Continuing Education Activity

Ankle fractures are among the most common orthopedic injuries, presenting challenges due to their complexity and the potential involvement of multiple structures, including bones, ligaments, nerves, and blood vessels. This activity reviews acute ankle fracture evaluation, classification, and management. Participants learn to apply classification systems to understand injury mechanisms, assess neurovascular status, interpret imaging modalities, and determine surgical versus nonoperative management strategies. The course emphasizes the importance of timely intervention, accurate diagnosis, and interprofessional collaboration to minimize complications, optimize outcomes, and restore ankle function while addressing variations in fracture patterns across age groups and injury mechanisms.

Objectives:

Identify and describe various mechanisms of ankle fractures.

Evaluate the different types of ankle fractures.

Assess the treatment options for acute ankle fractures.

Communicate interprofessional team strategies to enhance care delivery and improve patient outcomes with acute ankle fractures.

Introduction

Ankle fractures are common injuries that could result from a range of mechanisms, such as a trivial twisting in frail adults up to high-energy trauma in the young population. Treatment of ankle fractures aims to restore joint alignment and stability to reduce the risk of post-traumatic ankle arthritis.[1][2]

Anatomy of the Ankle Joint

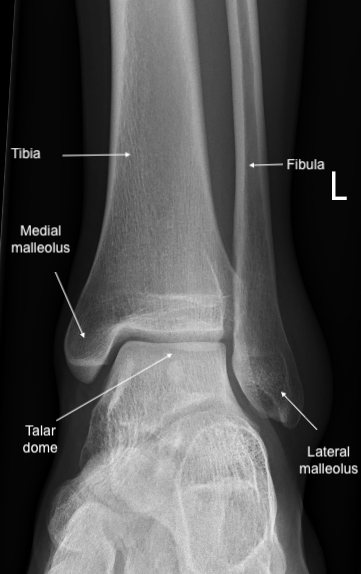

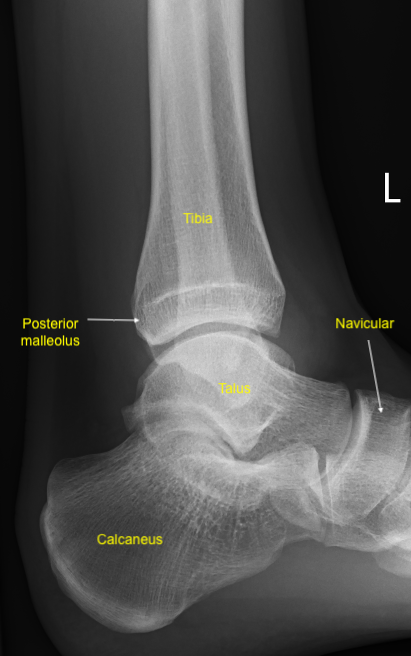

The ankle joint is a hinged, synovial joint that moves in one plane to produce dorsiflexion and plantar flexion.[3] The joint is formed by 3 articulating bones: the distal tibia, distal fibula, and the talus. The articular surfaces of the distal tibia and fibula form the ankle mortise, which contains the body of the talus inferiorly.[3] The ankle joint has 3 malleoli: the lateral malleolus of the distal fibula and the medial and posterior malleoli of the distal tibia. The ankle mortise articulation provides ankle joint stability with the body of the talus, ankle syndesmosis, ligaments, and muscles around the ankle joint. The ankle syndesmosis is a fibrous joint connecting the distal tibia and fibula. The syndesmosis is formed by 3 main parts: the interosseous tibiofibular ligament, the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament, and the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament.[4] The deltoid ligament originates from the medial malleolus and attaches to the talus, navicular, and calcaneus bones. The deltoid ligament stabilizes the ankle joint against over-eversion.[5] The lateral ligament complex consists of 3 ligaments originating from the lateral malleolus. This ligament attaches to the talus through the anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments and the calcaneus through the calcaneofibular ligament. The lateral ligament complex resists over-inversion.[5] Articular branches of the tibial nerve and the superficial and deep peroneal nerves innervate the ankle joint structures. Branches from the peroneal, anterior, and posterior tibial arteries provide the blood supply to the ankle joint.[6]

Etiology

Ankle fractures can be caused by various types of trauma, such as twisting, impact, and crush injuries. Falling, tripping, or sports activities may lead to twisting forces through the ankle. Impact injuries can occur from a fall from height, resulting in impaction of the distal tibia and fibula against the talus. An ankle crush injury may result from a road traffic accident or the ankle being trapped under a heavy object. The degree of bony comminution and soft tissue damage is directly related to the energy of the trauma.

Epidemiology

About 187 per 100,000 adults sustain ankle fractures every year.[7] The incidence in the female population is highest in ages 75 to 84, compared to 15 to 24 years for males.[8] Isolated unimalleolar fractures are the most common, accounting for 70% of the yearly incidence of all ankle fractures. About 20% of ankle fractures are bimalleolar, while trimalleolar fractures represent about 7% of all ankle fractures annually. The incidence of open ankle fractures is approximately 2%.[8]

Pathophysiology

The ankle joint's bony and ligamentous structures form a complete ring. When the ring is broken, it happens in 2 places. A full assessment of the ankle ring is necessary to avoid missing any bony or ligamentous injuries. Several systems have been developed to classify ankle fractures.

Anatomical classification categorizes ankle fractures depending on the anatomical location into the following:

- Isolated medial malleolus fracture

- Isolated lateral malleolus fracture

- Bimalleolar ankle fracture: In this type, 2 malleoli are fractured, either the medial and lateral malleoli or the poster and lateral malleoli, which is less common.

- Trimalleolar ankle fracture: The 3 ankle malleoli (medial, lateral, and posterior) are broken.

Danis-Weber classification categorizes ankle fractures based on the localization of the distal fibula fracture line relative to the syndesmosis into 3 types:

- Weber type A: The distal fibula fracture is located below the level of the syndesmosis. This type of fracture is typically stable and can often be treated conservatively.

- Weber type B: The distal fibula fracture occurs at the same level as the syndesmosis. This type of injury may be treated conservatively if stable (ie, without deltoid ligament injury or syndesmotic injury), but unstable Weber Type B fractures require surgical fixation.

- Weber type C: The fibula fracture is located above the level of the syndesmosis. This type of fracture is usually unstable and requires surgical fixation.[9]

The Lauge-Hansen Classification is based on the foot's position and the direction of the force that causes the injury. This classification categorizes ankle fractures into 4 types. The first word of each type describes the foot position at the time of the injury, and the second word describes the movement of the talus in ankle mortise relative to the tibia. When the foot is pronated, medial ligaments are stretched and prone to injury. When the foot is supinated, lateral ligaments are stretched and prone to injury.[10] The 4 categories are listed below.

- Supination-adduction (SA)

- Distal fibula transverse fracture

- Medial malleolus vertical fracture

- Supination-external rotation (SER) - most common ankle injury (60% fractures)

- Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament injury

- Spiral (or oblique) fracture of the distal fibula

- Posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament injury or posterior malleolus avulsion

- Fracture of medial malleolus or deltoid ligament injury

- Pronation-external rotation (PER)

- Fracture of medial malleolus or deltoid ligament injury

- Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament injury

- Spiral (or oblique) fracture of the fibula (aspect proximal to tibial plafond)

- Posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament injury or posterior malleolus avulsion

- Pronation-abduction (PA)

- Fracture of medial malleolus or deltoid ligament injury

- Anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament injury

- Comminuted or transverse fibular fracture (proximal to tibial plafond)

Injuries occur in a cumulative pattern. For example, a SER4 includes injuries in SER1, SER2, and SER3 categories.[10]

Other Types of Ankle Fractures

- Maisonneuve injury is an unstable ankle injury caused by pronation and external rotation injury. Maisonneuve injury combines a proximal fibular fracture with tibiofibular syndesmosis and deltoid ligament injury with or without medial malleolus fracture. This unstable injury requires operative treatment.[11]

- Pilon fracture is the comminuted fracture of the tibial plafond, which is the distal end of the tibia, including the articular surface. Pilon fracture usually results from high-energy axial loading trauma, eg, a fall from a height that causes impaction of the talus against the tibial plafond.[12]

- Bosworth fracture-dislocation is a rare type of ankle fracture dislocation where the fibula is dislocated posteriorly. The posterior tibial border blocks the fibula from reduction; therefore, operative treatment is required to reduce and fix the fibula in the incisura fibularis (fibular notch).[13]

History and Physical

A complete patient history is an integral part of any medical evaluation. The clinician needs to cover all of the following:

Medical background: Comorbidities that affect the prognosis of ankle fractures include diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, peripheral neuropathy, inflammatory joint diseases, obesity, and kidney diseases. Uncontrolled diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, and peripheral neuropathic disorders affect fracture and surgical wound healing and increase the risk of Charcot's joint. If indicated, all medical and systemic diseases should be addressed and optimized before the surgery.

Social history: The social history should establish a patient's functional baseline and goals. The patient’s level of mobility before injury, home situation (physical layout and assistance available), regular activities, and functional goals should be discussed. Patients should be educated that smoking and alcohol overuse can complicate wound and fracture healing.

History of the injury: Identifying the mechanism of injury is crucial for understanding its nature and severity. A higher-energy mechanism should raise concerns about compartment syndrome of the leg or a more grave injury such as a pilon fracture (axial loading). The ankle position at the time of injury and subsequent direction of force generally dictate the fracture pattern, as described by the Lauge-Hansen classification system.

Venous thromboembolism risk assessment: This should be completed for all patients who sustain ankle fractures to identify the risk factors for developing deep venous thrombosis. Risk factors include but are not limited to smoking, previous deep venous thrombosis, family history of deep venous thrombosis, high body mass index, active participation in hormonal therapy, and use of oral contraceptive pills. Patients who are at high risk for venous thromboembolism should receive the appropriate prophylaxis treatment.

Evaluation

Clinical Assessment

1. Adult trauma life support (ATLS) primary and secondary survey

All trauma patients should be assessed according to trauma assessment principles. The primary ATLS survey should be completed in order from A to E to rule out any life-threatening injuries:

- A: Airway management and cervical spine stabilization

- B: Breathing

- C: Circulation and hemorrhage control

- D: Disability (neurologic status)

- E: Exposure [14]

2. Neurovascular assessment

A neurovascular assessment must be performed and documented before and after any attempt at ankle manipulation. The color and temperature of the foot should be assessed. A pale, cold foot indicates a critical vascular compromise. Dorsalis pedis posterior tibial pulses should be assessed and compared to the contralateral side. If there is any clinical concern for vascular compromise or skin tenting, urgent ankle reduction should be attempted immediately to regain vascular flow, followed by neurovascular reassessment. Hand Doppler ultrasound is a quick and noninvasive method to assess the vascular flow in the foot. Neurological assessment should include the motor and sensory function of the deep peroneal, superficial peroneal, tibial, sural, medial, and lateral plantar nerves.

3. Soft tissue assessment

Threatened skin in a deformed ankle necessitates urgent reduction and splinting to minimize soft tissue stretching. The timing of surgical fixation is influenced by the integrity of the soft tissues and the degree of swelling present.

4. Examination of the proximal fibula

A thorough examination of the proximal fibula and the knee joint is essential to ensure no higher injuries, such as a Maisonneuve fracture, are overlooked. The Maisonneuve fracture occurs at the proximal fibula and is often associated with syndesmotic injury at the ankle.

Ottawa Ankle Rules

Ankle radiographs should be requested when a patient presents with pain or tenderness in either malleolus, accompanied by at least 1 of the following criteria:

- Tenderness at the bone: There is tenderness at the posterior edge or tip (within 6 cm) of the lateral or medial malleolus. This localized tenderness may indicate a fracture or significant injury to the bony structures surrounding the ankle.

- Inability to bear weight: The patient is unable to bear weight both at the time of injury and upon arrival at the emergency department. Weight-bearing is assessed by the patient’s ability to take at least 4 steps independently. The inability to bear weight is a critical indicator of higher injury severity and necessitates further imaging to evaluate for fractures or other injuries.[15]

Imaging Modalities

1. Plain radiographs

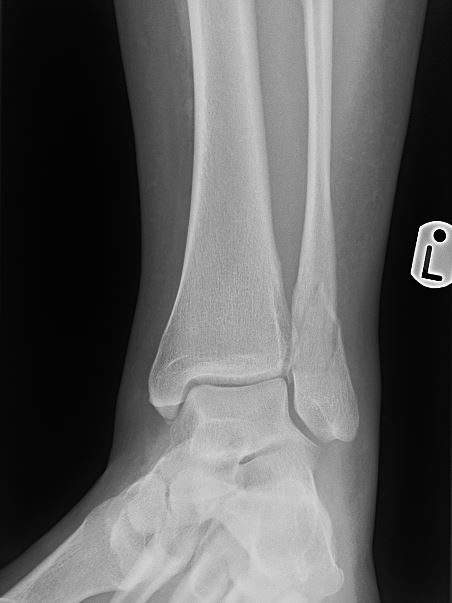

Plain radiographs (x-rays) are taken early to assess ankle injuries. While obtaining x-rays is important, it should not delay the reduction of a clinically obvious ankle deformity, as these injuries are time-sensitive. The recommended x-ray views for evaluating ankle injuries include the anteroposterior, lateral, and mortise views.

- The anteroposterior ankle view is useful for assessing soft tissue swelling, which may reveal more subtle fractures that might otherwise go unnoticed.

- The lateral ankle view provides crucial information about the posterior malleolus and the talar dome in relation to the distal mortise. This view is essential for determining whether the talus is dislocated anteriorly or posteriorly.

- The mortise view is particularly important for evaluating the ankle mortise, which consists of the tibial plafond, medial and lateral malleoli, and the talar dome.[16] To obtain this view, the leg should be internally rotated 15 to 20 degrees while the ankle is dorsiflexed. This positioning allows for a clear assessment of talus alignment and syndesmosis widening. The mortise joint space should be uniform in a healthy ankle.

- In addition to these standard views, weight-bearing and external rotation stress views may be indicated to assess fracture stability and to rule out deltoid ligament and syndesmotic injuries. Furthermore, obtaining full-length x-rays of the tibia and fibula is valuable for ruling out proximal fibula fractures associated with a Maisonneuve injury.

2. Computed tomography scan

A computed tomography scan is valuable for evaluating complex ankle injuries and provides detailed information about the articular surfaces, fracture configurations, and the degree of bone comminution. This level of detail is crucial for accurately assessing the injury's extent and determining the best surgical approach.[17]

Computed tomography scans are often used for operative planning of complex ankle fractures, where conventional x-rays may not provide sufficient detail. Surgeons can devise a more precise and effective treatment strategy by visualizing the intricacies of the fracture pattern, including the involvement of the joint surface and surrounding structures. High-resolution imaging can also aid in identifying other subtle injuries that may have been missed on x-ray, ensuring comprehensive surgical intervention.

In addition to operative planning, computed tomography scans are useful for assessing posterior malleolar fractures. These fractures can significantly impact ankle stability and function, making it essential to understand their characteristics. The computed tomography scan can reveal the size, orientation, and displacement of posterior malleolar fractures, enabling surgeons to make informed decisions regarding fixation techniques and the need for additional stabilization.[17]

3. Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluating ligamentous and other soft tissue conditions of the ankle. MRI's high-resolution images allow for detailed visualization of both bony and soft tissue structures, making it particularly useful in the following scenarios:

- Deltoid ligament sprain: MRI can effectively assess the integrity of the deltoid ligament, which is crucial for stabilizing the medial aspect of the ankle. MRI can help determine the severity of the sprain and identify associated injuries.

- Lateral ligament complex sprain: MRI can also evaluate injuries to the lateral ligament complex, including the anterior talofibular ligament, calcaneofibular ligament, and posterior talofibular ligament. This imaging helps ascertain the extent of the sprain and guides management decisions.

- Syndesmotic disruption: MRI is particularly useful for diagnosing syndesmotic injuries involving the ligaments connecting the distal tibia and fibula. These injuries can significantly impact ankle stability and may require specific treatment approaches.

- Chondral lesions: MRI can detect chondral lesions or damage to the cartilage surface within the ankle joint. Identifying these lesions is important for understanding the potential for post-traumatic arthritis and determining appropriate treatment strategies.

- Stress fractures: MRI is also effective in diagnosing stress fractures, which may not be visible on standard x-rays. MRI can reveal bone edema and other changes associated with stress fractures, aiding in early diagnosis and management.

Treatment / Management

Ankle fracture treatment aims to restore stability in the ankle mortise. Unstable fractures are generally treated surgically, whereas stable fractures may be adequately addressed with conservative treatment.[18]

Nonoperative Treatment

Indications

- Stable ankle fractures, eg, isolated unimalleolar ankle fracture with no talar shift on weight-bearing ankle x-rays

- Patient unfit for or refusing surgery

- Poor soft tissue conditions

Nonoperative treatment methods

- Below knee cast

- Fracture reduction and application of a close contact cast under image guidance could be a valid option for unstable ankle fractures in patients above 60 or who are unfit for surgery.[19]

- Walking boot

- Proper pain control

Operative Treatment

Open reduction and internal fixation

Urgent open reduction of an ankle fracture-dislocation may be necessary if attempts at closed reduction have failed or if there is a neurovascular deficit. Ankle fracture open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is typically indicated for patients with an unstable ankle mortise who are fit for surgery and have favorable soft tissue conditions. Surgical fixation is usually performed within 24 hours of injury but can wait a few days if the surgeon wants to allow soft tissue swelling to subside to reduce the risk of wound dehiscence. Ankle fracture ORIF is an appropriate treatment for the following:

- Unimalleolar fractures with talar shift observed on weight-bearing ankle x-rays

- Bimalleolar ankle fractures

- Trimalleolar ankle fractures

- Pilon fractures

- Maisonneuve fractures

Fibular fractures can be stabilized using plates and screws or fibular nails. Fibular nails are particularly suitable for comminuted fractures with poor bone quality. Transverse medial malleolus fractures can be fixed using partially threaded screws or tension band wiring to create compression at the fracture site. In contrast, vertical medial malleolus fractures require buttressing fixation with an anti-glide plate.

Posterior malleolus fractures can be addressed with a posteroanterior lag screw or an antiglide plate. Intraoperative assessment of the ankle syndesmosis is essential and can be performed using the Hook test (Cotton test) or intraoperative stress external rotation views to confirm proper alignment and stability.[20][21] The Hook test can be performed by the lateral distraction of the fibula with a bone hook under the image intensifier screen. The Hook test is considered positive if there is more than 2 mm of displacement of the fibula.[22] If the hook test is positive and there is a syndesmosis diastasis, the syndesmosis should be reduced by applying a big reduction clamp to the medial and lateral malleoli and then fixed either by syndesmotic screws or tightropes.

Spanning external fixator

External fixation is often indicated as a temporary stabilization technique for unstable ankle fractures, particularly in cases of severe soft tissue swelling or open fractures. This method helps maintain the ankle mortise in an optimal position, allowing time for soft tissue healing and swelling reduction until definitive surgical repair is indicated. External fixators provide a safer environment for subsequent surgical intervention and optimize tissue alignment to aid healing.

Once soft tissues have adequately healed, a second-stage procedure, such as ORIF, can be performed to repair the ankle fracture definitively. During the application of external fixation, it is essential to plan for the definitive surgical approach. Pins should be carefully positioned away from the anticipated incision sites for ORIF to avoid complications during the second-stage surgery and to maintain clear surgical access.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating ankle fractures from other traumatic foot and ankle conditions is crucial, as these injuries can present with similar symptoms but necessitate distinct management approaches.

Deltoid Ligament Sprain

A deltoid ligament sprain typically presents with tenderness and swelling over the medial malleolus. Patients may experience pain when bearing weight. Weight-bearing ankle x-rays may reveal a shift of the talus, indicating instability. An MRI scan provides detailed images of soft tissue structures to help confirm a deltoid ligament sprain.

Lateral Collateral Ligament Complex Sprain

A lateral collateral ligament complex sprain presents with tenderness and swelling over the lateral malleolus, commonly resulting from an inversion injury. Like deltoid ligament injuries, severe ligament damage may result in talar shifting visible on weight-bearing x-rays. MRI imaging is useful for evaluating the lateral ligament complex, including the anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments and the calcaneofibular ligament, to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of injury.

Achilles Tendon Rupture

Patients with Achilles tendon rupture often report a sudden, sharp pain or a sensation of a snap at the back of the ankle. A palpable gap may be present on examination of the tendon. The Simmonds (Thompson) test assesses the tendon's structural integrity. The Simmonds test is performed in the prone position with the knee flexed. The examiner squeezes the belly of the calf muscle to simulate muscle contraction. If the tendon is intact, this will result in ankle plantarflexion (a negative Simmonds test). If the Achilles is completely ruptured, plantarflexion does not occur (a positive Simmonds test). Ultrasound is valuable for assessing the degree of rupture, determining the tendon gap, and planning treatment accordingly. X-rays are typically unremarkable.

Prognosis

The prognosis for stable nonsurgical ankle fractures is excellent. These individuals can gradually resume weight-bearing activities as tolerated and may return to their baseline level of function within approximately 6 to 8 weeks postinjury. Patients with unstable fractures requiring ORIF begin full weight-bearing around 6 to 8 weeks postsurgery. However, full recovery may take longer due to more extensive tissue damage and longer immobilization. Despite anatomical reduction and stable fixation, about 14% of ankle fractures may lead to posttraumatic arthritis of the ankle joint. This complication is thought to be related to underlying chondral injuries sustained at the time of the fracture.[23]

Complications

Complications following ankle fractures can occur after both conservative nonoperative management and operative management.[24]

Nonoperative management complications may include:

- Ankle stiffness

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Ankle mortise redislocation

- Skin ulceration due to cast pressure

- Fracture delayed union

- Fracture non-union

- Fracture malunion

- Ankle chronic instability

- Delayed return to functional activity

- Ankle arthritic changes

Operative management complications may include:

- Infection

- Painful scar

- Wound dehiscence

- Metalwork failure (eg, broken plate or loose screw )

- Mal-positioned metal work (eg, screw protrusion into the joint)

- Prominent screws

- Fracture non-union

- Fracture delayed union

- Nerves damage

- Vascular damage

Charcot Arthropathy

Neuropathic arthropathy, also called Charcot arthropathy, is a significant complication of ankle fracture in individuals with diabetes. Diabetic neuropathy can cause loss of sensation in the lower limb, making recognizing injurious stresses difficult. Consequently, patients tend to experience progressive trauma in the ankle and foot due to a lack of recognition of the problem. Joint degeneration is characterized by increased bone resorption and the destruction of bone. This ultimately results in alterations in the normal alignment of the ankle, joint deformities, and instability.

The long-term consequences of Charcot arthropathy can be severe. Patients may develop ulcerations on the foot due to the altered biomechanics and pressure distribution resulting from joint deformities. These ulcers can become infected, leading to serious complications, including cellulitis or osteomyelitis. In some cases, if infections are not adequately managed or if the ulcerations do not heal, patients may face the possibility of amputation. Healthcare providers must be vigilant in monitoring patients with diabetes for signs of Charcot arthropathy following an ankle fracture. Early detection and intervention are essential to manage the condition effectively and prevent further complications. Treatment may involve offloading the affected joint, physical therapy, and, in some cases, surgery to restore stability and function.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education is a crucial component of care for patients with ankle fractures. Expectations for the course of healing and potential complications such as increased pain, swelling, or changes in sensation should be explained. Providing this information empowers patients to take an active role in their recovery and ensures timely medical attention if complications arise. Patients should be educated on the role of physical therapy to assist in symptom management and timely restoration of flexibility, strength, and weight-bearing tolerance to restore a healthy gait pattern to optimize outcomes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about ankle fractures are as follows:

-

Completing the ATLS primary survey is crucial for identifying and managing life-threatening injuries. Once the initial assessment is complete, the secondary survey should follow, which includes a thorough examination of the affected limb. This examination must encompass a detailed assessment of the soft tissues and neurovascular status to evaluate for damage.

-

In cases of ankle fracture-dislocation, urgent manipulation is necessary to restore proper alignment.

-

Appropriate imaging studies assist in accurate diagnosis and guide management strategies. Assessing the neurovascular status of the ankle before and after reduction and splinting is crucial to ensure proper blood flow and nerve function.

-

Accessory ossicles may be present in the joint due to normal anatomical variations. In trauma cases, these ossicles can be mistaken for avulsion fractures, underscoring the need for careful imaging interpretation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Emergency room management of patients with ankle fractures requires a multidisciplinary approach. Those who experience high-energy trauma, such as road traffic accidents or falls from a height, require the involvement of the entire trauma team and should be managed in a trauma call setting per ATLS principles. The presence of ankle fractures mustn't distract clinicians from identifying and addressing potentially life-threatening injuries, such as hemothorax or internal organ damage. The trauma team should consist of a trauma leader, an emergency department physician, a general surgeon, an anesthesiologist, a trauma radiographer, and 2 nurses to ensure comprehensive care and effective management of the patient’s condition.[14]

Effective communication among team members is critical when procedural sedation is necessary for reduction. For patients with unstable fractures requiring surgery, the orthopedic team must promptly develop a plan for definitive fixation based on the condition of the soft tissues. While hospitalized, physical therapists play a crucial role in helping patients enhance their range of motion, strength, and weight-bearing capabilities.

Before discharge, patients, case managers, and medical staff should work together to develop the discharge plan. First, the discharge destination of home versus rehabilitation center must be established, followed by coordinating the necessary equipment (such as assistive devices and dressing aids), home nursing services, and prescriptions for thromboprophylaxis. If discharged home, the patient should be referred to outpatient or home health physical therapy for rehabilitation. Additionally, appropriate follow-up appointments should be scheduled for the patient to be evaluated by the orthopedic team to monitor progress and recovery.