Continuing Education Activity

Apical periodontitis is the local inflammation of the periapical tissues that originate from pulp disease. It may occur due to the advancement of dental caries, trauma, or operative dental procedures. The infected pulp is the main cause of apical periodontitis. The host defense response to pathogenic microbes is what triggers inflammation and the consequent destruction of periradicular tissues. Endodontic disease includes multiple signs and symptoms, both asymptomatic and symptomatic. A thorough evaluation must be completed to determine the source of these symptoms to dictate the appropriate treatment interventions. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of endodontic disease.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology and pathophysiology of apical periodontitis.

- Describe the history and physical presentation of acute and apical stages of apical periodontitis.

- Explain the evaluation and management of apical periodontitis.

- Summarize possible complications of apical periodontitis.

Introduction

Apical periodontitis is the local inflammation of the periapical tissues that originate from pulp disease.[1] It may occur due to the advancement of dental caries, trauma, or operative dental procedures.[2] The infected pulp is the main cause of apical periodontitis. The host defense response to pathogenic microbes is what triggers inflammation and the consequent destruction of periradicular tissues.

Apical diseases can manifest with various clinical presentations, ranging from no obvious clinical signs or symptoms to severe destruction of the underlying bone, with or without a draining abscess. Therefore, proper identification, diagnosis, and treatment of apical diseases can prevent severe clinical signs and symptoms.

Etiology

Dental pulp tissue, the softest and most easily compromised internal structure of healthy dental tissues, is protected by enamel, the dense mineralized outer tooth structure, and intact periodontium, composed of the periodontal ligament, surrounding alveolar bone, and gingival tissue. Bacteria can enter the pulp through cracks, caries, trauma, or exposed cementum.[3] The pulp will react to injury via localized inflammatory processes and the formation of a protective, reactive layer of tertiary dentin.[4]

Severe inflammatory reactions can lead to pulpal cell injury, potentially compromising pulpal vitality and survivability. Although the infection activates an immune response, immune cells and molecules are unable to effectively penetrate dentin to remove pathogens due to the narrow apical foramen of the tooth and the hard enamel surrounding the internal structures.[2]

Once pulpal vascularity is dysfunctional, progression to pulpal necrosis and apical pathosis is typical.[2] Pulpal necrosis is the "death of cells or tissues through injury or disease, especially in a localized area of the body."[5] Pulpal necrosis is a continuum, as partial necrosis can exist before complete necrosis occurs.

The now infected and necrotic root canal system is a habitat that allows for the growth and establishment of a mixed, predominately anaerobic flora, which mainly grows in sessile biofilms and aggregates or co-aggregates.[6] The microbial invaders or their by-products can advance into the periapex of the root. In response, the host mounts a defensive mechanism through various cells, intracellular mediators, and humoral antibodies.[7]

As the invading oral microflora and the immune response clash, the periapical tissues surrounding the tooth's root, such as the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, can be destroyed. This destruction causes periodontal lesions, which may vary in clinical manifestations.[7]

Thus, we can describe apical periodontitis as an inflammatory disease due to the dynamic interaction between oral bacterial invaders and the body's defensive mechanism at the tooth apex.[7] Despite the complex host defensive system, the causative organisms are well-entrenched in the intricate and delicate root canal system, which is beyond the reach of the host immune response.[8] Therefore, apical periodontitis is not self-healing, and resolution of the disease can only result through surgical or non-surgical endodontic therapy or removal of the tooth in question.[8]

Epidemiology

Around 52% of the worldwide adult population has had at least one tooth affected by apical periodontitis (AP).[9] There is a slightly higher prevalence of AP among individuals in developing countries compared to developed ones, likely attributed to access to care and patient education. The frequency of AP was also greater in individuals with systemic diseases.

Patients with diabetes typically have a higher frequency of tooth loss and endodontically treated teeth due to increased chronic inflammation, reduced tissue repair capacity, decreased response to infection, and delayed wound healing.[10]

Patients who previously received endodontic therapy also had a higher incidence of AP than those with non-endodontically treated teeth.[9]

Pathophysiology

Apical periodontitis results from the encounter between microbial organisms and the host defense system.[7] Several factors influence the virulence and pathogenicity of the invading microbes, including the interactions with other microorganisms present in the root canal, the ability to evade and interfere with host cellular defenses, the release of bacterial modulins, and finally, their ability to synthesize enzymes that damage host tissues.[7]

As previously stated, the host response includes various cells, mediators, effector molecules, and antibodies. The cellular elements include polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and plasma cells.

Polymorphonuclear leukocytes play a significant role in the host response, as they secrete cytoplastic granules with enzymatic properties. Although the primary responsibility of PMNs is to protect the host, they can cause structural damage to tissue cells and extracellular matrices.[11] Thus, we can see how the accumulation of PMNs plays a significant role in the destruction of periapical tissues during the acute phase of AP.[7][11] Other host cells that play crucial roles are lymphocytes, macrophages, and osteoclasts.

History and Physical

A complete medical history should be taken at every patient encounter, including medications and allergies, as antibiotics aid in treating some apical diseases by decreasing the associated complex bacterial load.[12] In addition, a history of the patient's symptoms can help the clinician determine the origin of the patient's chief complaint. Some lesions may be symptomatic, while others may be accidental findings during routine dental care and treatment. The clinician must determine whether the lesions are odontogenic or non-odontogenic in origin through a thorough clinical and radiographic examination.

Apical periodontitis can be classified according to its presentation into 1) initial apical periodontitis (also known as acute apical periodontitis) and 2) chronic apical periodontitis.

Initial Apical Periodontitis

Initial apical periodontitis can result from both infectious or aseptic inflammation.[7] It can be caused by microbial invasion into the periapical tissues, trauma, instrumentation injury, endodontic materials, and chemical irritation.[7]

Symptoms at this stage include pain, tenderness on pressure, difficulty eating in the area, and sensation of tooth elevation.[7][13] Clinicians will rely on patients reporting their signs and symptoms for diagnosis. Radiographic changes in the periapical tissues are rarely observed in the initial stages of the condition because the inflammation is limited to the periodontal ligament, and the host response has not had enough time for substantial tissue changes to occur.[7] Therefore, bone, cementum, and dentine integrity have not yet been disrupted.[7] It is noteworthy that the lesion may resolve, the apical tissues may restore when the irritant is non-infectious, and no further irritation occurs.[14]

The early stage of apical periodontitis is an inflammatory process where neutrophils are extravasated to the area through chemotaxis. The neutrophils attack and kill the offending microorganisms and release leukotrienes and prostaglandins, which attract more neutrophils and macrophages to the site.[7]

Activated macrophages release other cytokines that intensify the vascular response and osteoclastic bone resorption. At this point, the acute phase may take different courses: healing or worsening the infection. When root canal therapy is initiated, and the offending microbes are removed from the root canal system, the lesion may resolve, and the periapical tissues will remain unchanged radiographically.[14] Conversely, if the infection is not resolved, it will become chronic, receiving the name of chronic apical periodontitis.[8] These lesions may spread through the bone to other fascial spaces causing abscesses or opening to the exterior, creating a fistula.

Chronic Apical Periodontitis

If the oral microbes and their by-products remain after the initial host response, the lesion may turn from a neutrophil-dominated lesion to a macrophage-dominated lesion encapsulated in connective tissue.[7] Unlike their acute counterpart, chronic lesions are often asymptomatic. Due to the destruction of the periodontal ligament and the alveolar bone, radiographic changes become evident.

In the chronic phase, activated T- cells produce a variety of cytokines that down-regulate and suppress the osteoclastic activity (reducing bone resorption) and increase the production of connective tissue growth factor (TGF-beta).[7] The reduction in bone resorption and the regeneration of connective tissue structure explains why chronic lesions can remain dormant and asymptomatic for extended periods without significant radiographic changes. Histopathologically, chronic apical periodontitis lesions are encapsulated with fibrous tissue, and some may be epithelized.[7]

Evaluation

When evaluating a painful tooth, attempting to reproduce the patient's symptoms is essential before beginning any treatment. Reproducing the patient's symptoms helps formulate the correct diagnosis and ensures that the treatment matches the appropriate diagnosis.

Pulp testing typically consists of various measures, including evaluating tooth vitality, sensibility, and sensitivity.[15] Vitality testing assesses the pulp blood supply. Sensibility measures sensory response, which includes the standard pulp tests via electric and thermal stimulation. The dental pulp is considered normal when its response is within normal limits and does not linger (the response lasts less than 30 seconds). Pulpitis is an exaggerated response that produces pain. Pulpitis can be reversible or irreversible, depending on the severity of the pain and how long the pain lingers after removing the stimulus (longer than 30 seconds).[16] When no response is elicited, the pulp is diagnosed necrotic.[15]

In acute apical periodontitis, the dental pulp may remain vital or have lost vitality and become necrotic. The tooth will be tender and painful on percussion. Radiographic examination is usually unremarkable, or there may be just a small thickening of the periodontal ligament space and a slight loss of lamina dura in the periapex. By contrast, in chronic apical periodontitis, the pulp is necrotic and infected; therefore, pulp sensibility tests will not elicit a response. The tooth is not tender to palpation, pressure, or percussion, but it may have some mobility and feel different. The finding of a radiolucent lesion in the periapex on x-ray marks the stage of chronic apical periodontitis.

Treatment / Management

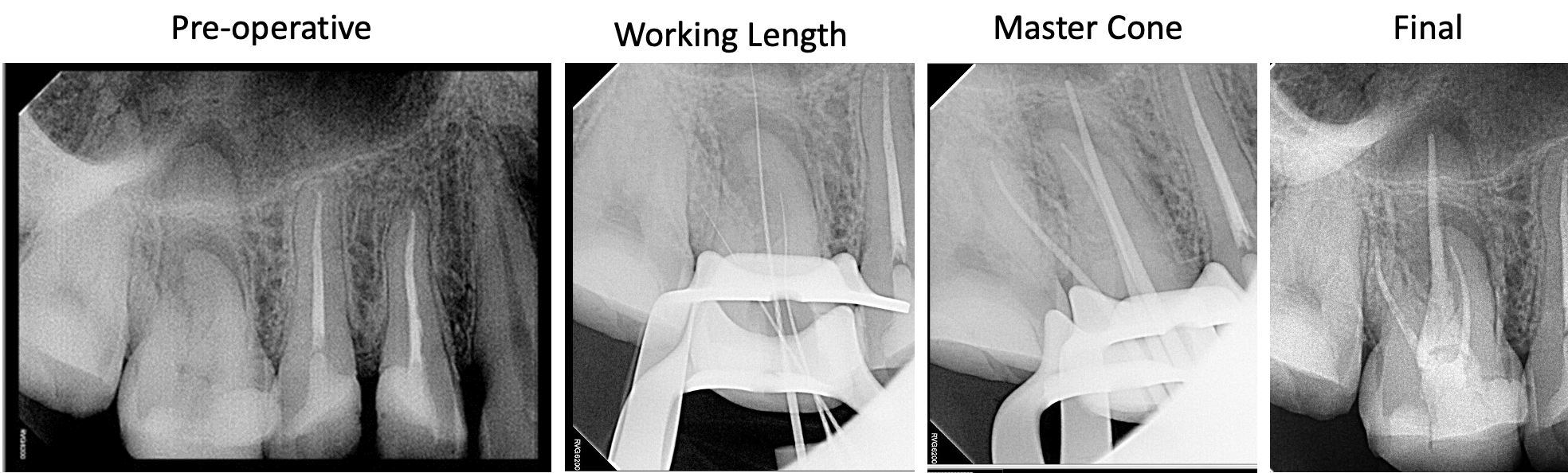

Treatment aims to remove or significantly reduce the intracanal microbes and prevent re-infection by placing a root canal filling.[17] When endodontic treatment is adequately done, the periapical lesion heals with hard tissue regeneration, which is evident in follow-up radiographs through a reduction in the radiolucency's size.[17] Apical periodontitis lesions are expected to heal completely within six months to two years, but some may persist.[18]

Follow-up appointments are essential to assess the progression and efficacy of treatment. Further management is indicated when a periapical radiolucency remains unchanged after one year of root canal treatment, when it has increased in size, or if it appears in an endodontic-treated tooth without a prior apical disease.[18]

A periapical radiolucency often persists when the root canal treatment cannot control the infection because some clinical steps were not adequately followed, such as insufficient aseptic control, poor instrumentation, inadequate access cavity design, unreached canals, and restoration leakage.[17]

However, some periapical lesions may persist despite following the most strict and careful clinical protocol due to the complex anatomy of the root canal system.[17] In cases of post-treatment disease, non-surgical endodontic retreatment or periradicular surgery are treatment alternatives to save the tooth.[18]

Antibiotic use is generally contraindicated, except in cases with rapid onset or systemic involvement.[12] These cases include lymphadenopathy, malaise, a sudden onset of symptoms in less than 24 hours, and a fever over 38 degrees Celsius. Despite not being used in every case, antibiotics may be necessary for immunocompromised patients.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

Apical Radiolucencies

- Periapical granuloma

- Periapical cyst

- Lateral periodontal cyst

- Dentigerous cysts

- Odontogenic keratocysts

- Ameloblastomas

Apical Radiopacities

- Hypercementosis

- Cemento-osseous dysplasia

- Idiopathic osteosclerosis

Apical radiopacities are likely not associated with endodontic infection directly but are commonly found on routine radiographic evaluation. Radiopacities are generally benign.

Prognosis

Long-term outcomes have shown high success rates of 2 to 13 years.[19] Treatment is predictable when using modern endodontic microsurgery techniques. The highest success rates are associated with initial endodontic treatment. Studies show success rates decrease with endodontic retreatment and periapical surgery.[20][21]

Non-surgical endodontic therapy has a success rate of 85 to 94%, depending on the presence of a periapical radiolucency. Non-surgical endodontic retreatment has a success rate of 74 to 82%, and periapical surgery has a success rate of 60 to 91%.[20]

With microscopes and delicate instruments, periapical surgeries remove the apical portion of the root and fill the root in an apico-coronal direction, known as a root-end resection and root-end fill. The dentist should assess postoperative healing radiographically at 12 months post-treatment. 88% of lesions show evidence of recovery at 12 months postoperatively, compared to only 50% when reevaluated at six months. [20]

It is also important to note the lesion's size, shape, and presentation clinically and radiographically. This practice will provide comparative information for any follow-up visits.

Complications

Some patients may experience pain and swelling after endodontic treatment. This is commonly known as a flare-up.[22] Flare-ups can occur within hours or days following treatment. The frequency of flare-ups is between 1.4% and 16%.[22] Etiologies that lead to clinical flare-ups include microbial, mechanical, and chemical irritants.

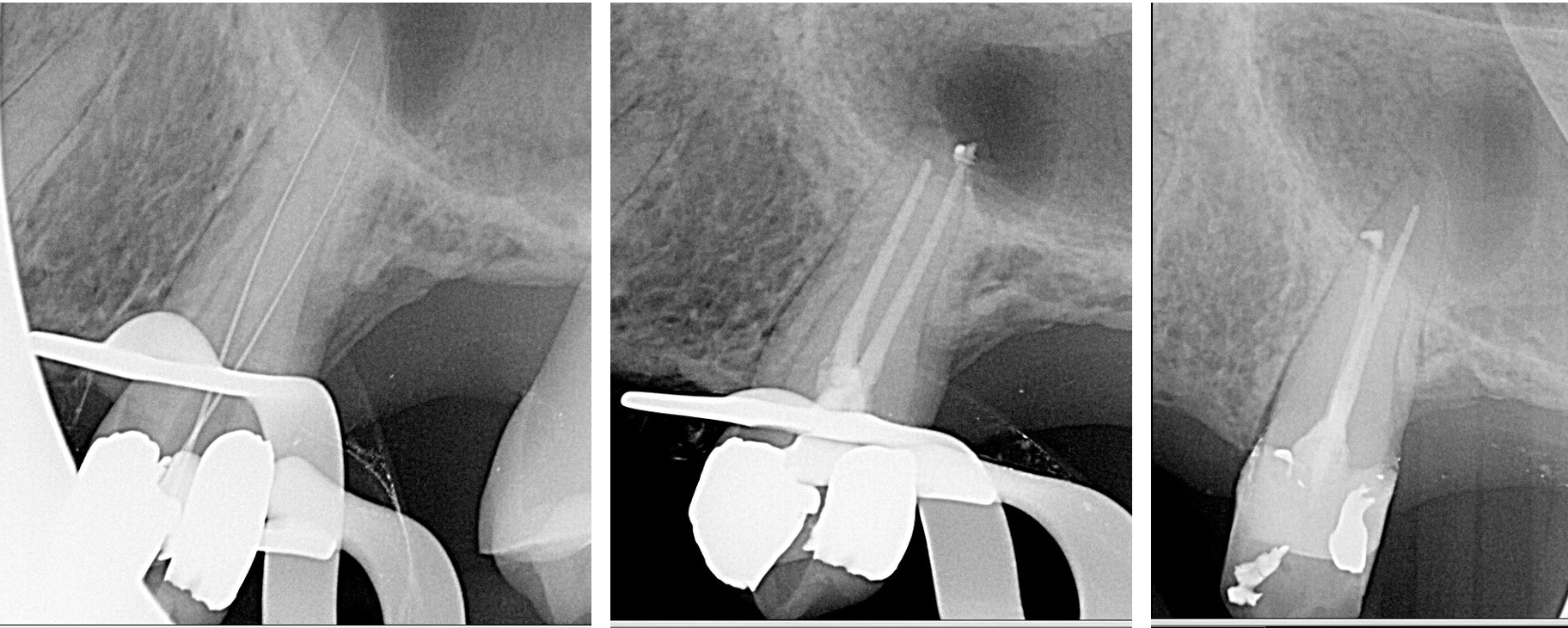

A principal cause of microbial flare-ups is the apical extrusion of pulpal debris.[23] When debris is extruded through over-instrumentation and incorrect working lengths, the host's response increases inflammation to combat the extruded organisms. This acute inflammatory reaction increases vascular permeability, leading to edema. With increased hydrostatic pressure, nerve endings become compressed and generate pain. In addition, incomplete chemo-mechanical canal preparation during non-surgical endodontic therapy can cause remaining bacteria to multiply and express virulence factors, resulting in further damage to the periapical tissues.[23]

Mechanical flare-ups occur due to over-instrumentation and extrusion of filling materials during obturation.[24] Over-instrumentation leads to excessive opening of the apical third of the root. To ensure proper cleaning and shaping and to prevent the destruction of the apical constriction, it is essential to have the correct working length. Chemical irritation caused by extrusion into the periapical region may also lead to increased inflammation.[22]

Odontogenic infections are the leading cause of abscesses of the deep fascial planes in the head and neck.[25] Once the periapical infection spreads beyond the cortical plates of the mandible or maxilla, the bacteria can spread into other spaces as they will likely follow the path of least resistance through soft tissue. Severe infections can lead to Ludwig Angina, a life-threatening condition. Ludwig Angina is a deep space infection that rapidly progresses, threatens the airway and vital structures, and is characterized by the involvement of the submental space and bilateral submandibular and sublingual spaces. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons should provide the management and care for these emergencies.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Vital teeth show a higher incidence of postoperative pain when compared to necrotic pulps and retreated teeth, 64%, 38%, and 49%, respectively.[26] Patients with symptomatic apical periodontitis also show an increase in predicting postoperative pain. A dentist can usually manage postoperative pain with over-the-counter medications, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Based on a study by Stamos et al., there is no statistical difference between ibuprofen 600 mg versus a combination of 650 mg acetaminophen/ibuprofen 600 mg as prescribed every 6 hours for symptomatic patients.[26]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Regular and comprehensive dental examinations are critical in the early identification of any infectious or carious process throughout the dentition. Therefore, dentists must emphasize to their patients how crucial frequent, comprehensive dental examinations are. In addition, patients who have received endodontic therapy in the past should be routinely evaluated clinically and radiographically to ensure the healing of their infections is progressing normally.

The dentist must examine for any new or worsening symptoms and identify the potential risk of reinfection of the tooth. Patients should also be advised that any posterior tooth that receives endodontic therapy will require a cuspal coverage restoration to support the integrity of the treated tooth.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

It is the responsibility of the interprofessional dental team to work together to treat endodontic infections. Dental hygienists often serve as the first line of evaluation during dental prophylaxis treatment and should report to the dentist any significant concerns from the patient. Dentists should also be prudent in endodontic case selection and management. For example, if a patient requires endodontic therapy, and the recommended treatment is severely complex, or the dental practitioner feels complications could arise, the dentist should refer the patient to an endodontist to ensure proper patient management. In addition, if other healthcare professionals note any intra- or extra-oral swelling, a referral or consultation with a dental professional to evaluate for potential endodontic infections would be appropriate. Ensuring proper continuity of care will result in optimal care coordination between health professionals to improve patient outcomes and patient safety and enhance team performance.