Introduction

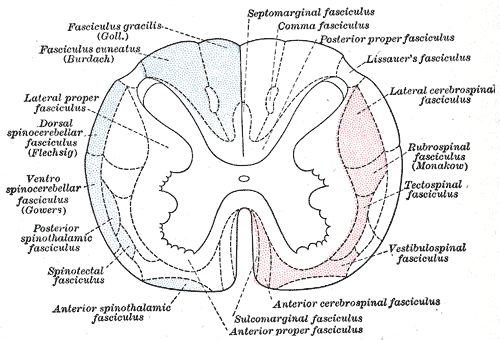

The spinal cord relies on 3 main arteries for vascular supply. The anterior spinal artery supplies the anterior two-thirds, and the 2 posterolateral spinal arteries supply the posterior third of the spinal cord.

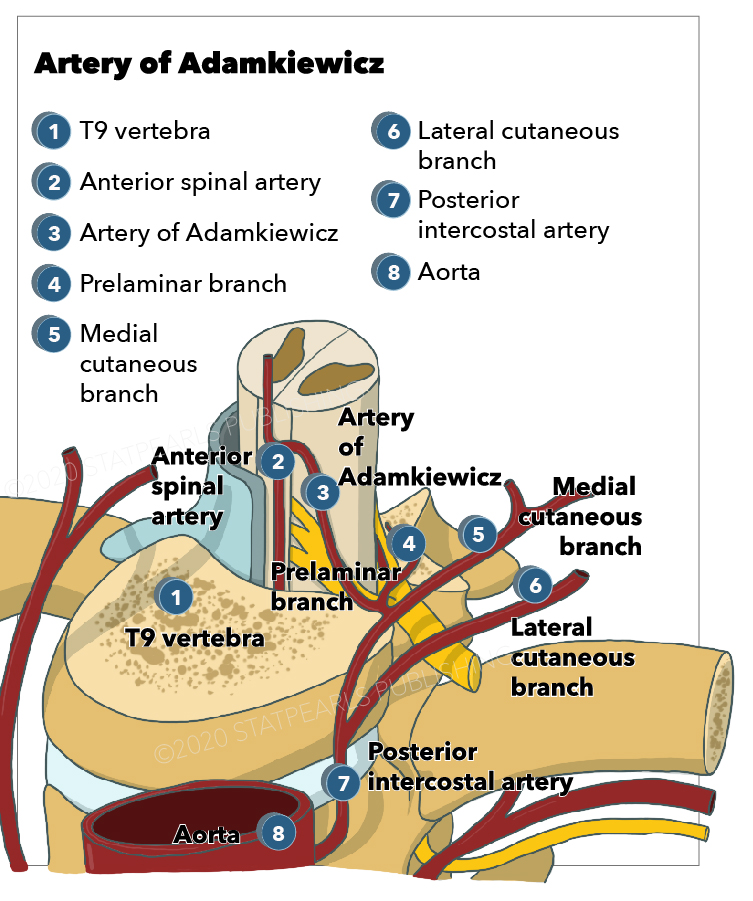

The anterior spinal artery originates from the 2 vertebral arteries at the level of the foramen magnum. It is supplied by anterior segmental medullary vessels from the aorta, the biggest of which is the artery of Adamkiewicz also referred to as the arteria radicularis magna or the great anterior radiculomedullary artery.

The anatomic course of the artery of Adamkiewicz can be traced starting from the descending aorta. Here, approximately 8 to 10 segmental (either intercostal or lumbar) arteries branch off and split into anterior and posterior branches. The posterior branch then divides into 3: the radiculomedullary artery, the muscular branch, and the dorsal somatic branch. The radiculomedullary artery then splits into the main anterior and smaller posterior radiculomedullary arteries, and the largest anterior radiculomedullary artery is named the artery of Adamkiewicz. The artery of Adamkiewicz then passes through the intervertebral foramen and enters the spinal canal adjacent to the exiting spinal nerve (usually ventral or slightly rostrolateral to the dorsal root ganglion/ventral ramus. It then travels with the ventral root to the ventral (anterior) surface of the spinal cord, ascends, makes a classic “hairpin” arch, then directs toward and joins the anterior spinal artery. [1][2][3][4]

The artery of Adamkiewicz typically arises from the left side of the aorta between T8 and L2 (usually T9 to T12, although the artery of Adamkiewicz is found above T8 in about 15% of people), and has been documented as having a diameter anywhere from 0.6 to 1.8 mm. Variants include the artery of Adamkiewicz arising from the right side of the aorta or level outside of T8 through L2, differences in the angle of how the artery of Adamkiewicz joins the anterior spinal artery, and the presence of more than one artery of Adamkiewicz. Of note, collateral circulation is possible if the artery of Adamkiewicz has progressive occlusion; collaterals usually arise from the muscular branch or other intercostal or lumbar arteries.[3][5]