Introduction

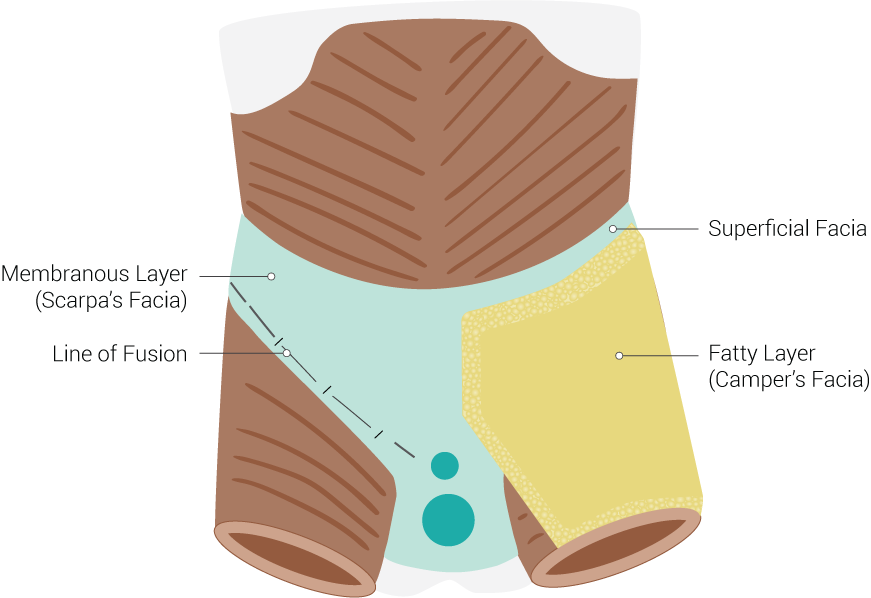

Camper's fascia is the superficial fatty layer of the anterior abdominal wall. This fascia is composed of loose areolar tissue and is found deep in the skin and superficial to Scarpa's fascia. Magnetic resonance imaging shows a 3-dimensional architecture of fibrous septae that functions to provide support to the adipose tissue.[1]

Camper's fascia spans from the xiphoid process to the seventh and 10th costal margins laterally and to the inguinal ligaments inferiorly. It continues inferiorly past the inguinal ligament as the subcutaneous fat of the thigh. Medially, the fascia extends past the pubic symphysis, combining with Scarpa's fascia to form the dartos tunic of the scrotum in males and the fatty tissue of the mons pubis and labia majora in females.

Camper's fascia is important to understand due to its function, its location in surgery, and the role it plays in healing to form a strong barrier over the abdomen.[2][3]

Structure and Function

Camper's fascia serves as a protector and an insulator to the deep, vital organs of the abdomen. The function of the fatty layer is to absorb impact and dissipate forces across a large surface area to reduce the amount of impact that is transmitted internally. The adipose tissue also acts as insulation to help maintain a constant temperature within the abdomen. Its thickness varies depending on one's body habitus.

As a part of the fascial layers of the abdomen, Camper's fascia serves a vital role by separating the skin from the muscles.[4] In the skin, there are nerve endings that contribute to touch, proprioception, and pain. Muscular nerve endings are responsible for muscle contraction and tone. If there is a break in the fascial plane, new nerve connections can form and cause undesirable outcomes.[5]

Embryology

Camper's fascia originates from the mesoderm. The mesoderm also forms bones, muscles, other connective tissues of the skin, some organs, including the heart, the urogenital system, and blood cells. Specifically, it is the dorsal mesoderm that forms sclerotomes (skeleton), myotomes (skeletal muscles and appendage buds), and dermatomes. The dermatome derivatives contribute to the connective layers of the skin that result in the formation of Camper's fascia.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior and lateral aspects of the abdomen are supplied by the superior and inferior epigastric arteries, vertically, and the lateral segmental arteries (branching from the intercostal and lumbar arteries), horizontally. These superficial abdominal vessels are found deep to the Camper's fascia and superficial to the Scarpa's fascia. These structures mark an important landmark for surgery, as to avoid damaging the vessels and lymphatics running through this area.[6]

Nerves

The iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and lower intercostal nerves supply motor control and sensory feedback to the abdominal wall. The seventh, eighth, and ninth intercostal nerves supply the supraumbilical part of the rectus abdominis and the epigastric skin. The 10th intercostal nerve supplies skin sensation at the level of the umbilicus and motor innervation extending inferiorly to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine. The 11th intercostal nerve supplies sensation below the umbilicus to the level of the inguinal ligament. Finally, the 12th intercostal nerve supplies sensation to the skin, extending inferiorly to the skin above the groin. All of the nerves mentioned above must pass through Camper's fascia to innervate the skin. Thus, edema of the skin can cause disturbances in sensation due to stretching of the nerve endings in the fascial layers of the skin.

Muscles

The muscles of the abdominal wall, externally to internally, are the external oblique muscle, internal oblique muscle, transversalis muscle, and the rectus abdominis muscle. These muscles are all found deep to both Camper's fascia and Scarpa's fascia. Both layers of fascia are important in separating the muscular layers from the integument.

Physiologic Variants

Depending on the location of the Camper's fascia, there are variations in the depth and consistency of tissue. Over the lower abdomen, it is thicker. Some areas of the tissue have more membranous intersections within the fatty fascia, which increases the appearance of dimples in the occasion of heavy edemata, such as with cellulitis.

Surgical Considerations

The abdominal fascia layers are essential considerations when it comes to surgery of the abdomen. Care is necessary to avoid important structures running within the fascial planes. Closure of the fascia is important to prevent dehiscence and the creation of possible sites of herniation and seromas. There are two main types of closures: mass closure with skin closure or individual fascial closure with skin closure. The mass closure is associated with fewer recurrences of herniations and seroma formation due to the closure of the space between the Camper's and Scarpa's fascia. Individual fascia closure runs the risk of creating a space between the layers, leading to the increased potential of a seroma and dehiscence. It is recommended to use a continuous suture with slowly absorbable sutures to decrease the incidence of herniation.[7][8]

In the realm of obstetrics, the appropriate approximation of the Camper's fascia is of particular importance during cesarean delivery. In patients with >2 cm of subcutaneous adipose tissue, the approximation of the subcutaneous tissue has shown to reduce the risk of postoperative wound disruption after cesarean delivery.[9][7] However, an approximation of the subcutaneous tissue may not reduce the risk of superficial wound disruption in vertical midline incisions in women with 3 cm or more subcutaneous fat.[10]

Clinical Significance

Camper's fascia provides strength and insulation to the abdominal wall. The strength of Camper's fascia is of particular clinical relevance when considering the risk of postoperative hernia formation. Generally, the fascia provides enough support to prevent the vertical extension of a hernia.

Given the high-fat content of Camper's fascia, there have been isolated reports of panniculitis originating within the fascia.

Severe burns have the potential to damage Camper's fascia if the skin is completely infiltrated, leading to increased fluid loss. The fat content of Camper's fascia serves to prevent water loss through the skin. Without this fatty layer, severe hypovolemia is more likely to occur.

As mentioned in the "Nerves" section, nerves can be negatively affected if the fascial plane is interrupted. In the setting of fascial plane interruption, there is a possibility that the sensory nerves of the skin may begin to communicate aberrantly with the motor nerves of the abdominal muscles, potentially leading to miscommunication, as motor signals can cause cross-talk with the skin and vice-versa. The proper alignment of the fascial planes upon surgical closure is essential to avoid this complication.

Scars may also form within the fascia following penetrating or blunt trauma. The scar tissue may adhere to the fascia to other tissues in the adjacent area, which may lead to pain in the area and are palpable as knots or deficits of tissue under the surface of the skin.