Continuing Education Activity

Non-odontogenic cysts arise from tissue not involved in tooth formation. While uncommon, these lesions can be encountered by many health professionals. This activity outlines and reviews the evaluation and management of non-odontogenic cysts and highlights the role of the interdisciplinary team in evaluating and treating patients with these conditions.

Objectives:

- Describe the most common non-odontogenic cysts.

- Identify the etiology of non-odontogenic cysts.

- Review possible treatment modalities for non-odontogenic cysts.

- Outline an interprofessional approach to the evaluation, management, and follow-up of non-odontogenic cysts.

Introduction

Non-odontogenic cysts are usually discovered during a routine examination. These lesions arise from the non-odontogenic (non-tooth forming) tissue. By definition, the cysts are lined by epithelium. Cysts within the oral cavity vary in their clinical appearance, incidence, histology, behavior, and management. The clinical features, etiology, and treatment modalities for the following lesions will be discussed in this activity: nasopalatine duct cyst, nasolabial cyst, palatal cyst of the neonate, oral lymphoepithelial cyst, and epidermoid cyst.

Etiology

Nasopalatine duct cysts are developmental in origin, arising from epithelial remnants of the nasopalatine duct.[1] The development of this cyst can be attributed to several etiologic factors, such as infection, trauma, or mucous retention.

Nasolabial cysts are developmental in origin. There are currently two hypotheses that exist for the pathogenesis of these cysts. The first states that the cyst is formed from retained epithelial cells within the mesenchyme after the fusion of the nasal processes. The second proposes that the cyst arises from epithelial remnants of the nasolacrimal duct in the area of the nasal process and maxillary prominence. Both theories remain to be determined.[2]

Palatal cysts of the neonate, also known as Epstein pearls or Bohn’s nodules, result from keratin entrapment within the palate, resulting in cystic lesion formation.[3] Epstein pearls occur along the median palate raphe, and Bohn nodules are scattered over the hard palate, often at the junction of the soft palate.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts have several theories regarding pathogenesis; however, the most accepted theory involves the association with oral lymphoid tissue (Waldyer ring) and the entrapment and/or accumulation of desquamated epithelial cells within a dilated crypt.[4]

Epidermoid cysts are developmental in origin and are considered inclusion cysts that are derived from the ectoderm. These cysts can also be acquired by trauma resulting from the forced displacement of epithelial tissue into deeper tissue layers forming a cystic cavity.[5]

Epidemiology

Nasopalatine duct cysts are the most common non-odontogenic cyst found within the anterior maxilla.[6] There is a 3 to 1 predilection for males; however, there is no significant correlation between the size of these cysts and the patient’s gender.[7] The mean age of patients presenting with nasopalatine duct cysts is 47 years of age.[8]

Nasolabial cysts are relatively rare, accounting for only 0.7% of all maxillofacial cysts.[9] These cysts are typically found in female adults between the fourth and fifth decade of life. The mean age of patients presenting with nasolabial cysts is 51 years of age.[8]

Palatal cysts of the neonate are very common, occurring in 60% to 85% of newborn infants.[3] No gender predilection has been identified.[10] A study completed by Moosavi and Hosseini discovered that babies born at term had a higher incidence of palatal cysts compared to those born post-term.[11]

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts are relatively rare and have no gender predilection.[12] These lesions are usually associated with Waldyer’s ring, which includes the palatine and lingual tonsils and the pharyngeal adenoids. The incidence rate is 1.2% to 7%.[13] The mean age of patients presenting with oral lymphoepithelial cysts is 44 years of age.[8]

Epidermoid cysts are rare and have a predilection for males.[5][14] The mean age of patients presenting with intraoral epidermoid cysts is 28 years of age.[8]

Pathophysiology

Nasopalatine duct cysts arise from epithelial remnants of the nasopalatine duct, which can undergo activation by trauma, infection, or spontaneously.[6] These lesions are developmental or reactive in origin.

Nasolabial cyst's pathogenesis is unclear; however, it is suggested that the epithelium in the nasolacrimal duct undergoes spontaneous activation and subsequent cyst formation.[9] These lesions will spontaneously appear and grow in size, commonly unnoticed by patients until symptoms arise or they become an esthetic concern.

Palatal cysts of the newborn arise from entrapped epithelium during the fusion of the palatal processes or trapped minor salivary glands.[3] As these shelf-like processes close at 10 to 11 weeks in utero, clefts of the epithelium may persist, creating cyst-like cavities that fill with keratin and manifest intraorally. Epstein pearls are located along the median palate raphe, while Bohn’s nodules are scattered near the junction of the hard and soft palate.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts arise from either entrapped epithelium in the area of Waldyer’s ring or from obstructions in minor salivary gland ducts.[15] If salivary gland ducts become obstructed, the gland will continue to produce secretions and build up, forming an inflamed cyst-like lesion.

Epidermoid cysts arise from epidermal inclusions. In comparison to the dermoid cyst, the epidermoid cyst does not demonstrate any skin adnexa, like sebaceous glands or hair follicles.[16] These epidermoid inclusions can form cystic cavities over time leading to the development of an epidermoid cyst.

Histopathology

Nasopalatine duct cysts present histologically as a cystic lining of flattened stratified squamous epithelium approximately 2 or 3 cell layers thick.[6]

Nasolabial cysts present histologically as a cystic lining of epithelium, ranging from stratified squamous epithelium to ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium.[17] Scattered mucous or goblet cells are typical inclusions.

Palatal cysts of the newborn present histologically as a keratin-filled cystic lumen lined by stratified squamous epithelium.[3]

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts present as a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium surrounded by lymphoid tissue. The cyst appears encapsulated by the surrounding lymphoid tissue.[15]

Epidermoid cysts present histologically with a cystic wall of stratified squamous epithelium without skin adnexa present. The cystic lumen typically presents with abundant keratin flakes.[18]

History and Physical

Nasopalatine duct cysts present as well-circumscribed radiolucencies noted in the anterior maxilla. Oftentimes, the nasal spine is superimposed on the image, giving the lesion a “heart-shaped” appearance. Clinically, these lesions can present as painless, firm swellings on the anterior hard palate crossing the midline with or without drainage.[6]

Nasolabial cysts present as an asymptomatic swelling approximating the nasolabial region of the midface. They range from 1 to 5 centimeters in diameter.[2][19] Palpation of these lesions reveals a soft and fluctuant consistency. Patients will typically report symptoms of nasal blockage or possible esthetic concerns.[2]

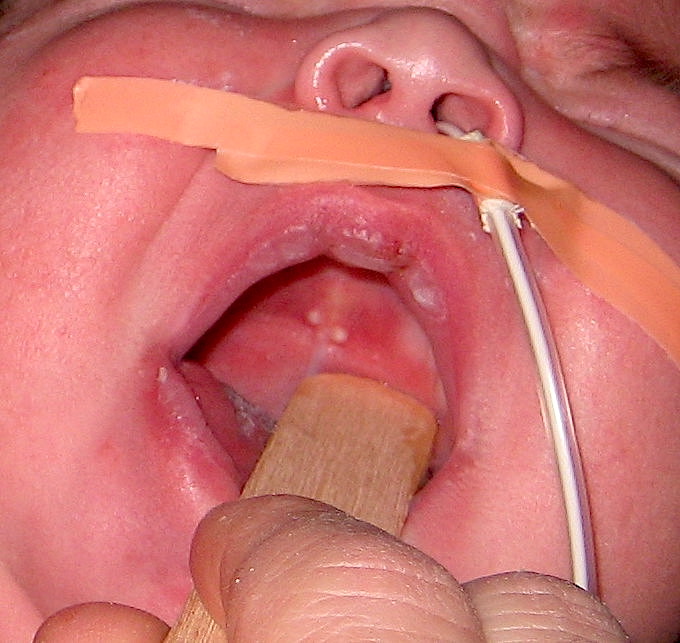

Palatal cysts of the neonate are small, white to yellow nodules adjacent to the palatal midline.[20] These lesions are firm to the touch and range from one to several millimeters in size. They can appear as a solitary cyst or small outcroppings of several lesions.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts present as yellowish-white nodules with relatively smooth surfaces. Most lesions present on the ventral surface or lateral borders of the tongue or the floor of the mouth but can be discovered on any oral mucosal surface associated with the Waldyer ring.[15]

Epidermoid cysts present most commonly on the floor of the mouth as an asymptomatic slow-growing mass. They are typically not discovered until becoming large in size.[13][21] These lesions are firm and fluctuant upon palpation.

Evaluation

Nasopalatine duct cysts present histologically with an epithelial-lined cyst wall surrounded by fibrovascular connective tissue, oftentimes with minor salivary glands as incidental findings.[22] Vitality testing must be performed on teeth associated with the lesion to rule out an odontogenic source, such as a periapical cyst or granuloma. Teeth associated with a nasopalatine duct cyst will test vital.

Nasolabial cysts present histologically with pseudostratified columnar epithelium with occasional stratified squamous epithelium.[23] The diagnosis is reached by correlating the histopathological with clinical information/presentation.[24]

Palatal cysts of the neonate are diagnosed clinically and therefore require no additional tests.[3]

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts present histologically as a cyst lined by stratified squamous epithelium surrounded by lymphoid tissue.[25] Nuclear atypia is generally not seen.[26]

Epidermoid cysts present histologically as keratinized stratified squamous epithelium-lined cysts without dermal appendages in the underlying fibrous connective tissue. With more diagnostic imaging modalities, such as a CT scan, lesions may appear as well-circumscribed, unilocular, low-density masses.[13]

Treatment / Management

Nasopalatine duct cysts are best treated by surgical resection. After removal, it is important to monitor patients both clinically and radiographically to determine if the lesion has completely resolved. Recurrence is rare.[27]

Nasolabial cysts are typically removed via conservative surgical excision.[2] Recurrence is rare.

Palatal cysts of the neonate are self-limiting and will rupture with time.[20] Parents of infants presenting with these lesions should be reassured that the lesions will resolve on their own. Recurrence is rare.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts can be removed via conservative surgical excision.[26] Once surgically removed, recurrence is not expected.

Epidermoid cysts are typically removed via conservative surgical enucleation.[21] Recurrence is rare.

Differential Diagnosis

Nasopalatine Duct Cysts

- Any odontogenic cyst (lateral periodontal cyst and periapical cyst/granuloma)

- Enlarged incisive fossa

- Central giant cell granuloma

Nasolabial Cyst

- Radicular cyst

- Periapical abscess

- Nasopalatine duct cyst

- Benign mesenchymal tumors

- Minor salivary gland tumors

Palatal Cysts of the Newborn

- Congenital epulis

- Dental lamina cysts

- Natal tooth

Oral Lymphoepithelial Cyst

- Branchial cleft cyst

- Lipoma

- Mucocele

- Sialolithiasis

Epidermoid Cyst

- Lipoma

- Dermoid cyst

- Oral lymphoepithelial cyst

- Benign mesenchymal tumors

Prognosis

Nasopalatine duct cysts have an excellent prognosis with rare recurrence.[22] The biopsy usually reveals adequate treatment (complete excision).

Nasolabial cysts have an excellent prognosis as complete surgical excision is curative.[2]

Palatal cysts of the newborn have an excellent prognosis as they self-resolve in weeks to months.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts have an excellent prognosis. They are benign, and to date, there have been no recurrences reported in the literature.[12]

Epidermoid cysts have a good prognosis with low to rare incidences of recurrence.[28]

Complications

Nasopalatine duct cysts can be expansile in nature and may result in drainage intraorally. These lesions can be caused by mucous retention and inadequate drainage, leading to pain or pressure symptoms as the lesion expands.[29] Most lesions are typically asymptomatic and non-specific and can be easily overlooked/missed on routine evaluations.

Nasolabial cysts may present clinically as both non-odontogenic and odontogenic lesions. Thus the histological analysis is key to the diagnosis.

Palatal cysts of the newborn spontaneously rupture and present with no complications.[3]

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts typically do not present with complications once removed. There is no recurrence after excision.

Epidermoid cysts that become larger in size have the potential to result in complications, such as difficulty with breathing and/or speech.[30] Patients are typically unaware of these lesions until they become larger in size and/or present with symptoms.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Nasopalatine duct cysts are developmental in origin, and consequently, there are no preventative measures. Patients should be informed of any radiographic findings and counseled on having the lesion biopsied to rule out other lesions.

Nasolabial cysts are developmental in origin. Patients should be made aware that recurrence of these lesions is rare.

Palatal cysts of the newborn are developmental in origin. Parents of infants presenting with these lesions should be reassured that the lesions will self-resolve with time.

Oral lymphoepithelial cysts are developmental in origin. Patients should be informed of these lesions and the plan to have them excised.

Epidermoid cysts are mostly developmental in origin. Conservative management and subsequent removal of these lesions typically result in their resolution.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All members of the interprofessional healthcare team may encounter non-odontogenic cysts in the oral cavity. It is important to note that most of these lesions are developmental in origin and have a low, if any, malignant potential. Treatment of these lesions is typically conservative surgical excision or self-monitoring. Lesions that have rapid growth, are fixed, and/or appear atypical should be referred immediately to the appropriate healthcare specialist for evaluation, biopsy, diagnosis, and management.