Continuing Education Activity

Abetalipoproteinemia is a rare autosomal recessive disorder marked by low or absent levels of plasma cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins, and very-low-density lipoproteins. It should not be confused with a deficiency in beta-lipoproteins. Hallmark symptoms include fat malabsorption, spinocerebellar degeneration, acanthocytosis, and retinitis pigmentosa. This activity reviews the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment considerations of this disease and highlights the role of the collaboration between interprofessional team members.

Objectives:

Explain how abetalipoproteinemia manifests in each of the three main organ systems that it affects.

Describe anticipated laboratory findings of a patient with abetalipoproteinemia.

Outline the treatment of abetalipoproteinemia.

Review the importance of collaboration between interprofessional team members for improved recognition and treatment of abetalipoproteinemia.

Introduction

Abetalipoproteinemia (ABL) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder marked by low or absent levels of plasma cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs). It should not be confused with a deficiency in beta-lipoproteins. Hallmark symptoms include fat malabsorption, spinocerebellar degeneration, acanthocyte red blood cells, and retinitis pigmentosa. [1][2]

Treatment aims to arrest the neuropathy and efficiency-induced complications in patients.

Etiology

Abetalipoproteinemia is caused by a homozygous autosomal recessive mutation in the MTTP gene. More than 33 mutations that cause the disease have been identified. The gene codes for microsomal triglyceride protein (MTP) that mediates intracellular chylomicron or VLDL assembly and transport in the intestinal mucosa and hepatocytes. Most of the signs and symptoms of the disease result from a severe deficiency of fats and fat-soluble vitamins, especially vitamin E. It usually presents in infants as failure to thrive, steatorrhea, and abdominal distension and results in spinocerebellar degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa.[3]

Epidemiology

Abetalipoproteinemia occurs in less than 1 in 1 million persons. Consanguineous marriages are strongly implicated. Because it is autosomal recessive, both copies of the gene must be faulty to cause the disease. It occurs in females and males equally. [4]

One particular mutation is more common in people of Ashkenazi (eastern and central European) Jewish descent. This mutation substitutes the protein building block, or amino acid, glycine with a stop signal at position 865 (written as Gly865X or G865X). As a result of this amino acid change, an abnormally small, nonfunctional version of the protein is made. [5]

Pathophysiology

Beta apolipoproteins are very large apolipoproteins. They are critically important for the secretion and formation of chylomicrons (CMs) and VLDL. Abnormalities that impede this process result in abetalipoproteinemia and hypobetalipoproteinemia. [6][7][8]

MTP acts as a chaperone that facilitates the transfer of lipids onto apo B. MTP is found within the lumen of microsomes in the liver and intestinal mucosa and catalyzes the transfer of triglyceride, cholesteryl esters, and phosphatidylcholine between membranes. Lipid transport rates decrease in the order of triglyceride to cholesteryl ester to diglyceride to cholesterol to phosphatidylcholine. Unlike other lipid transfer proteins, MTP is a heterodimer containing subunits of molecular mass 58 and 97 kDa. The large 97-kDa subunit possesses the lipid transfer activity or confers lipid transfer activity on the complex. The large subunit of MTP may be missing in abetalipoproteinemia.

Initial assembly occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum, where apolipoproteins, cholesterol, phospholipid, and triacylglycerides are synthesized and incorporated into lipoprotein particles. The particles are subsequently transported to Golgi and secreted. Each lipoprotein is specific in its lipid composition and the type of apolipoproteins it possesses.

The two beta apolipoproteins are B-100 and B-48. ApoB-100 is carried on VLDL. ApoB-100, synthesized by the liver, is larger than apoB-48, which is made up of 4536 amino acids. Unlike apoB-48, apoB-100 contains the binding site essential for LDL uptake by hepatocyte LDL receptors. ApoB-48 is carried on CMs and is derived from the same gene as apoB-100.[1]

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

These manifestations include diarrhea and fat-soluble vitamin deficiency. They are evident from infancy. Diarrhea may not be a prominent symptom later, though, because patients learn to avoid fatty foods. However, the deficits in fat-soluble vitamins continue because their assimilation and transport depend heavily on the integrity of the apoB pathway. It is worth noting that high-dose vitamin E supplementation only results in marginally increased serum vitamin levels. In contrast, high doses of vitamin-A therapy can achieve normal serum levels. This shows that despite the damaged intestinal absorption, the transport of vitamin A by retinol-binding proteins in serum is not impaired in abetalipoproteinemia.

Hepatic Manifestations

- Hepatomegaly due to hepatic steatosis.

- Possible increase in serum ALTs and ASTs

- Reports of cirrhosis in some patients

Hematologic Manifestations

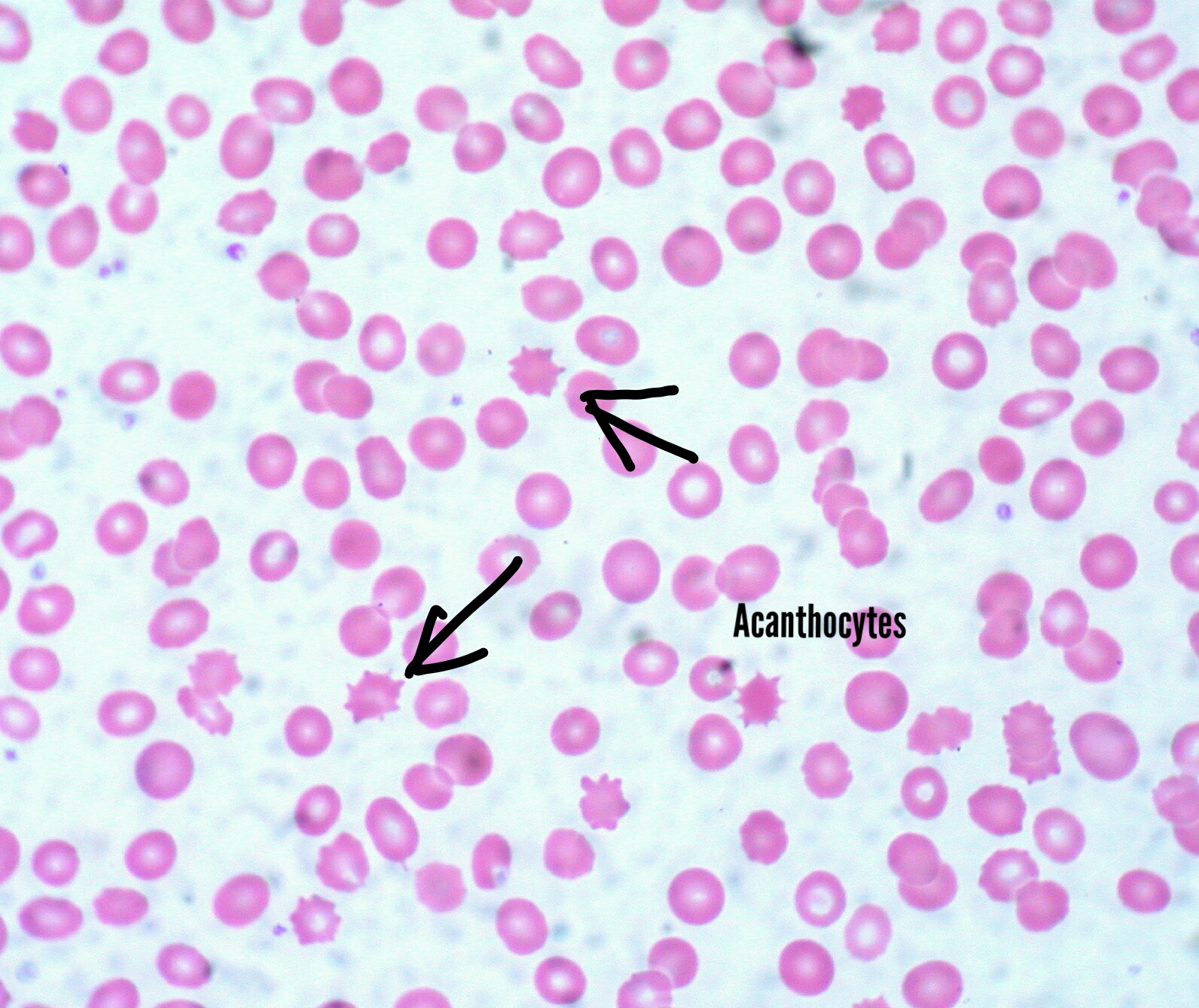

Acanthocytosis is a hallmark feature of this disease. Acanthocytes are abnormally spiked RBCs due to the defective phospholipid cell membrane. They are also seen in liver dysfunction. Because of their inability to form rouleaux, erythrocyte sedimentation rates could be very low. Fat malabsorption could lead to deficiencies in iron, and folic acid, among others, and lead to anemia. Vitamin E is involved in protection from free radical damage. Its deficiency could potentiate lipid peroxidation of cells and lead to hemolysis. This exacerbates anemia. Vitamin K is involved in the gamma decarboxylation of clotting factors, an indispensable step in coagulation. Its deficiency could lead to bleeding disorders.

Neurological Involvement

Peripheral neuropathy, delayed intellectual development, tremor, nystagmus, loss of deep tendon reflexes

These may be myriad and variable in their severity. The primary pathophysiology is demyelination due to deficiency of lipid-soluble vitamins. The central and peripheral nervous systems are both affected.

Muscle Involvement

Weakness and increased degeneration

Ophthalmic Involvement

Retinitis pigmentosa, decreased night and color vision, blindness

Histopathology

Acanthocytes on the peripheral blood smear are seen in abetalipoproteinemia.

History and Physical

Failure to thrive in infancy may cause gastroenterologic, neurologic, and ophthalmologic symptoms, including the following:

Gastroenterology Symptoms

- Steatorrhea and diarrhea

- Abdominal distension

Neurologic Symptoms

- Slow mental growth

- Deep tendon reflexes are absent

- Ataxia

- Slurred speech

- Peripheral neuropathy.

- Intention tremors.

Ophthalmologic Symptoms

- Retinitis pigmentosa by adolescence (due to deficiency of vitamin A)

- Decreased night and color vision.

- Blindness may occur

Evaluation

Complete Blood Count

Complete blood count shows anemia, thrombocytopenia, or pancytopenia.[1]

Blood Smear

Blood smear shows acanthocytes (Burr cells).

Fasting Lipid Profile

Fasting lipid profile shows low VLDLs, LDLs, and total cholesterol.

Stool Study

Stool studies show fat malabsorption and the absence of evidence for other possible causes.

Imaging Studies

- Hepatic scan or ultrasonography to assess changes of fatty liver

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinocerebellar region may show degeneration

- Eye and retinal examination and imaging to check for retinal damage

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Abetalipoproteinemia is a relatively rare genetic and acquired disorder that is characterized by acanthocytic red blood cells, fat malabsorption, spinocerebellar degeneration, and pigmented retinopathy. The condition is associated with very high morbidity, and thus it is vital to have an integrated pathway of management with close interaction with a number of health professionals. Besides a gastroenterologist, an interprofessional approach is essential if one is to improve outcomes:

- Ophthalmologist to regularly assess for retinal degeneration and ophthalmoplegia

- Internist to assess the cholesterol profile and the abetalipoproteinemia.

- Neurologist: to assess and monitor the patient for spinocerebellar degeneration

- Hematologist to assess the anemia and acanthocytosis

- Pharmacist to determine the need for pyridoxine and total parenteral nutrition or supplementation with vitamins

- Dietitian to assess the patient for failure to thrive, assess malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins, and the need to change diet

- Genetic counseling for patients and their first-degree relatives

- Social worker and nurse to assess the patients for nutritional needs, failure to thrive, and referral to a specialist.

Evidence-based Medicine

Because of the rarity of the disorder, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials on the long-term benefits of vitamins. However, small case series and anecdotal reports indicate that when patients are diagnosed and referred early to a clinic that specializes in the management of this lipid disorder, the outcomes are improved.[10] There is ample evidence indicating that prompt supplementation with vitamins can improve the prognosis and outcome.[11] [Level 3] However, the long-term outlook for many of these patients is guarded as many go on to develop vision loss and permanent blindness.