Continuing Education Activity

Blue nevi are melanotic dermal lesions commonly presenting as a blue nodule on the scalp, extremities, sacrococcygeal region, or buttocks. Its blue to black hue is frequently confused with other darker-pigmented lesions, including malignant melanoma. This activity outlines the evaluation, identification, and management of blue nevus and highlights the healthcare team's role in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of blue nevi.

Interpret the evaluation of blue nevi.

Differentiate the management options available for blue nevi.

Communicate interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication for blue nevi and improve outcomes.

Introduction

The term "blue nevus" describes a group of skin lesions characterized by dermal proliferation of melanocytes presenting as blue to black nodules on the head, extremities, or buttocks. (see Image. Giant Blue Nevus). In most cases, they are acquired and present as a solitary lesion but may also be congenital and appear at multiple sites. In addition to multiple less-known variants, there are 2 widely known histological subtypes: common blue nevus (dendritic blue nevus or Jadassohn-Tieche type) and cellular blue nevus.[1] Several variants of common nevi include epithelioid, sclerosing, amelanocytic, and combined.[2] See Image. Blue Nevus on Thigh.

Etiology

Blue nevi are most commonly acquired, but in rare cases, they can be congenital and associated with familial or other syndromes, such as LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxomas, and blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibromas, and ephelides). One variant, the epithelioid type, is a common manifestation in the Carney complex, a form of multiple endocrine neoplasias distinguished by pigmented skin and mucosal lesions and cardiac myxomas.[1][3]

Epidemiology

Epidemiology differs between the 2 common subtypes. Common blue nevus typically presents in young adults, while cellular blue nevus is commonly diagnosed in middle-aged individuals and shows a greater than 2 to 1 predilection for women to men. Additionally, cellular blue nevi may measure up to several centimeters as opposed to common blue nevi, which usually measures no more than 1 cm.[1]

Pathophysiology

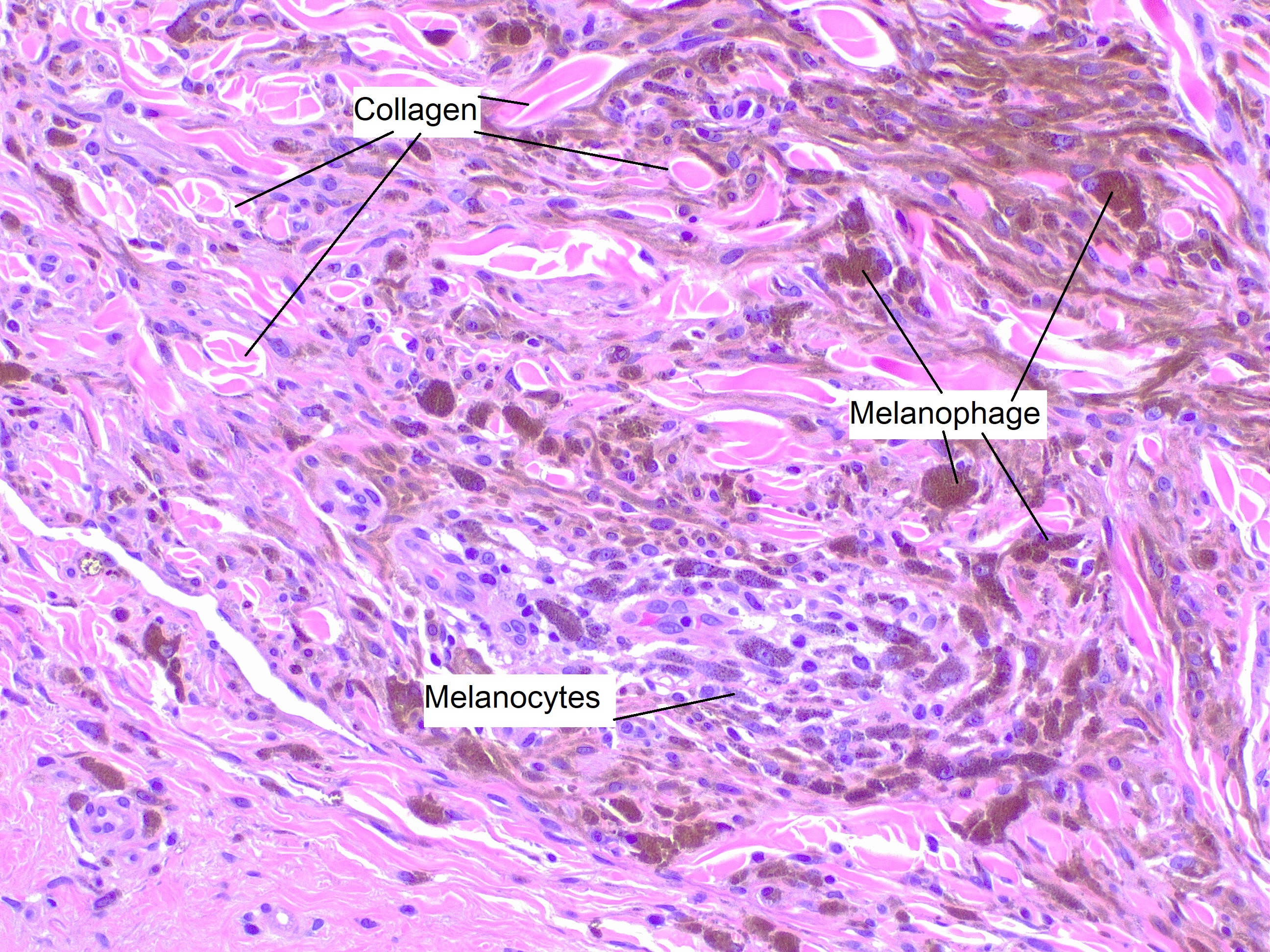

The exact etiology of blue nevus is unclear. Some postulate that components of blue nevus are remnants of migrating neural crest melanocytes during development. Others theorize that they arise from specific stem cells within the dermis.[2] The proliferation of melanocytes in the dermis and surrounding melanophages containing abundant melanin pigment create a distinctive blue hue. The characteristic blue color results from reflection, rather than absorption, of shorter wavelengths of light corresponding to the color blue by dermal melanin. This phenomenon is known as the Tyndall effect.[1][2]

Histopathology

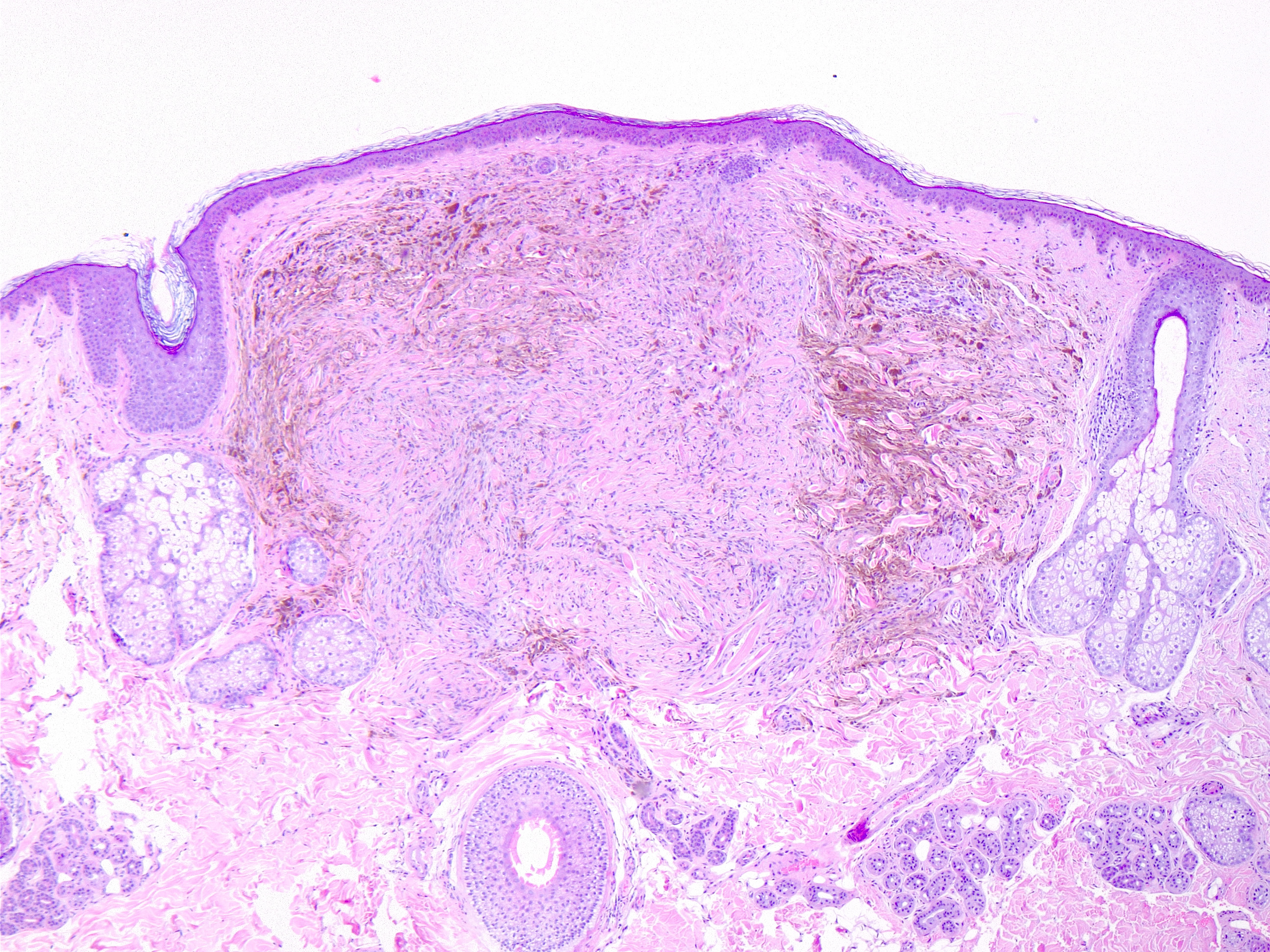

Histopathology of blue nevi varies by subtype, but general characteristics include a vertical wedge or bulbous-shaped proliferation of spindle cells, dendritic melanocytes, and melanophages into a sclerotic dermis or subcutis (see Image. Blue nevus, H/E 4x). Histologic components of various nevi types, including blue nevus, may occur together and classify as a combined blue nevus. Additional features such as atypia, increased mitotic rate, cell overcrowding, vascular invasion, and necrosis suggest malignancy and are more characteristic of blue nevus-like melanoma (BNLM).[1] Another hybrid variant, atypical cellular nevus, has histologic features of a cellular nevus with some atypia but without the overt malignant characteristics seen in BNLM.[1] HMB-45, S-100, and MART-1 stains are usually positive[2], and CD68, Melan-A, and MiTF may also be positive in the epithelioid subtype.[1]

History and Physical

Blue nevi may present as a solitary, well-demarcated, blue-to-black nodule or confluence of nodules at a single site or diffusely distributed in familial syndromes such as NAME and LAMB. Common blue nevi tend to present on the face and extremities, while cellular blue nevi occur more commonly on the buttock and sacrococcygeal regions.[1][2] Blue nevi have also presented less commonly at extracutaneous sites, including conjunctivae, oral mucosa, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, and subungual.[4][5][6][7][8]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of blue nevus is generally clinical, made grossly, or with a dermatoscope, though biopsy and pathologic evaluation are the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.[9] No other standard laboratory, radiographic, or other tests are commonly used to establish the diagnosis. Because melanoma can present clinically over a broad spectrum of morphologies, it is crucial to distinguish it from blue nevus, as the former may also commonly present as a nodule with a blue-to-black hue.[10] One standard methodology is screening for ABCDEs (asymmetry, irregular borders, color variation, diameter greater than 6 mm, evolving). Another more modern clinical tool is the “Ugly Duckling” sign based on the premise that lesions typically don’t mirror surrounding ones. More recently, there have been suggestions that the 2 be used in conjunction with 1 another to improve sensitivity.[11] When high suspicion of melanoma exists, an incisional biopsy is not a recommendation. Instead of punching or shaving, an excisional biopsy should be performed, with only a few exceptions, including larger lesions and cosmetically sensitive areas. An excisional biopsy allows more accurate and timely tumor staging and prompt referral for appropriate management in the case of malignant lesions.[12]

Treatment / Management

Given both the potential for misdiagnosis and association with blue nevus-like melanoma, blue nevi requires monitoring and a biopsy performed in cases of rapid change in morphology or size. This latter point is especially true in the case of cellular blue nevi, from which malignant blue nevus most commonly arise.[1][2][13][14] The definitive treatment of blue nevus is excision, though it is appropriate to monitor stable lesions clinically. In rare cases, blue nevus may recur at sites of prior excision. Though excision is considered curative, the appearance of recurrent blue nevus at a prior site should warrant biopsy or re-excision as it could represent emerging malignant blue nevus or other melanoma.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Blue nevi have a distinct appearance but are often misdiagnosed. One less common variant, amelanocytic blue nevus, may be mimicked by dermatofibroma or scar due to a lack of melanin pigment and the histologic presence of spindle cells, collagen, or sclerotic stroma (see Image. Blue nevus, H/E 20x). It also may be confused with amelanocytic melanoma. Another variant, desmoplastic blue nevus, histologically shows exaggerated dermal fibrosis and may be confused with desmoplastic melanoma.[1] Additionally, blue nevus-like melanoma must be distinguished from blue nevi, especially the cellular subtype, to avoid delayed diagnosis and treatment, as the 2 are frequently mistaken.[1][2]

Prognosis

The prognosis of blue nevus is good, as the lesion in its pure form is benign.[1] However, though blue nevus-like melanoma arising from blue nevus is rare, most known cases have behaved aggressively and resulted in metastasis and death.[1] A retrospective analysis showed that BNLM carries a risk of metastasis and prognosis similar to conventional melanoma when comparing lesions of equivalent depth and staging.[2][15]

Complications

There are no common significant complications associated with benign blue nevi. Malignant transformation or de novo melanoma involving cellular blue nevi carries the risk of metastasis but is rare.[1][2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Due to their benign nature, blue nevi that remain clinically stable do not require biopsy.[1] Lesions that are new or changing should have a biopsy to rule out blue nevus-like or other melanoma.[1][2][13][14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Considerable controversy exists regarding the classification and identification of blue nevi, especially concerning blue nevus-like melanoma. A more traditional term, malignant blue nevus, has been used to describe melanoma arising at the site of the blue nevus. The term is somewhat antiquated, as many have pointed out that the term implies that all cases involve a malignant transformation of an existing blue nevus, which is inaccurate. Melanoma may arise de novo with features of blue nevus, at the site of a previous blue nevus excision, or within a preexisting blue nevus.[1] Others have adopted the term blue nevus-like melanoma. However, some argue the term is also limiting, as it implies all melanomas appearing in blue nevi have histologic and epidemiological characteristics of the latter, which is not necessarily the case.[2] It is essential that healthcare providers, particularly dermatologists and pathologists, understand the distinction and communicate appropriately to minimize morbidity and mortality and maximize patient outcomes.

Additionally, because blue nevi often get treated as melanomas, and clinicians may mistake the latter for benign lesions, primary care providers should be familiar with how blue nevi present clinically and recognize red flag signs that warrant biopsy or dermatology referral. Dermatologists should be comfortable and familiar enough with the presentation of blue nevi to avoid unnecessary procedures while maintaining a healthy respect for their malignant potential and appropriate clinical acumen to biopsy them when necessary. Dermatology-specialized nursing staff can be valuable in assessing and treating these lesions, especially during excisions, subsequent follow-ups, and patient counsel. All these clinicians, specialists, and nursing staff must collaborate as an interprofessional team to guide these cases to optimal outcomes.