Continuing Education Activity

Pulmonary barotrauma is a potentially life-threatening complication in patients on mechanical ventilation. It is important to recognize and quickly act to prevent barotrauma for prolonged periods as this may lead to significant morbidity and mortality in patients intubated in the intensive care unit. This activity will highlight how to recognize, diagnose, prevent, and manage barotrauma in patients on mechanical ventilation.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of pulmonary barotrauma.

Review the risk factors for developing pulmonary barotrauma.

Summarize the management options for patients with pulmonary barotrauma.

Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by pulmonary barotrauma.

Introduction

Barotrauma is damage to body tissue secondary to pressure difference in enclosed cavities within the body. Barotrauma is commonly observed in scuba divers, free-divers, or even in airplane passengers during ascent and descent. The most common organs affected by barotrauma are the middle ear (otic barotrauma), sinuses (sinus barotrauma), and the lungs (pulmonary barotrauma). This article will focus on pulmonary barotrauma.[1]

Pulmonary barotrauma is a complication of mechanical ventilation and has correlations with increased morbidity and mortality.[2] The natural mechanism of breathing in humans depends on negative intrathoracic pressures. In contrast, patients on mechanical ventilation ventilate with positive pressures. Since positive pressure ventilation is not physiological, it may lead to complications such as barotrauma.[3] Pulmonary barotrauma is the presence of extra alveolar air in locations where it is not present under normal circumstance. Barotrauma is most commonly due to alveolar rupture, which leads to an accumulation of air in extra alveolar locations. Excess alveolar air could then result in complications such as pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema.[4] Mechanical ventilation modalities include invasive mechanical ventilation and non-invasive mechanical ventilation, such as bilevel positive airway pressure. The incidence of barotrauma in patients receiving non-invasive mechanical ventilation is much lower when compared to patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation. Patients at high risk of developing barotrauma from mechanical ventilation include individuals with predisposing lung pathology such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, interstitial lung disease (ILD), pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[5]

Etiology

Pulmonary barotrauma results from positive pressure mechanical ventilation. Positive pressure ventilation may lead to elevation of the trans-alveolar pressure or the difference in pressure between the alveolar pressure and the pressure in the interstitial space. Elevation in the trans-alveolar pressure may lead to alveolar rupture, which results in leakage of air into the extra-alveolar tissue.

Every patient on positive pressure ventilation is at risk of developing pulmonary barotrauma. However, certain ventilator settings, as well as specific disease processes, may increase the risk of barotrauma significantly. When managing a ventilator, physicians and other health care professionals must be aware of these risks to avoid barotrauma.

Specific disease processes, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, interstitial lung disease (ILD), pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), may predispose individuals to pulmonary barotrauma. These diseases are associated with either dynamic hyperinflation or poor lung compliance, both of which predispose patients to increased alveolar pressure and ultimately barotrauma.[6]

Patients with obstructive lung disease, COPD, and asthma are at risk of dynamic hyperinflation. These patients have a prolonged expiratory phase, and therefore have difficulty exhaling the full volume before the ventilator delivers the next breath. As a result, there is an increase in the intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), also known as auto-PEEP. The hyperinflation is progressive and worsens with each tidal volume delivered. It leads to overdistention of the alveoli and increases the risk for barotrauma. Dynamic hyperinflation can be managed by decreasing the respiratory rate, decreasing the tidal volume, prolonging the expiratory time, and in some cases by increasing the external PEEP on the ventilator.[7] The static auto-peep is easily measurable on a ventilator by performing an expiratory pause; by using this method you would obtain the total PEEP, the external PEEP subtracted from the total PEEP will equal the intrinsic PEEP or auto-PEEP. In many cases, auto-PEEP results in ventilator asynchrony, which may result in an increased risk of barotrauma. For a patient to be able to trigger a breath on the ventilator and for the flow to begin, the inspiratory muscles must overcome the recoil pressure. When intrinsic PEEP is present, it imposes an additional force that the inspiratory muscles have to overcome to trigger a breath. In many instances, auto-PEEP may lead to ventilator asynchrony, increased alveoli distention, and ultimately barotrauma.[8]

Elevated plateau pressure is perhaps one of the most critical measurements of which to be aware. Plateau pressure is the pressure applied to the alveoli and other small airways during ventilation. Elevated plateau pressures, particularly pressures higher than 35 cmH2O, have been associated with an elevated risk for barotrauma.[9] Plateau pressures are easily measurable on a ventilator by performing an inspiratory hold. Based on current data, as well as the increased mortality associated with barotrauma, the ARDSnet protocol suggests keeping plateau pressures below 30 cmH2O in patients on mechanical ventilation for ARDS management.[10]

Peak pressure is the plateau pressure in addition to the pressure needed to overcome flow resistance and the elastic recoil of the lungs and chest wall. The risk for barotrauma increases whenever the peak pressures and plateau pressures become elevated to the same degree.[11]

Elevated positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may theoretically lead to overdistention of healthy alveoli in regions not affected by disease and ultimately barotrauma. However, clinical data has not associated increased PEEP with increased risk of barotrauma when used in conjunction with lung protective strategies, such as low tidal volume and target plateau pressure under 30 cmH2O. If higher PEEP is necessary for oxygenation, it should be titrated up slowly with close monitoring of the peak inspiratory and plateau pressures.[12]

Epidemiology

The incidence of pulmonary barotrauma greatly depends on the underlying indication for mechanical ventilation. Several trials and meta-analysis have estimated the prevalence between 0% and 50%. More recent data after the implementation of lung-protective ventilation strategies appear to be closer to an incidence of 10% averaged between different populations.[12]

A prospective cohort study published in 2004 looked at 5183 patients throughout 361 ICUs. The incidence of barotrauma was 2.9% in general. Prevalence varied depending on the indication for mechanical ventilation. The incidence was found to be 2.9% in patients with COPD, 6.3% in patients with asthma, 10% in patients with ILD, 6.5% in patients with ARDS, and 4.2% in patients with pneumonia.[6]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology for lung injury and barotrauma due to mechanical ventilation remains unclear; however, evidence suggests that overdistention and increased pressures in the alveoli units lead to inflammatory changes and possibly rupture and leakage of air into the extra alveolar tissue.

Researchers have described several mechanisms in the literature for the rupture of alveoli. Most of the mechanisms have their basis in overdistention and increased pressures in the alveoli. Historically, large tidal volumes were the approach in patients requiring mechanical ventilation to minimize atelectasis and improve oxygenation and ventilation. Such ventilatory settings usually lead to high inspiratory pressures and overdistention of the alveolar unit. Overdistention is more pronounced in patients with ARDS and other non-uniform lung diseases. In non-uniform lung disease, not every alveoli unit is affected equally; normal alveoli receive a greater percentage of the tidal volume, which leads to preferential ventilation and ultimately overdistention to accommodate the larger tidal volume.[13]

Some animal studies have looked at the association between alveolar overdistention and lung injury. Tsuno et al. looked at histopathologic changes in the lungs of baby pigs. The settings on the ventilator produced a peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) of 40 cmH2O for up to 32 hours as well as the tidal volume of 15 mL/kg. Pathological findings on the subject's studies included interstitial lymphocyte proliferation, alveolar hemorrhage, and hyaline membrane formation; all of which are similar to the histopathology observed in patients with ARDS.[14] Other studies in human subjects have also demonstrated an association between high volume ventilation and increased levels of TNF-alpha and MIP-2; both are inflammatory cytokines researchers believe are implicated in the multi-organ dysfunction associated with ARDS.[15]

History and Physical

The history and physical exam in patients with barotrauma secondary to mechanical ventilation are usually limited since those patients are sick and under sedation while on mechanical ventilation. In cases of clinically significant pneumothorax, patients will present with acute changes in vital signs, including tachypnea, hypoxia, and tachycardia. Patients may also present with obstructive shock if a tension pneumothorax occurs. Physical examination may be significant for absent breath sounds if a pneumothorax exists. Subcutaneous emphysema may also present in some cases. In some, less severe cases, no systemic or hemodynamic changes may be present.[1]

The patient's past medical history is also essential when it comes to the diagnosis and management of pulmonary barotrauma. As mentioned previously, patients with a known history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, interstitial lung disease (ILD), pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, or ARDS, are at increased risk of developing pulmonary barotrauma. Underlying pulmonary pathology will also be important to be aware of when it comes to selecting the ventilator mode as well as the settings as we will discuss later.

Evaluation

Ventilator data may be useful in the evaluation of pulmonary barotrauma. Ventilator asynchrony, acute elevation of the plateau and peak pressures above 30 cmH2O, or sudden decrease of delivered tidal volume may suggest respiratory distress secondary to pneumothorax or other complications from barotrauma. Ventilator data can give a clue to physicians regarding which patients are at higher risk for barotrauma.

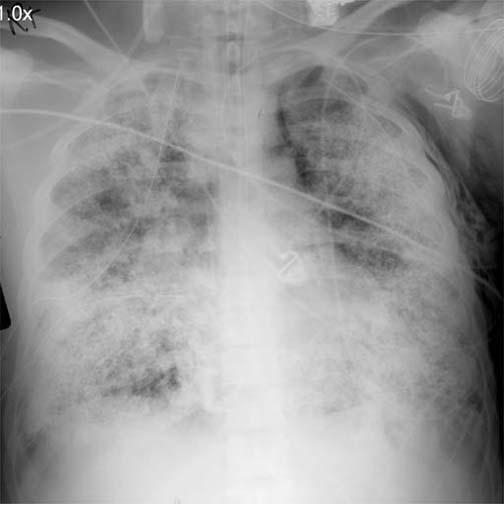

Once pulmonary barotrauma secondary to the mechanical ventilator is suspected, action must take place immediately. Pneumothorax is an acute complication from pulmonary barotrauma, which is an emergency. The physical exam will be remarkable for absent breath sounds, and in most cases, patients who can communicate will complain of shortness of breath and chest pain. Vital signs usually demonstrate hypoxia as well as hypotension secondary to obstructive shock in the case of a tension pneumothorax. In patients who develop a tension pneumothorax, action is necessary before obtaining a chest radiograph. Tension pneumothorax requires urgent needle decompression to evacuate the pneumothorax, followed by thoracotomy tube placement. In patients presenting with a less acute complication, such as a simple pneumothorax with stable vital signs, pneumomediastinum, or subcutaneous emphysema, the clinician should obtain a chest radiograph immediately. The chest radiograph is able to identify the presence of pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, subcutaneous emphysema, and other less common manifestations of pulmonary barotrauma, such as pneumatoceles, sub-pleural air collections, and pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE). If a chest x-ray is obtained but inadequate for evaluation, a CT of the chest can be done. It is important to remember that barotrauma is a clinical diagnosis and should always be high in the differential diagnosis for patients on invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation presenting with acute decompensation.[1]

Treatment / Management

There is no single strategy to prevent pulmonary barotrauma on patients on mechanical ventilation. The most efficient mechanism that has been described to prevent the risk of developing barotrauma on mechanical ventilation involves maintaining the plateau and peak inspiratory pressures low. The goal plateau pressure should be below 35 cmH2O, and ideally below 30 cmH2O, on most patients on mechanical ventilation as recommended by the ARDS Network group. Various techniques may be employed to aid in maintaining the plateau pressure at goal. Various ventilator modes are available. The two modes most commonly used in intensive care units are volume assist control (volume AC), a volume cycled mode, and pressure assist control (pressure AC), a pressure cycled mode. Lung protective ventilator strategies should be used in every ARDS and most other patients, regardless of the mode of mechanical ventilation. Lung protective ventilator strategies derive for the most part from a study published in the year 2000 by the ARDS Network group. The study involved ARDS patients and compared outcomes in ARDS patients using higher tidal volume ventilation (about 12 mL/kg of IBW) and patients using lower tidal volume ventilation (about 6 mL/kg OF IBW). Although tidal volume was the variable in this study, the goal with the low volume ventilation group was to keep the plateau pressure below 30 cmH2O. The low tidal volume ventilatory strategy correlated with a lower mortality rate (31% vs. 40%).[16] The incidence of barotrauma in this study was not lower when using lung-protective ventilator strategies; however, other studies have demonstrated a higher incidence of barotrauma when the plateau pressure rises above 35 cmH2O.[3] Low tidal volume ventilation is especially important in patients at higher risk for barotrauma, such as patients with ARDS, COPD, asthma, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP), and chronic interstitial lung disease (ILD).[6]

The driving pressure is another concept with which physicians managing patients at risk of barotrauma must be familiar. The driving pressure is measurable in patients not making an inspiratory effort; one can obtain the calculated pressure by subtracting the PEEP from the plateau pressure. Driving pressure became a hot topic of discussion after the ARDS trial proposed that high plateau pressures increase mortality in patients with ARDS but that high PEEP pressure is associated with improved outcomes. Amato et al., in 2015, proposed that the driving pressure was a better ventilation variable to stratify risk. In the trial, published in the NEJM in 2015, they concluded that an increment of 1 standard deviation in driving pressure was associated with increased mortality even in patients receiving protective plateau pressure and tidal volumes. Individual changes in tidal volume and PEEP were only associated with improved survival if these changes led to a reduction in driving pressure.[17] Based on the data available, clinicians should maintain the optimal driving pressure between 13 and 15 cm H2O.[17]

As mentioned previously, patients with obstructive lung disease are at risk of dynamic hyperinflation due to a prolonged expiratory phase, and difficulty exhaling the full volume before the ventilator delivers the next breath. Physicians must be aware of intrinsic PEEP or auto-PEEP, particularly in patients at high risk, such as those with obstructive lung disease. An expiratory pause maneuver on the ventilator will provide the static intrinsic pressure. If intrinsic PEEP is present, then the physician may increase the external PEEP to help with ventilator synchronization by allowing the patient to trigger the ventilator and initiate a breath more effectively. The goal is to increase the external PEEP by 75 to 85% of the intrinsic PEEP [8]. Other methods that the physician may employ to decrease the intrinsic PEEP include decreasing the respiratory rate, decreasing the tidal volume, and prolonging the expiratory time.[7]

High positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) may theoretically lead to overdistention of healthy alveoli in regions not affected by disease and ultimately lead to barotrauma. Many conditions, such as moderate to severe ARDS, require the use of high PEEP pressures to improved oxygenation by recruiting as many alveoli units as possible. When used in conjunction with lung protective strategies, as described above, the risk of barotrauma due to high PEEP is minimal.[12] Several methods exist to aid physicians in determining the adequate level of PEEP to treat individual patients based on lung compliance. A system pressure-volume curve may be used to determine the lower inflection point and the higher inflection point. The lower inflection point in the curve determines the minimal level of PEEP required to start alveolar recruitment. The upper inflection point in the curve determines the pressure level at which the risk of barotrauma and lung injury occurs.[18]

The stress index is another method that may be used by physicians to determine the adequate amount of PEEP for individual patients. For the stress index to be an accurate measurement, the patient must be well sedated, and the flow must be constant. The physician may look at the pressure waveform on the ventilator to determine the stress index. A pressure wave that is concave down indicates a stress index less than 1. A stress index of less than 1 indicates that the patient may benefit from increased PEEP to help with alveoli recruitment. A pressure wave that is concave up indicates a stress index higher than 1. A stress index higher than one should alert the physician that the patient's alveoli unit is at risk of distention and barotrauma. A straight diagonal line in the pressure wave is ideal because it correlates with a stress index between 0.9 and 1.1, which is the ideal range for proper alveoli recruitment with a low risk of distention and rupture.[19]

Different ventilator modes also exist, which may be better tolerated by some patients and decrease the risk of barotrauma. There is no evidence to suggest that one ventilator mode is better than the other. However, in patients who are difficult to manage, physicians may try different modes to synchronize the patient with the ventilator better.

Volume AC mode is a volume cycled mode. It will deliver a set volume on every ventilator assisted breath, which will lead to significant variations in peak inspiratory pressures as well as plateau pressures depending on the compliance of the lung parenchyma. The peak inspiratory and plateau pressures may be kept at goal using this mode of ventilation by using low tidal volume ventilation (between 6 to 8 mL/kg based on the ideal body weight). The respiratory rate and inspiratory time may be adjusted as well to prevent intrinsic PEEP. In some cases, sedation, and even neuromuscular blocking agents may be to be used to improve ventilator synchrony and maintain inspiratory peak and plateau pressures at goal.[1]

Pressure AC mode is a pressure cycled mode. It allows medical personnel to set an inspiratory pressure level as well as the applied PEEP. The advantage of using a pressure cycled mode is that the peak inspiratory pressure will remain constant and will be equal to the inspiratory pressure in addition to the PEEP. The plateau pressure will also be lower or equal to the peak inspiratory pressure; therefore, this mode of ventilation correlates with a lower rate of barotrauma. The disadvantage, however, is that the tidal volume delivered will vary depending on lung compliance. Patients with poor lung compliance may not receive an adequate tidal volume using this ventilator mode.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Bacterial/viral pneumonia

- Aspiration pneumonitis

- Shock (distributive, cardiogenic, hemorrhagic)

- Flail chest, chest trauma

- Secondary pneumothorax

- Pulmonary emboli

- Asthma exacerbation

- COPD exacerbation

- Acute coronary syndrome

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

The management of complications due to barotrauma depends on the specific complication. Pneumothorax, or tension pneumothorax, is a medical emergency. A tension pneumothorax must be treated immediately with needle decompression. The diagnosis of tension pneumothorax is made clinically and must be acted upon quickly without waiting for chest radiography. Signs and symptoms of tension pneumothorax include the absence of breath sounds, hemodynamic instability, as well as symptoms of chest pain and shortness of breath. The clinician must perform an urgent needle decompression followed by the placement of a thoracotomy tube.[20]

The management of most non-tension pneumothorax in patients on mechanical ventilation involves the placement of a thoracostomy tube to evacuate the air due to the high incidence of progression to tension pneumothorax while on mechanical ventilation.[20] Once the thoracotomy tube is in place, additional changes in the ventilator may be made to help with the resolution of the pneumothorax. Tidal volume may be decreased to decrease the plateau and peak inspiratory pressures. FiO2 in the ventilator may be increased temporarily to help decrease the partial pressure of nitrogen and aid with the absorption of air from the pleural cavity and hasten lung re-expansion.[21] PEEP should also be lowered to decrease overdistention of the alveoli units, and patients should be well sedated to prevent ventilator asynchrony and further trauma.

Other complications, such as subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, and pneumoperitoneum, are usually self-resolving and management is conservative. Conservative management involves reducing the plateau pressures below 30 cmH2O as well as continuous monitoring. Other strategies to minimize complications include reducing the PEEP on the ventilator, using sedation and neuromuscular blockade in patients who are difficult to synchronize with the ventilator, and decreasing the ventilatory pressures. Ultimately, the best way to prevent barotrauma and complications is liberating the patient from mechanical ventilation.[1]

Tension pneumomediastinum is an exception. In tension pneumomediastinum, the pressure in the mediastinum increases significantly and ultimately may lead to physiological effects similar to pericardial tamponade. It may cause compression of the great vessels and compromise the right heart filling leading to shock and eventually, cardiac arrest. Chest radiography will show a heart silhouette resembling a sphere. The initial management involves ventilator changes to decrease the airway pressures and increase the FiO2 in the ventilator to 100%. Ultimately surgical mediastinal decompression is required.[22]

Subcutaneous emphysema rarely may lead to compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome should be suspected in patients with hemodynamic instability and elevated bladder pressures. Management involves decreasing the airway pressures, but ultimately, surgical evaluation is warranted. Surgical decompression must be performed in all patients with hemodynamic instability as this condition is associated with a high mortality rate.[23]

Patients presenting with pneumoperitoneum may also progress to compartment syndrome. An immediate surgical evaluation must take place due to the high mortality associated with this condition. Pneumoperitoneum due to barotrauma is rare, and other causes for pneumoperitoneum should be ruled out, such as ruptured viscus and abdominal trauma.[24]

Hypercapnia is among the most common side effects that present when managing a patient with lung-protective ventilatory strategies. The lower tidal volume may lead to decreased minute ventilation, and in some cases, hypercapnia. Guidelines for ARDS recommend allowing for permissive hypercapnia up to a pH of 7.2. If the pH drops below 7.2, the initiation of a bicarbonate infusion should be a therapeutic consideration to correct the pH to 7.2.[25]

Prognosis

Pulmonary barotrauma while on mechanical ventilation has correlations with increased morbidity and mortality. A prospective cohort study performed in 361 intensive care units in 20 countries looked at the outcome of 5183 patients mechanically ventilated for more than 12 hours. Barotrauma was present in 2.9% of the patients. There was an increase in mortality in patients who developed barotrauma, 51 versus 39 percent.[6]

Complications

Patients who develop barotrauma secondary to mechanical ventilation also end up staying in the ICU and on mechanical ventilation for a more extended period. Prolonged time on mechanical ventilation may result in further complications secondary to barotrauma as well as others, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, delirium, intensive care acquired weakness, and nosocomial infections.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients who are cognitive before initiating mechanical ventilation should be made aware of the possible complications associated with mechanical ventilation, including barotrauma. Physicians should inform patients and family members of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with barotrauma; especially in patients with a known history of COPD, asthma, or ILD. Providers should discuss goals of care with every patient and their family members.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pulmonary barotrauma secondary to mechanical ventilation is a condition that commonly presents in the ICU. It carries high morbidity and mortality. The ICU nurses caring for patients on ventilators must be fully aware of barotrauma and how to respond. The condition can result in a life-threatening tension pneumothorax and lead to death within minutes. Nurses need to assess the patient's ventilatory parameters, frequently palpate the chest for crepitus, and check the chest X-ray. A chest tube kit should be available if patient management uses a high PEEP. The nurses need to have rapid and open communication access to the interprofessional team.

Patients with barotrauma remain on mechanical ventilation and in the ICU for an extended period. It is difficult to diagnose pulmonary barotrauma since most patients are unable to communicate. Hemodynamic changes and evidence of respiratory distress usually occur after major complications from barotrauma have already happened, such as a pneumothorax. Due to the difficulty in diagnosis, a high degree of suspicion is necessary. It is important for physicians to obtain a thorough medical history, monitor the ventilatory pressures, and carefully look at chest radiographs to identify patients at risks for barotrauma before significant complications occur. Physicians and nurses should have rounds in each patient in the ICU, and the ventilatory parameters should be discussed. No one except for the critical care physician or respiratory therapist should make ventilator changes. Each ventilator change must be recorded in the logbook, and all staff notified.

Only through open communication between clinicians and nursing staff can the morbidity of barotrauma be lowered. [Level V]