Continuing Education Activity

Dilation and curettage (D&C) is one of the most common invasive procedures in the United States. The procedure can be performed on a pregnant or nonpregnant patient and be either diagnostic or therapeutic. Sometimes the circumstances lead to a diagnostic procedure becoming therapeutic. A D&C occurs in 2 steps: dilation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrial cavity. While current recommendations for endometrial sampling in the nonpregnant patient include hysteroscopy with directed endometrial sampling, if necessary resources are unavailable, a simple D&C may be performed to acquire tissue for histologic evaluation. Contraindications to D&C are few, and the overall mortality rate is low. This activity reviews the indications, absolute and relative contraindications, equipment needs, technique, and complications of diagnostic and therapeutic D&C in pregnant and nonpregnant patients. In addition, the role of the healthcare team in improving care for patients undergoing D&C is highlighted.

Objectives:

Select patients who may benefit from preoperative cervical preparation or preoperative antibiotic therapy.

Identify the equipment needs, the role of cervical preparatory agents and pre-operative antibiotics, and the commonly encountered complications of dilation and curettage.

Counsel patients regarding the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the procedure.

Apply effective interprofessional team processes for patients undergoing dilation and curettage in the outpatient or hospital settings.

Introduction

Dilation and curettage (D&C) is one of the most common invasive procedures in the United States. The procedure can be performed on a pregnant or nonpregnant patient and be either diagnostic or therapeutic. Sometimes the circumstances lead to a diagnostic procedure becoming therapeutic. A patient seeking elective termination or management of a missed, incomplete, or inevitable abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy at less than 14 weeks of estimated gestational age could be offered this surgical procedure or medical management. Dilation and evacuation is a similar procedure employed at an estimated gestational age of greater than 14 weeks and is outside this activity's scope.

Approximately 30% of females will have an abortion by age 45 years; most of these occur in an outpatient setting.[1] In 2013, first-trimester aspiration procedures were the most common therapeutic intervention accounting for 74% of abortions.[1] However, more recent data from high-income countries indicate that medical abortions account for approximately half of all abortions, and about 90% of all abortions were completed before 13 weeks.[2]

A D&C may be performed in the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. However, with the advent of aspiration devices for endometrial biopsy and advances in ultrasound technology, the D&C is rarely the first step in the evaluation. D&C may also be used to manage abnormal uterine bleeding refractory to medical therapy.[3]

A D&C occurs in 2 steps: dilation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrial cavity. The first cervical dilators were available in the early 19th century. Recamier is credited with inventing the first curette in 1843, which resembled a small scoop or spoon with a long handle.[4] The instruments used in a D&C have remained essentially unchanged from the original dilators and curettes.

Anatomy and Physiology

A D&C removes tissue from the endometrial cavity. In a nonpregnant patient, the endometrial lining is sampled and sent for pathological evaluation. Current recommendations for endometrial sampling include hysteroscopy with directed endometrial sampling.[5] However, if necessary resources are unavailable, a simple D&C may be performed to acquire tissue for histologic evaluation.

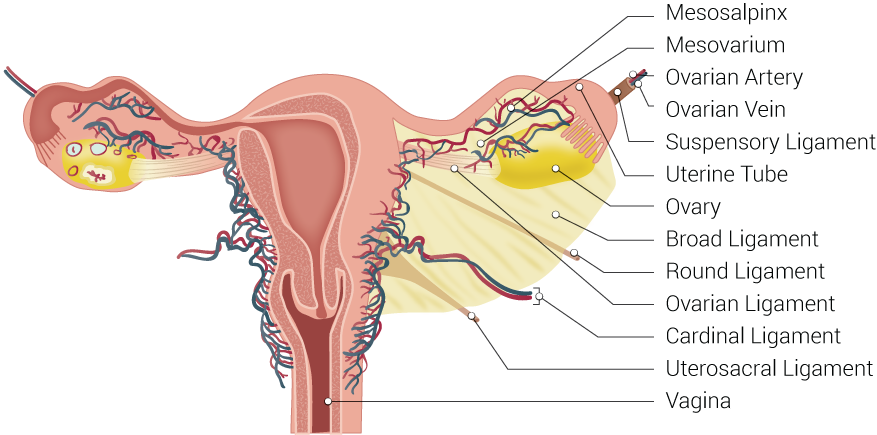

Anatomically the cervix is the lower part of the uterus. The cervix protrudes into the vaginal lumen and is visible on speculum examination. The external cervical os opens into the endocervical canal, which extends proximally to the level of the internal cervical os. The endocervical canal is contiguous with the endometrial cavity. The external and internal cervical ossa are narrower than the endocervical canal; dilation of these openings is often needed to accommodate the instruments used in a D&C.

In the absence of pregnancy, the endometrium has 2 distinct histophysiologic layers; the stratum basalis and the stratum functionalis. The goal of a D&C in a nonpregnant patient is the removal of the stratum functionalis. Removal of this endometrial layer does not affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and does not affect ovulation or future menses.

During pregnancy, the endometrium is highly modified into a specialized tissue, the decidua, divided into 3 layers. The decidua basalis is where the blastocyst implantation occurs, and the basal plate is formed. When performing a D&C on a pregnant patient to remove the products of conception from the endometrial cavity, care must be taken to avoid removing tissue beyond the decidua basalis, as removal of that tissue can predispose to the formation of endometrial adhesions.

Indications

There can be diagnostic and therapeutic indications for a D&C; these indications differ between pregnant and nonpregnant patients.

Indications for a D&C in the pregnant patient include elective termination of pregnancy, early pregnancy failure, evacuation of a molar pregnancy, or suspected retention of products of conception. The pregnant D&C is usually performed with either manual or electric vacuum aspiration. In addition, a D&C may be used to evaluate the chorionic villi in a patient who has a pregnancy of unknown location.

Many diagnostic indications for a D&C outside of pregnancy have been replaced with office-based endometrial biopsy (EMB). D&C and EMB have been shown to reveal similar cancer detection rates; however, there remain clinical scenarios where that is insufficient. Hysteroscopically-directed endometrial sampling followed by sharp curettage is recommended but not required.[5]

A patient's inability to tolerate an EMB or a failure to obtain a tissue sample sufficient for diagnosis would prompt further endometrial sampling; a D&C may be used in this circumstance. Likewise, cervical stenosis, persistent abnormal bleeding, or postmenopausal bleeding after a benign EMB may warrant a D&C. A D&C may be indicated to exclude endometrial cancer in a patient diagnosed with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia via EMB.

Therapeutically a D&C may be used in a nonpregnant patient with excessive uterine bleeding who has failed medical management or become hemodynamically unstable. In this circumstance, the D&C alone is inadequate as a complete evaluation of the uterine disorder but usually provides a temporary reduction in bleeding.[6]

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication to a D&C is the desire to maintain a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

There are relative contraindications that should be contemplated to determine if the procedure should be performed in the outpatient clinical setting or the operating room. For example, depending on your facility, patients with bleeding diatheses or taking anticoagulant medications could potentiate a problem in the outpatient setting.

In general, first-trimester abortions performed on anticoagulated patients are considered safe and incur similar amounts of bleeding compared with patients not on anticoagulants.[7] Temporary discontinuation of these medications must be weighed with the severity of the disease state. Patients with a coagulation factor deficiency should undergo replacement before the procedure.

In the setting of a suspected molar pregnancy, the D&C should be performed in the operating room in order to control anesthesia complications and the potential for severe hemorrhage. A scheduled or elective D&C should be delayed in a patient with an active pelvic infection. However, in the circumstance of a septic abortion or endometritis with possible retained products of conception, the surgeon should proceed with uterine evacuation.

Equipment

Providers need cervical dilators, curettes, and a manual or electric aspiration instrument.

Dilators

The 3 most common types of dilators are steel Pratt dilators, Hank dilators, and Hegar dilators. No trials have compared the safety or efficiency of these different dilator sets.[8]

Pratt dilators have long tapered tips allowing the operator to use the least mechanical force; for this reason, the Pratt dilator is commonly preferred. Pratt dilators are sized from 9 to 79 French. The French unit is the diameter of the dilator in millimeters. Dividing the French unit by 3, a rough estimate of Pi, yields the diameter of the dilator in millimeters.[8]

Hank dilators are structurally similar to Pratt dilators, but they are cuffed. Additionally, the taper from the tip to dilation is sharper than the Pratt dilator. Pratt dilators may increase the risk of uterine perforation; many operators use the cuff to stop the advancement of the dilator at the external cervical os. However, each cervix and uterine cavity is different.

Hegar dilators are short with a blunt end. They are sized in millimeters and increase in size rapidly, necessitating increased mechanical force during dilation. This may increase the risk of uterine perforation. In addition, patients with obesity or a long vaginal lumen may not be ideal candidates for the Hegar dilator, as the dilator may be too short to traverse the entire endocervical canal.

Curettes

Curettes may be metal or plastic. The diagnostic D&C is typically performed using a sharp metal curette (Figure 5). Metal currettes have a long malleable handle with an open teardrop shape at the tip. These curettes are available in various sizes and are measured by the largest diameter at the tip. A toothed curette is sometimes used in postmenopausal patients for aggressive tissue sampling of the endometrium.

Plastic curettes or cannulas are more commonly used in pregnant patients. These cannulas can be straight or curved and rigid or flexible. These cannulas are measured in millimeters; in the first-trimester abortion, a cannula between 7 mm and 12 mm is usually sufficient. The rigid plastic cannulas are slightly more challenging to place, so if the provider uses a Pratt dilator, they will dilate just past the chosen cannula size. For example, if using an 8 mm cannula, maximum dilation of the endocervical canal with a 25-26 Pratt dilator should be sufficient for cannula placement.

Aspirators

Aspirators are either electric or manual vacuum aspirators. The electric suction aspirator produces a negative pressure to quickly and efficiently empty the uterus and decrease bleeding. However, these machines tend to be loud and can increase anxiety in the patient. The manual vacuum aspirator is a handheld device with a large attached syringe to create negative pressure. These can be very effective when used in the office but tend to prolong procedural times as multiple passes may be required.

Personnel

A trained provider with a single assistant is adequate for an electric or manual vacuum aspiration. The assistant may collect the aspiration contents or provide ultrasound guidance should the provider so desire. While a well-trained single provider can accomplish this procedure, all providers must be supervised by a second party due to the nature of the exam.

Anesthesia personnel will be required if the patient requires IV sedation or a general anesthetic.

Preparation

Cervical Preparation

Unlike a D&E, where cervical preparation is recommended, cervical preparation for a D&C need only be considered. The 2 most commonly used cervical preparations are osmotic dilators or chemical ripening agents.

Osmotic dilators, such as laminaria and Dilapan-S, are established, safe, and effective ways to dilate a cervix; both require overnight placement.[9] These agents are placed through the external cervical os into the endocervical canal and absorb moisture from the cervix, slowly expanding and dilating the canal.

Chemical ripening agents are prostaglandin analogs or progesterone antagonists, which soften or prime the cervix.[8] Misoprostol, a prostaglandin analog, is the most common vaginally-administered medication. Misoprostol is a safe and effective form of cervical preparation and can be administered on the same day as the procedure.[9][10] The progesterone antagonist, mifepristone, is as effective as misoprostol; however, its high cost and limited availability prohibit routine use. The Society of Family Planning does not recommend any cervical preparation for first-trimester abortions unless the patient is at an increased risk of complications such as cervical lacerations, inadequate cervical dilation, or uterine perforation.[8] Cervical priming is timely and can have uncomfortable side effects. However, using a cervical priming agent should be considered in later first-trimester abortions performed between 12 and 14 weeks, and in patients for whom cervical dilation may be challenging, such as adolescents or those with a history of cervical conization.

Prevention of Infection

Vaginal preparation with an antiseptic solution is generally performed to reduce the risk of post-abortion infection. There is limited evidence that preparation with chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine is superior to saline alone, but studies are inadequate. There is data to support that vaginal bacterial load is reduced when using the chlorohexidine solution, but this study was not powered to examine clinical outcomes.[11]

Preoperative antibiotics lower the risk of post-abortion infection in pregnant patients but have not been proven in nonpregnant patients. Routine procedures such as endometrial biopsies and hysteroscopy do not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis; therefore is not recommended for the nonpregnant patient undergoing a D&C. Preoperative doxycycline is a safe and effective prophylactic for surgically induced abortions, whether used as a single dose or short perioperative course.[12]

Technique or Treatment

The patient should be placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. Then, a bimanual examination should be performed to assess the uterine size and position.

A bivalve or weighted speculum is placed in the vagina. If local anesthesia is used, then the cervix and lower uterine segment should be injected. Most commonly, 1% lidocaine is adequate. A tenaculum is used to grasp the anterior lip of the cervix and pull towards the introitus with the non-dominant hand. The traction will stabilize the uterus and reduce the cervicouterine angle to decrease the risk of uterine perforation. Routine use of uterine sound for cavity length does not benefit the procedure unless the uterus was not palpable on the initial bimanual examination.

The procedure is initiated by dilating the cervix with the smallest accommodating dilator; the dilator size is then sequentially increased. The dilator must pass through the external and internal os. Providers learn to identify this landmark with the loss of mild resistance under gentle pressure. The dilator should be held using only two fingers of the dominant hand, and force should not be excessive; excessive force may increase the risk of uterine perforation. The extent of dilation will be determined by the amount of tissue to be removed and the size of the chosen curette. After adequate dilation, the metal or plastic curette is inserted through the endocervical canal into the endometrial cavity and gently advanced to the uterine fundus.

Once the curette is appropriately placed at the uterine fundus, manual or electric suction may be applied. The curette is applied to the walls of the uterus and pulled from the fundus to the cervix while staying inside the uterine cavity during suction to limit any cervical damage. Rotate the curette 360 degrees while proceeding with a repetitive vertical pass motion from the fundus to the level of the internal os covering the entire uterine cavity.

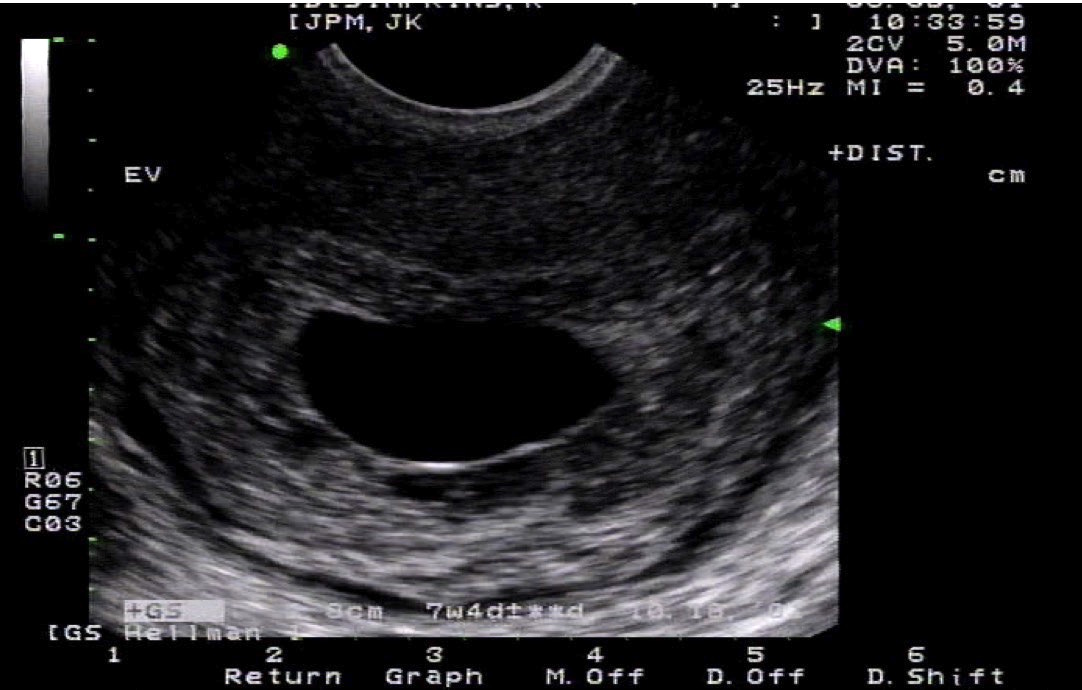

A gritty texture indicates complete removal of the pregnancy or, in nonpregnant procedures, adequate sampling of the endometrium. In the pregnant D&C, there should be limited to no bleeding from the os with total removal of the pregnancy; this indicates the procedure is complete. If a gritty texture is present, but bleeding is seen, consider bimanual massage to treat possible uterine atony, retention of products, or uterine or cervical injury. Ultrasound can directly visualize the uterus while performing the procedure; this is not required. However, the ultrasound may provide a safety measure to prevent injury in patients with an abnormal endometrial cavity or when cervical dilation is difficult.

Complications

The overall mortality rate associated with D&C is low.

The rate is 0.6 per 100,000 legally-performed induced abortions. To put this in perspective, the risk of death associated with childbirth is 14 times this rate. However, the risk of morbidity and mortality increases with increasing gestational age.[13]

Infection, bleeding, cervical lacerations, uterine perforation, and postoperative uterine adhesions are complications of D&C in pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Overall infection rates are low at 1% to 2%, and prophylactic antibiotic use is recommended in pregnant patients.[14] Infection rates are even rarer in nonpregnant patients, and prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended.

Uterine perforation is the most common immediate complication of a D&C in pregnant or nonpregnant patients. Uterine perforation is more likely to occur at the fundus of the uterus, and risk factors for uterine perforation are postpartum hemorrhage, postmenopausal status, nulliparity, and a retroverted uterus.[15] Uterine perforation rates increase in pregnant patients with increasing gestational age.[13] Management of uterine perforation depends on when it occurs during the procedure. If bowel injury is suspected, the procedure may need to be completed under direct visualization using laparoscopy. Laparoscopy should also be performed if there is significant hemorrhage or suspicion of perforation of the lateral uterine wall.

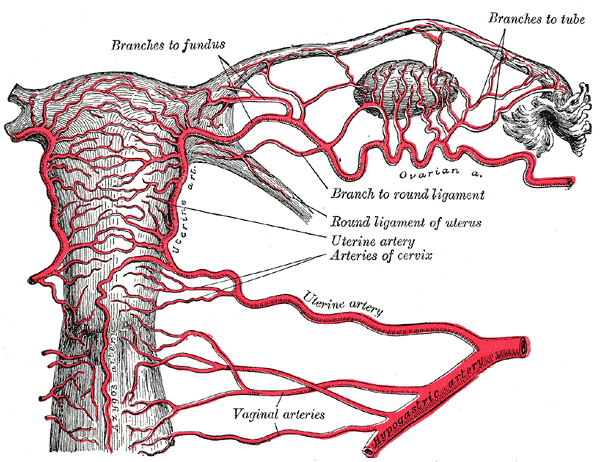

Cervical injury or lacerations to the lip of the cervix typically occur when too much traction is applied to the cervix during dilation or manipulation. Most lacerations can be managed with pressure, silver nitrate, or ferric subsulfate. Occasionally suture ligation is needed. If there is an injury to the endocervical canal, pressure or suture should be attempted first. If there is no response, then balloon tamponade or uterine artery embolization with further evaluation for abdominal or retroperitoneal bleeding should be considered.

Hemorrhage is extremely rare in nonpregnant patients undergoing D&C. The operator should consider uterine perforation or cervical injury as the most likely cause in this setting and manage it appropriately. Hemorrhage is more common in a pregnant patient undergoing D&C, and the risk increases with increasing gestational age and in the postpartum period. Retained products of conception, uterine atony, abnormal placentation, and injury to the cervix or uterus can potentially cause significant hemorrhage in pregnant or postpartum patients undergoing D&C.[13] Management of complications should be specific to the underlying etiology.

Postoperative endometrial adhesions, or Asherman syndrome, is a rare complication of D&C and is most likely to occur in the setting of a septic abortion. These patients may have symptoms of infertility, menstrual cycle changes, or dysmenorrhea. Postoperative endometrial adhesions are definitively diagnosed with hysteroscopy; treatment can be complex depending on the severity of the adhesions.[16]

Clinical Significance

Dilation and curettage (D&C) is a surgical procedure that provides an alternative for pregnant and nonpregnant patients. If the pregnant patient desires an abortion, elective or otherwise, medical and surgical options are available, depending on the estimated gestational age. In this setting, D&C can control bleeding and pain more effectively, providing a more timely therapeutic option than a medical abortion. The results are similar, but the risks and benefits depend on individual patient risks and desires.

The nonpregnant patient can alternatively have a D&C or an EMB with an associated ultrasound to evaluate the endometrial cavity and obtain tissue for histopathological evaluation. The risks and benefits of each approach should be discussed with the patient to determine the most appropriate course of action.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A D&C is an invasive procedure with obvious risks and benefits for pregnant and nonpregnant patients. These must be made transparent in an informed consent process that allows the patient to ask questions about all alternative options and associated issues. Understanding these risks does not diminish the rate of complications but allows the patient and physician to engage in shared decision-making.

Elective abortion is controversial; providers and staff must be aware of potential legal implications and discuss any ethical dilemmas they may face. These discussions should be held well in advance of any patient care, and no one should be asked to participate in any patient encounter if they are uncomfortable with the care being provided. This is where clear and effective interprofessional communication and collaboration in D&C cases are essential to improve patient outcomes and benefit the healthcare team members. [Level 5]