Introduction

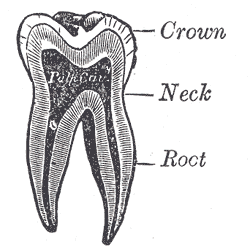

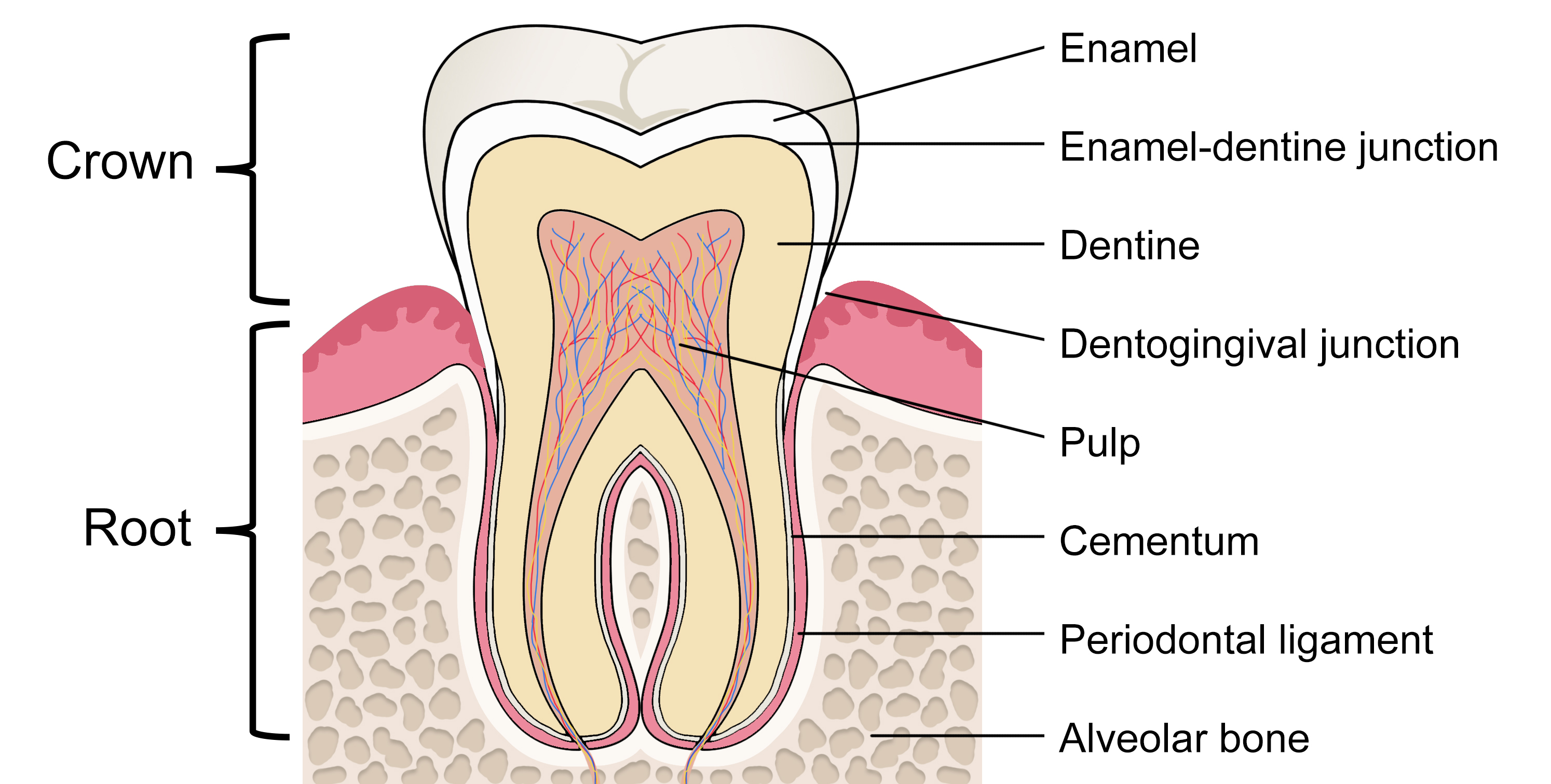

The tooth can be divided into two main parts: the crown and the root. An indentation (cervical line) encircles the tooth marking a distinction between the crown and the root. The crown is the part that emerges from the maxillary or jaw bone, has a hard and translucent surface (enamel); the root anchors the tooth to the alveolar bone and provides blood and nerve supply through the apical foramen.

The enamel is composed mainly of hydroxyapatite, an inorganic substance highly mineralized and aligned in rods to provide maximum protection to the underlying dentin.[1] Mature enamel is acellular; it is non-vital and not sensitive. Enamel cannot regenerate and cannot be replaced. Dentin is produced by specialized cells called odontoblasts that align the matrix inside closely packed tubules; those structures will undergo mineralization, giving structural resistance. The periphery of the dentin is composed of odontoblasts arranged in a picket fence fashion from the underlying pulp and have cellular processes extending into the dentin's tubules. This structure gives sensitivity to the dentin that produces pain when the protective layer of enamel is eroded. In response to physiologic or pathologic stimuli, odontoblasts can upregulate their protein synthetic activity.Pulp is the inner part of the teeth and is composed of loose connective tissue produced by fibroblasts, many small vessels, and nerves. The teeth are anchored to the alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament, composed of fibrous tissue.

Issues of Concern

Enamel is a non-renewable tissue, and enamel preservation is crucial for the dental professional. The physical properties and histology must be considered when treating and counseling patients, and appropriate knowledge of enamel sealants, polishing, and other products is pivotal.

Structure

Enamel is produced by specialized epithelial cells, the ameloblasts.[2] During development, the ameloblasts cover the entire surface of the developing tooth with an amorph matrix, rich in proteins, acellular, and avascular, that is then filled with ribbon-like crystals of carbonate-hydroxyapatite. These crystals are organized in rod and interrod spaces away from the dentin. In the second phase of enamel maturation, ameloblasts form tight junctions and membrane infoldings from the apical ends of the cells, changing the pH from mildly acidic to near-physiologic, allowing the crystallization of the matrix.

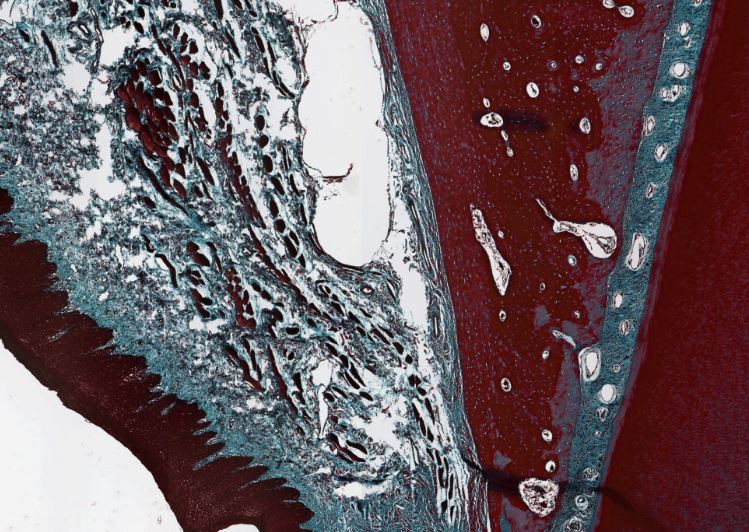

The lines of Retzius are the lines that appear in a histologic section of mature enamel, composed of bands of enamel rods. Strong Retzius lines are formed during ameloblast traumas (such as the birth, which causes the creation of a "neonatal Retzius line") and are characterized by irregular structures of enamel crystals. In its mature state, enamel has an almost total absence of soft organic matrix. Enamel thickness is lower in the cervical region and thicker in masticatory surfaces (incisal ridge and cusps). The enamel on primary teeth has a whiter appearance being in an opaque crystalline form.

Mature enamel is organized in long thin rods of hydroxyapatite crystals. The histological sections cannot examine its structure because the crystals dissolve during decalcification, a procedure that enables cutting the teeth when grossing the specimen. Enamel has a small percentage of proteins: amelogenin, enamelin, and perlecan. The latter is localized in the intercellular spaces of the dental papilla and follicle. The interface between dentin and enamel in the immature developing tooth is composed of enamel epithelium and dental mesenchyme. The enamel covers coronal dentin, while the radicular dentin is covered with cementum.

Cementum is similar to bone in structure and composition, has cementocytes that occupy lacunae, and is composed of an inorganic substance and mineralized organic material. With aging, many cementocytes die, and the cementum loses its regenerative population of cells. A frequent marker of aging is cementicles, small round calcified bodies on the cementum or periodontal ligament. The physical properties of the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ) have been examined, and the tensile cohesive strength of this structure is 51.5 MPa.[3]

Dentin is less hard than enamel but still harder than bone and is composed of weight 70% mineralized material, 20% organic material, and 10% water. The crystals mainly consist of calcium hydroxyapatite Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2 and small percentages of carbonate and fluoride. Dentin protects the pulp and has great tensile strength.

Both dentin and pulp are derived from the dental papilla (tooth germ). Dentin is produced by odontoblasts as predentin, a mesenchymal product composed of collagen fibers, mainly collagen I-III-IV, and phosphoprotein. The latter regulates the mineralization of dentin because it is acidic and highly attractable to calcium. Initially, calcium hydroxyapatite forms as globules within the collagen fibers of the predentin that disperse through the entire matrix. Later, a second mineralization process occurs, with the progressive expansion of the crystals until they almost fuse with each other. This creates the globular dentin and the interglobular dentin, which is less mineralized.

Unlike cartilage, bone, and cementum, the odontoblast does not end entrapped in the dentin matrix; instead, it has long cytoplasmatic extensions that enter the matrix while the body stays on the pulp-dentin interface. Then, the growth of dentin occurs throughout the entire life of the tooth. Like enamel, dentin is avascular. The nutrition comes within the odontoblasts by the dentinal tubules by the transition from the blood vessels in the adjacent pulp. Within each dentinal tubule runs dentinal fluid, the odontoblastic cytoplasmic process, and an afferent axon. The nerve cell associated with the axon is located in the pulp near the odontoblastic cell.Pulp is composed of connective tissue, nerves, and blood vessels. The main functions are support and maintenance of dentin, sensory and nutritive. The pulp can be divided into coronal and radicular; the first is the "crown" of the tooth; the latter is also called "pulp canal" and has an opening near the apex (apical foramen). The apical foramen allows the passage of arteries, veins, lymphatics, and nerves, crucial for the tooth vitality; the opening goes through the cementum into the surrounding periodontal ligament. The foramen is the last part that develops during odontogenesis, is initially located centrally, and becomes smaller and offset during growth.

Accessory canals can be present in different numbers and are located laterally. In odontogenesis, lateral accessory canals form when the root sheath encounters a blood vessel. Two types of nerve fibers are normally present in the root: myelinated nerves (the minority) and unmyelinated nerves (the majority). The nerves are of trigeminal origin, from the mandibular and maxillary branches of the trigeminal nerve. The cell bodies are in the trigeminal ganglion and the odontoblastic layer of the pulp, near the odontoblasts.

The pulp can be anatomically divided into four zones: the odontoblastic layer, mesenchymal zone, cell-rich zone, and the core. The odontoblasts are aligned in the periphery of the pulp and produce secondary or tertiary dentin; the second layer is mostly acellular and has loose connective tissue with nerve fibers and small blood vessels; the adjacent area is more cellular and has a rich vascular and nerve supply, similar to the central core located in the center of the pulp chamber.

Tissue Preparation

Enamel is extremely hard and can only be removed only by rotary cutting instruments or rough files.

Microscopy, Electron

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allows the characterization of the enamel surface.[4] Enamel is composed of prisms, rod sheaths, and cementing interprismatic substances. Prisms are the basic component of enamel and extend through the whole thickness of the outer tooth surface. The prisms have a cylindrical shape in longitudinal sections and a fish-scale pattern in cross-sections. Three different morphological patterns of enamel prisms have been described under SEM analysis.

The first type is a shallow prism, with a round and uniform shape with sharp outlines, located at the same level of the tooth surface. The second type is a well-defined prism with an open concave center and well-defined peripheral outlines at the same surface level as the type 1 prisms. The third type of prisms are ill-defined, irregular shapes and irregular borders, defined as microporosity. The surface enamel of deciduous teeth has a so-called prismless structure with parallel crystallites and no prism boundaries, based on SEM studies.[5] The crystal arrangement creates the discontinuities, known as prism junctions, in an otherwise continuous structure. With maturation, the prism junction acquires a concentrated organic matrix acting as crack stoppers in the adult tooth.

Pathophysiology

Teeth pass through three stages of development: growth, mineralization, and eruption. The growth period is further subdivided into the bud, cap, and bell stages.

Dentin appears more radiolucent than enamel but more radiopaque than pulp, which has the least density. Pulp appears radiolucent (dark) in an X-ray.

Clinical Significance

Knowledge of the basic structure of the teet is paramount to understand pathological processes and the logic behind current medical treatments. Below are some focal points of connection between histology and clinical significance.

The periodontal ligament is the key part of malocclusion correction because it allows small progressive movements used by orthodontic techniques.

Enamel, because of its mineralization, is highly vulnerable to demineralization by acids, and since it cannot be replaced, it is essential to balance the diet, reduce acidic beverages and keep perfect oral hygiene.

Dentin is a sensitive layer, and any alteration of the enamel allows exposure of the dentin to chemical and microbiological elements. Dentin damage is the main reason for dental pain, which is conducted by the tubules to the odontoblast's processes. Invasion of bacteria causes infection of the tubules and may result in dental caries; if the infection is left untreated, there is a subsequent invasion of the dental pulp, compromising the vitality of the tooth.

Developmental remnants are common sources of pathology. The remnants of the dental lamina or rests of Serres are small nests of squamous epithelium under the gum that can proliferate and form cystic structures: gingival cysts. Remnants of Hertwig’s root sheath (rests of Malassez) located in the periodontal membrane (or rarely in the alveolar ridge) can proliferate during bacterial infections and necrosis of the pulp forming the epithelial lining of apical granulomas. These structures are also potential sources of ameloblastomas and odontogenic cysts.

Lateral canals can be present in different numbers in a certain tooth and cause problems during endodontic or root therapies. Radiopaque materials can be used to indicate the number and position of these canals.