Introduction

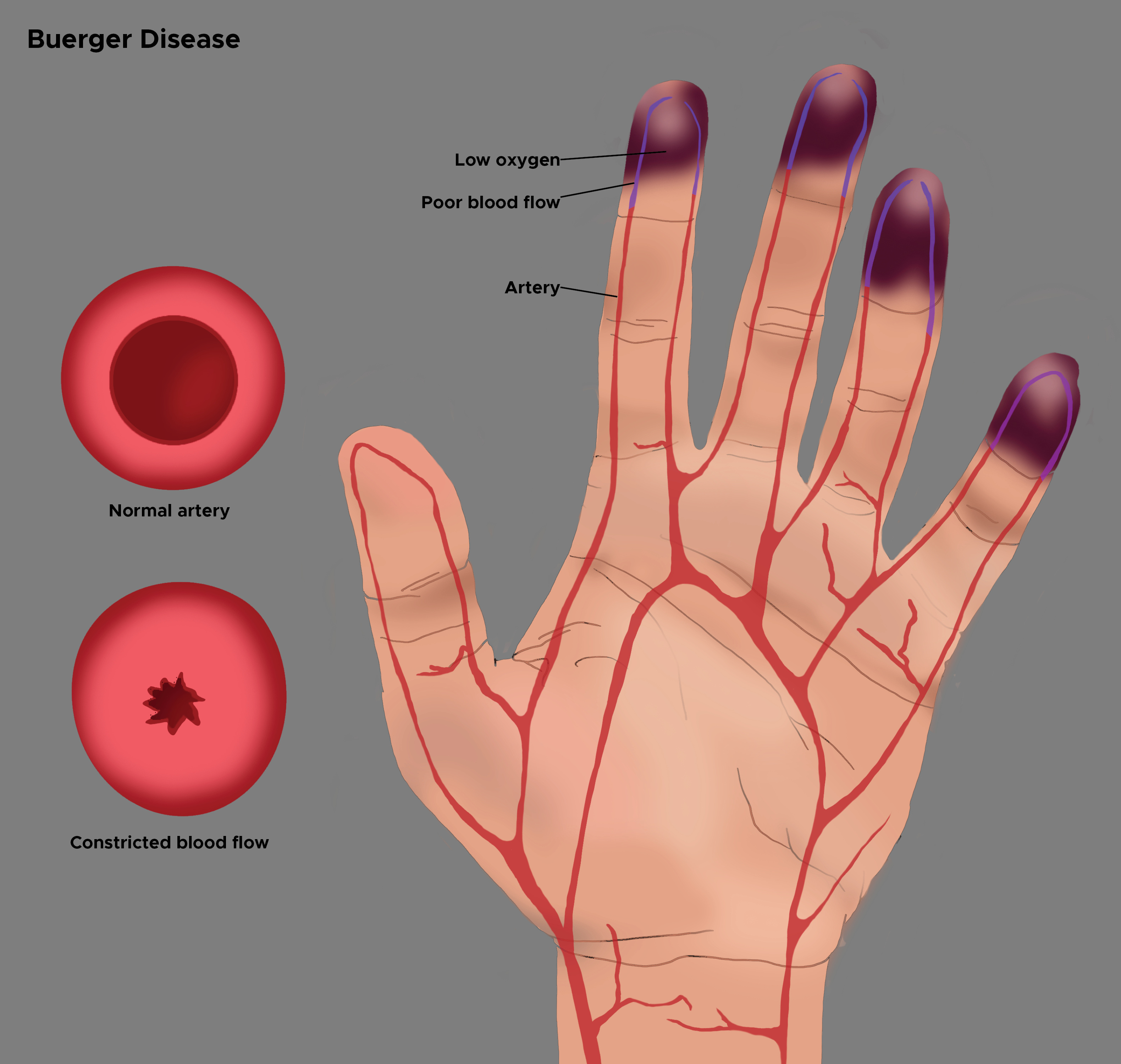

Buerger disease, also known as thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO) is a progressive, nonatherosclerotic, segmental, inflammatory disease that most often affects small and medium arteries of the upper and lower extremities. Initially described by von Winiwarter in 1879, although the eponym was given to Leo Buerger who published extensive pathologic findings from the amputated limbs of afflicted patients in 1908. The typical age range for occurrence is 20 to 50 years, and the disorder is more frequently found in men who smoke. Migratory superficial phlebitis can be present in up to 16% of patients and indicates a systemic inflammatory response.[1][2][3][4]

Patients initially present with the foot, leg, arm, or hand claudication which may be mistaken for joint or neuromuscular problems. Progression of the disease leads to calf claudication, and eventually, ischemic rest pain and ulcerations on the toes, feet, or fingers. This is also called Raynaud phenomenon.

The treatment of TAO revolves around strict smoking cessation. In patients who can abstain, disease remission is impressive, and amputation avoidance is increased. The role of surgical intervention is minimal in Buerger disease as there is often no acceptable target vessel for bypass. Furthermore, autogenous vein conduits are limited secondary to coexisting migratory thrombophlebitis.[5][6][7]

Etiology

There is no definitive etiology of Buerger disease, yet tobacco exposure is required for both disease initiation and progression. The mechanism of the disease remains a mystery, but it may involve immunologic dysfunction and tobacco hypersensitivity that is associated with enhanced cellular sensitivity to type-1 and type-3 collagen, impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation, and increased anti-endothelial cell antibody titers. A genetic link may exist as affected subjects have an increased prevalence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A9, HLA-B5, and HLA-54.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of Buerger disease has diminished over the past 5 years because of decreased smoking and adherence to more stringent diagnostic criteria. The highest incidence occurs in Israeli Jews of Ashkenazi descent and natives of Indian, Korean, and Japanese ancestry.[8] It is less frequent in subjects of northern European descent. Death from TAO is unusual, but morbidity is substantial. When affected patients continue to smoke, 43% require 1 or more amputations in 7.6 years.

United States Statistics

In 1947, in the United States, there were 104 cases per 100,000 population. Over time, the prevalence has reduced to approximately 12.6-20 cases per 100,000 population.

Age, Gender, and Race-related Distribution

Most patients with Buerger disease are aged 20-45 years. It does not occur in the pediatric or elderly population. It is more common in men with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1; however, a rise in the cases among women is being observed, which could be attributable to the growing trend of smoking in women.

Pathophysiology

Pathologically, in Buerger disease, thrombosis occurs in small to medium arteries and veins with associated dense polymorphonuclear leukocyte aggregation, microabscesses, and multinucleated giant cells. The chronic phase of the disease shows a decrease in the hypercellularity and frequent recanalization of the vessel lumen. End-stage lesions demonstrate organized thrombus and blood vessel fibrosis. Although the disease is common in Asia, North American males do not appear to have any particular predisposition, as the diagnosis is made in less than 1% of patients with severe limb ischemia.

In contrast to atherosclerosis, which involves the intima and media, Buerger disease is manifested by the infiltration of round cells in all 3 layers of the arterial wall. Patients with Buerger disease may have specific cellular immunity against arterial antigens, specific humoral anti-arterial antibodies, and elevated circulatory, immune complexes, but a precise diagnosis can be made only by tissue histology.

History and Physical

Pathologically, in Buerger disease, thrombosis occurs in small to medium arteries and veins with associated dense polymorphonuclear leukocyte aggregation, microabscesses, and multinucleated giant cells. The chronic phase of the disease shows a decrease in the hypercellularity and frequent recanalization of the vessel lumen. End-stage lesions demonstrate organized thrombus and blood vessel fibrosis. Although the disease is common in Asia, North American males do not appear to have any particular predisposition, as the diagnosis is made in less than 1% of patients with severe limb ischemia.

In contrast to atherosclerosis, which involves the intima and media, Buerger disease is manifested by the infiltration of round cells in all 3 layers of the arterial wall. Patients with Buerger disease may have specific cellular immunity against arterial antigens, specific humoral anti-arterial antibodies, and elevated circulatory, immune complexes, but a precise diagnosis can be made only by tissue histology.

Patients with Buerger disease typically present with ischemic signs and symptoms in the distribution of the distal arteries of the upper or lower extremities. Manifestations may include claudication in the arch of the foot as well as the calf. This is also called the Raynaud phenomenon or livedo reticularis that presents as pain in hands, feet, and digits at rest. TAO commonly begins in the distal extremities, but as the disease progresses, it will affect the proximal vessels. The Allen test is done to test the extent of the initial disease. Superficial thrombophlebitis complicates almost half of all cases of TAO. Due to associated neurologic involvement, paresthesias of the acral portions of the upper and lower extremities are often described.

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

No specific laboratory tests are available that confirm the diagnosis of Buerger disease. Comprehensive serology should be completed to rule out other causes for ischemic digits including thrombophilic states, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases. Some studies show that the level of anticardiolipin antibody may be a predictor of the age of onset of disease as well as a risk of amputation.

Radiographic Studies

Classic arteriographic findings include nonatherosclerotic segmental occlusions of the small- and medium-sized arteries (e.g., tibioperoneal, radioulnar, palmoplantar, and digital arteries). Arteriography may show the characteristic "pig-tailing" or "corkscrewing" of the arteries representing small collateral arteries around associated occlusions. However, corkscrew arteries are not specific for TAO. Echocardiography should be obtained to exclude a proximal source of emboli.

Histology

Acute Phase: Initial inflammatory response leads to neutrophil infiltration and granulomatous formation resulting in vessel occlusion by inflammatory thrombus with relative sparing of the vessel wall.

Subacute Phase: After the initial inflammation the thrombus organizes with continuing platelet adherence.

Chronic Phase: Inflammatory mediators are no longer present, and organized thrombus and vascular fibrosis occlude the vessel. The chronic phase may resemble atherosclerotic disease as well as other vasculitides; however, TAO may be distinguished through the maintenance of the internal elastic lamina.

Treatment / Management

Although there is no cure for Buerger disease, the cornerstone of management is smoking cessation. Even smoking 1 or 2 cigarettes per day can perpetuate the disease. Even the use of nicotine replacement therapy can keep the disease active.[9]

Symptomatic management with calcium channel blockers or other vasodilators can be implemented, especially if there is a concurrent Raynaud phenomenon. Prostaglandin analogs such as intravenous iloprost can be used to treat pain and ischemic complications. Intramuscular vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been used experimentally but the results of various studies are still inconclusive. Lumbar and/or cervical sympathectomy or spinal cord stimulators have been sporadically utilized.[10][11][12]

Intravenous (IV) iloprost appears to be helpful in relieving symptoms, improving distal-extremity trophic changes, and decreasing the amputation rate in patients suffering from Buerger disease.[13]IV iloprost therapy is most useful for slowing the progression of tissue loss and minimizing the need for amputation in patients who have critical limb ischemia in the phase when they first quit cigarette smoking.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotic analgesia can be prescribed to palliate pain secondary to ischemia, and appropriate antibiotics can be given to manage mild distal extremity ulcers.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is a widely accepted adjunctive treatment option that provides significant improvement in patients having diabetic wounds, refractory osteomyelitis, limb ischemia, or necrotizing infection of the soft tissues. Its use in Buerger disease without revascularization options still remains experimental as the available data are excessively limited.[14]

Because of the diffuse segmental involvement of Buerger disease and its propensity to affect small and medium-sized arteries, surgical revascularization is usually not advisable. The ultimate surgical treatment for the refractory disease in patients who do not quit smoking is distal limb amputation for non-resolving ulcers, gangrene, or persistent pain. Whenever possible, amputation should be avoided.

Differential Diagnosis

Following are some important options to be considered when making a diagnosis of Buerger disease:

- Antiphospholipid syndrome and pregnancy

- Imaging in polyarteritis nodosa

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

Prognosis

Death from Buerger disease is a rare phenomenon. Between 1999 and 2007, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Buerger disease was the cause of 117 deaths in the United States.

An evident dichotomy is seen in the prognosis of patients with Buerger disease, which depends on whether complete avoidance of tobacco is gained.

Complications

Potential complications of Buerger disease include the following:

- Gangrene

- Ulcerations

- Infection

- Amputation

- Rarely, occlusion of coronary, splenic, renal, or mesenteric arteries

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with Buerger disease must be advised again and again to quit all exposure to tobacco products and reassured that if they can quit tobacco use, the disease will go into remission and amputation could be avoided.

Providers should educate patients that the level of tobacco avoidance that is required to achieve resolution of the disease often requires that they vehemently curtail the exposure to secondhand smoke as well. It can be very difficult for patients who share their space with another smoker therefore it is reasonable to refer such patients and their associates to multidisciplinary smoking quitting programs.

Pearls and Other Issues

Experimental Therapies

Therapeutic angiogenesis has been evaluated for the treatment of peripheral artery disease, and this therapy may improve the ischemic manifestations of thromboangiitis obliterans. Short-term results of therapeutic angiogenesis using growth factors or autologous bone marrow have been promising, but longer-term studies are needed.

Immunoabsorption therapy was tested in a pilot study of 10 patients. The treatment was tolerated without side effects. Pain intensity decreased rapidly from a mean of 7.7/10.0 before treatment to 2.0/10.0 at the second day of five consecutive days of therapy. One month after immunoabsorption, all patients were without pain, an effect that persisted over the follow-up period of 6 months.

Bosentan, which is an endothelin receptor antagonist, was used to treat 12 patients with thromboangiitis obliterans and ischemic ulceration or rest pain. An increase in distal flow was observed in 10 out of the 12 patients on magnetic resonance, and digital subtraction arteriography and clinical improvement were observed in 12 of the 13 extremities; however, 2 extremities subsequently required amputation.

Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that suppresses platelet aggregation and is a direct arterial vasodilator. It is often used in the treatment of peripheral artery disease. In one small study, flow improvements measured in response to reactive hyperemia were significantly increased after 2 weeks of cilostazol therapy. Case reports treating patients with digital ischemia with cilostazol have reported improvements in digit pain and ulceration.

Surgical revascularization is usually not indicated due to the distal nature of the occlusive disease and because most patients do well with smoking cessation. It is accepted that surgery is rarely needed if the patient can stop smoking.

Bypass surgery may be considered in select patients with severe ischemia and suitable distal target vessels.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Buerger disease is best managed by an interprofessional team that consists of a vascular surgeon, primary care provider, nurse practitioner, pain specialist and an internist. There is no cure for the disorder and all healthcare workers should emphasize the discontinuation of smoking. Surgery is rarely done for patients with TAO and sympathectomy is unreliable. For those who stop smoking, the outcomes are good but for those who continue to smoke, the loss of digits is not uncommon.[12][6] (level V)