Continuing Education Activity

Anthrax is an infectious disease caused by an encapsulated, spore-forming, gram-variable bacteria called Bacillus anthracis. This commonly presents with nonspecific prodromal symptoms such as fever, nausea, vomiting, and sweats which progress to dyspnea and ultimately respiratory failure and hemodynamic collapse. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of anthrax and explains the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of anthrax.

- Describe the pathophysiology of inhalational, cutaneous, gastrointestinal and injection anthrax.

- Summarize the use of vaccines in the management of anthrax.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team members to be vigilant in evaluating the possibility of bioterrorism in multiple patients presenting with the symptoms of anthrax.

Introduction

The bacteria Bacillus anthracis causes anthrax. The bacteria is a small aerobic or facultatively-anaerobic, gram-positive or gram-variable, encapsulated, spore-forming rod. The organism produces toxins which are important for clinical virulence. It grows well on blood agar resulting in large, irregular-shaped colonies. The origin of the name comes from the Greek word "anthrakis," meaning black, in reference to the necrotic lesion seen in cutaneous anthrax.[1][2][3]

Although B. anthracis is generally an environmentally-stable and ubiquitous organism in nature, it has also been recognized as a potential pathogen that could be used as a biologic weapon.

Anthrax can affect the skin or internal organs. When inhaled, anthrax is usually fatal. Symptoms usually appear several days after the infection and this makes it difficult to track the organism.

Etiology

Bacillus anthracis is environmentally stable in spore form and may contaminate soil worldwide, resulting in infections of herbivores while grazing. Spores can remain dormant and viable in the environment for decades. Animal cases of anthrax tend to occur in summer and fall seasons and are most frequent in grazing mammals including domestic sheep, goat, and cattle and wild deer and antelope. Human transmission occurs via contact with infected animals through butchering and working with hides or ingestion of raw or undercooked meat. Skin contact results in cutaneous anthrax while inhalation or ingestion of the spores leads to inhalational or gastrointestinal (GI) anthrax.[4]

Anthrax is acquired from animals; there are no reports of direct human to human transmission.

Epidemiology

Anthrax occurs worldwide, and the world health organization (WHO) estimates the annual global incidence of between 2000 and 20,000 cases. It is rare in the United States, although in the year 2000, an outbreak of anthrax occurred in the ranches of North Dakota. Skin contact results in cutaneous anthrax while inhalation or ingestion of the spores leads to inhalational, pharyngeal, or GI anthrax.[5]

Anthrax is categorized as a category A priority pathogen by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because it is potentially capable of being disseminated as a bioweapon.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of anthrax follows the route of infection with three primary forms in humans: cutaneous, GI, and inhalational.

Inhalational anthrax leads to accumulation of B. anthracis spores within the lung alveoli. The spores are engulfed by immune cells (macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells) and transported to regional lymph nodes where the bacteria germinate, multiply, and begin toxin production. This results in systemic clinical illness, and pathologically to toxin-induced cell damage and cell death. As the disease progresses, bloodstream infection occurs leading to septic shock. Patients can present suddenly and may deteriorate rapidly.

Cutaneous anthrax results from inoculation of B. anthracis spores through the abraded skin into subcutaneous tissues. The bacteria subsequently germinate and multiply locally and begin toxin production. This leads to the characteristic edema and cutaneous ulceration.

GI anthrax occurs due to ingestion of contaminated meat, with spores introduced into the gastrointestinal tract, causing bacterial replication, mucosal ulcerations, and bleeding.

Recently, injection anthrax has been described in northern European injection drug users, resulting in symptoms similar to cutaneous anthrax but with a deeper infection which may include myositis.[6]

The damage to tissues is caused by the anthrax toxins, of which the edema toxin is most lethal.

Humans are relatively resistant to cutaneous anthrax but any break in the skin can allow the organism to enter the skin. Once inside the circulation, the organism spreads rapidly and affects the lungs, kidney, and spleen. The organism can also enter the brain and cause meningitis which is universally fatal.

Histopathology

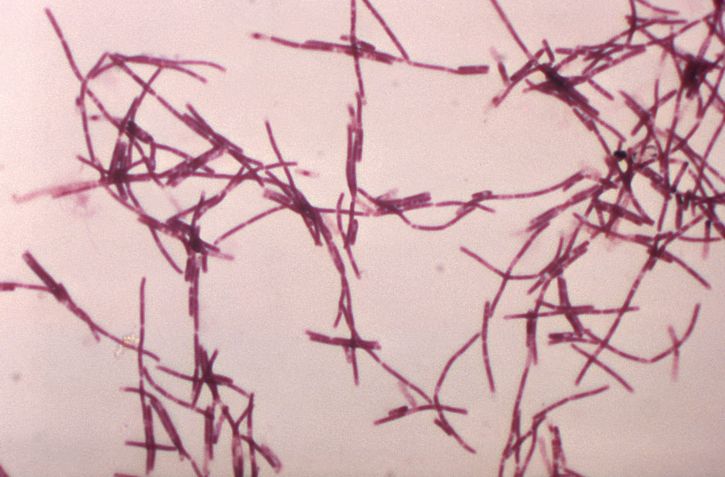

One classic feature of anthrax is the presence of the bacteria in the capillaries at the infection site. Other features include hemorrhage, necrosis, and submucosal thrombosis.The organism does have a capusle that can be visualized using indian ink stain. The classic appearance of the colonies is comma-shaped protrusions. Anthrax, unlike other rods, is not motile and lacks hemolysis on blood agar.

History and Physical

Inhalational anthrax presents following an incubation period of approximately 1 to 6 days post-exposure, with a non-specific prodromal phase including fever, sweats, nausea, vomiting, malaise, chest pain and nonproductive cough. The second stage of illness occurs as bacterial replication in mediastinal lymph nodes results in hemorrhagic lymphadenitis and mediastinitis, and progression to bacteremia. Fever, dyspnea, and stridor from increasing lymphadenopathy impacting the airways, and ultimately respiratory failure and hemodynamic collapse occur. Meningitis also occurs in up to 50% of inhalational cases, with a headache, confusion, and progression to coma. Chest x-rays classically demonstrate a widened mediastinum (the result of significant lymphadenopathy) without pulmonary infiltrates, though pleural effusions and/or pulmonary infiltrates both of which may be hemorrhagic can also be seen. The time from onset of symptoms to death ranges from 1 to 10 days.

GI anthrax results from ingestion of contaminated, undercooked meat or ingestion of spores inhaled into the nasopharynx and can include oropharyngeal and/or intestinal symptoms. Patient with oropharyngeal anthrax develops ulcers of the posterior oropharynx and associated dysphagia, cervical swelling, and regional lymphadenopathy. Patients with intestinal anthrax develop fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. They can progress to an acute abdomen-like presentation with bloody diarrhea, hematemesis, and massive ascites. Intestinal involvement more frequently involves the terminal ileum and cecum. Untreated patients will progress to septicemia. Mortality ranges from 25% to 60%.

Cutaneous anthrax presents 1 to 10 days post-inoculation with a pruritic papular lesion that progresses over several days into a painless ulcer. The lesion may have associated satellite vesicles and will progress into a necrotic and blackened center with surrounding non-pitting edema. The painlessness of the lesion is characteristic of cutaneous anthrax and a distinguishing feature from other diagnoses. As the lesion heals, the eschar will dry, and slough off after 1 to 2 weeks. Without appropriate treatment, the mortality rate can approach 20%.

Injection drug anthrax presents as a grouping of small vesicles or papules at the injection site, with progression to painless ulcerative lesion similar to cutaneous anthrax. Injection anthrax may make it more difficult to recognize and may progress more rapidly to systemic illness than cutaneous anthrax.

Evaluation

The CDC has developed detailed recommendations for patient evaluation by suspected anthrax exposure and clinical syndrome. Depending on the clinical features, relevant specimens include PCR, gram stain, and cultures, from blood, pleural fluid, site of ulceration, cerebrospinal fluid, and stool. Patients may also need routine diagnostic evaluations such as complete blood count (CBC) and chest x-ray. Testing for relevant pathogens on the differential diagnosis may need to be incorporated into the evaluation as well.[7][8]

The laboratory personnel must be warned that the tissue may contain anthrax so that they take appropriate precautions. Cutaneous anthrax is diagnosed with a methylene blue stain which reveals a gram-positive rod that is not motile.

Chest x-ray in patients with inhalational anthrax may reveal enlarged mediastinum. The CT scan may reveal enlarged hilar lymph nodes, mediastinal hemorrhage, and pleural effusions.

Treatment / Management

All cases of inhalation anthrax should be considered a bioterror event and appropriate decontamination steps should be in place. Healthcare workers should wear masks and gloves and splask protection devices.

Contaminated individuals should immediately wash hands with detergent and water. Place clothing in a plastic bag for evaluation.

Anthrax is a reportable infection and the local authorities and the CDC must be notified immediately.

The CDC has concise treatment recommendations based upon anthrax disease manifestations, including multiple alternative agents that may be considered in select patients.[7][9][8]

In brief, treatment for inhalational anthrax requires a multidrug regimen with one bactericidal agent + 1 protein-synthesis inhibitor. Intravenous ciprofloxacin + clindamycin or linezolid are the preferred agents. In patients with meningitis, a 3-drug regimen comprised of 2 bactericidal agents from different drug classes (fluoroquinolone + beta-lactam) + 1 protein-synthesis inhibitor are recommended. For cutaneous anthrax, oral ciprofloxacin or doxycycline are effective, except in cases with extensive edema or head and neck involvement, when a multidrug intravenous regimen is recommended.

An antitoxin product may be recommended as a treatment adjunct together with a multidrug antimicrobial regimen, and there are multiple products that have been developed including both monoclonal and polyclonal antitoxins.

Anthrax immune globulin should also be considered with CDC consultation as adjunctive therapy for systemic anthrax treatment.

Anthrax vaccines for humans and animals are available. Animal vaccination has greatly reduced, but not eliminated animal cases. Human vaccination is not recommended for the general US population but is recommended for high-risk professions having occupational contact with animal hides and fur including some veterinarians, certain laboratory workers who may work directly with the organism, and some members of the US military.

The vaccine may also be recommended more broadly to exposed community members as a component of a public health response after a bioterrorism event.

Post exposure prophylaxis guidelines

- All individuals with inhalation exposure should be treated for 60 days, regardless of their vaccination status.

- Multiple agents should be used instead of monotherapy

- Quinolones have been approved for inhalational anthrax. Doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are the first line treatment.

- Anthrax meningitis should be managed with triple antibiotics

- Cutaneous anthrax can be treated with doxycycline or a quinolone

- Treatment of pregnant and post partum patients is the same as non pregnant females.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of inhalational anthrax includes community-acquired pneumonia, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, pneumonic plague, and tularemia. The differential diagnosis of cutaneous anthrax includes staphylococcal skin abscess, cat scratch disease, tularemia, spider bite, and ecthyma gangrenosum. Additional GI anthrax differential diagnostic considerations include ulceroglandular tularemia or bubonic plague.

Prognosis

The majority of cases of anthrax have been cutaneous and these usually resolve with or without treatment. If treated promptly with antibiotics, the mortality rate is less than 2%. However, inhalational anthrax is life-threatening and carries a poor prognosis. Even with adequate treatment, mortality rates of 50% have been reported.

Deterrence and Patient Education

- For post-exposure prophylaxis, use a quinolone and doxycycline for at least 4 weeks

- The monoclonal antibodies oblitoxaximab and raxibacumab are indicated when inhalation exposure is suspected. They should be used in combination with the antibiotics

- The vaccine is administered in 3 doses over 4 weeks

Pearls and Other Issues

A bioterrorist attack occurred in the United States in 2001, resulting in inhalational anthrax in 11 people and 5 deaths, and cutaneous anthrax in another 11 people. In response, the United States has prepared a medical countermeasures strategic national stockpile of antimicrobials, antitoxins, and vaccine.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Anthrax is a serious infection which can rapidly prove fatal. Anthrax is very rare and when it occurs, one should suspect bioterrorism. All healthcare workers including nurses, pharmacists, physician assistants, and physicians must be aware that anthrax has the potential to be used as an agent of terrorism. Because of the potential to cause death rapidly, the disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that is dedicated to the treatment of bioterrorism.

The an interprofessional team should be vigilant in evaluating for the possibility of anthrax when multiple patients present with similar symptoms. Anthrax is a reportable infection and the local authorities including the CDC must be immediately notified. The laboratory personnel must be told about the possibility of anthrax so that they can use appropriate protection when performing analysis. The pharmacist must be aware of CDC guidelines on drugs to treat anthrax and when to use the vaccine.

In the event of a bioterrorism attack, mass post-exposure prophylaxis with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline may be recommended with public health guidance. As a preventive for inhalational anthrax post-exposure, duration of antibiotic therapy is 60 days to prevent relapse from ungerminated spores in the lungs.

When caring for anthrax patients, the interprofessional team should work together to maintain standard hospital universal precautions should be utilized with attention to using contact precautions for draining cutaneous lesions.[10][11] Unlike many other infections, with anthrax, the fewer the people involved in the care of the patient, the less likely is there a chance of contamination and transmission of the infection to others. Hand washing must be rigidly adhered to.

The patient needs to be in isolation and only a few select nurses and clinicians should be in charge. Signs should be posted to ensure that everyone is aware of the disorder. All patient body fluids and blood samples should be clearly labeled. Clothing should be decontaminated and all spills cleaned with bleach.

The nurses and clinicians should work together to educate the patient and family in regards to the condition. The best outcomes will occur if an interprofessional team approach is used to evaluate and treat patients with an anthrax infection. [Level V]