Continuing Education Activity

Myelophthisic anemia is a normocytic type of anemia characterized by immature erythrocytes in the peripheral blood due to abnormal tissue infiltrating the bone marrow. It is also a hypo-proliferative anemia because it results from inadequate production of red blood cells from the bone marrow. This activity reviews the cause and presentation of myelophthisic anemia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

Assess the cause of myelophthisic anemia.

Identify the peripheral blood smear in a patient with myelophthisic anemia.

Evaluate the treatment of myelophthisic anemia.

Communicate modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by myelophthisic anemia.

Introduction

Anemia is reduced hemoglobin, red blood cells, or hematocrit levels below their lower normal range. There are different types and causes of anemia. Anemia is subdivided into microcytic, macrocytic, and normocytic variants. Myelophthisic anemia is categorized under the normocytic variety of anemia. Normocytic anemia has the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) within the normal range of 80 to 100 fL. Other types of normocytic anemia apart from myelophthisic anemia include aplastic anemia, anemia of chronic disease, and anemia of renal disease. Microcytic anemia is MCV below 80 fL, including sideroblastic anemia, iron deficiency anemia, and thalassemia. The macrocytic anemias have MCV greater than 100 fL, including megaloblastic and non-megaloblastic anemia. Anemia can be asymptomatic or can present with mild to severe symptoms. Severe symptoms can be devastating since they can limit the functional capacity of the individual to carry out even basic activities of daily living. A recent article by Kassebaum NJ et al reported that about 27% of the world population is affected by anemia, with iron deficiency anemia being the most common subtype implicated.[1] Anemia considerably affects morbidity and mortality; thereby, it is of the utmost relevance in making timely diagnoses and undertaking effective treatment.

Myelophthisic anemia is characterized by immature erythrocytes in the peripheral blood due to abnormal tissue infiltration (crowding out) of the bone marrow. It is a hypo-proliferative variant of anemia because it results from inadequate production of red blood cells from the bone marrow.[2] Hypoproliferative anemia differs from other forms since the reticulocyte count is usually low compared to anemia caused by increased blood loss or peripheral destruction, wherein the reticulocyte count mostly increases. Other causes of hypo-proliferative anemia include nutritional deficiencies, toxin exposures, endocrine abnormalities, hematologic malignancies, and bone marrow failure syndromes.[2] This topic focuses on myelophthisic anemia and its epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, complications, evaluations, and management.

Etiology

Myelophthisic anemia results from fibrosis and crowding out of the normal bone marrow owing to infiltration by non-hematopoietic or abnormal cells such as metastatic cancers or hematologic malignancy, granulomatous lesions, lipid storage diseases, and primary myelofibrosis. Several cases of breast, prostate, and hematological cancers have been reported to cause bone marrow infiltration. Khan et al reported a similar case of lobulated breast cancer infiltrating the bone marrow.[3] These space-occupying cancers replace hematopoietic stem cells, resulting in pancytopenia and extramedullary hematopoiesis.[3] Fibrosis of the bone marrow can also result from disseminated mycobacterial infection, autoimmune diseases, renal osteodystrophy, hypo, or hyperthyroidism.[2]

Epidemiology

Myelophthisic anemia is reported in less than 10% of patients with metastatic cancers such as prostate, breast, and lungs.[4]

Pathophysiology

Research has implicated proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alfa and interleukins in inducing fibroblastic proliferation, thereby leading to marrow fibrosis.[5]

Histopathology

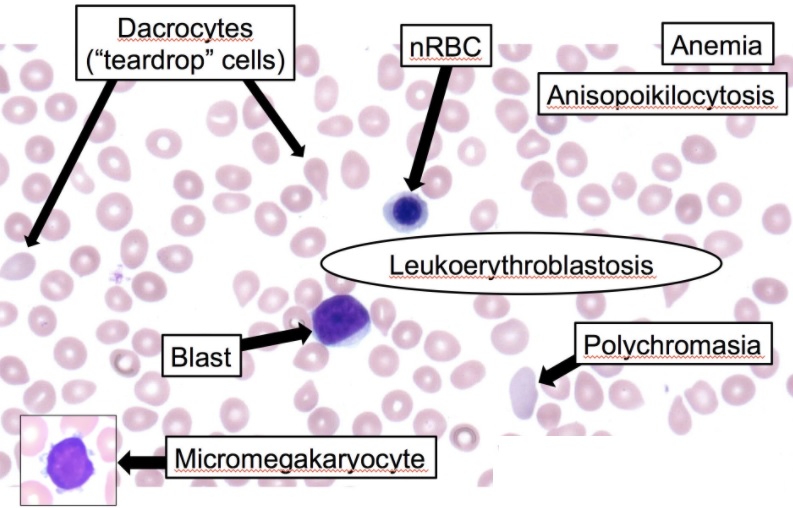

In myelophthisic anemia, the peripheral blood smear shows characteristic leukoerythroblastic reactions with the presence of immature myeloid and nucleated erythrocytes, including abnormal erythrocytes such as schistocytes and dacrocytes (teardrop) and anisopoikilocytosis cells (see Image. Leukoerythroblastosis Reaction in the Peripheral Smear). These are secondary to extramedullary hematopoiesis and the disruption of marrow sinusoids. Since there may be a dry tap during bone marrow tap owing to fibrosis, bone marrow biopsy is essential for diagnosing and visualizing underlying etiologies such as metastatic cancer cells or granulomatous lesions.

History and Physical

Patients with myelophthisic anemia have a history of underlying malignancy or chronic inflammatory or infectious diseases. Malignancies that have correlations with myelophthisic anemia include prostate, breast, and lung carcinomas. Reports also exist of myelophthisis in patients with advanced-stage melanoma.[6] Patients have symptoms of anemia, including fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance. On physical examination, the patient has conjunctiva pallor, delayed capillary refill, tachycardia, and splenomegaly. Splenomegaly, as well as hepatomegaly, is found in this type of anemia because of the development of extramedullary hematopoiesis due to the failure of the bone marrow to produce matured erythrocytes. These patients also have increased risks for bleeding tendencies (thrombocytopenia) as well as repeated infections (leukopenia).

Evaluation

The combinations of relevant laboratory data, peripheral blood smear, and bone marrow biopsy should be studied to recognize and appropriately diagnose myelophthisic anemia. Laboratory data include a complete blood count, which shows the level of white blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets, MCV, reticulocyte counts, and red cell distribution width. In myelophthisic anemia, pancytopenia could be found due to infiltration by cancers and also fibrosis. MCV is usually normal in this type of cancer, and reticulocyte counts are low. A peripheral blood smear shows abnormal red blood cells ranging from immature to defective shapes and the size of the cells. Red blood cells be nucleated, and some be in teardrop forms. Other cells include giant platelets and immature leucocytes. The presence of these immature cells is called leucoerythroblastic.[7] Bone marrow biopsy shows signs of infiltration by primary cancer and fibrosis in cases secondary to granulomatous infections or autoimmune diseases.[4]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of myelophthisic anemia is variable because it has as its basis the underlying etiology. For patients with malignancies, treating and getting rid of the malignant tissue through chemotherapy or radiation helps eliminate the infiltrating tissue, taking the space of hematopoietic cells. Rosner et al (2013) reported a case report where an advanced staged melanoma causing myelophthisis responded to immune checkpoint inhibition with the anti-programmed cell death-1 inhibitor or PD-1 inhibitor, pembrolizumab.[6] They reported a favorable response after using this PD-1 inhibitor. As a result of the reaction of the melanoma to a PD-1 inhibitor, they believe there is an immunologic compartment within the bone marrow. Other clinicians have also reported an interaction between immune and skeletal systems implicating the pathogenesis behind such an entity.[8] Because a patient with myelophthisic anemia has low hemoglobin levels, transfusion of packed red blood cells is also indicated. Even though other cell lines are also low, transfusions of platelets or giving leukocytes stimulating medication are also not indicated unless there is severe concurrent bleeding or infections. For a patient with myelophthisic anemia following primary myelofibrosis, a study demonstrated survival benefits from using ruxolitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of myelophthisic anemia includes other causes of hypo-proliferative anemia. Before diagnosing myelophthisic anemia, it is essential to rule out nutritional deficiencies like iron, vitamin B12, and folate deficiencies, anemia of chronic disease and inflammation, anemia of renal disease, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hematologic malignancies and other causes of bone marrow failure. Bone marrow failure can be due to various etiologies, including drugs, infection, immune diseases, pregnancy, and some genetic diseases. Drugs that could cause this presentation include cytotoxic drugs such as those used in chemotherapy. Infections such as parvovirus B19 and EBV have also been reported to mimic myelophthisic anemia. Genetic causes that should be ruled out include Fanconi anemia, GATA 2 deficiency, and Schwachman-Diamond syndrome, as they also cause pancytopenia. Anemia is multifactorial, and it could be challenging to come up with a diagnosis of myelophthisic. However, the careful evaluation of peripheral smear, bone marrow biopsy, and immunohistochemistry help in coming up with the diagnosis.[4] Leukoerythroblastosis in the setting of extramedullary erythropoiesis is crucial in differentiating this entity from its close counterparts, such as aplastic anemia and pancytopenia.

Prognosis

The prognosis of myelophthisic anemia varies depending on the underlying cause. For instance, in cases of advanced carcinoma, metastases to the bone marrow are a poor prognosis marker. Kwon JI reported that the prognosis of gastric carcinoma is extremely poor when there are metastases to the bone marrow.[10]

Complications

Complications that could occur in these patients are symptoms of severe anemia due to the low volume of normal red blood cells circulating in the peripheral blood, infection due to leukopenia, and excessive bleeding due to pancytopenia. Hypersplenism resulting in refractory thrombocytopenia, as well as portal hypertension, can further complicate these patients.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should be aware that there are different causes and types of anemia. Iron deficiency anemia is the most common cause, and it is treatable with iron supplements. Other types of anemia, such as myelophthisic anemia, require management by treating the underlying cause. The signs and symptoms of anemia will be similar, including fatigue, conjunctiva pallor, tachycardia, and sometimes shortness of breath. Patients should educate themselves and discuss with the primary care physician whenever they develop new symptoms like recurrent bleeding and infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Physicians and nurse practitioners must investigate the cause of anemia in patients with cancer. There have been reports of patients being misdiagnosed owing to their different presenting signs and symptoms. Khan MH et al reported a case of a 57-year-old female with stage 4 lobular breast carcinoma who was initially misdiagnosed as having thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.[3] The diagnosis of myelophthisic anemia requires a thorough algorithmic workup. Infections, mostly granulomatous variants, can also lead to myelophthisis. If there is doubt about the cause, patients require referral to a hematologist for a definitive workup. The management of these patients is to treat the underlying cause first. Managing all anemias, including myelophthisic anemia, requires coordinating an interprofessional healthcare team that includes physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and oncologic pharmacists. This approach guarantees proper diagnosis and optimal care, leading to the best patient outcomes.