Introduction

Blood pressure is a cardinal vital sign that guides acute and long-term clinical decision-making. Given its importance in directing care, measuring blood pressure accurately and consistently is essential.

In general, 2 values are recorded during the measurement of blood pressure. The first, systolic pressure, represents the peak arterial pressure during systole. The second, diastolic pressure, represents the minimum arterial pressure during diastole. Finally, a third value, mean arterial pressure, can be calculated from the systolic and diastolic pressures. The formula used is as follows:

- MAP = DP + 1/3 (SP - DP) or MAP = DP + 1/3 (PP)

- PP = pulse pressure

Another method of blood pressure measurement is in use, termed automated office BP (AOBP). The AOBP measurement assesses blood pressure after the patient has rested for 5 minutes, followed by a fully automated series of 5 readings over 5 minutes, with the patient resting quietly alone. This method helps providers get a reading that corresponds more closely with ambulatory-awake blood pressure readings, alleviating the possibility of white-coat hypertension.[1]

Indications

Indications for measuring blood pressure include the following:

- To screen for hypertension

- To monitor the effectiveness of management

- To assess suitability for certain occupations or a sport

- To estimate cardiovascular risk

- Determining the risk of medical procedures

- Monitoring a patient's ongoing clinical state and deterioration [2][3]

Contraindications

The following are some relative and absolute contraindications for measuring blood pressure.

Relative contraindications for taking the blood pressure on the affected arm using a cuff are:

- Lymphedema

- Paresis or paralysis[4]

- Arterial or venous lines, such as venous catheters

Absolute contraindications for taking the blood pressure on the affected arm using a cuff are:

- Dialysis shunt

- Recent surgical wounds

- Mastectomy

Equipment

Manual Auscultation

The original method of determining blood pressure via the auscultation of Korotkoff sounds continues to be a mainstay in blood pressure measurement.[5] This method utilizes a sphygmomanometer, an inflatable cuff connected to a pressure gauge (generally a mercury column). To measure an individual’s blood pressure, the deflated cuff is placed around the arm and inflated sufficiently to occlude arterial flow. At this point, the cuff's pressure exceeds the systolic pressure, and auscultation over the brachial artery reveals no sound due to complete flow obstruction.

The cuff is then gradually deflated while continuing to auscultate over the brachial artery. When the pressure in the cuff falls to the systolic pressure level, pulsatile blood flow begins to re-establish. The resulting turbulence produces characteristic tapping sounds known as Korotkoff sounds. As the cuff deflates to the diastolic pressure level, pulsatile blood flow occurs smoothly, and Korotkoff sounds disappear. Thus, the systolic pressure is indicated by the origination of Korotkoff sounds, and their disappearance indicates the diastolic pressure.[6][7]

The Korotkoff sounds heard when measuring blood pressure are:

- Phase 1 is a faint but clear tapping sound that gradually increases in intensity

- Phase 2 is the dampening of this sound, which may be heard like blowing or swishing

- Phase 3 is when the sharper sounds return that does not have the intensity of phase 1

- Phase 4 is a well-defined muffled sound that progresses to become soft and blowing

- Phase 5 is the absence of sounds

Medical professionals should be aware of the auscultatory gap, which can result in the premature recording of diastolic pressure. In some patients, particularly those with wide pulse pressure, Korotkoff sounds can temporarily fade but reappear as the cuff deflates. Medical professionals should thus continue to auscultate over the brachial artery even when Korotkoff sounds disappear to eliminate the possibility of an auscultatory gap. Only the final disappearance of Korotkoff sounds should be used to record the diastolic pressure.[6]

Automated Devices

Automated devices can also be used to measure blood pressure. Rather than auscultating for Korotkoff sounds, these devices measure oscillations in blood flow as the cuff is deflated.

Device-specific algorithms are then used to calculate blood pressure indirectly. An advantage of automated measurements is that they require little user knowledge and are thus suitable for use by laypersons in non-medical environments.

Invasive Monitoring

The most accurate method of obtaining blood pressure measurements is using an invasive probe inserted directly into the lumen of an artery.[8] An advantage of invasive monitoring is the ability to display blood pressure variations with each heartbeat. However, given the invasive nature of this method and the associated risks, its use is limited to critical care or operative settings. As such, this review focuses on the previously mentioned blood pressure measurement methods.

Personnel

Any healthcare provider or caregiver trained to measure blood pressure can perform this examination.

Preparation

Following are some necessary preparatory steps to be taken when measuring blood pressure:

- The patient should be explained the need to take their blood pressure and the procedure for informed consent.

- It is also essential to reassure the patient and alleviate anxiety to avoid false readings.

- Ensuring the correct size of the cuff is crucial, as incorrect size may give inaccurate readings. Most guidelines advocate the use of a large cuff for all patients.

Technique or Treatment

Blood pressure is remarkably labile. Therefore, even the most insignificant activities can result in substantial changes in blood pressure readings. Accordingly, medical professionals should always properly prepare the patient and environment before cuff inflation, regardless of whether a manual or automated method is used to measure blood pressure.

First, the patient should be questioned regarding caffeine consumption, exercise, or smoking. If any of these activities have occurred within the last 30 minutes, blood pressure measurement should be postponed until this period has passed. Next, the patient should be encouraged to empty their bladder. Upon return, the patient should be seated on a chair with back support in a quiet room. Both feet should be flat on the floor with uncrossed legs, and this seated position should be maintained for at least 5 minutes.

At this time, a properly sized cuff should be placed directly over the patient’s arm. No clothing should be underneath the cuff, and sleeves should not be rolled above it. Once the cuff is in position, the patient’s arm should be supported so that the middle of the cuff is at the level of the right atrium. Blood pressure measurement can now be initiated. The patient should not speak or be spoken to while taking measurements.

There is significant variation among automated devices, and users should refer to instruction guides on initiating cuff inflation and measuring blood pressure. If a manual measurement is being performed, the bell or diaphragm of a stethoscope should be placed over the medial antecubital fossa over the approximate location of the brachial artery. The blood pressure cuff should be inflated 30 mmHg beyond the point where the radial pulse is no longer palpable. Deflation of the cuff should occur in a slow and controlled manner at a rate of 2 to 3 mmHg per second. As mentioned previously, the appearance of Korotkoff sounds signifies systolic pressure, while the cessation of these sounds indicates diastolic pressure.[9][6][10][7]

Invasive arterial blood pressure measurement is the gold standard in intensive therapy units. It can take beat-to-beat blood pressure readings, reflecting the real-time fluctuations of blood pressure.[11]

Complications

The most common source of error in blood pressure measurement is a failure to adhere to the proper technique. Multiple studies have attempted to quantify the impact of common mistakes. Smoking within 30 minutes of measurement can raise the systolic blood pressure to 20 mmHg, while a distended bladder can increase systolic and diastolic measurements by 10 to 15 mmHg. Sitting in a chair lacking back support can raise systolic blood pressure to 10 mmHg, and a similar increase is observed when both legs are crossed. Cuff placement over clothing can affect measurements by an astonishing 50 mmHg. Talking/listening during measurements can increase systolic and diastolic measurements by 10 mmHg. An improperly sized cuff can affect blood pressure in either direction; a larger cuff results in falsely low measurements, while a smaller cuff results in falsely elevated measurements. Similarly, incorrect arm positioning also results in a bidirectional error; placing the arm below the level of the right atrium results in higher values, whereas placing the arm above the right atrium generates lower values. The vast range of these errors highlights the importance of adhering to the appropriate technique when measuring blood pressure.[10]

In addition to the adjustable source of error, there are also unavoidable sources. Multiple studies have found differences between measurements obtained in clinical settings and those taken in ambulatory settings. Hypertension can be inaccurately diagnosed in patients prone to “white-coat hypertension,” a phenomenon in which the apprehension of being in the presence of a medical professional results in a transient rise in blood pressure. These patients are normotensive in ordinary settings and are hypertensive only in clinical settings. Similarly, hypertension can be inadvertently overlooked in patients who appear to be normotensive in the clinic but are hypertensive throughout other points of the day. This “masked hypertension” may be due to lifestyle changes made before medical appointments.[9]

Clinical Significance

Hypertension

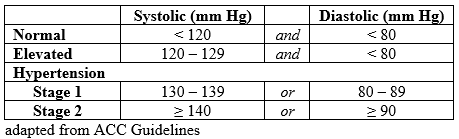

When clinically feasible, 2 or more measurements taken at different visits should be used to diagnose hypertension. The threshold at which high blood pressure is diagnosed is constantly evolving in response to new evidence. Previous guidelines had defined hypertension as beginning at a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg, but the most recent updates have lowered this level based on the benefits of early intervention.[9] Current thresholds are listed in the table (see Image. Stages of Hypertension).

Undiagnosed hypertension places patients at increased risk of developing coronary artery disease, stroke, and end-stage renal disease, among other complications. In the United States, hypertension is the second most preventable cause of death; worldwide, it is the leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years.[12][13] Thus, a timely and accurate diagnosis of hypertension is essential to initiate treatment that prevents or reduces the occurrence of these complications.

Hypotension

Hypotension is less common than hypertension and is generally due to an identifiable cause, such as dehydration, illness, or medication side effects. While there is no formal threshold for the diagnosis of hypotension, medical professionals generally use a systolic pressure of less than 90 mmHg or a diastolic pressure of less than 60 mmHg.[14][15] More commonly, the diagnosis is guided by patient symptoms, including light-headedness, dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, and weakness.

Orthostatic Hypotension

Some patients are normotensive at rest but experience symptoms of hypotension when standing. Such orthostatic hypotension is defined by a decrease in systolic blood pressure of 20 mmHg or a reduction in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg after 3 minutes of standing from a sitting or supine position.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All healthcare workers (including nurse practitioners) who measure blood pressure should know what the numbers mean. Knowing when to treat the patient and the current guidelines is important.[16][15] This measurement should be obtainable by clinicians, nurses, chiropractors, and other ancillary healthcare practitioners.