac chambers. This system is mainly composed of Thebesian veins draining deoxygenated blood from all sections of the myocardium chambers. Thebesian veins also drain the right side of the heart more than the left side.[8]

Embryology

During embryo development, the angiogenesis of coronary veins begins from the sinus venosus, an embryonic vein that returns blood to the heart[9] The venous endothelial cells from the sinus venosus migrate towards the surface of the myocardium and then differentiate into coronary veins and their tributaries.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Coronary veins receive oxygenated blood and nourishment from coronary arteries and their tributaries. Additionally, large veins especially receive nutrient-rich blood supply from the vasa vasorum, a network of microvessels. Vasa vasorum are also known as the vessels of the vessels.[10]

Nerves

The heart and its venous vasculature engage in autonomic innervation. Located in the brainstem, the medulla plays a significant role in regulating the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves to the heart and its blood vessels. In the sympathetic division, the sympathetic nerves exit the medulla and synapse with preganglionic fibers in the upper thoracic spinal cord. The preganglionic fibers then synapse with postganglionic fibers in the sympathetic ganglia, where the postganglionic nerves finally travel to and synapse with the target sites in the heart and coronary veins.[11] In the parasympathetic division, the preganglionic efferent fibers of the vagus nerve exit the medulla and synapse with postganglionic fibers within the vascular venous tissue.[12] Overall, sympathetic innervation causes coronary veins to dilate, while parasympathetic innervation causes coronary veins to constrict.

Muscles

Coronary veins are composed of three structural layers, but only the tunica media or the middle layer of the coronary veins is smooth muscle. Comparatively, the tunica media is thinner in coronary veins than in coronary arteries.[13]

Physiologic Variants

There are numerous anatomical variations of the cardiac venous system from varied numbers of tributaries to diverse diameters and locations of the cardiac veins. Clinically, understanding unique structural variations can prove salient for a patient’s diagnosis and cardiac intervention. The most notable venous variations involve the great cardiac vein and coronary sinus.[2] The great cardiac vein usually travels along the anterior interventricular sulcus, but some patients’ great cardiac veins course intramurally, which can inhibit venous flow[5] Furthermore, other clinical findings have discovered patients with duplicate coronary sinuses, which may also affect the draining of the venous system.[14]

Surgical Considerations

As the largest coronary vein, the coronary sinus is often utilized as an anatomical landmark for orientation during cardiothoracic surgery. Although most cardiac intervention procedures occur for adult patients, infant and pediatric patients suffering from congenital heart defects also undergo cardiac operations. One congenital atrial septal defect, known as the unroofed coronary sinus, involves an anomalous and unclosed connection between the coronary sinus and the left atrium.[15] If left untreated, unroofed coronary sinus can lead to heart disease. Closure between the coronary sinus and left atrium via a stent requires careful surgical management and coordinated teamwork among physicians and medical staff to deliver the best medical care for patients and their families.

Clinical Significance

The coronary venous system encompasses significant clinical value for a wide range of cardiac interventional procedures, including cardiac catheterization, retrograde cardioplegia, reperfusion of cardiac veins, drug delivery, stem cell therapy, and lead placement among many.

For clinical treatment and procedures, the most salient anatomical feature of the cardiac veins is the coronary sinus and its venous tributaries. When patients undergo open-heart surgeries or have obstructions in their coronary arteries, the myocardium must continue to receive nourishment. To prevent ischemia of the operated heart, implementing reperfusion of the coronary sinus and its venous tributaries allows an effective reverse flow of nourishment.[16] The distribution of drugs and cardioplegic solutions via the coronary sinus also holds clinical significance. In several research reports, cardiothoracic surgeons have observed that delivery through cardiac veins can prolong contact time and enhance the efficacy of the treatment even more than the delivery through cardiac arteries can.[17][18]

Due to its optimal location and high visibility, the coronary sinus is also a popular vein for retrograde cardioplegia, temporary cessation of the heart’s activity, and is targeted for left ventricular lead placement.[19] For cardiac catheterization and pacemaker placement, the left ventricular lead advances through the coronary sinus into the posterior or lateral coronary vein to enter the left ventricular wall. This procedure allows physicians to evaluate cardiac conduction and the patient’s overall coronary health.[20] From therapeutic drug delivery to permanent pacemaker insertion, these various cardiac techniques highlight the importance of the coronary venous system and the knowledge of its unique anatomy.

Other Issues

Electrocardiography, computed tomographic (CT) angiography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are excellent noninvasive diagnostic tools to evaluate the coronary sinus and detect potential cardiac anomalies, such as congenital abnormalities and vessel obstruction.[21]